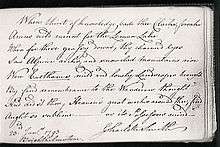

Charlotte Turner Smith

Charlotte Turner Smith (4 May 1749 – 28 October 1806) was an English Romantic poet and novelist. She initiated a revival of the English sonnet, helped establish the conventions of Gothic fiction, and wrote political novels of sensibility. A successful writer, she published ten novels, three books of poetry, four children's books, and other assorted works, over the course of her career. She saw herself as a poet first and foremost, poetry at that period being considered the most exalted form of literature. Scholars now credit her with transforming the sonnet into an expression of woeful sentiment.[1]

During adulthood, Charlotte Smith eventually left husband Benjamin Smith and began writing to support their children. Smith's struggle to provide for her children and her frustrated attempts to gain legal protection as a woman provided themes for her poetry and novels; she included portraits of herself and her family in her novels as well as details about her life in her prefaces. Her early novels are exercises in aesthetic development, particularly of the Gothic and sentimentality. "The theme of her many sentimental and didactic novels was that of a badly married wife helped by a thoughtful sensible lover" (Smith's entry in British Authors Before 1800: A Biographical Dictionary Ed. Stanley Kunitz and Howard Haycraft. New York: H.W. Wilson, 1952. pg. 478.) Her later novels, including The Old Manor House, often considered her best, supported the ideals of the French Revolution.

After 1798, however, Smith's popularity waned and by 1803 she was destitute and ill—she could barely hold a pen, and sold her books to pay off her debts. In 1806, Smith died. Largely forgotten by the middle of the 19th century, her works have now been republished and she is recognized as an important Romantic writer.

Early life

Smith was born on 4 May 1749 in London and baptized on 12 June; she was the oldest child of well-to-do Nicholas Turner and Anna Towers. Her two younger siblings, Nicholas and Catherine Ann, were born within the next five years.[2] Smith received a typical education for a girl in a wealthy family during the late 18th century. Smith's childhood was shaped by her mother's early death (probably in giving birth to Catherine) and her father's reckless spending.[3] After losing his wife, Nicholas Turner travelled and the children were raised by Lucy Towers, their maternal aunt; when exactly their father returned is unknown.[2]

At the age of six, Charlotte went to school in Chichester and took drawing lessons from the painter George Smith. Two years later, she, her aunt, and her sister moved to London and she attended a girls' school in Kensington, where she learned dancing, drawing, music, and acting. She loved to read and wrote poems, which her father encouraged. She even submitted a few to the Lady's Magazine for publication, but they were not accepted.[2]

Marriage and first publication

Nicholas Turner encountered financial difficulties upon his return to England and he was forced to sell some of the family's holdings and to marry the wealthy Henrietta Meriton in 1765. His daughter entered society at the age of twelve, leaving school and being tutored at home. His reckless spending then forced her to marry early. In a marriage that she later described as prostitution, she was given by her father to the violent and profligate Benjamin Smith. On 23 February 1765, at the age of fifteen, she married Benjamin Smith, the son of Richard Smith, a wealthy West Indian merchant and a director of the East India Company. The proposal was accepted for her by her father;[2] forty years later, Smith condemned her father's action, which she wrote had turned her into a "legal prostitute".[3]

Smith's husband fled to France to escape his creditors. She joined him there, until, thanks largely to her, he was able to return to England. Smith's marriage was unhappy, despite having twelve children together. Charlotte joined Benjamin in debtor's prison, where she wrote her first book of poetry, Elegiac Sonnets. Benjamin's father attempted to leave money to Charlotte and her children upon his death, but legal technicalities barred her from acquiring it. She detested living in commercial Cheapside (the family later moved to Southgate and Tottenham) and argued with her in-laws, who she believed were unrefined and uneducated. They, in turn, mocked her for spending time reading, writing, and drawing. Even worse, Benjamin proved to be violent, unfaithful, and profligate. Only her father-in-law, Richard, appreciated her writing abilities, although he wanted her to use them to further his business interests.[3] Richard Smith owned plantations in Barbados and he and his second wife brought five slaves to England, who, along with their descendants, were included as part of the family property in his will. Although Charlotte Smith later argued against slavery in works such as The Old Manor House (1793) and "Beachy Head", she herself benefited from the income and slave labour of Richard Smith's plantations.[2]

