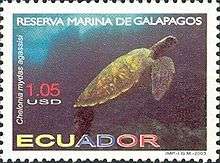

Galápagos green turtle

| Galápagos green turtle | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

Not evaluated (IUCN 2.3) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Family: | Cheloniidae |

| Genus: | Chelonia |

| Species: | C. agassizii |

| Binomial name | |

| Chelonia agassizii Bocourt, 1868 | |

The Galápagos green turtle (Chelonia agassizii) is a species of turtle that used to be classified as a subspecies of the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) but was changed for a few reasons. One, caudal dimorphism (vertebrae of the same species changing), means that Chelonia agassizii (or "Chelonia agassizi" ) has a more domed shell. Another is the colour of the shell – Galápagos green turtles have a darker shell colour. It is endemic to the tropical and subtropical waters of the Pacific Ocean.[1] They are often categorized as one population of the east Pacific green turtle.[2] This title is shared with the other green sea turtle nesting populations inhabiting the Pacific Ocean. More specifically, they are referred to as black sea turtles due to their unique dark pigmentation.[1] The Galápagos green turtle is the only population of green sea turtles to nest on the beaches of the Galápagos Islands, and this fact is the derivation of its common name.[3]

Various debates occurred over the binomial nomenclature of this population due to the distinct morphological characteristics that set them apart from other populations of green sea turtles.[4] Obtaining valid information on the lifestyles of the Galápagos green turtle has been difficult for researchers due to their continuous migrations and aquatic habits; most information has been obtained through tagging experiments.[5] The Galápagos green turtle, along with all other populations of green sea turtles, is listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List of threatened species.[6] All populations are still suffering reductions in numbers despite the many conservation efforts being practiced.[7]

Etymology

The specific name, agassizii, is in honor of Swiss-American zoologist Louis Agassiz.[8]

Physical description

Numbers of mature adult Galápagos green turtle are much lower than those of other green sea turtle populations; this may be why they are more genetically isolated than other populations.[9] The carapace is dark in color, usually black to dark olive-brown, is oval in shape, and tapers toward the tail.[10] The carapace has a distinctive formation that is more sloped or domed than individuals of other populations.[9] The five vertebral scutes are all alike in size with a hexagonal shape and flat edges.[10] The lateral scutes are similar in size, but only four occur along each side.[10] The carapace is tougher than the plastron, or the underside of the shell, and is also darker in pigmentation.[9] They have been recorded up to 84 cm in length,[10] while other green sea turtles have been recorded up to 99 cm in length.[11] Their legs are shaped like flippers to aide in swimming; they are broad and generally flattened.[11] The head is rounded and lizard-like with no teeth and does not have the predominantly hooked beak like many other green sea turtles.[10] The sexes are similar in most aspects except size; the females are slightly larger, and the males have a longer tail.[9]

Habitat

Galápagos green turtles get their name from their specific nesting habitat, the Galápagos Islands. They are the only subpopulation of sea turtles to nest in these islands.[12] The 17 Galápagos Islands straddle the equator off the coast of Ecuador and are volcanic in origin.[3] This is not their only habitat, as they are a highly migratory species and spend much of their time cruising the warm waters of the Pacific Ocean.[3] Colonies of green sea turtles have been observed nesting in 80 countries around the globe, and they forage along the coasts of about 140 countries.[6] Galápagos green turtles been recorded from the Baja California peninsula to the Galápagos Islands and Peru, and as far west as the Hawaiian and Marshall Islands.[13] Much of their time near shore is spent foraging and resting.[3] Black sea turtles have been recorded to spend much of their time in the bays and lagoons of the Baja California peninsula foraging and resting.[1] Distances of migration are recorded to range between 1233 and 2143 km and are performed over various time periods.[3] They come to the Galápagos primarily to nest and only the females come ashore and lay eggs; the males stay submerged for most of their lives.[5]

