Ch’orti’ language

| Ch'orti' | |

|---|---|

| Ch'orti' | |

| Native to | Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador |

| Region | Copán |

| Ethnicity | Ch'orti' |

Native speakers | 30,000 (2000)[1] |

|

Mayan

| |

Early form | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

caa |

| Glottolog |

chor1273[2] |

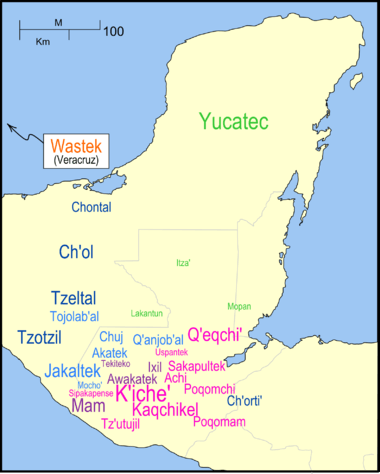

The Ch'orti' language (sometimes also Chorti) is a Mayan language, spoken by the indigenous Maya people who are also known as the Ch'orti' or Ch'orti' Maya. Ch'orti' is a direct descendant of the Classic Maya language in which many of the pre-Columbian inscriptions using the Maya script were written. This Classic Maya language is also attested in a number of inscriptions made in regions whose inhabitants most likely spoke a different Mayan language variant, including the ancestor of Yukatek Maya. Ch'orti' is the modern version of the ancient Mayan language Ch'olan (which was actively used and most popular between the years of A.D 250 and 850).[3]

Relationship to other Mayan languages

Ch’orti’ can be called a living “Rosetta Stone” of Mayan Languages. Ch’orti’ language is an important factor to comprehend the contents of Maya hieroglyphic writings, some of which are not yet fully understood. Over several years, many linguists and anthropologists expected to realize the Ch’orti’ culture and language by studying its words and expressions.[4] Ch'orti' is spoken mainly in and around Jocotán and Camotán, Chiquimula department, Guatemala, as well as adjacent areas of parts of western Honduras near the Copan Ruins.[5] Because the classic Mayan language was ancestral to the modern Ch'orti, Ch'orti can be used to decipher the ancient language. For example, it was discovered that the Mayan language had distinct grammatical patterns, such as a consonant/vowel syllable aspect. Researchers realized that the ancient language was based more on phonetics than previously thought.[6]

The name Chorti' (with unglottalized <ch>) means 'language of the corn farmers' which references to the traditional agricultural activity of the Ch'orti' families. The politicized spelling Ch'orti' was introduced later in an attempt to lessen associations between Ch'orti' speakers and stereotypical professions.

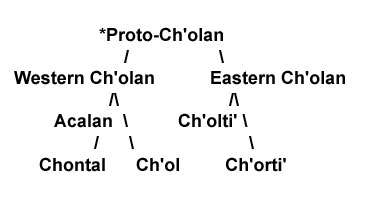

Ch'orti' language is one of the three modern descendants of Ch’olan language which is a sub-group of Mayan languages. Other two modern descendants are Ch’ontal and Ch’ol.[7] These three descendants are still spoken by people. Ch’orti’ language and Ch’olti language are two sub-branches belong to the Eastern Ch’olan. And Ch’olti language is already extinct today.

Actually there are some debates among the scholars how the Ch’olan language should be classified. John Robertson considered the direct ancestor of colonial Ch'olti' is the language of the hieroglyphs. The language of the hieroglyphs is realized as 'Classic Ch'olti'an' by John Robertson, David Stuart, and Stephen Houston. And then the language of the hieroglyphs in turn becomes the ancestor of Ch’orti’.The relationship shows as the chart below.[8]

Phonology and orthography

The Ch'orti' have their own standard way of writing their language. However, the inaccurate ways to represent phoneme lead to some variations among all of the publications recently.[9][10]

Consonants

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiceless | p [p] | t [t] | k [k] | ' [ʔ] | |

| ejective | t' [tʼ] | k' [kʼ] | ||||

| voiced | b [b] | d [d] | g [ɡ] | |||

| implosive | b' [ɓ] | |||||

| Fricative | s [s] | x [ʃ] | j [x] | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | tz [ts] | ch [tʃ] | |||

| ejective | tz' [tsʼ] | ch' [tʃʼ] | ||||

| Nasal | m [m] | n [n] | ||||

| Trill | r [r] | |||||

| Approximant | l [l] | y [j] | w [w] | |||

Ch'orti' 's consonants include glottal stop ', b, b', ch, ch', d, g, j, k, k', l, m, n, p, r, s, t, t', tz, tz', w, x, y.