In 1766, Charlotte and Benjamin had their first child, who died the next year just days after the birth of their second, Benjamin Berney (1767–77). Between 1767 and 1785, the couple had ten more children: William Towers (born 1768), Charlotte Mary (born c. 1769), Braithwaite (born 1770), Nicholas Hankey (1771–1837), Married Anni Petroose (1779–1843), Charles Dyer (born 1773), Anna Augusta (1774–94), Lucy Eleanor (born 1776), Lionel (1778–1842), Harriet (born c. 1782), and George (born c. 1785). Only six of Smith's children survived her.[2]

Smith assisted in the family business that her husband had abandoned by helping Richard Smith with his correspondence. She persuaded Richard to set Benjamin up as a gentleman farmer in Hampshire and lived with him at Lys Farm from 1774 until 1783.[2] Worried about Charlotte's future and that of his grandchildren and concerned that his son would continue his irresponsible ways, Richard Smith willed the majority of his property to Charlotte's children. However, because he had drawn up the will himself, the documents contained legal problems. The inheritance, originally worth nearly £36,000, was tied up in chancery after his death in 1776 for almost forty years. Smith and her children saw little of it.[2] (It has been proposed that this may have inspired the famous fictional case of interminable legal proceedings, Jarndyce and Jarndyce, in Dickens's Bleak House.[4]) In fact, Benjamin illegally spent at least a third of the legacy and ended up in King's Bench Prison in December 1783. Smith moved in with him and it was in this environment that she wrote and published her first work.[3] Elegiac Sonnets (1784) achieved instant success, allowing Charlotte to pay for their release from prison. Smith's sonnets helped initiate a revival of the form and granted an aura of respectability to her later novels, as poetry was then considered the highest art form. Smith revised Elegiac Poems several times over the years, eventually creating a two-volume work.[3]

Novelist

Novelist

After Benjamin Smith was released from prison, the entire family moved to Dieppe, France to avoid further creditors. Charlotte returned to negotiate with them, but failed to come to an agreement. She went back to France and in 1784 began translating works from French into English. In 1787 she published The Romance of Real Life, consisting of translated selections from François Gayot de Pitaval's trials. She was forced to withdraw her other translation, Manon Lescaut, after it was argued that the work was immoral and plagiarized. In 1786, she published it anonymously.[2]

In 1785, the family returned to England and moved to Woolbeding House near Midhurst, Sussex.[2] Smith's relationship with her husband did not improve and on 15 April 1787, after twenty-two years of marriage, she left him. She wrote that she might “have been contented to reside in the same house with him”, had not “his temper been so capricious and often so cruel” that her “life was not safe”.[5] When Charlotte left Benjamin, she did not secure a legal agreement that would protect her profits—he would have access to them under English primogeniture laws.[2] Smith knew that her children's future rested on a successful settlement of the lawsuit over her father-in-law's will, therefore she made every effort to earn enough money to fund the suit and retain the family's genteel status.[3]

Smith claimed the position of gentlewoman, signing herself "Charlotte Smith of Bignor Park" on the title page of Elegiac Sonnets.[2] All of her works were published under her own name, "a daring decision" for a woman at the time. Her success as a poet allowed her to make this choice.[2] Throughout her career, Smith identified herself as a poet. Although she published far more prose than poetry and her novels brought her more money and fame, she believed poetry would bring her respectability. As Sarah Zimmerman claimed in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, "She prized her verse for the role it gave her as a private woman whose sorrows were submitted only reluctantly to the public."[2]

