Chimaera

| Chimaeras | |

|---|---|

| |

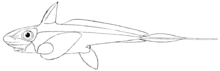

| Hydrolagus colliei | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Holocephali |

| Order: | Chimaeriformes Obruchev, 1953 |

| Families | |

Chimaeras[1] the order Chimaeriformes, known informally as ghost sharks, rat fish (not to be confused with the rattails), spookfish (not to be confused with the true spookfish of the family Opisthoproctidae), or rabbit fish (not to be confused with the family Siganidae).

At one time a "diverse and abundant" group (based on the fossil record), their closest living relatives are sharks, though their last common ancestor with sharks lived nearly 400 million years ago.[2] Today, they are largely confined to deep water.[3]

Description and habits

Chimaeras live in temperate ocean floors down to 2,600 m (8,500 ft) deep, with few occurring at depths shallower than 200 m (660 ft). Exceptions include the members of the genus Callorhinchus, the rabbit fish and the spotted ratfish, which locally or periodically can be found at relatively shallow depths. Consequently, these are also among the few species from the Chimaera order kept in public aquaria.[4] They have elongated, soft bodies, with a bulky head and a single gill-opening. They grow up to 150 cm (4.9 ft) in length, although this includes the lengthy tail found in some species. In many species, the snout is modified into an elongated sensory organ.[5]

Like other members of the class Chondrichthyes, chimaera skeletons are constructed of cartilage. Their skin is smooth and largely covered by placoid scales, and their color can range from black to brownish gray. For defense, most chimaeras have a venomous spine in front of the dorsal fin.

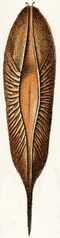

Chimaeras resemble sharks in some ways: they employ claspers for internal fertilization of females and they lay eggs with leathery cases. They also use electroreception to find their prey.[6] However, unlike sharks, male chimaeras also have retractable sexual appendages on the forehead (a type of tentaculum)[7] and in front of the pelvic fins.[5] The females lay eggs in spindle-shaped, leathery egg cases.[1]

They also differ from sharks in that their upper jaws are fused with their skulls and they have separate anal and urogenital openings. They lack sharks' many sharp and replaceable teeth, having instead just three pairs of large permanent grinding tooth plates. They also have gill covers or opercula like bony fishes.[5]

Classification

In some classifications, the chimaeras are included (as subclass Holocephali) in the class Chondrichthyes of cartilaginous fishes; in other systems, this distinction may be raised to the level of class. Chimaeras also have some characteristics of bony fishes.

A renewed effort to explore deep water and to undertake taxonomic analysis of specimens in museum collections led to a boom during the first decade of the 21st century in the number of new species identified.[2] They are 50 extant species in six genera and three families are described; an additional three genera (including the extinct genus Ischyodus) and two families are only known from fossils):

- Family Callorhinchidae Garman, 1901

- Genus Callorhinchus Lacépède, 1798

- Callorhinchus callorynchus Linnaeus, 1758 (ploughnose chimaera)

- Callorhinchus capensis A. H. A. Duméril, 1865 (Cape elephantfish)

- Callorhinchus milii Bory de Saint-Vincent, 1823 (Australian ghost shark)

- Genus Callorhinchus Lacépède, 1798

- Family Chimaeridae Bonaparte, 1831

- Genus Chimaera Linnaeus, 1758

- Chimaera argiloba Last, W. T. White & Pogonoski, 2008 (whitefin chimaera)

- Chimaera bahamaensis Kemper, Ebert, Didier & Compagno, 2010 (Bahamas ghost shark)

- Chimaera cubana Howell-Rivero, 1936

- Chimaera fulva Didier, Last & W. T. White, 2008 (southern chimaera)

- Chimaera jordani S. Tanaka (I), 1905 (Jordan's chimaera)

- Chimaera lignaria Didier, 2002 (carpenter's chimaera)

- Chimaera macrospina Didier, Last & W. T. White, 2008 (longspine chimaera)

- Chimaera monstrosa Linnaeus, 1758 (rabbit fish)

- Chimaera notafricana Kemper, Ebert, Compagno & Didier, 2010 Cape chimaera

- Chimaera obscura Didier, Last & W. T. White, 2008 (shortspine chimaera)

- Chimaera opalescens Luchetti, Iglésias & Sellos, 2011

- Chimaera owstoni S. Tanaka (I), 1905 (Owston's chimaera)

- Chimaera panthera Didier, 1998 (leopard chimaera)

- Chimaera phantasma Jordan & Snyder, 1900 (silver chimaera)

- Genus Hydrolagus Gill, 1863

- Hydrolagus affinis Brito Capello, 1868 (smalleyed rabbitfish)

- Hydrolagus africanus Gilchrist, 1922 (African chimaera)

- Hydrolagus alberti Bigelow & Schroeder, 1951

- Hydrolagus alphus Quaranta, Didier, Long & Ebert, 2006

- Hydrolagus barbouri Garman, 1908

- Hydrolagus bemisi Didier, 2002 (pale ghost shark)