Reproduction

Female Galápagos green turtles most often only lay eggs every 2–3 years and spend the time between resting and foraging.[11] Fertilization occurs under water with only females emerging for nesting.[5] Mating has not been witnessed outside of the nesting season and usually occurs off shore near the nesting sites.[14] Nesting space can be somewhat limited due to the consistency of the beaches in the Galápagos, being of volcanic origin.[14] Many rocky areas and cliffs are present, with limited space on sandy beaches.[14] Also, the sandy areas tend to be quite dry, and this causes many cave-ins of the nests.[14] Females in the Galápagos have modified their nesting habits due to this factor and usually keep one hind flipper in the nest while depositing the eggs to prevent the unwanted cave-in.[14] Clutch size varies from 50 to 200 eggs per nest and can take up to three hours to accomplish.[11] However, Galápagos green turtles are known to have smaller clutch sizes than other populations.[14] After the eggs are laid, the female covers them with sand and presses down with her plastron for compaction.[11] They have also been noted to make a false nest next to their primary nest to try to fool predators.[14] When leaving, the female turtle attempts to cover any trace of her presence by flinging sand around in the nest area.[11]

Nesting most often occurs at night for protection from predators.[5] The prime season for nesting is from December to June,[1] butr peak months are January through March.[14] Females are uneasy when coming ashore. If they feel threatened, they return to the water and wait until the shore is safer.[14] Approximately two months after nesting the hatchlings emerge.[11] They are around 46 mm long when hatched, smaller than other Chelonia hatchlings.[14]

History

Galápagos green turtles have been recorded and observed in the Galápagos as far back as the 17th century by William Dampier.[3] Not much attention has been paid to them due to the overwhelming research done on the Galápagos giant tortoises.[14] Only over the last 30 years have extensive studies been performed covering the behaviors of the Galápagos green turtles. Much of the debate that has surrounded them recently is over the binomial classification of the species.[4] It is the only subpopulation of green sea turtle to be given premise for separate species delineation, proposing Chelonia agassizii as a separate species.[13] At this time, no distinctions have been made, mainly due to analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA of 15 nesting beaches.[4] This analysis has showed little distinction between the populations of the East Pacific waters and those of other nesting areas.[4]

The unique morphological distinctions of the Galápagos green turtle have given rise to the debate.[13] The two most notable distinctions are the considerably smaller adult size and the much darker pigmentation of the carapace, plastron, and extremities.[13] Other distinctions are the curving of the carapace above each hind flipper, the more dome-shaped carapace, and the very long tail of adult males.[9] The main argument that separates C. agassizii from other Chelonia species is that with a smaller adult size, mating with a female black sea turtle would be very difficult for a male of another subpopulation.[9] A male sea turtle must have a fairly strong hold of the female's carapace during mating to successfully copulate; with the female C. agassizii being much smaller, this feat would be impossible.[9] This, in turn, creates an isolation of C. agassizii from the genetic variations shared by other populations of green sea turtles in the Pacific.[9]

Three possibilities have arisen from their unique characteristics: C. agassizii is a separate species from C. mydas, it is a subspecies of green sea turtle, or it is simply a color mutation.[9]

Behavior

Galápagos green turtles’ lifestyle is similar to other populations of Chelonia. The behavior of all sea turtles is difficult to track, but many tagging experiments have been performed to assess migration patterns[5] and feeding habits of Chelonia species in the eastern Pacific.[2] The results of this research indicates that the green sea turtles of the eastern Pacific, including the Galápagos green turtles, are highly migratory, and they feed on many different forage species, including some animal matter.[2] Female green turtles are known to nest colonially and to return to the same nesting beach every time they reproduce.[5] This may be a result of comfort from past nesting success or it could be a result of returning to the origin of their own hatching beach.[5] Populations in the eastern Pacific have also been shown to return to the same foraging habitat after nesting, and these areas are shared with other nesting colonies.[5] Analysis of genetic data shows that populations in the eastern Pacific share the same life history, but have developed variations of many details such as size and color.[5] The populations in the Pacific and Indian Oceans are shown to have complete genetic isolation from the populations in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea.[5] Black turtles are recorded to spend much of their maturation stage in the coastal areas off the Baja California peninsula, in particular in the Bahia Magdalena lagoon and connecting channels.[1] This particular area is rich in mangrove trees that provide forage and protection during this crucial stage of their lives.[1] Another food source for the mature green turtles in the Pacific is marine algae, and red algae are common along with green algae and eelgrasses.[2] This has been observed off the Bahia de los Angeles.[2] In this area, they have also been noted to consume many forms of animal matter, as well.[2] This may be incidental or intentional in origin, but results are unclear.[2] If incidental, it may be a result of consuming marine algae near the invertebrates or if intentional it may be to provide important nutrients, minerals, or proteins not obtained from vegetation.[2]