After separating from her husband, Smith moved to a town near Chichester and decided to write novels, as they would make her more money than poetry. Her first novel, Emmeline (1788), was a success, selling 1500 copies within months. She wrote nine more novels in the next ten years: Ethelinde (1789), Celestina (1791), Desmond (1792), The Old Manor House (1793), The Wanderings of Warwick (1794), The Banished Man (1794), Montalbert (1795), Marchmont (1796), and The Young Philosopher (1798). Smith began her career as a novelist during the 1780s at a time when women's fiction was expected to focus on romance and to foreground "a chaste and flawless heroine subjected to repeated melodramatic distresses until reinstated in society by the virtuous hero".[3] Although Smith's novels employed this structure, they also incorporated political commentary, particularly support of the French Revolution, through the voices of male characters. At times, she challenged the typical romance plot by including "narratives of female desire" or "tales of females suffering despotism".[3] Smith's novels contributed to the development of Gothic fiction and the novel of sensibility.[2]

Smith's novels are autobiographical. While a common device at the time, Antje Blank writes in The Literary Encyclopedia, "few exploited fiction's potential of self-representation with such determination as Smith".[3] For example, Mr. and Mrs. Stafford in Emmeline are portraits of Charlotte and Benjamin.[2] She suffered sorely throughout her life. Her mother died in childbirth when Charlotte was three. Charlotte’s own first child died a day after her second child, Benjamin Berney, was born and Benjamin Berney lived only ten years.The prefaces to Smith's novels told the story of her own struggles, including the deaths of several of her children. According to Zimmerman,"Smith mourned most publicly for her daughter Anna Augusta, who married an émigré...and died aged twenty in 1795."[2] Smith's prefaces positioned her as both a suffering sentimental heroine and a vocal critic of the laws that kept her and her children in poverty.[3]

Smith's experiences prompted her to argue for legal reforms that would grant women more rights, making the case for these reforms through her novels. Smith's stories showed the "legal, economic, and sexual exploitation" of women by marriage and property laws. Initially readers were swayed by her arguments and writers such as William Cowper patronized her. However, as the years passed, readers became exhausted by Smith's stories of struggle and inequality. Public opinion shifted towards the view of poet Anna Seward, who argued that Smith was "vain" and "indelicate" for exposing her husband to "public contempt".[5]

Smith moved frequently due to financial concerns and declining health. During the last twenty years of her life, she lived in: Chichester, Brighton, Storrington, Bath, Exmouth, Weymouth, Oxford, London, Frant, and Elstead. She eventually settled at Tilford, Surrey.[2]

Smith became involved with English radicals while she was living in Brighton from 1791 to 1793. Like them, she supported the French Revolution and its republican principles. Her epistolary novel Desmond tells the story of a man who journeys to revolutionary France and is convinced of the rightness of the revolution and contends that England should be reformed as well. The novel was published in June 1792, a year before France and England went to war and before the Reign of Terror began, which shocked the British public, turning them against the revolutionaries.[2] Like many radicals, Smith criticized the French, but she still endorsed the original ideals of the revolution.[2] In order to support her family, Smith had to sell her works, thus she was eventually forced to, as Blank claims, "tone down the radicalism that had characterised the authorial voice in Desmond and adopt more oblique techniques to express her libertarian ideals".[3] She therefore set her next novel, The Old Manor House (1793), during the American Revolutionary War, which allowed her to discuss democratic reform without directly addressing the French situation. However, in her last novel, The Young Philosopher (1798), Smith wrote a final piece of "outspoken radical fiction".[3] Smith's protagonist leaves Britain for America, as there is no hope for a reform in Britain.