Both /b/ and /d/ rarely occur in native vocabulary. Instead, they usually appear in Spanish words. The <j> is a voiceless velar fricative. The <x> is a voiceless palatal fricative. The <w> and <y> are semivowels.

The ordering of terms would be that the consonants follows after the non glottal versions. Besides, words with rearticulated root vowels follow after their corresponding short vowels.

Therefore, the order of presentation will be as follows: a, a', b, b', ch, ch', d, e, e', g, i, i', j, k, k', l, m, n, o, o', p, r, s, t, t', tz, tz', u, u', w, x, y.

Vowels

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Open | a | |

The vowels consist of a, e, i, o, and u.[10]

Word order

The aspectual system of Ch'orti' language changed to a tripartite pronominal system which comes with different morphemes used for the subject of transitive verbs, the object of transitive verbs and the subject of intransitive completive verbs, and a third set of pronouns only used for the subject of incompletive intransitive verbs.[11]

Ch’orti’ tripartite pronominal system (data from Hull 2005)

Transitive

| e | sitz’ | u-buyi-Ø | e | si’ |

| def | boy | A3-chop-B3 | def | wood |

‘The boy chops the wood (into tiny pieces)’

Intransitive completive

| intzaj | lok’oy-Ø | e | pe’ych |

| sweet | go.out-B3 | def | tomato |

‘The tomato turned out delicious’

Intransitive incompletive

| e | k’in | a-lok’oy | ta | ixner | k'in |

| def | sun | C1-go.out | prep | going | sun |

‘The sun sets in the west’

Common words in the Ch'orti' language

The following list contains examples of common words in the Ch'orti' language:

| all: tuno\r | ashes: tan |

| bark: pat | big: nohta |

| bite: ac\uhxop | bird: mut |

| black: negru u\t | blood: ch\ich\ |

| blow: uyuhta | bone: b\ac |

| breast: uchu\ | burn: pur |

| child: sitz/ihch\oc | cloud: tocar |

| cold: insis | come: yo\p |

| cut: xur | day: ahq\uin |

| die: cham | dig: impahni |

| dog: tz\i\ | drink: ch\I |

| dry: taquin | dust: pococ |

| ear: chiquin | earth: rum |

| eat: we\ | egg: cu\m |

| eye: naq\uiu\t | fall: c\ax |

| far: naht | fat (n.): ch\ichmar |

| fear: ap\a\cta | feather: tzutz |

| fingernail: or uyoc | fire: c\ahc |

| fish: chay | five: inmohy |

| fly (v.): top | fog: mayuhy |

| foot: oc | four: chan |

| full: b\ut\ur | give: ahc\ |

| good: imb\utzop | green: yaxax |

| hair: tzutz | hand: c\ap \ |

| head: hor | hear: oyp\ica |

| heart: alma | heavy: mb\ar |

| here: tara | hit: tz\ohy |

| horn: cachu | how?: tuc\a |

| husband: noxip | I: en |

| kill: chamse | knee: pix |

| know: na\t | lake: eha\ |

| laugh: tze\n | leaf: uyopor |

| left: utz\ehc\ap | lie: ch\a |

| liver: xemem | long: innaht |

| louse: u\ch | man: winic |

| meat: we\r | moon: uh |

| mountain: wίtzir | mouth: ti\ |

| name: uc\ab\a | near: nuťur |

| neck: nuc | new: tapop |

| night: acb\are | nose: ni\ |

| one: in | other: inmohr |

| person: winicop | pull: nquerehb\a |

| rain: haha\r | red: chacchacop |

| right: wach\ c\ab\ | river: xucur |

| road: b\i\r | root: wi\r |

| rope: ch\a\n | rope: succhih |

| rotten: oq\uem | round: gororoh |

| sand: hi\ | say: a\r |

| seed: hinah | see: wira |

| sing: c\aywi | sit: turu |

| skin: pat | sleep: way |

| smell: chuchu\ co\c | smoke: b\utz |

| stab: inxeq\ue | stand: wa\r |

| star: e\c | stone: cha\ |

| stone: tun | suck: catz\upi |

| sun: q\uin | swell: asampa |

| swim: nuhx | tail: neh |

| that: yaja\ | there: yaha\ |

| thick: pim | thin: jay |

| this: ira | thou: et |

| tongue: a\c | tooth: cha\m |

| tooth: eh | tree: te\ |

| two: cha\ | walk: axanop |

| warm: inq\uin | wash: poc |

| wash: pohch\ | water: ha\ |

| we: oŋ | wet: cuxur |

| what: tuc\a | when?: tuc\a dia |

| where?: tia\ | white: sacsac |

| who: chi | wife: wixca\r |

| woman: ihch\oc | woman: \ixic |

| year: hap | yellow: c\an |

| ye: no\x |

Extinction of the language and culture

The Ch'orti' people are descendants of the people who lived in and around Copán, one of the cultural capitals of the ancient Maya area. This covers parts of modern-day Honduras and Guatemala. Ch'orti is considered an endangered language as well as an endangered culture.

Geographic location of Ch'orti' speakers

This region is the only region in the world that Ch'orti speakers can be found. Although the area is completely shaded in, the majority of speakers reside in Guatemala, while the rest are sparsely distributed throughout the rest of the area.[13]

Honduras

The government of Honduras has been trying to promote a uniform national language of Spanish, and therefore discourages the use and teaching of native languages such as Ch'orti. The Ch'orti' people in Honduras face homogenization and have to assimilate to their surroundings. The government has been clashing with the Ch'orti people over land disputes from the 1800s, which puts the people (and thus the language) at risk. In 1997, 2 prominent Ch'orti leaders were assassinated. This assassination is just one example of many cases where Ch'orti advocates have been harmed or killed. Every one of these killings reduces the number of Ch'orti speakers. As of right now, there are only 10 remaining native speakers in Honduras.[14]

Guatemala

The government of Guatemala has been more supportive of Ch'orti speakers and has promoted programs that encourage the learning and teaching of Ch'orti. The Ch'orti's in Guatemala wear traditional clothing, unlike their counterparts in Honduras, who wear modern-day clothing.[15] Currently there are about 55,250 Ch'orti speakers in Guatemala. Even though Guatemala has established Spanish as its official language, it supports the teaching of these native languages.[16]

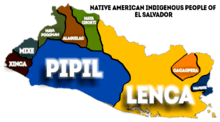

El Salvador

Chorti Maya color words

ik'ik'-black k'ank'an-yellow saksak-white yaxyax-green/blue chäkchäk-red [17]

Ethnonyms: Cholotí, Chorté, Chortí

The majority of Ch'orti' live in the Chiquimula Department of Guatemala, approximately 52,000. The remaining 4,000 live in Copán, Honduras. Traditionally, the highland Maya Indian people were dependent on maize and beans. The K'iche' Maya however, dominated the Ch'orti' dating back to the early fifteenth century. Warfare as well as disease devastated much of the Ch'orti' during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Much of their land was lost to the Guatemalan government in the nineteenth century as well. More recently, 25 percent of the Guatemalan Ch'orti' went to the United States during the 1980s to escape political persecution.[18]

Ch'orti' rosary prayers

Catata Dios / Our Father

9b Catata Dios xe' turet tichan, catattz'i ac'ab'a xe' erach.

Lar tua' ic'otori tara tor e rum wacchetaca. Y chen lo que ac'ani tara tor e rum b'an cocha war ache tichan tut e q'uin.

Ajc'unon lo que uc'ani tua' cac'uxi tama inte' inte' día.

C'umpen tacaron tamar camab'amb'anir lo que cay cache toit net, b'an cocha war cac'umpa taca tin e cay uchiob' e mab'amb'anir

capater ub'an.