Behaviors of hatchlings differ from that of adults. After a hatchling emerges from the sand, it immediately goes out to sea.[7] Hatchlings use the light of the night sky to find their way into the ocean.[11] However, in many areas with coastal development, the hatchlings become confused from false light and sometimes move in the wrong direction to their deaths;[11] this is not as much of a problem for Galápagos green turtles due to lack of development in the islands. Importantly, the hatchlings emerge at night to be protected from predators.[7] They quickly move out to sea and swim for up to 24 hours to be far removed from shore and the predators in that area.[7] They spend many years in the open ocean before entering the coastal habitat for the maturation period as juveniles.[1] This period of maturation lasts from 10 to 20 years; black sea turtles usually spend time along the coasts of the Baja California peninsula and the connecting bays, lagoons, and channels that provide excellent forage and protection.[1]

Economic significance to humans

Now that the Galápagos green turtle is an endangered species, it has little economic significance for humans.[6] They have in the past been harvested from egg to adult phases for various human uses.[6] The eggs and meat from all life stages was used in many areas as a food source for humans, and the meat is still considered a delicacy in some countries of South America.[1] They were also harvested for their hides and for the oils of their fat deposits used in cooking, but the Galápagos green turtle has less body fat than other green turtles, so not as much oil was yielded from their bodies.[14] Now the green turtles have more of a negative impact on human economics due to their status as endangered.[6] They are often involved as bycatch in many ocean fisheries and are protected through many acts of legislation.[1]

Conservation status

Galápagos green turtles, grouped with all populations of Chelonia mydas, are listed on the IUCN Red List of threatened species.[6] They were placed on the list in the mid 1980s and have remained under protection since.[6] One of the major problems that have led to their decline is the slow growth rate and long period from juvenile to sexual maturity.[6] Chelonians average a period of 26–40 years to maturity; the Galápagos green turtle averages 33 years.[6] The green sea turtle has been shown to have the slowest growth rate of any species of sea turtle and is generally long-lived if left undisturbed.[6] Overall, populations of C. mydas have had a decrease of about 48–67% of nesting females, but the population that nests in the Galápagos has remained quite steady with little to no change.[6] The population of nesting females recorded in the Galápagos from 1976–1982 was roughly 1400 individuals and after further evaluation in 1999–2001, around 1400 nesting females were found.[6]

Reductions in populations of C. mydas are recorded in every ocean ecosystem they inhabit, and the contributing factors that have led to their decline are all anthropogenic.[6] The main threats are harvesting of eggs and individuals, bycatch in marine fisheries, and degradation of the marine and coastal habitats.[6] The most common accidental threat is the entanglement in fishing equipment with the most harmful methods being drift netting, shrimp trawling, long-lining, and dynamite fishing.[6] Many pieces of legislation now ban these practices in protected areas.[6]

For chelonians inhabiting the eastern Pacific, including the Galápagos green turtle, the threats are the same. The main factor leading to decline in this area was the intense and unregulated fishing operations run off the coast of Mexico between 1950 and 1970.[1] In many countries in Central and South America, the meat of sea turtles is considered a delicacy and they are to this day poached and hunted directly.[1] The mortality of the sea turtles near their foraging area of the Baja California peninsula is around 7800 deaths yearly, which has led many organizations to rally for governmental protection of this area for the species.[1] Around 9 out of 100 individuals survive a year in the waters of the Baja California peninsula; this in an intense foraging ground for all population in the eastern Pacific.[1] Even with the passing of new protective legislation and the many efforts of conservation organizations, populations are continuing to decline, and considering the long generation time of 42.8 years, recovering from any hit on the population is difficult.[6]