The Old Manor House is "frequently deemed [Smith's] best" novel for its sentimental themes and development of minor characters. Novelist Walter Scott labeled it as such and poet and critic Anna Laetitia Barbauld chose it for her anthology of The British Novelists (1810).[2] As a successful novelist and poet, Smith communicated with famous artists and thinkers of the day, including musician Charles Burney (father of Frances Burney), poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, scientist and poet Erasmus Darwin, lawyer and radical Thomas Erskine, novelist Mary Hays, playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and poet Robert Southey.[2] A wide array of periodicals reviewed her works, including the Anti-Jacobin Review, the Analytical Review, the British Critic, The Critical Review, the European Magazine, the Gentleman's Magazine, the Monthly Magazine, and the Universal Magazine.[2]

Smith earned the most money between 1787 and 1798, after which she was no longer as popular; several reasons have been suggested for the public's declining interest in Smith, including "a corresponding erosion of the quality of her work after so many years of literary labour, an eventual waning of readerly interest as she published, on average, one work per year for twenty-two years, and a controversy that attached to her public profile" as she wrote about the French revolution.[2] Both radical and conservative periodicals criticized her novels about the revolution. Her insistence on pursuing the lawsuit over Richard Smith's inheritance lost her several patrons. Also, her increasingly blunt prefaces made her less appealing to the public.[2]

In order to continue earning money, Smith began writing in less politically charged genres.[3] She published a collection of tales, Letters of a Solitary Wanderer (1801–02) and the play What Is She? (1799, attributed). Her most successful new foray was into children's literature: Rural Walks (1795), Rambles Farther (1796), Minor Morals (1798), and Conversations Introducing Poetry (1804). She also wrote two volumes of a history of England (1806) and A Natural History of Birds (1807, posthumous). She also returned to writing poetry and Beachy Head and Other Poems (1807) was published posthumously.[2] Publishers did not pay as much for these works, however, and by 1803, Smith was poverty-stricken. She could barely afford food and had no coal. She even sold her beloved library of 500 books in order to pay off debts, but feared being sent to jail for the remaining £20.[3]

Illness and death

Smith complained of gout for many years (it was probably rheumatoid arthritis), which made it increasingly difficult and painful for her to write. By the end of her life, it had almost paralyzed her. She wrote to a friend that she was "literally vegetating, for I have very little locomotive powers beyond those that appertain to a cauliflower".[5] On 23 February 1806, her husband died in a debtors' prison and Smith finally received some of the money he owed her, but she was too ill to do anything with it. She died a few months later, on 28 October 1806, at Tilford and was buried at Stoke Church, Stoke Park, near Guildford. The lawsuit over her father-in-law's estate was settled seven years later, on 22 April 1813, more than thirty-six years after Richard Smith's death.[2]

Legacy and Critical Reputation

Stuart Curran, the editor of Smith's poems, has written that Smith is "the first poet in England whom in retrospect we would call Romantic". She helped shape the "patterns of thought and conventions of style" for the period, is responsible for rekindling the sonnet form in England. She influenced popular romantic poets of her time such as, William Wordsworth and John Keats. William Wordsworth, the leading Romantic poet, believed that Smith wrote, "with true feeling for rural nature, at a time when nature was not much regarded by English Poets".[6] He also stated in the 1830s that she was "a lady to whom English verse is under greater obligations than are likely to be either acknowledged or remembered".[7] By the middle of the 19th century, however, Smith was largely forgotten.[8] Not only was Smith respected for her poetry but also for her ten novels, publishing works in a variety of genres. These genres include Gothic, revolutionary, educational, epistolary but always incorporating the novel of sensibility.[9] Although they have yet to receive any type of "critical attention" today, Smith was famous for the publication of her children's books during her writing period.[6] Smith is noted for being one of the most popular poets of her time. One of the first poets to ever receive a salary, Henry James Prye claimed Smith was "[excelled] in two species of composition so different as the novel and the sonnet, and whose powers are so equally capable of charming the imagination, and awakening the passions."[6]

Smith is known for striving to produce her writing at the same level and expectation as Anna Barbauld and famous political economist, Francis Edgeworth. The inspiration she received during the 17th century from these famous writers helped her build an audience and dominate in specific genres. Smith was notorious for not only expressing her personal and emotional struggles but also the anxiety and complications she faced when it came meeting deadlines, mailing out completed volumes, and payment advancements. She was keen in persuading her publishes to work with her issues. Smith would submit final drafts in exchange for "food, lodging, and expenses for her children".[9] Some of the publishers that were willing to negotiate with Smith throughout her career as a writer were Thomas Cadell Sr., Cadell, Jr., and William Davies. Unfortunately she also struggled with disputes from "various booksellers over copyright, a printers competence, or the quality of an engraving for an illustration. She would argue that the time was ripe for a second edition of a novel."[9]

Smith "clung to her own sense of herself as a gentlewoman of integrity,"[9] living by this stand. The negative aspects that Smith claimed to have experienced during the publication process within her career was perceived as self-pity by many publishers of her time, affecting the writer's relationship and reputation with them. Smith’s push to be taken seriously and how she emerges as an essential figure of the “Age of Sensibility” is observed through her powerful use of vulnerability. Antje Blank from The Literary Encyclopedia states, “few exploited fiction’s potential of self-representation with such determination as Smith.” Her work is defined as being "squarely in the cult of sensibility: she believed in the virtue of kindness, in generosity to those less fortunate, and in the cultivation of the finer feelings of sympathy and tenderness for those who suffered needlessly."[9]

Ultimately, ‘Smith’s autobiographical incursions’ bridge the old and the new, ‘older poetic forms and an emerging Romantic voice."[10] Smith was a skillful satirist and political commentator on the condition of England, and this is, I think, the most interesting aspect of her fiction and the one that had most influence on later writers."[10] Onet felt that Smith’s work "rejected an identity defined exclusively by emotionality, matrimony, the family unit, and female sexuality." Overall Smith’s career in writing was rejoiced, well perceived and popular until her later years of living. “Smith deserves to be read not simply as a writer whose work demonstrates changes in taste, but as one of the primary voices of her time and a worthy contemporary of the male romantic poets.”[11]

Smith's novels were republished at the end of the 20th century, and critics "interested in the period's women poets and prose writers, the Gothic novel, the historical novel, the social problem novel, and post-colonial studies" have argued for her significance as a writer.[12] They concluded that she helped to revitalize the English sonnet, a view found in Coleridge and others. Scott wrote that she "preserves in her landscapes the truth and precision of a painter" and poet and Barbauld claimed that Smith was the first to include sustained natural description in novels.[12] In 2008, Smith's complete prose became available to the general public. The edition contains all her novels, the children's stories and rural walks.[13]

Literary Circle

Smith's novels were read and critiqued by her friends who were also writers, as she would return the favor, they found it beneficial to improve and encourage each other's work; Ann Radcliffe, who also wrote novels in Gothic fiction was among these friends. Along with praise, Smith also received backlash from other famous writers. "Jane Austen - though she ridiculed Smith's novels, actually borrowed plot, character, and incident from them."[9] Educational writer John Bennet wrote that "the little sonnets of Miss Charlotte Smith are soft, pensive, sentimental and pathetic, as a woman's productions should be. The muses, if I mistake not, will, in time, raise her to a considerable eminence. She has, as yet, stepped forth only in little things, with a diffidence that is characteristic of real genius in its first attempts. Her next public entre may be more in style, and more consequential."[14] Smith is never too specific about her republicanism; her ideas are based off the scholars Rousseau, Voltaire Diderot, Montesquieu, and John Locke.[11] "Charlotte Smith tried not to swim too strongly against the current of public view, because she needed to sell her novels in order to provide for her children".[10]

Poet and contributor to beginning of the Romanticist movement, Robert Southey, also sympathized with Smith’s hardships. Southey even says, "[although] she has done more and done better than other women writers, it has not been her whole employment — she is not looking out for admiration and talking to show off."[6] In addition to Jane Austen, Henrietta O’Neill, Reverend Joseph Cooper Walker, and Sarah Rose were also people Smith considered trusted friends. After becoming famous for marrying in a great Irish home, Henrietta O'Neill, similar to Austen provided Smith "with a poetic, sympathetic friendship and with literary connections."[9] Henrietta helped her gain an "entry into a fashionable, literary world to which she otherwise had little access; here she almost certainly met, Dr. Moore (author of A View of Society and Manners in Italy and Zeluco) and Lady Londonderry, among others.[9]

One of Smith's longest friends and respected mentors in the business was with Reverend Joseph Cooper Walker, an antiquarian and writer of Dublin. "Walker handled her dealings with John Rice, who published Dublin editions of many of her works. She confided openly in Walker about literary and familial matters."[9] Through the publication of personal letters Smith sent to close companion Sarah Rose, readers are shown a much more positive and joyful side to Smith. Although today his writing is seen as mediocre, William Hayley, another friend of Smith's was "liked, respected, influential" during their time, especially because he was offered laureateship upon the death of Thomas Warton."[9] As time went on Hayley Smith withdrew his support from her in 1794 and corresponded with her infrequently after that. Smith perceived Hayley's actions as betrayal; he would often make claims that she was a “Lady of signal sorrows, signal woes." Even with her success as a writer and handful of accredited friends throughout her lifetime Smith was "sadly isolated from other writers and literary friends"[9] Although many believed Hayley’s statements to be true many people believed Smith was a "woman of signal achievement, energy, ambition, devotion, and sacrifice. Her children and her literary career evoked from her best efforts, and did so in about equal measure."[9]

Selected works

Poetry

- Elegiac Sonnets (1784)

- The Emigrants (1793)

- Beachy Head and Other Poems (1807)

Novels

- Emmeline; or The Orphan of the Castle (1788)

- Ethelinde; or the Recluse of the Lake (1789)

- Celestina (1791)

- Desmond (1792)

- The Old Manor House (1793)

- The Wanderings of Warwick (1794)

- The Banished Man (1794)

- Montalbert (1795)

- Marchmont (1796)

- The Young Philosopher (1798)

Educational works

- Rural Walks (1795)

- Rambles Farther (1796)

- Minor Morals (1798)

- Letters Of A Solitary Wanderer (1800)

- Conversations Introducing Poetry (1804)

Notes

- ↑ ed, M. H. Abrams, general (2012). The Norton anthology of English literature (9th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-393-91248-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Zimmerman

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Blank.

- ↑ Jacqueline M. Labbe, ed. The Old Manor House by Charlotte Turner Smith, Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2002 ISBN 978-1-55111-213-8, Introduction p. 17, note 3.

- 1 2 3 Qtd. in Blank.

- 1 2 3 4 "Commentary: William Wordsworth on Charlotte Smith". spenserians.cath.vt.edu. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- ↑ Quoted in Zimmerman.

- ↑ Curran, xix.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Stanton, Judith (2003). "The Collected Letters of Charlotte Smith". eds.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.library.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- 1 2 3 Onet, Alina-Elena (May 1, 2015). "The Spirit of the Age".

- 1 2 Fry, Carrol (1996). Charlotte Smith. New York: Twayne.

- 1 2

- ↑ The Works of Charlotte Smith. Volumes I-V by Charlotte Smith; Stuart Curran; Michael Gamer; Judith Stanton; Kristina Straub. Review by Gary Kelly, Keats-Shelley Journal Vol. 56, (2007), pp. 222–224. Published by: Keats-Shelley Association of America, Inc. Article Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30210585

- ↑ John Bennet, Letters to a young Lady. American Museum [Philadelphia] (January 1792) 11.

Bibliography

- Blank, Antje. "Charlotte Smith" (subscription only). The Literary Encyclopedia. 23 June 2003. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- Craciun, Adriana. British Women Writers and the French Revolution: Citizens of the World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. ISBN 1-4039-0235-6.

- Curran, Stuart. "Introduction". The Poems of Charlotte Smith. Women Writers in English 1350–1850. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-19-508358-X.

- Fry, Carrol Lee. Charlotte Smith. New York: Twayne, 1996. ISBN 0-8057-7046-1.

