Chinese playing cards

Playing cards (simplified Chinese: 纸牌; traditional Chinese: 紙牌; pinyin: zhǐpái) were most likely invented in China during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). They were certainly in existence by the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271-1368).[1][2][3] Chinese use the word pái (牌), meaning "plaque", to refer to both playing cards and tiles.[4] Many early sources are ambiguous if they don't specifically refer to paper pái (cards) or bone pái (tiles). In terms of game play, there is no difference; both serve to hide one face from the other players with identical backs. Card games are examples of imperfect information games as opposed to Chess or Go.

Many western scholars, like William Henry Wilkinson, Stewart Culin, Thomas F. Carter, and Michael Dummett attribute to the Chinese the invention of playing cards. Michael Dummett even contends that the concept of suits and the idea of trick-taking games were invented in China[5]. Trick-taking games eventually became multi-trick games. These then evolved into the earliest type of rummy games during the early Qing dynasty (1644-1912). By the end of the monarchy, the vast majority of traditional Chinese card games were of the draw-and-discard or fishing variety. Chinese playing cards have proliferated into Southeast Asia by Chinese immigrants.[6] They were also formerly known in Mongolia. The direction of deals and play is counter-clockwise.

Earliest references

Playing cards may have been invented during the Tang dynasty around the 9th century AD as a result of the usage of woodblock printing technology.[7][8][9][10][11] The first possible reference to card games comes from a 9th-century text known as the Collection of Miscellanea at Duyang, written by Tang dynasty writer Su E. It describes Princess Tongchang, daughter of Emperor Yizong of Tang, playing the "leaf game" in 868 with members of the clan of Wei Baoheng, the family of the princess' husband.[9][12][13]:131 The first known book on the "leaf" game was called the Yezi Gexi and allegedly written by a Tang woman. It received commentary by writers of subsequent dynasties.[14] The Song dynasty (960–1279) scholar Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) asserts that the "leaf" game existed at least since the mid-Tang dynasty and associated its invention with the development of printed sheets as a writing medium.[14][9] However, Ouyang also claims that the "leaves" were pages of a book used in a board game played with dice, and that the rules of the game were lost by 1067.[15]

Other games revolving around alcoholic drinking involved using playing cards of a sort from the Tang dynasty onward. However these cards did not contain suits or numbers. Instead, they were printed with instructions or forfeits for whoever drew them.[15]

The earliest dated instance of a card game involving cards with suits and numerals occurred on 17 July 1294 when "Yan Sengzhu and Zheng Pig-Dog were caught playing cards [zhi pai] and that wood blocks for printing them had been impounded, together with nine of the actual cards."[15]

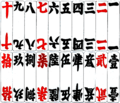

William Henry Wilkinson suggests that the first cards may have been actual paper currency which doubled as both the tools of gaming and the stakes being played for,[8] similar to trading card games. Using paper money was inconvenient and risky so they were substituted by play money known as "money cards". One of the earliest games in which we know the rules is Madiao, a trick-taking game, which dates to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Fifteenth century scholar Lu Rong described it is as being played with 38 "money cards" divided into four suits: 9 in coins, 9 in strings of coins (which may have been misinterpreted as sticks from crude drawings), 9 in myriads (of coins or of strings), and 11 in tens of myriads (a myriad is 10,000). The two latter suits had Water Margin characters instead of pips on them [13]:132 with Chinese characters to mark their rank and suit. The suit of coins is in reverse order with 9 of coins being the lowest going up to 1 of coins as the high card.[16]

Domino cards

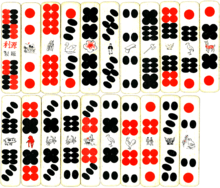

Chinese dominoes first appeared around the Southern Song dynasty and are derived from all twenty-one combinations of a pair of dice. They became available in card format around 1600.[17] Though not visually apparent, they are divided into two suits: civil and military (originally Chinese and barbarian respectively). The invention of the concept of suits increased the level of strategy in trick-taking games; the card of one suit cannot beat the card of another suit regardless of its rank. The idiosyncratic ranking and suits come from Chinese dice games.

Domino card decks come in different sizes. Smaller decks are used in trick-taking and banking games. 32-card decks, with the civil suit doubled, are used to play Tien Gow and Pai Gow. Larger decks, for rummy or fishing games, may have well over a hundred cards and can include wild cards.