- Hydrolagus colliei Lay & E. T. Bennett, 1839 (spotted ratfish)

- Hydrolagus deani H. M. Smith & Radcliffe, 1912 (Philippine chimaera)

- Hydrolagus eidolon Jordan & Hubbs, 1925

- Hydrolagus homonycteris Didier, 2008 (black ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus lemures Whitley, 1939 (blackfin ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus lusitanicus Moura, Figueiredo, Bordalo-Machado, Almeida & Gordo, 2005

- Hydrolagus macrophthalmus de Buen, 1959

- Hydrolagus marmoratus Didier, 2008 marbled ghostshark

- Hydrolagus matallanasi Soto & Vooren, 2004 (striped rabbitfish)

- Hydrolagus mccoskeri Barnett, Didier, Long & Ebert, 2006 (Galápagos ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus melanophasma K. C. James, Ebert, Long & Didier, 2009 (Eastern Pacific black ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus mirabilis Collett, 1904 (large-eyed rabbitfish)

- Hydrolagus mitsukurii Jordan & Snyder, 1904 (spookfish)

- Hydrolagus novaezealandiae Fowler, 1911 (dark ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus ogilbyi Waite, 1898

- Hydrolagus pallidus Hardy & Stehmann, 1990

- Hydrolagus purpurescens Gilbert, 1905 (purple chimaera)

- Hydrolagus trolli Didier & Séret, 2002 (pointy-nosed blue chimaera)

- Hydrolagus waitei Fowler, 1907

- Genus Chimaera Linnaeus, 1758

- Family Rhinochimaeridae Garman, 1901

- Genus Harriotta Goode & Bean, 1895

- Harriotta haeckeli Karrer, 1972 (smallspine spookfish)

- Harriotta raleighana Goode & Bean, 1895 (Pacific longnose chimaera)

- Genus Neoharriotta Bigelow & Schroeder, 1950

- Neoharriotta carri Bullis & J. S. Carpenter, 1966 (dwarf sicklefin chimaera)

- Neoharriotta pinnata Schnakenbeck, 1931 (sicklefin chimaera)

- Neoharriotta pumila Didier & Stehmann, 1996 (Arabian sicklefin chimaera)

- Genus Rhinochimaera Garman, 1901

- Rhinochimaera africana Compagno, Stehmann & Ebert, 1990 (paddle-nose chimaera)

- Rhinochimaera atlantica Holt & Byrne, 1909 (straightnose rabbitfish)

- Rhinochimaera pacifica Mitsukuri, 1895 (Pacific spookfish)

- Genus Harriotta Goode & Bean, 1895

Phylogenetics

Tracing the evolution of these species has been problematic given the scarcity of good fossils. DNA sequences have become the preferred approach to understanding speciation.[8]

The order appears to have originated about 420 million years ago during the Silurian. The 39 extant species fall into three families – the Callorhinchids, Rhinochimaerids and Chimaerids with the callorhinchids being the most basal clade. The families appear to have diverged during the late Jurassic to early Cretaceous (170–120 Mya.)

Parasites

As other fish, chimaeras have a number of parasites. Chimaericola leptogaster (Chimaericolidae) is a monogenean parasite of the gills of Chimaera monstrosa; the species can attain 50 mm in length.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2014). "Chimaeriformes" in FishBase. November 2014 version.

- 1 2 "Ancie Ghostshark From California And Baja California". ScienceDaily. September 23, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ↑ Peterson, Roger Tory; Herald, Earl S. (1 September 1999). A Field Guide to Pacific Coast Fishes: North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 13. ISBN 0-618-00212-X.

- ↑ Tozer, H. & Dagit, D.D. (2004): Husbandry of Spotted Ratfish, Hydrolagus colliei., Chapter 33 in: Smith, M., D. Warmolts, D. Thoney, & R. Hueter (editors). Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual: Captive Care of Sharks, Rays, and their Relatives. Ohio Biological Survey, Inc.

- 1 2 3 Stevens, J.; Last, P.R. (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N., eds. Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- ↑ T.H. Bullock; R.H. Hartline; A.J. Kalmijn; P. Laurent; R.W. Murray; H. Scheich; E. Schwartz; T. Szabo (6 December 2012). Electroreceptors and Other Specialized Receptors in Lower Vertebrates. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 125. ISBN 978-3-642-65926-3.

- ↑ Freaky New Ghostshark ID’d Off California Coast, a September 22, 2009 blog post from Wired Science

- ↑ Inoue, J.G., Miya, M., Lam, K., Tay, B.H., Danks, J.A., Bell, J., Walker, T.I. Venkatesh, B. (2010): Evolutionary origin and phylogeny of the modern holocephalans (Chondrichthyes: Chimaeriformes): A mitogenomic perspective. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 27 (11): 2576-2586.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chimaeriformes. |