- Goodman, Kevis. "Conjectures on Beachy Head: Charlotte Smith’s Geological Poetics and the Ground of the Present." ELH 81.3 (2014): 983-1006.

- Hart, Monica Smith. "Charlotte Smith's Exilic Persona." Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas. 8.2 (2010): 305-323.

- Hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic Feminism: The Professionalization of Gender from Charlotte Smith to the Brontes. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998. ISBN 0-271-03361-4.

- Keane, Angela. Women Writers and the English Nation in the 1790s: Romantic Belongings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-02240-1.

- Kelley, Theresa M. Clandestine Marriage: Botany and Romantic Culture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. ISBN 1-421-40517-2.

- Kelley, Theresa M. “Romantic Histories: Charlotte Smith and Beachy Head,” Nineteenth-Century Literature 59:3 (2004): 281-314.

- Klekar, Cynthia. “The Obligations of Form: Social Practice in Charlotte Smith’s Emmeline.” Philological Quarterly 86, no. 3 (2007): 269-89.

- Labbe, Jacqueline M. Charlotte Smith: romanticism, poetry, and the culture of gender. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-7190-6004-4.

- Labbe, Jacqueline M., ed. Charlotte Smith in British Romanticism. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2008. ISBN 1-851-96945-4.

- Pascoe, Judith. “Female Botanists and the Poetry of Charlotte Smith.” Re-Visioning Romanticism: British Women Writers, 1776–1837 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994), 193-209. ISBN 0-812-21421-8.

- Pascoe, Judith. Romantic Theatricality: Gender, Poetry, and Spectatorship. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-801-43304-5.

- Pinch, Adela. Strange Fits of Passion: Epistemologies of Emotion, Hume to Austen. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Scarth, Kate. "Elite Metropolitan Culture, Women, and Greater London in Charlotte Smith's Emmeline and Celestina." European Romantic Review 25.5 (2014): 629-48.

- Sodeman, Melissa. Sentimental Memorials: Women and the Novel in Literary History. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014. ISBN 0-804-79132-5.

- Zimmerman, Sarah M. "Smith, Charlotte". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25790. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charlotte Turner Smith. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Charlotte Turner Smith |

- Charlotte Smith at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

- Works by Charlotte Turner Smith at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charlotte Turner Smith at Internet Archive

- Works by Charlotte Turner Smith at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Jacqueline Labbe (Warwick University) talks about the life and works of Charlotte Turner Smith (Part 1) on YouTube

- Jacqueline Labbe (Warwick University) talks about the life and works of Charlotte Turner Smith (Part 2) on YouTube

- Jacqueline Labbe (Warwick University) talks about the life and works of Charlotte Turner Smith (Part 3) on YouTube

- Charlotte Smith at Library of Congress Authorities, with 37 catalogue records (mainly under 'Smith, Charlotte Turner')

- Complete Poetical Works of Charlotte Smith at Delphi Classics

- Works

| Library resources about Charlotte Turner Smith |

| By Charlotte Turner Smith |

|---|

- Selected works of Smith at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln

- Elegiac Sonnets (1827) at the British Women Romantic Poets Project

- "The Emigrants" (1793) at the British Women Romantic Poets Project

- Beachy Head; With Other Poems (1807) at the British Women Romantic Poets Project

- The Old Manor House (1793) at A Celebration of Women Writers

- Letters of a Solitary Wanderer (1802) at the Internet Archive

- Rural Walks (1795 at the Internet Archive

- Emmeline (1789, third edition), Vol. 1, Vol. 2 Vol. 3, and Vol. 4 at Internet Archive

- Ethelinde (1789) at Internet Archive

- Celestina (1791, second edition), Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, and Vol.4 at Internet Archive

- Wanderings of Warwick (1794) at Internet Archive

- Montalbert (1795) at Internet Archive

- Marchmont (1796) at Internet Archive

- The Young Philosopher (1798) at Google Books