Ira awacton tua' capijchna sino que corpeson tama tunor uc'otorer e diablo. Porque net jax Careyet, y net ayan meyra ac'otorer, y net ayan meyra atawarer xe' machi tua' ac'apa. Amén.[19]

Copan

The communities of Copan are populated by "farmers with indigenous tradition", essentially, agricultural laborers known as the Ch'orti'. Illiteracy rates in these communities fall between 92 and 100 percent, infant mortality rates of 60 percent, and life expectancy being 49 years for men and 55 years for women. A conflict that has effected the Copan area immensely is land tenure. Originally, Ch'orti's used communal land and owned individual plots. Shortly after the Spanish conquest, the land and people became Spanish property. The land was then used in the aparceria system (farmers rent land in return for payment of a proportion of the harvest obtained). This system was stable for hundreds of years, until the Honduran government signed Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1991. This organization was established to protect and benefit indigenous communities such as the Ch'orti' by improving access to land, health, and housing as well as other basic necessities. The murder of Ch'orti leader Candido Amador in April 1997 sparked another conflict, resulting in the government signing an agreement with the Ch'orti' organization (CONICHH) offering 2,000 ha of land in Copan.[20]

External links

- Online version of Wisdom's Chorti Dictionary (1950)

- Oral Histories of the Ch'orti' Maya (2011)

- Mayan Languages Collection of John Fought at the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America, containing several hundred recordings of Ch'orti' made between 1964 and 1967 in Guatemala, field notes and photographs.

References

- ↑ Ch'orti' at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Chorti". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ • Houston, S, J Robertson, and D Stuart. "The language of Classic Maya inscriptions." Current Anthropology 41.3 (2000): 321-356. Print.

- ↑ Keys, David. "'Lost' Sacred Language of the Maya Is Rediscovered." Mayanmajix.com. N.p., 07 Dec. 2003. Web page: http://www.mayanmajix.com/art439a.html%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ Hull, Kerry M. (2003). Verbal art and performance in Ch'orti' and Maya hieroglyphic writing [electronic resource]. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin. Available electronically from http://hdl.handle.net/2152/1240

- ↑ • Houston, S, J Robertson, and D Stuart. "The language of Classic Maya inscriptions." Current Anthropology 41.3 (2000): 321-356. Print.

- ↑ Mathews,Peter and Bíró,Péter Maya Hieroglyphs and Mayan Languages.[electronic resource] Available electronically from

- ↑ Hull, Kerry M. (2003). Verbal art and performance in Ch'orti' and Maya hieroglyphic writing [electronic resource]. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin. Available electronically from http://hdl.handle.net/2152/1240

- ↑ Hull, Kerry. (2005) "A Dictionary of Ch'orti' Maya, Guatemala." FAMSI.org Web. Available online:http://www.famsi.org/reports/03031/03031Hull01.pdf.

- 1 2 Pérez Martínez, Vitalino(1994) Gramática del idioma ch'ortí'. Antigua, Guatemala: Proyecto Lingüístico Francisco Marroquín.

- ↑ Law, Danny, John Robertson, and Stephen Houston. "Split Ergativity In The History Of The Ch'olan Branch Of The Mayan Language Family." International Journal of American Linguistics 72.4 (2006): 415-450..

- ↑ http://www.language-archives.org/item/oai:rosettaproject.org:rosettaproject_caa_swadesh-1

- ↑ • McAnany, Patricia, and Shoshaunna Parks. "Casualties of Heritage Distancing Children, Ch'orti' Indigeneity, and the Copan Archaeoscape." Current Anthropology 53.1 (2012): 80-107. Print.

- ↑ • "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples." Minority Rights Group International : Honduras : Lenca, Miskitu, Tawahka, Pech, Maya, Chortis and Xicaque. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2013. <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-25. >.

- ↑ • "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples." Minority Rights Group International : Honduras : Lenca, Miskitu, Tawahka, Pech, Maya, Chortis and Xicaque. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2013. <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-25. >.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ↑ "Chorti Maya Color Words." Native Languages. Native Languages of the Americas, n.d. Web. 27 Oct. 2013. <http://www.native-languages.org/chorti_colors.htm>.http://www.native-languages.org/chorti_colors.htm%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ Chenier, Jacqueline, and Steve Sherwood. "Copan: Collaboration for Identity, Equity and Sustainability (Honduras)." Ciesin.Columbia. Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM), n.d. Web. 27 Oct. 2013. <http://srdis.ciesin.columbia.edu/cases/Honduras-Paper.html>."http://www.everyculture.com/Middle-America-Caribbean/Ch-orti.html%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ "Ch'orti Rosary Prayer." Mary's Rosaries. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License., n.d. Web. 27 Oct. 2013. <http://www.marysrosaries.com/Chorti_prayers.html>.http://www.marysrosaries.com/Chorti_prayers.html%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ Copan: Collaboration for Identity, Equity and Sustainability (Honduras) Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine.