Influence of Italian humanism on Chaucer

Contact between Geoffrey Chaucer and the Italian humanists Petrarch or Boccaccio has been proposed by scholars for centuries.[1] More recent scholarship tends to discount these earlier speculations because of lack of evidence. As Leonard Koff remarks, the story of their meeting is "a 'tydying' worthy of Chaucer himself".[2]

One of the reasons for the belief that Chaucer came in contact with Petrarch or Boccaccio is because of Chaucer's many trips to mainland Europe from England. Chaucer happened to be in the same areas at the same time as Petrarch and Boccaccio. Another reason is the influence of Petrarch's and Boccaccio's works on Chaucer's later literary works.

Chaucer's trips to mainland Europe

Chaucer had made several trips to the mainland from England between 1367 and 1378 on the King's business as Esquire of the King.[3] During at least one of these trips it is possible that he met Petrarch or Boccaccio or possibly both in Italy.[4][5] Historian Donald Howard, Professor Walter William Skeat and Dr. Furnivall say there is good evidence to indicate that Chaucer met Petrarch at Arqua or Padua.[6][7]

There are government records that show Chaucer was absent from England visiting Genoa and Florence from December 1372 until the middle of 1373.[6][8] He went with Sir James de Provan and John de Mari, eminent merchants hired by the king, and some soldiers and servants.[8][9] During this Italian business trip for the king to arrange for a settlement of Genoese merchants these scholars say it is likely that sometime in 1373 Chaucer made contact with Petrarch or Boccaccio.[6][10]

Milan 1368: The wedding of the Duke of Clarence and Violante Visconti

Chaucer became a member of the royal court of King Edward III as a valet or esquire in June 1367.[11] Among his many jobs in this position he travelled to mainland Europe many times.[11] On one of these trips in 1368 Chaucer may have attended the wedding which took place in Milan on 28 May or 5 June[12] between Edward's son Prince Lionel of Antwerp and Violante, daughter of Galeazzo II Visconti, Lord of Milan. [13] The above scholars write that he was likely introduced to Petrarch at this wedding.[13][14][15] Jean Froissart was also in attendance and perhaps Boccaccio.[16] They believe it plausible that Chaucer not only met Petrarch at this wedding but also Boccaccio.[8][13] This view today, however, is far from universally accepted. William T. Rossiter, in his 2010 book on Chaucer and Petrarch argues that the key evidence supporting a visit to the continent in this year is a warrant permitting Chaucer to pass at Dover, dated 17 July. No destination is given, but even if this does represent a trip to Milan, he would have missed not only the wedding, but also Petrarch, who had returned to Pavia on 3 July.[12]

Biographers suggest that Chaucer very well could have met Petrarch personally, not only at the wedding of Violante in 1367, but also in Padua sometime in 1372–1373.[17]

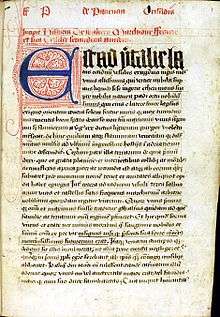

Griselda

Petrarch's letter to Boccaccio, forming a preface to the tale of Griselda, was written shortly after Petrarch had made his version of Griselda.[18] In some copies Petrarch's version of the story of Greselda has a date of "June 8, 1373", which indicates the date of supposed composition.[18] Petrarch was so pleased with the story of Griselda ("De Patientia Griseldis") that he put it to memory.[18] He wanted to repeat the virtuous story to his friends, perhaps including Chaucer.[18][19] He eventually translated it into Latin, a common poetic language of the time (and, to Petrarch, a more prestigious language than the Italian vernacular).[18] Therefore, scholars conclude that Chaucer and Petrarch met at Padua in 1373, probably the early part of the year.[18][19] According to Skeat, evidence shows that Petrarch told Chaucer the story of Griselda from memory (though this may be speculation).[18][19] Since both knew Italian and French, they might have communicated in either language or a combination of both these languages.[6][18] It is evident that Chaucer obtained a copy of Petrarch's version written in Latin shortly after the meeting in Padua.[6][18] Petrarch died 19 July 1374.

Chaucer translates the story of Griselda into English where it became part of The Canterbury Tales as The Clerk's Tale.[6][18] Scholars speculate that he wrote the main part of the Clerk's Tale in the later part of 1373 or the early part of 1374, shortly after his first trip to Italy in 1372–73.[20] Chaucer gives much praise to Petrarch and his writings.[20] The Originals and Analogues of some of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, reprinted and published for the Chaucer Society in 1875, assert that Chaucer personally met Petrarch. Many quotations are properly marked in the margins of the pages of the versions in the Ellesmere and Hengwrt manuscripts with each in the correct places. Scholars conclude that it is quite clear that Petrarch personally gave Chaucer a version of Griselda at Padua in 1373 (though this idea was proposed in the late 19th century, and more recent scholars are more sceptical of propositions that cannot be proven).[21]

Influence of Petrarch's and Boccaccio's works

Chaucer produced works with much Italian influence after his Italian trip of 1372, whereas works written before his travel demonstrate French influence.[22][23] Chaucer's stories imitate, among others, his Italian contemporaries Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio. For example, Boccaccio first put out his stories of The Decameron; then Chaucer imitated many of these stories for his Canterbury Tales.[10][24][25]

Canterbury Tales

The Clerk's Tale

Boccaccio wrote the story of Griselda, which was later translated by Petrarch. Biographers say Chaucer heard it from Petrarch first by word of mouth at Padua.[26] Later he received a Latin copy of it that he used to develop The Clerk's Tale.[26][27][28] Many passages of The Clerk's Tale are nearly word for word of Petrarch's Latin version of Griselda.[29]

In the prologue to The Clerk's Tale, the narrator suggests that he met Petrarch:

| “ | The which that I Learn'd at Padova of a worthy clerk, As proved by his wordes and his werk. He is now dead, and nailed in his chest, I pray to God to give his soul good rest. Francis Petrarc', the laureate poete, Highte this clerk, whose rhetoric so sweet Illumin'd all Itaile of poetry... But forth to tellen of this worthy man, That taughte me this tale, as I began...[3][20] | ” |

However, this does not mean necessarily that Chaucer himself met Petrarch.

The Monk's Tale

Chaucer's Monk's Tale may also be based on Boccaccio's De Casibus Virorum Illustrium.[30][31] This was a classical tradition of historiography dealing with famous men, which began with Plutarch's Parallel Lives.[32] Chaucer's incipit reads: "Heer bigynneth the Monkes Tale De Casibus Virorum Illustrium." (Here begins the Monk's Tale "De Casibus Virorum Illustrium" – "On the Fates of Illustrious Men").[31] Many of the famous people that are in The Monk's Tale are also in Boccaccio's De Casibus Virorum Illustrium: Adam, Samson, Hercules, Cenobia, Nero, Alexander the Great, Croesus.[33] Some of these people also appear in Petrarch's De Viris Illustribus.[34] Chaucer, however, credits only Petrarch for this work:

The Knight's Tale

Some of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales are based on Boccaccio's works.[37] For example, Chaucer's first of these tales, The Knight's Tale, is a condensed version of Boccaccio's Teseida.[37] Chaucer tightens the structure of Boccaccio's Teseida, changes some scenes in the general plot, and deepens the philosophy of the original. In The Knight's Tale, Arcite calls himself "Philostrate", an allusion to the title of Boccaccio's Filostrato. Chaucer thereby alludes to the fact that Filostrato and Teseida are from the same author – Boccaccio.

Other Canterbury Tales

Chaucer's Shipman's Tale has similar features to Boccaccio's Decameron part 8,1.[38] In Chaucer's The Merchant's Tale "January's" love-making can be attributed to Boccaccio's Comedia delle ninfe fiorentine.[38] Chaucer's The Franklin's Tale draws on Boccaccio's Filocolo IV.31-4.[38] Chaucer imitates Boccaccio's De casibus 8,6 of the character Zenobia in The Monk's Tale.[39] The character Zenobia (a.k.a. Cenobia) Chaucer mistakenly credits to Petrarch (mentioned in his Triumph of Fame), whereas the character originally came from Boccaccio in his 106 list On Famous Women.[40]

Other works

The Legend of Good Women

Chaucer followed the general plan of Boccaccio's work On Famous Women in The Legend of Good Women.[31][37][42] Both works are of famed women, draw on classical mythology and history, are in chronological order, give a synopsis as an introduction, and are dedicated to a queen.[42] Chaucer's "Cenobia" is borrowed from Boccaccio's Zenobia of De mulieribus claris.[41] Chaucer also borrowed information of certain women from Boccaccio's De Casibus Virorum Illustrium and Genealogia Deorum Gentilium.[38][39][43]

House of Fame

Chaucer's House of Fame was probably begun in 1374; considered one of his greatest works, it has much Italian influence.[23][44] This work shows the Italian influence on Chaucer after being in Florence in 1373 and returning to Milan in 1378.[45] Chaucer claims that "Lollius" was the source for the House of Fame, when in fact it came straight from Boccaccio's Il Filostrato. There are also likenesses between this work of Chaucer's and Boccaccio's Amorosa visione.[38]

Troilus and Criseyde

In Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde, Troilus's lament after he has fallen in love song imitates Petrarch's sonnets, S'amor non-e, che dunque e quel ch' i' sento? ("If this be not love?") adapted from the Filostrato.[40][46] Here Troilus's mode of thought is a Petrarchan combination of intelligent introspection, private emotion and scholastic logic.[47] As far as scholars know, this is the first known adaptation of a Petrarch sonnet in English.[47] Some believe that Troilus' later song (V.638-44) may imitate Petrarch's sonnet 189 ("My galley charged with forgetfulness").[47]

Alternative viewpoints

Other historians assert that while Chaucer was on mainland Europe in 1372–73 and it could have been possible that he met Petrarch or Boccaccio, it is unlikely because of their different social statuses.[48] Most however, agree, that whether Chaucer ever met Petrarch or Boccaccio, he was heavily influenced by their works.

Nevertheless, Howard argues that only inconceivable coincidences could permit that Chaucer had not known Boccaccio.[49] The following coincidences would have to have taken place:[49]

- By serendipity two or three of Boccaccio's works would have to have fallen into the hands of Chaucer and he just happened to have made adaptations of them.[49]

- A few other of Boccaccio's works by serendipity would have to have fallen into Chaucer's hands and he quoted from them.[49]

- Chaucer would have to have, by chance, imitated several of Boccaccio's works, like Decameron.[49]

- Chaucer was in Florence when Boccaccio was there at the same time, however something would have to have prevented the two great poets from meeting each other.[49]

- Chaucer knew the famous Visconti family, as did Boccaccio, however a meeting between the two would have to have been precluded despite this high-profile mutual connection.[49]

The more plausible scenario for Howard indicates that Chaucer personally met Boccaccio.[49] Chaucer likely knew more Boccaccio works than scholars can prove.[49] It is certain that Chaucer had access to Boccaccio's Filostrato and Teseida because of the quality of imitations in The House of Fame and Anelida and Arcite.[38] The Knight's Tale uses Boccaccio's Teseida and the Filostrato is the major source of Troilus and Creseyde.

Footnotes

- ↑ Thomas Warton, The history of English poetry, from the close of the eleventh to the commencement of the eighteenth century (first published London: J. Dodsley, etc.; Oxford: Fletcher, 1774–81) and William Hazlitt, Lectures on the English poets: delivered at the Surrey Institution (first published London: Taylor and Hessey, 1818): both extracted in Brewer 1995, pp. 226–30 (p.227) and 272–83 (p. 277)

- Hendrickson 1907, pp. 183–192

- Rearden 1882, p. 458

- Skeat 1900, pp. 382, 453, 454, 455

- Gardner 1999, p. 198

- Howard 1987, p. 190

- Gray 2003, p. 56

- Coulton 1908, p. 42 ...Speght writing in 1598...

- THE GEOFFREY CHAUCER PAGE – Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375)

- ↑ Koff 11

- 1 2 anon, The World of Chaucer 2008

- Cousin 1910, p. 167

- Guiney 1908

- Boitani 1985

- Coulton 1908, p. 45

- ↑ Liukkonen 2008

- ↑ Skeat 1910

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Skeat 1900, p. 454 (Scholars being Professor Walter William Skeat and Dr. Furnivall)

- ↑ Coulton 1908, p. 40

- 1 2 3 Gray 2003, p. 251

- ↑ Howard 1987, p. 169

- 1 2 Howard 1987, p. 191

- 1 2 Crow, Martin M. et al, Chaucer Life-records.

- 1 2 Rossiter 2010

- 1 2 3 Thomas Warton, The history of English poetry, from the close of the eleventh to the commencement of the eighteenth century (first published London: J. Dodsley, etc.; Oxford: Fletcher, 1774–81) extracted in Brewer 1995, pp. 226–30 (p.227))

- ↑ Howard 1987, p. 189

- ↑ Curry 1869, pp. 157, 158, 159

- ↑ Warton 1871, p. 296 (footnotes: Froissart was also present.)

- ↑ Meiklejohn 1887

- Coulton 1908, p. 41

- Coulton 1908, p. 44

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Skeat 1906

- 1 2 3 Ames 1900, p. 98

- 1 2 3 Skeat 1900, pp. 382, 453, 454, 455

- ↑ Skeat 1894, pp. 454–456

- ↑ Skeat (1900), p. xvii

- 1 2 Borghesi 1903, p. 20

- ↑ Boccaccio's Decameron

- ↑ Florence Nightengale Jones (1910). Boccaccio and his imitators in German, English, French, Spanish, and Italian literature, The Decameron. The University of Chicago Press – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 Warton 1871, p. 349

- ↑ anon, American Society for the Extension of University Teaching 1898, p. 82

- ↑ What's Really Being Tested in The Clerk's Tale?

- ↑ Skeat (1906), p. 196 (#57)

- ↑ Boitani, p. 291

- 1 2 3 The Chaucer Review, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 163–165 (Fall, 1989), p. 164; Penn State University Press

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Petrarch". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010.

- ↑ Boccaccio

- ↑ Wallace, Chaucerian Polity (Bishop)

- ↑ The Monk's Tale – Middle English

- ↑ The Monk's Tale – Modern English

- 1 2 3 Howard 1987, p. 195

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gray 2003, p. 57

- 1 2 Gray 2003, p. 58

- 1 2 Gray 2003, p. 375

- 1 2 Skeat (1906), p. 182

- 1 2 Skeat (1900), p. xxviii

- ↑ Skeat (1900), p. xxix

- ↑ "Boccaccio and Chaucer" by Peter Borghesi, Bologna, 1912

- ↑ Howard 1987, p. 187

- ↑ Ames 1900, p. 99

- 1 2 3 Gray 2003, p. 376

- ↑ anon, Did Chaucer meet Petrarch

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Howard 1987, p. 282

Sources

- Ames, Percy Willoughby (1900). Chaucer memorial lectures. Asher and Co., London. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- American Society for the Extension of University Teaching, The Citizen, Volume 3, American Society for the Extension of University Teaching, 1898, University of Michigan

- Bell, G. & Sons, 1912, The age of Chaucer (1346–1400), p. 152, Indiana University

- Boitani, Piero (1985). Chaucer and the Italian Trecento. CUP Archive. ISBN 0-521-31350-3. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Borghesi, Peter (1903). Boccaccio and Chaucer. Princeton University: N. Zanichelli. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Brown, Peter, A companion to Chaucer, pp. 454–456, Wiley-Blackwell, 2002, ISBN 0-631-23590-6

- Brewer, Derek, ed. (1995). Geoffrey Chaucer: The Critical Heritage: 1385–1837. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13398-X. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Chambers, Robert, Cyclopaedia of English literature: a selection of the choicest productions of English authors from the earliest to the present time, World Publishing House, 1875, from HUP

- Chaucer, Geoffrey, The works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Publisher Macmillan, 1898, Harvard University

- Chaucer, Geoffrey (2001). "The Canterbury Tales and Other Poems". The Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Cook, Albert Stanburrough (1916). "The Last Months of Chaucer's Earliest Patron". Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. 21: 1–144. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Coulton, George Gordon (1908). Chaucer and his England. Methuen, London. at Internet Archive

- Coulton, George Gordon (1965). Chaucer and his England. Routledge. ISBN 0-416-67970-6. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- Cousin, John W. (1910). A short biographical dictionary of English literature. Plain Label Books. ISBN 1-60303-696-2. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Crow, Martin M. et al., Chaucer Life-records, Clarendon Press, 1966. It includes materials such as receipts for his travels in Italy, copies of commissions, etc.

- Curry, William (1869). The Dublin University magazine, Volume 74. Princeton University: William Curry, Jun., and Co. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Dempster, Germaine (1943). "Chaucer's manuscript of Petrarch's version of the Griselda story". Modern Philology. University of Chicago Press. 41 (1): 6–16. doi:10.1086/388598. JSTOR 433948.

- Edmunds, Edward William, Chaucer & his poetry, Volume 26 of Poetry & life series, p. 50, C.G. Harrap & Company, 1914

- Farrell, Thomas J. (2003). "Source or Hard Analogue? Decameron X, 10 and the Clerk's Tale". The Chaucer Review. 37 (4). Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Finlayson, John (2000). "Petrarch, Boccaccio, and Chaucer's Clerk's Tale". Studies in Philology. xcvii (3): 255–275. JSTOR 4174672.

- Gardner, John (1999). Life and Times of Chaucer. Princeton University: Barnes & Noble Publishing. ISBN 0-394-49317-6. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Garnett, Richard, English literature : an illustrated record, Heinemann, 1906, from University of Michigan

- Ginsberg, Warren (2001). "Chaucer's Italian Tradition" (PDF). University of Michigan Press. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Gosse, Edmund, English literature : an illustrated record, p. 137, Heinemann, 1906. University of Michigan

- Guiney, Louise Imogen (1908). "Geoffrey Chaucer". New Advent. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Gray, Douglas (2003). The Oxford Companion – Chaucer. Oxford University: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-811765-5.

