Lenca people

Lenca at a market in La Esperanza, Honduras | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 137,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| ~100,000e19 | |

| 37,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Honduran Spanish • Salvadoran Spanish • Formerly Lencan languages | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic | |

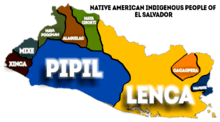

The Lenca are an indigenous people of southwestern Honduras and eastern El Salvador in Central America. They once spoke the Lenca language, which is now extinct. In Honduras, the Lenca are the largest indigenous group, with an estimated population of 100,000. El Salvador's Lenca population is estimated at about 37,000.

The pre-Conquest Lenca had frequent contact with various Maya groups as well as other indigenous peoples of the territory of present-day Mexico and Central America. The origin of Lenca populations has been a source of ongoing debate among anthropologists and historians. Research has been directed to gaining archaeological evidence of the pre-colonial Lenca.

Culture

_(20400434566).jpg)

Lenca culture developed for centuries preceding the Spanish conquest. Like other indigenous groups of Central America, they gradually changed their cultural relationships to the land.[1][2][3]

While there are ongoing political problems in contemporary Central America over indigenous land rights and identity, the Lenca have retained many of their pre-Columbian traditions. Although their indigenous language is extinct, and their culture has changed in other ways over the centuries, the Lenca continue to preserve some traditional ways and identify as indigenous peoples.

Economy

Modern Lenca communities are centered on the milpa crop-growing system. Lenca men engage in agriculture, including the cultivation of coffee, cacao, tobacco, varieties of plantains, and gourds. Other principal crops are maize, wheat, beans, squash, sugarcane, and chili peppers. In El Salvador peanuts are also cultivated. Within their communities, Lenca traditionally expect all members to participate in communal efforts.[4][5]

While there has been a growing national acceptance of indigenous rights and culture in both Honduras and El Salvador, the Lenca continue to struggle in both nations over indigenous land rights. In the mid-1990s, indigenous activists formed political groups in order to petition the government over issues of land ownership and indigenous rights. Due to the unresolved land issues, and constitutional amendments om those countries that favor land ownership by large-scale investors and agro-industrialists, there has been a decreasing amount of land for indigenous peoples. Many Lenca men have had to find employment in neighboring cities.[4]

Many Lenca communities still have their communal land. They devote the majority of cultivation to commodity crops raised for export to foreign markets. Most Lenca still use traditional agricultural practices on their own crops, as well as the crops for investors.[2]

Material culture

Lenca pottery was very distinctive. Handcrafted by Lenca women, the traditional pottery is considered an ethnic marking of their culture, as is common among traditional peoples.

In the mid-1980s, NGO cooperatives of women artisans were created in order to market their pottery. Because of a desire to increase the profitability of their arts, the cooperatives were encouraged to orient their designs and styles to meet the tastes of urban buyers, and expand their market. In the 21st century, Lenca women are making modern painted pottery (often painted black and white), which is not based on traditional designs. It has been modified to appeal to foreign buyers.[2]

Traditional Lencan pottery is still made by women in the town of Gracias, Honduras and the surrounding villages, most notably La Campa. Visitors can see demonstrations of how the traditional pottery is made. It is usually a dark orange or brick color.

Religion

The contemporary Lenca primarily practice Roman Catholicism, adopted during the colonial era. Similarly to other indigenous groups, their practices often incorporate Pre-Hispanic traditions. In addition, some Lenca communities retain more exclusively indigenous traditions. Similarly to the beliefs of other indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica, the Lenca consider sacred mountains and hills to be holy places. Many Lenca still have profound respect and adoration for the sun.

Among traditional indigenous practices are some associated with cultivation and harvest of crops. During different crop seasons, for instance, Lenca men participate in ceremonies where they consume chicha and burn incense.[5]

Guancasco

Guancasco is the annual ceremony by which neighboring communities, usually two, gather to establish reciprocal obligations in order to confirm peace and friendship. The guancascos take many forms and have adopted many Catholic representations. But they also include traditional customs and representations. Processions and elaborate exchanges of greetings, and Honduran folk dancing are performed for the statue of the patron saint of the town. Towns in central and west Honduras, such as Yamaranguila, La Campa, La Paz and Tencoa, all host the annual celebration.[6][7]

Archaeology

Until recently, archaeological research and investigation of Lenca settlements had been limited. More attention had been given to colonial-era settlements influenced by Europeans, in studies of how the cultures affected each other. In addition, many of the indigenous sites are isolated and difficult to access. Surface evidence in rural areas reveal that pre-Columbian indigenous settlements existed in many regions. Researchers may have difficulty conducting scientific excavations because the sites are found in agricultural fields under cultivation. Many surface-visible earthwork mounds have been damaged from being plowed over by rural farmers.

The evidence for pre-Columbian Lenca has come from research and excavation of several sites in Honduras and El Salvador. It shows that Lenca occupation was characterized by a relatively continuous pattern of growth, with some fluctuations.

The Comayagua Valley is located at the highland basin linking the Pacific and Caribbean drainage systems of Honduras. The valley provides evidence for a rich setting of cross-cultural relationships and Lenca settlements. According to Boyd Dixon, research in the area has revealed a complex history spanning approximately 2500 years, from the early pre-classic period to the Spanish Conquest of 1537. Prehistoric Lenca settlements were typically located along major rivers, for access to water for drinking and washing, and to waterways for transportation. The lowlands were typically fertile areas for cultivation. They built relatively small monumental public structures, which were few in number, except for military fortifications. Most constructions were made of adobe rather than stone.

In his research of the Comayagua Valley region, Dixon finds evidence of large quantities of cross-cultural relationships; many artifacts have been found that show settlements were linked through ceramics. The production of Usulua Polychrome ceramics hase been shown to link Lenca settlements with neighboring chiefdoms during the classic period. The Lenca sites of Yarumela, Los Naranjos in Honduras, and Quelepa in El Salvador, all contain evidence of the Usulután-style ceramics.[8]

Yarumela is an archaeological site believed to be a primary Lenca center within the Comayagua Valley during the middle and late formative periods. The site contained a large primary residential center several times the size of its neighboring settlements, which were secondary centers in the region. It was most likely established here because of its proximity to some of the major floodplains in the valley, which fertile soil was cultivated for agriculture. The pattern and scale of the late pre-classic settlements suggests an existence of a ranked society. All corners of the basin were located within a half-day walk of Yarumela.

Other features found in the area are at the sites of Los Naranjos, and Chalchuapa in El Salvador, each dominated by a single, constructed earthen mound. Many other sites appear to share site-planning principles and structural forms from these examples, having large, open, flat plazas, leveled by manual grading, and dominated by a massive two- to three- tiered pyramidal earthwork mound.[8][9]

Quelepa is a major site in eastern El Salvador. Its pottery shows strong similarities to ceramics found in central western El Salvador and the Maya highlands. Archaeologists speculate that Quelepa was settled by Lenca speakers from Honduras. Population pressure may have prompted their migrations to new territory.[10]

Since the late 20th century, scholars have focused on researching and exploring settlement patterns of the Lenca, in order to fill out the chronological framework for the people in the long pre-Columbian era. Research continues and such new evidence is helping to fill in the understanding of indigenous peoples of the area.[11]

Tourism

Lenca heritage tourism is expanding. It has encouraged attention to indigenous Lenca traditions and culture, especially in Honduras. The Honduran Tourism Institute, along with the United Nations Development Program, has developed a cultural heritage project dedicated to the Lenca and their culture, called La Ruta Lenca. This tourist route passes through a series of rural towns in southwestern Honduras within traditional Lenca territory. The route has designated stops in the departments of Inticuba, La Paz, Lempira, and adjacent valleys. Stops include La Campa, where traditional Lenca pottery is handcrafted by a cooperative; the archaeological sites of Los Naranjos and Yarumela; the town of Gracias, and other towns with Lenca heritage. The development of La Ruta Lenca was designed to attract tourist money to Lenca communities and to encourage preservation of remaining indigenous cultural practices by increasing the economic return for artisans and providing new markets. The project has gained some successes.[12][13]

Environmental activism

Members of the Lenca community have taken larger national roles since the late 20th century, primarily in the areas of human and land rights for the indigenous peoples, which are seen as inextricably linked. They have also been active on a variety of environmental issues, particularly trying to protect their territories against major development projects that would alter their lands and ecology. Berta Cáceres was an important leader of the Lenca and founder of the Civic Council of Indigenous and Popular Organizations of Honduras (COPINH). Cáceres strongly protested the development of the DESA Agua Zarca Hydro Project and dam on the Gualcarque River in Honduras. She was discovered murdered at her home on 3 March 2016.[14][15]

Cáceres had won the 2015 Goldman Environmental Prize for her work with the Lenca and leadership in the environmental movements.[16] She is believed to have been assassinated, and nations around the world both honored her work and pressed the government for a full investigation. A week later Indigenous activist Nelson Garcia was murdered in Intibucá.[17] A few weeks later major international investors, the Netherlands Development Finance Co. (FMO) and FinnFund, announced they would suspend funding for the Agua Zarca project.[18]

"In a news report published on June 21, a former soldier of Honduras’ Inter-Institutional Security Force (known as Fusina) alleged that Cáceres’ name, along with other environmentalists in Honduras, appeared on a military hit list."[19]

Activism against such major developments has continued to be life-threatening for indigenous people. On July 7, 2016, the body of Lesiba Yaneth was found; she was murdered the previous day in the Matamulas sector of Marcala.[20] Numerous women activists have been murdered in Honduras.

While the police initially claimed she was killed in the course of a robbery of her professional bike, Yaneth was active in COPINH. Fellow supporters believe that she was assassinated for her political work, and United Nations and European Union officials protested her death. She had opposed the Aurora hydroelectric project, planned in the municipality of San José, La Paz. This project was very important to the government; "the vice-president of the National Congress, Gladys Aurora Lopez," was reported as having "direct ties" to it.[20] On July 8, Secretary of Security Julian Pacheco said that the government had failed to provide adequate protection for Cáceres, who had received death threats. The police and military are expected to protect human rights defenders. Three suspects were arrested within a week in the Yaneth murder.[20]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Carmack 2007

- 1 2 3 Brady 2009

- ↑ Adams 1956

- 1 2 UNHCR 2008

- 1 2 Stone 1963

- ↑ Black 1995

- ↑ Griffin, Wendy. "Most guancascos celebrated in western, central Honduras". Honduras This Week. Marrder.com. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- 1 2 Dixon 1989

- ↑ McFarlane 2007

- ↑ Healy 1984

- ↑ Black 1995; Sheets 1984

- ↑ McFarlane and Stockett 2007

- ↑ Lonely Planet 2007

- ↑ Nuwer 2016;

- ↑ Bosshard 2016

- ↑ Rick Kearns, "Murdered While She Slept: Shocking Death of Berta Cáceres, Indigenous Leader and Activist", Indian Country Media, 3 March 2016; accessed 8 July 2017

- ↑ "Another Member of Berta Caceres' Group Assassinated in Honduras". teleSUR. 2016-03-15. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- ↑ Rick Kearns, "A Win in Honor of Berta Carceres? Investors Pull Funding from Controversial Project", Indian Country Media, 6 July 2017; accessed 8 July 2017

- ↑ [ Rick Kearns, "Bertha Cáceres Among Those on Honduran Military Hit List"], Indian Country Today, 27 June 2016; accessed 8 July 2017

- 1 2 3 Rick Kearns, "Another Activist Killed in Honduras, Ties to Slain Bertha Cáceres", Indian Country Today, 14 July 2016; 8 July 2017

Sources

- Adams, Richard. 1956. "Cultural Components of Central America." American Anthropologist, - Vol 58(5), 881-907

- Black, Nancy. 1995. The Frontier Mission and Social Transformation in Western Honduras: The Order of Our Lady of Mercy, 1523-1773. E.J. Brill, Leiden. ISBN 90-04-10219-1

- Bosshard, Peter, 2016 "Who Killed Berta Cáceres?" "The Huffington Post", - 03/04/2016

- Brady, Scott. 2009. "Revisiting a Honduran Landscape Described by Robert West: An Experiment in Repeat Geography," Journal of Latin American Geography - Vol 8(1),7-27

- Carmack, Robert M. with Janine L. Gasco and Gary H. Gossen. (2007). The Legacy of Mesoamerica: History and Culture of a Native American Civilization – 2nd ed. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Chapman, Anne. 1985. Los Hijos del Copal y la Candela: Ritos agrarios y tradicion oral de los lencas de Honduras. Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico City.

- Dixon, Boyd. 1989. "A Preliminary Settlement Pattern Study of a Prehistoric Cultural Corridor: The Comayagua Valley, Honduras", Journal of Field Archaeology. Vol 16(30, 257-271, via JSTOR

- Healy, P. 1984. "The Archaeology of Honduras", in The Archaeology of Lower Central America. Edited by F. Lange and D. Stone. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 113-161

- 2007. "Honduras and the Bay Islands", from Lonely Planet Publications Pty. Ltd.

- McFarlane, W. and Stockett, M. (2007). Archaeology and Community Development in the Jesus de Otoro Valley of Honduras. Paper presented at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Austin, Texas, April 26

- Minority Rights Group International, World Directory of Minorities and indigenous Peoples - Honduras: Lenca, Miskitu, Tawahka, Pech, Chortia and Xicaque, 2008

- Minority Rights Group International, World Directory of Minorities and indigenous Peoples - El Salvador: indigenous peoples, 2008

- Nuwer, Rachel. 2016. "The Rising Murder Count of Environmental Activists" "New York Times", - 6/27/2016

- Sheets, P. 1984. "The Prehistory of El Salvador: An Interpretive Summary", in The Archaeology of Lower Central America. Edited by F. Lange and D. Stone. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 85-112

- Stone, Doris. 1963. "The Northern Highland Tribes: the Lenca", in Handbook of South American Indians. Vol. 4: the Circum-Caribbean Tribes, 205-217