Clotilda (slave ship)

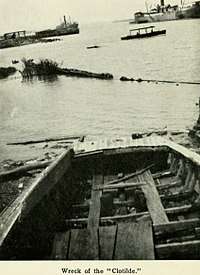

Wreck of the slave ship, Clotilda, photograph from Historic sketches of the South by Emma Langdon Roche, 1914 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Clotilda |

| Fate: | scuttled |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | lumber trade |

| Length: | 86 ft (26 m) |

| Beam: | 23 ft (7.0 m) |

| Sail plan: | Schooner |

The schooner Clotilda (often misspelled Clotilde) was the last known U.S. slave ship to bring captives from Africa to the United States, arriving at Mobile Bay in autumn 1859[1] or July 9, 1860[2][3], with 110-160 slaves.[1] The ship was a two-masted schooner, 86 feet (26 m) long with a beam of 23 ft (7.0 m). The vessel was burned and scuttled soon after at Mobile Bay. The sponsors had arranged to buy slaves in Whydah, Dahomey, on May 15, 1859.[1][2]

Descendants of Cudjo Kazoola Lewis,[1][2] the last survivor of Clotilda and perhaps the oldest slave on the ship, still reside in Africatown, the community they formed on the north side of Mobile, Alabama. After World War II, the neighborhood was integrated into the city. A memorial bust of Lewis was placed there in front of the Union Missionary Baptist Church.[2] The Africatown historic district was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2012.

History

In July 1860, the schooner Clotilda,[4] under the command of Captain William Foster and carrying a cargo of 110 enslaved Africans, arrived in Mobile Bay. [5]

Captain Foster was working for Timothy Meaher, a wealthy Mobile shipyard owner and steamboat captain, who had built Clotilda in 1856 for the lumber trade.[6] Meaher was said to have wagered some "Northern gentlemen" from New England, who likely provided the financing for the illegal venture, that he could successfully smuggle slaves into the US despite the 1807 Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves.

Clotilda was a two-masted schooner, 86 feet (26 m) long with a beam of 23 feet (7.0 m), and a copper-sheathed hull. Meaher had learned that West African tribes were fighting and that the King of Dahomey (now Benin) was willing to sell prisoners taken in warfare as slaves. The King of Dahomey's forces had been raiding communities in the interior, bringing captives to the large slave market at the port of Whydah.[6][7]

Departing on March 4, 1860, Foster sailed from Mobile with a crew of 12, including himself.[8] In addition to supplies, he carried $9,000 in gold for purchase of slaves.[8] He arrived in Whydah on May 15, 1860,[8] where he had the ship outfitted to carry slaves, using materials he had transported.[6] He offered to buy some 125 Africans in Whydah for $100 each.[8] They were primarily Tarkbar people taken in a raid from near Tamale, present-day Ghana.[7] He described meeting an African prince and being taken to the king's court, where he observed some religious practices. According to his journal, Foster was allowed to review 4,000 captives held in a warehouse, from whom he chose 125 for purchase.[8]

As the slaves were being loaded, Foster saw two steamers off the port and ordered the crew to leave immediately, although only 110 slaves had been secured on board. The Clotilda sailed without the last fifteen slaves, in order to avoid capture. After making their way for a time, they saw a man o' war, but were saved when a squall came up and they outran the ship.[8] They reached Abaco lighthouse at the Bahama banks by June 30, on their return to Mobile.[6] As they continued across the Caribbean, they disguised the schooner as a "coaster" (a ship that carried slaves in the coastal trade of domestic slaves along the US coast) by taking down the "squaresail yards and the fore topmast", and avoided interception.[8]

Foster anchored Clotilda on July 9 off Point of Pines in Grand Bay, Mississippi, near the Alabama border. He traveled overland by horse and buggy to Mobile to meet with Meaher. Fearful of criminal charges, Captain Foster brought the schooner into the Port of Mobile at night and had it towed up the Spanish River to the Alabama River at Twelve Mile Island. He transferred the slaves to a river steamboat, then burned Clotilda "to the water's edge" before sinking it.[8] He paid off the crew and told them to return North.[8]

The African slaves were distributed to the financial backers of the Clotilda venture, with Timothy Meaher retaining 30 of the Africans on his property north of Mobile.[1] Cudjo (aka Cudjoe) Lewis was among the 30 held by Meaher. Mobile was in the Deep South and blacks, whether Africans or native-born, were mostly enslaved, occupying the bottom rung of a racial hierarchy. The Africans from Clotilda could not be legally enslaved because they were smuggled in; however, they were treated as chattel.[1] The end of the American Civil War resulted in effective emancipation of the survivors of the Clotilda.

The federal government prosecuted Meaher and Foster in 1861 for violation of the act prohibiting the slave trade, but did not gain a conviction. They had no evidence from the ship nor its manifest. The men were tried in a federal court in Mobile, and the case was dismissed for lack of evidence. Historians believe the case was dropped by the federal government in part because of the outbreak of the American Civil War.

Because Captain Foster reported he burned and sank Clotilda[2] in the delta north of Mobile Bay, archaeological searches have continued into the 21st century for the wreck.[9] Several visible wrecks have been referred to by locals as the slave ship.

The Africans taken by Meaher were held on his plantation. After the war they returned to Magazine Point, and land owned by Meaher on the delta just north of Mobile and on the west bank of the Mobile River. They called their community Africatown.[6] They adopted community rules based on African tribal customs, and chose their leaders. They maintained their language into the 1950s, and kept many cultural traditions for decades. Children born in the community began to learn English, first at church, and then in schools that were founded in the late 19th century. The community grew as workers were attracted to the paper mills built after World War II. In the 20th century, the population reached 12,000. Closing of industries reduced the population, which is about 2,000 in the early 21st century. Since the postwar period, the area was mostly integrated into a neighborhood of Mobile. Some are also in the neighboring town of Prichard, Alabama.

Potential discovery of wreck

On January 24, 2018, reporter Ben Raines claimed to have discovered the wreck of the Clotilda in the lower Mobile-Tensaw Delta, a few miles north of the city of Mobile, Alabama. The discovery was enabled by record low tides caused by the same storm system that caused the January 2018 North American blizzard, when it left parts of the wreckage visible above the mud.[6][10] Based on a preliminary review, a team of archeologists reported, "based on the dimensions of the wreckage and its contents...the remnants were most likely those of the slave ship."[5] People in Africatown have discussed what should be done with the wreckage if it is the Clotilda, and how best to tell their story.

On March 5, 2018, Ben Raines announced that the wreck he had discovered was likely not the Clotilda as the wreckage appeared to be "simply too big, with a significant portion hidden beneath mud and deep water."[11]

Representation in other media

- A local Mobile TV news team produced a program, "AfricaTown, USA", about the settlement and its history.[7]

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr's Finding Your Roots, Season 4, Episode 9 (12 December 2017), showed census data for Mobile, and Captain William Foster's journal from the Clotilda, during a segment explaining the family history of Questlove, a drummer and producer, head of The Roots. His 3x great-grandparents Charles Lewis (b. ca.1820) and his wife Maggie (b. 1830) were among the slaves brought from West Africa on the Clotilda. Gates also discussed an article from The Tarboro Southerner, which reported on July 14, 1860 that 110 Africans had arrived in Mobile on Clotilda. A Pittsburgh Daily Post article of April 15, 1894 recounted the wager that Captain Timothy Meaher made in 1859 that he could smuggle in slaves within two years, and that he accomplished in 1860.[12]

See also

- Wanderer, a slave ship that arrived November 1858 (prior year)

- La Amistad, a slave-carrying cargo ship in the Caribbean taken over by a mutiny

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 David Pilgrim. "Question of the Month: Cudjo Lewis: Last African Slave in the U.S.?" Jim Crow Museum, Ferris University, July 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Black Travel - Soul Of America | Home" (historic sites), Soul of America, 2007, webpage: SoulofAmerica-6678.

- ↑ "AfricaTown, USA". The American Folklife Center: Local Legacies. The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ↑ Ben Raines, "Wreck found by reporter may be last American slave ship, archaeologists say", AL.com, 25 January 2018; accessed 26 January 2018. Quote: "...the ship's license and the captain's journal make clear that Clotilda is correct." (as the name)

- 1 2 Sandra E. Garcia and Matthew Haag, "Descendants' Stories of a Slave Ship Drew Doubts. Now Some See Validation", New York Times, 26 January 2018; accessed 26 January 2018

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Wreck found by reporter may be last American slave ship, archaeologists say". AL.com. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- 1 2 3 "AfricaTown, USA", Local Legacies, 2000, Library of Congress; accessed 28 January 2018

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Last Slaver from U.S. to Africa. A.D. 1860": Capt. William Foster, Journal of Clotilda, 1860, Mobile Public Library Digital Collections; accessed 28 January 2018

- ↑ Sarah Gibbens (Mar 6, 2018). "The Last Ship to Bring Slaves to the U.S. Has Not Been Found". National Geographic Society. Retrieved Mar 12, 2018.

- ↑ Jr, Cleve R. Wootson (2018-01-24). "The last U.S. slave ship was burned to hide its horrors. A storm may have unearthed it". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ↑ "Wreck found in Delta not the Clotilda, the last American slave ship". AL.com. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- ↑ Boyd, Jared (December 18, 2017). "PBS show reveals Questlove descended from last known slave ship, which landed in Alabama". The Birmingham News. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

Further reading

- Diouf, Sylviane Anna. Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Glennon, Robert M. Kudjo; The Last Slave Voyage to America, Fairhope, Alabama: Over the Transom Publishing, 1999.

- Lockett, James D. "The Last Ship That Brought Slaves from Africa to America: The Landing of the Clotilde at Mobile in the Autumn of 1859". The Western Journal of Black Studies, vol. 22, no. 3 (Fall 1998).

- Robertson, Natalie S. The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Making of AfricaTown, USA: Spirit of Our Ancestors. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2008.

- Roche, Emma Langdon. Historic Sketches of the South. New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1914.

- Hurston, Zora Neale. "Barracoon. The Story of the Last 'Black Cargo'", Amistad Press. Harper Collins, 2018.

External links

- "Last Slaver from U.S. to Africa. A.D. 1860": Capt. William Foster, Journal of Clotilda, 1860, Mobile Public Library Digital Collections

- "Why was it significant when Clotilde, the last slave ship, was captured?, enotes.com