One of the many conservation efforts being implemented to increase populations now is the use of hatcheries for protected egg incubation,[7] the goal of which is to create a protected environment for the hatchlings where they can incubate and emerge from the sand without threat of predators and then be released out to sea safely.[7] Unfortunately, this result has not been documented in practice. Often, when hatchlings emerge from the sand in the incubator, they remain enclosed inside and expend much of their preserved energy trying to find a way out.[7] They also lose the extremely important dark, night hours used to get far away from shore.[7] They are released out to sea, often in the early morning hours, when many predators are about, which limits their chance of survival.[7] In addition, the hatchlings are also often too weak to gain a long distance from shore due to the energy lost in the incubator after hatching.[7] These results have led many to believe that hatcheries are ineffective and should only be used as a last resort.[7] No extensive research has shown the survival rate of the hatchlings after they are released to sea, but one study proclaimed a possible 50% loss after release.[7]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chelonia mydas agassizi. |

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Koch, Volker; Brooks, Louise B.; Nichols, Wallace J. (2007). "Population Ecology of the Green/Black turtle (Chelonia mydas) in Bahia Magdalena, Mexico". Marine Biology. 153: 35–46. doi:10.1007/s00227-007-0782-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Seminoff, J. A.; Resendiz, Antonio; Nichols, Wallace J. (2002). "Diet of East Pacific Green Turtles (Chelonia mydas) in the Central Gulf of California, Mexico". Journal of Herpetology. 36 (3): 447–453. doi:10.2307/1566189.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Green, Derek (1984). "Long-Distance Movements of Galapagos Green Turtles". Journal of Herpetology. 18 (2): 121–130. doi:10.2307/1563739. JSTOR 1563739.

- 1 2 3 4 Parham, J. F.; Zug, G. R. (1996). "Chelonia agassizii – Valid Or Not?". Marine Turtle Newsletter. 72: 2–5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bowen, Brian W.; Meylan, Anne B.; Ross, J. Perran; Limpus, Colin J.; Balazs, George H.; Avise, John C. (1992). "Global Population Structure and Natural History of the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) in Terms of Matriarchal Phylogeny" (PDF). Evolution. 46 (4). JSTOR 2409742.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Seminoff, J.A. (2004). "Chelonia mydas". 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Pilcher, Nicolas J.; Enderby, Simon (2001). "Effects of Prolonged Retention in Hatcheries on Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) Hatchling Swimming Speed and Survival". Journal of Herpetology. 35 (4): 633–638. doi:10.2307/1565902. JSTOR 1565902.

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Chelonia mydas agassizii, p. 2).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Pritchard, Peter C. H. (1999). "Status of the black sea turtle". Conservation Biology. 13 (5): 1000–1003. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98432.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Swash, Andy; Still, Rob (2006). Birds, Mammals, and Reptiles of the Galápagos Islands: An Identification Guide, 2nd Edition. Yale University Press. p. 116.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Chelonia mydas, green sea turtle". MarineBio.org. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ↑ Green, Derek (1993). "Growth Rates of Wild Immature Green Turtles in the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador". Journal of Herpetology. 27 (3): 338–341. doi:10.2307/1565159. JSTOR 1565159.

- 1 2 3 4 Karl, Stephen A.; Bowen, Brian W. (1999). "Evolutionary Significant Units versus Geopolitical Taxonomy: Molecular Systematics of an Endangered Sea Turtle (Genus Chelonia)". Conservation Biology. 13 (5): 990–999. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.97352.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Pritchard, Peter C (1971). "Galápagos Sea Turtles – Preliminary Findings". Journal of Herpetology. 5 (1/2): 1–9. doi:10.2307/1562836. JSTOR 1562836.