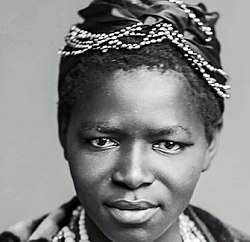

Charlotte Maxeke

Charlotte Makgomo (née Mannya) Maxeke (7 April 1874[1] – 16 October 1939) was a South African religious leader, social worker and political activist.

Personal life

Charlotte Makgomo (née Mannya) Maxeke was born in Ga-Ramokgopa village in the Polokwane (Pietersburg) District, Limpopo province on April 7 1874. She was the daughter of John Kgope Mannya, the son of headman Modidima Mannya from Batlokwa people, under Chief Mamafa Ramokgopa and Anna Manci, a Xhosa woman from Fort Beaufort, Eastern Cape.[2] Charlotte's father was a roads foreman and Presbyterian lay preacher, and her mother a teacher.[3] Soon after her birth, Charlotte's family moved to Fort Beaufort, where her father had gained employment at a road construction company.[2] Details about Charlotte siblings are unclear, however she had a sister known as Katie, who was born in Fort Beaufort.[4] The date and place of birth of Charlotte Maxeke is often contested ranging from 1871, 1872 to 1874. The Home Affairs minister of South Africa, Naledi Pandoor took special interest in this detail of Charlotte Maxeke's life however, no records were found. The date in 1871 is also often accepted as it does not conflict with the age of her younger sister Katie who was born in 1873.[5]

At age 8, she began her primary school classes at a missionary school taught by the Reverend Isaac Williams Wauchope in Uitenhage. She excelled in Dutch and English, mathematics and music. She spent long hours tutoring her less skilled classmates, often with great success. Reverend Wauchope credited Charlotte with much of his teaching success particularly with regard to languages. Maxeke's musical prowess was visible at a young age. Describing Charlotte's singing Rev. Henry Reed Ngcayiya, a minister of the United Church and family friend said: "She had the voice of an angel in heaven."[6]

From Uitenhage, Charlotte moved to Port Elizabeth to study at the Edward Memorial School under Headmaster Paul Xiniwe. Charlotte excelled and completed her secondary school education in record time, achieving the highest possible grades. In 1885, after the discovery of diamonds, Charlotte moved to Kimberley, Northern Cape with her family.[6] In 1903 she married fellow Wilberforce University graduate, Dr. Marshall Maxeke, a Xhosa born on 1 November 1874 at Middledrift. The couple lost a child prior to their marriage, and did not have any children thereafter.[7] Charlotte died in 1939 Johannesburg, Gauteng at the age of 65.[6]

Foreign travel

After arriving in Kimberley, Northern Cape in 1885, Charlotte began teach fundamentals of indigenous languages to expatriates and basic English to African "boss-boys". However, it was music that soon changed her fortunes. Charlotte and her sister Katie joined the African Jubilee Choir in 1891. Her talent attracted the attention of Mr. K. V. Bam, a local choir master who was organising an African choir to tour Europe. Charlotte's rousing success after her first solo performance in Kimberley Town Hall immediately resulted in her appointment to the Europe-bound choir operation, which was taken over from Mr. Bam by a European. The group left Kimberley in early 1896 and sang to numerous audiences in major cities of Europe. Command royal performances, including one at Queen Victoria's 1897 Jubilee at London's Royal Albert Hall, added to their mounting prestige. At the conclusion of the European tour, the choir toured North America. The choir managed to sell out venues in the Canada and the United States.[6]

At the completion of the tour of the United States, the European organiser, without paying a single member of the choir, deserted it with all the funds and travel tickets, and could not be found. Charlotte and the other choir members were left stranded and penniless on the streets of New York City. The story of the stranded African singers quickly appeared in newspapers across the United States. Americans soon offered financial assistance to the choir. Bishop Daniel A. Payne, of the African Methodist Church (AME) in Ohio, a former missionary in the Cape, recognised Charlotte's name in the newspaper. He contacted her and offered her a church scholarship to Wilberforce University, the AME Church University in Xenia, Ohio, in US. Charlotte accepted the offer. At the university, she was taught under Pan-Africanist, W.E.B Du Bois.[6] After obtaining her BSC degree from the Wilberforce University in 1901, she became the first black South African woman to earn a degree.[8]