Money-suited cards

Money-suited cards have attracted the most attention from scholars. They are considered to be the ancestors of most of the world's playing cards. Each suit represents a different unit of currency. Lu Rong (1436–1494) described a four-suited 38-card deck:

- Cash or Coins: 1 to 9 Cash

- Strings of Cash: 1 to 9 Strings

- Myriads of Strings: 1 to 9 Myriad

- Tens of Myriads: 20 to 90 Myriad, Hundred Myriad, Thousand Myriad, and Myriad Myriad (11 cards in total)

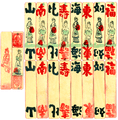

There is no 10 Myriad card as it would share the same name as its suit. By the early 17th-century, the suit of Cash added two more cards: Half Cash and Zero Cash. The Cash suit was also in reverse order with the lower number cards beating the higher. This feature also appeared in other early card games like Ganjifa, Tarot, Ombre, and Maw. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the suit of Myriads and Tens depicted characters from the novel the Water Margin which is why they were also called Water Margin cards. They were also known as Madiao cards after one of the most popular games. The suits of Cash and Strings derive their pips from early Chinese banknotes. Some cards, most commonly the highest and lowest of each suit, will have a red stamp mimicking banknote seals. On both ends of some decks are markings that serve as indices to let players fan their cards.

From at least the 17th-century, games played with stripped decks became more popular. This was done by removing the suit of Tens save for the Thousand Myriad as in the game of Khanhoo. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Thousand Myriad, Half Cash, and Zero Cash took on new identities as the suitless Old Thousand, White Flower, and Red Flower respectively. They are sometimes joined by a "Ghost" card. The Myriad Myriad card disappeared by the late 19th century. During the Qing dynasty, draw-and-discard games became more popular and the 30-card deck was often multiplied with each card having two to five copies. Jin Xueshi noted that the three-suited decks were ten times more popular than four-suited ones around 1783, a disparity which has since significantly increased.[18] Mahjong, which also exists in card format, was derived from these types of games during the middle of the 19th century.

Four-suited decks still exist and are used by the Hakka to play Six Tigers, a multi-trick game. Six Tigers decks lack illustrations and instead just have ideograms of the rank and suit of each card.[19] Another structurally similar deck is Bài Bất found in Vietnam; its three-suit version is Tổ tôm. These Vietnamese cards were redesigned by Camoin of Marseilles during French colonial rule to depict people wearing traditional Japanese costumes from the Edo period.

Direct foreign derivatives include Bài chòi in Vietnam, Pai Tai in Thailand, and Cheki in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Korean Tujeon cards were possibly a descendant.[20] Ultimately, all four-suited decks (especially Italian and Spanish suited packs) are indirectly descended from the money-suited system through Mamluk Kanjifa.

- Song dynasty coin

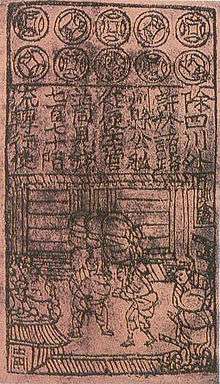

Song banknote

Song banknote- Strings of coins

Ming banknote

Ming banknote Myriad Myriad card depicting Song Jiang as illustrated by Chen Hongshou for a drinking game.

Myriad Myriad card depicting Song Jiang as illustrated by Chen Hongshou for a drinking game. Various types of Money-suited playing cards

Various types of Money-suited playing cards

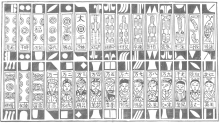

Character cards

Character cards, printed with Chinese characters, first appeared during the middle of the Qing dynasty. There are several types of character cards but are all used to play rummy-like games.[21]

Number cards are quite similar to Six Tigers packs but each deck contains only two suits and includes rank 10. Both suits are labelled in Chinese numerals but one is in ordinary script while the other is in the financial or formal script. Some decks come with special suitless cards. There are 4 copies of each card.

Great Man cards are based on a copybook called "On the Great Man (Confucius)" used by students from the Tang to the Qing dynasty. There are 24 or 25 series of cards with each series based on a character from that book. Each series contains four or five identical cards. One variation known as 3-5-7 decks, contain 27 different series but with an uneven number of cards, some have two, three, or five cards with the total being 110 cards.