- Hales, John Wesley (1887). "Chaucer, Geoffrey". In Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography. 10. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Hammond, Eleanor Prescott, Chaucer: a bibliographical manual, p. 306, The Macmillan Company, 1908

- Hendrickson, G.L. (1907). Modern philology, Volume 4, complete detailed analysis as to Chaucer coming in contact with Petrarch and Boccaccio. Harvard University: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Howard, Donald R. (1987). Chaucer, his life, his works, his world. E. P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24400-X. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- Hunt, Leigh, Leigh Hunt's London journal, Volumes 1–2, C. Knight, 1834

- Hutton, Edward, Giovanni Boccaccio: a biographical study, J. Lane, 1910, University of California

- James Clarke & Co., The literary world, Volume 21, 1880, p. 251, Princeton University

- Jenks, Tudor, In the days of Chaucer, p. 144, A. S. Barnes & company, 1904, Harvard University

- Johns Hopkins University, Modern language notes, Volume 12 No. 1, Johns Hopkins Press, 1897

- Jusserand, J.J., The Twentieth century, Volume 39, The Nineteenth Century and After, 1896, pp. 993–1005, detailed analysis of Chaucer coming in contact with Petrarch in 1373. UOM

- Koff, Leonard Michael. "Introduction". The Decameron and the Canterbury Tales: New Essays on an Old Question. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2000.

- Langer, William Leonard, An encyclopaedia of world history, ancient, medieval and modern ..., Volume 1, p. 267, Houghton Mifflin Co., 1948

- Meiklejohn, John Miller Dow (1887). "English Language and Literature – Geoffrey Chaucer". A Brief History of the English Language and Literature, Volume 2. The Project Gutenberg EBook / D. C. Heath & Co. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Rossiter, William T. (2010). Chaucer and Petrarch. Chaucer studies. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-84384-215-6. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Rutherford, Mildred Lewis, French authors: a hand-book of French literature , p. 39, The Franklin Printing and Publishing Company, 1906, Princeton University

- Schibanoff, Susan, Chaucer's queer poetics: rereading the dream trio, p. 316, University of Toronto Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8020-9035-4

- Skeat, Walter William (1894). The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer (vol 3): The house of fame:The legend of good women: The treatise on the Astrolabe: Canterbury tales text. Clarendon press. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- Skeat, Walter William (1900). The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer (vol 3–4): The house of fame:The legend of good women: The treatise on the Astrolabe: Canterbury tales text. Clarendon press. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- Skeat, Walter William (1906). The prioresses tale, Sire Thopas, the Monkes tale: the Clerkes tale ... from the Canterbury tales. Clarendon Press. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Rev. Prof. Skeat, M.A. with Portrait of Chaucer. 4 vols (1910). "Books on Chaucer". Bohris Standard Library. Retrieved 1 March 2010 – via Internet Archive.

- Stearns, Peter N. The Encyclopedia of world history: ancient, medieval, and modern, p. 240, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001, ISBN 0-395-65237-5

- Rearden, T.H. (1882). The Californian, Volume 5. University of California. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Tatlock, John Strong Perry, The development and chronology of Chaucer's works, Pub. for the Chaucer society, by K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & co., limited, 1907

- Tyrwhitt, Thomas (1860). "Canterbury tales. To which are added an essay on his language and versification, and an introductory discourse, together with notes and a glossary". London: James Nisbet & Co. Retrieved 1 March 2010 – via Internet Archive.

- Wallace, David, Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron, pp. 48, 110–112, Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-521-38851-1

- Ward, Sir Adolphus William, Chaucer, pp. 73–74, MacMillan and Company limited, 1907, University of California

- Warton, Thomas (1871). The history of English poetry, from the close of the eleventh to the commencement of the eighteenth century, Volume II. Princeton University: Reeves and Turner.

- White, William, Notes and queries, Volume 96, p. 284, Oxford University Press, 1897

- anon (1898). "American Society for the Extension of University Teaching". The Citizen. 3. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- anon (December 2004). "Echoes of Boethius and Dante in Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde". Medieval and Early Modern English Studies. 12 (2). Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- anon (1897). Modern language notes, Volume 12 No. 1 – Detailed analysis of Chaucer contact with Petrarch. Johns Hopkins Press: Johns Hopkins University.

- anon (2008). "The World of Chaucer – Medieval Books and Manuscripts: Influences". Glasgow: Special Collections Department, Library, University of Glasgow. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

_-_Petrarch's_house_at_Arqu%C3%A0_-_da_-_Roscoe%2C_Thomas%2C_The_tourist_in_Switzerland_and_Italy_1831.jpg)

.jpg)