Political activism

Charlotte became politically active while in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, in which she played a part in bringing to South Africa. The church later elected her president of the Women's Missionary Society. By 1919 she was active in the anti-pass laws demonstrating which led her to found the Bantu Women's League which later became part of the African National Congress Women's League.[9] Charlotte attended the launch of the South African Native National Congress in Bloemfontein in 1912. At this point, her concerns were mostly related to churches and their social issues. Charlotte used to write about the political as well as social issues that women face in isiXhosa. In the writing piece "Umteteli wa Banti" she wrote about these specific issues. She founded the Bantu Women's League of the SANNC in 1918. During her term in leadership of the Bantu Women's League, she led a delegation to the then South African Prime Minister, Louis Botha, to discuss the issues with passes for women. These discussions resulted in a protest against passes for women the following year. She addressed an organisation for he voting rights of women called Women's Reform Club in Pretoria and further joined the council of Europeans and Bantu's. Maxeke was elected as the president of the Women's missionary society. Maxeke participated with protests related to low wages at Witwatersrand and eventually joined the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union in 1920. She continued to be involved in many multiracial groups fighting against the Apartheid System and for women's rights. In 1928, Maxeke set up an employment agency for Africans in Johannesburg. She did this after attending a conference in the USA where she grew even more concerned for the welfare of African people. She later became the first black woman to be employed as a parole officer for juvenile delinquents.[10]

Legacy

Maxeke's name has been given to the former "Johannesburg General Hospital" which is now known as the "Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital". The South African Navy submarine SAS Charlotte Maxeke was named after her.[11] Maxeke is often honoured as the "Mother of Black Freedom in South Africa". There is an ANC nursery school named after Charlotte Maxeka.[12] At an event in 2015 dedicated to International Women's Day at Kliptown's Walter Sisulu Square, the Gauteng Infrastructure Development MEC plans to convert Maxeke's home into a museum and interpretation centre.[13]

German engineers referred to 3 South African submarines as "heroine class". These submarines were named after three powerful south African women namely, S101 (named after SAS Manthatisi, a female warrior of the Chief of the Batlokwa tribe), S102 (named after Charlotte Maxeke) and S103 (named after the South African rain queen SAS Modjaji) [14] The ANC also hosts an annual Charlotte Maxeke Memorial Lecture.[15] Beatrice Street in Durban was changed to Charlotte Maxeke Street in her honour.[16][17] Maitland Street in Bloemfontein was renamed Charlotte Maxeke Street in honour of her contribution to South Africa.[18]

See also

References

- Songs of Zion - The African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States and South Africa, James T. Campbell, 1995, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Jaffer, Zubeida (8 September 2016). "Heralded heroine: Why is Charlotte Maxeke's life such a blurry memory for SA?". Analysis. Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- 1 2 "The Life and Legacy of Charlotte Manye-Maxeke". Parliament of South Africa. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ↑ "Charlotte Maxeke". Ethekwini Municipality. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ↑ "Charlotte (née Manye) Maxeke". South African History Online. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ↑ https://mg.co.za/article/2016-09-08-00-heralded-heroine-why-is-charlotte-maxekes-life-such-a-blurry-memory-for-sa/ Accessed 2 December 2017

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A tribute: Dr. Charlotte Manye Maxeke 7 April 1874 - 16 October 1939". South African History Online. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ↑ "Charlotte Maxeke still inspires today". News 24. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ↑ "Inspirational African Women: Charlotte Mannya Maxeke". Solutions 4 Africa. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ↑ Why is ANCWL still backing Zuma? IOL

- ↑ http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/charlotte-n%C3%A9e-manye-maxeke Accessed 2 December 2017

- ↑ Lekota, M. G. P. (26 April 2007). "Welcoming of SAS Charlotte Maxeke". gov.za. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/charlotte-n%C3%A9e-manye-maxeke Accessed 2 December 2017

- ↑ https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/south-africa-fast-facts/history-facts/maxeke-gauteng-090315 Accessed 2 December 2017

- ↑ https://mg.co.za/article/2016-09-08-00-heralded-heroine-why-is-charlotte-maxekes-life-such-a-blurry-memory-for-sa/ Accessed 2 December 2017

- ↑ https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/opinion/columnists/2012-08-07-a-legacy-for-sa-women/ Accessed 2 December 2017

- ↑ https://mg.co.za/article/2012-08-04-ancwl-praises-maxeke-for-helping-to-empower-woman Accessed 3 December 2017

- ↑ https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/south-africa-fast-facts/history-facts/maxeke-gauteng-090315 Accessed 2 December 2017

- ↑ https://mg.co.za/article/2012-08-04-ancwl-praises-maxeke-for-helping-to-empower-woman Accessed 3 December 2017