Doll cards contain eight series of cards repeated eight times. One card from each series is a special version of the card differentiated from the rest by depicting a human or doll. Each series is marked by one character that when strung together forms a blessing. Included in each deck is a ninth characterless series with seven cards showing one doll and one card showing two dolls. They are found in Sichuan and Chongqing.

Unlike other types of Chinese cards, they have not spread to other countries and are largely confined to southern China.

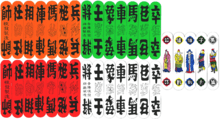

Chess cards

Cards based on Chinese chess appeared during the nineteenth century. They are generally divided into two categories, those with two suits known as Red or Fishing Cards, and those with four suits known as Four Color Cards. Each suit contains cards named after the seven different chessmen. Some decks have multiple copies of each card and may also contain "gold" wild cards. Most games are rummy-like but the two-suited Tam cúc in Vietnam is a multi-trick game.

See also

References

- ↑ Lo, Andrew. (2000). The Game of Leaves: An Inquiry into the Origin of Chinese Playing Cards. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 63(3), 389–406.

- ↑ Lo, Andrew (2000), The Late Ming Game of Ma Diao, The Playing-Card (XXIX, No. 3), pp. 115–136, The International Playing-Card Society.

- ↑ Parlett, David. The Chinese "Leaf Game". Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Lo, Andrew (2004) 'China's Passion for Pai: Playing Cards, Dominoes, and Mahjong.' In: Mackenzie, C. and Finkel, I., (eds.), Asian Games: The Art of Contest. New York: Asia Society, pp. 227-229.

- ↑ Michael Dummett, The Game of Tarot, London, p. 34-39. Carlo Penco (2013). Dummett and the Game of Tarot at Academia.edu. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ Mann, Sylvia (1990). All Cards on the Table. Leinfelden: Jonas Verlag. pp. 200–208.

- ↑ Needham 1986d, pp. 131–132.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, W.H. (1895). "Chinese Origin of Playing Cards". American Anthropologist. VIII (1): 61–78. doi:10.1525/aa.1895.8.1.02a00070.

- 1 2 3 Lo, A. (2009). "The game of leaves: An inquiry into the origin of Chinese playing cards". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 63 (3): 389. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00008466.

- ↑ Needham 2004, p. 328 "it is also now rather well-established that dominoes and playing-cards were originally Chinese developments from dice."

- ↑ Needham 2004, p. 334 "Numbered dice, anciently widespread, were on a related line of development which gave rise to dominoes and playing-cards (+9th-century China)."

- ↑ Zhou, Songfang (1997). "On the Story of Late Tang Poet Li He". Journal of the Graduates Sun Yat-sen University. 18 (3): 31–35.

- 1 2 Needham, Joseph and Tsien Tsuen-hsuin. (1985). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press., reprinted Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.(1986)

- 1 2 Needham 2004, p. 132

- 1 2 3 Parlett, David, "The Chinese "Leaf" Game", March 2015.

- ↑ Money-suited playing cards at The Mahjong Tile Set

- ↑ Lo, Andrew (2003). "Pan Zhiheng's 'Xu Yezi Pu' - Part 2". The Playing-Card. 31 (6): 281–284.

- ↑ Dummett, Michael (1980). The Game of Tarot. London: Duckworth. pp. 34–39.

- ↑ Prunner, Gernot (1969). Ostasiatische Spielkarten. Bielefeld: Dt. Spielkartenmuseum. pp. 4–13.

- ↑ Yi, I-Hwa (2006). Korea's Pastimes and Customs: A Social History (1st American ed.). Hong Kong: Hangilsa Publishing Co. p. 29.

- ↑ British Museum (1901). Catalogue of the collection of playing cards bequeathed to the Trustees of the British museum by the late Lady Charlotte Schreiber. London: Longmans. pp. 184–194.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chinese playing cards. |

- Chinese playing cards at World of Playing Cards

- Cards of China and Hong Kong at Andy's Playing Cards

- Southeast Asian cards at Andy's Playing Cards

- Money-suited playing cards at The Mahjong Tile Set

- Chinese and Southeast Asian playing cards and tiles at onebadcards

- Chinese traditional card games category at Wikipedia's Chinese language site