Cannabis in California

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

|

Chemistry |

|

Economics |

|

Regional

|

|

Cannabis in California is legal for both medical and recreational use. In recent decades, the state has been at the forefront of efforts to reform cannabis laws, beginning in 1972 with the nation's first ballot initiative attempting to legalize cannabis. Although Proposition 19 was unsuccessful, California would later become the first state to legalize medical cannabis with the passage of the Compassionate Use Act of 1996 (Proposition 215).[1] In November 2016, California voters approved the Adult Use of Marijuana Act (Proposition 64) to legalize the recreational use of cannabis.

California's main regulatory agencies are the Bureau of Cannabis Control (BCC), Department of Food and Agriculture, Department of Public Health and Cannabis Regulatory Authority (CRA).[2][3]

History

Industrial hemp

Cannabis was cultivated for fiber and rope as early as 1795 in California, when cultivation began at Mission San Jose under the governorship of Diego de Borica. Cannabis was grown in several regions of Southern California, with two-thirds of it being grown on the missions.[4] California produced 13,000 pounds of hemp in 1807, and 220,000 pounds in 1810.[5] However, in 1810 Mexico began to rebel against the Spanish crown, and the subsidies for growing hemp were cut, leading to a near-disappearance of the crop. A few missions continued to grow it for local use, and the Russian colonists grew hemp at Fort Ross until the station was abandoned in 1841.[4]

Psychoactive cannabis

Among the early cultivators of cannabis for recreational use in California were Arabs, Armenians, and Turks who grew cannabis as early as 1895 to make hashish for local consumption.[6] Unlike in other states where fears of black or Hispanic use of cannabis drove new restrictions, California was an exception for its focus on South Asian immigrants. A California delegate to the Hague Convention wrote in 1911: Within the last year we in California have been getting a large influx of Hindoos and they have in turn started quite a demand for cannabis indica; they are a very undesirable lot and the habit is growing in California very fast.[7]

Criminalization

The Poison Act was passed in California in 1907, and in 1913 an amendment[8] was made to make possession of "extracts, tinctures, or other narcotic preparations of hemp, or loco-weed, their preparations and compounds" a misdemeanor.[9] There is no evidence that the law was ever used or intended to restrict pharmaceutical cannabis; instead it was a legislative mistake, and in 1915 another amendment[10] forbade the sale or possession of "flowering tops and leaves, extracts, tinctures and other narcotic preparations of hemp or loco weed (Cannabis sativa), Indian hemp" except with a prescription.[9] Both bills were drafted and supported by the California State Board of Pharmacy.[9]

In 1914, one of the first cannabis drug raids in the nation occurred in the Mexican-American neighborhood of Sonoratown in Los Angeles, where police raided two "dream gardens" and confiscated a wagonload of cannabis.[11] In 1925, possession, which had previously been treated the same as distribution, became punishable by up to 6 years in prison, and black market sale, which had initially been a misdemeanor punishable by a $100–$400 fine and/or 50–180 days in jail for first offenders, became punishable by 6 months–6 years.[9] In 1927, the laws designed to target opium usage were finally extended to Indian hemp.[9] In 1929, second offenses for possession became punishable by sentences of 6 months–10 years.[9] In 1937, cannabis cultivation became a separate offense.[9]

By 1932, 60% of narcotics arrests in Los Angeles involved cannabis, which was considered "much less serious than the morphine cases."[12] In 1954, penalties for marijuana possession were hiked to a minimum 1–10 years in prison, and sale was made punishable by 5–15 years with a mandatory 3 years before eligibility for parole; two prior felonies raised the maximum sentences for both offenses to life imprisonment.[9]

Popularization

In the 1950s and 1960s, the beatnik and later hippie cultures experimented with cannabis, driving increased interest in the drug. In 1964, the first cannabis legalization group was formed in the U.S. when Lowell Eggemeier of San Francisco was arrested, and his attorney established LEMAR (LEgalize MARijuana) shortly afterwards.[13] By the mid-1960s, the Saturday Evening Post was publishing articles estimating that half the college population of California had tried cannabis. One writer commented that usage was: so widespread that pot must be considered an integral part of the generation's life experience.[14]

Illicit cultivation

In the 1960s–1970s, people in California had developed the sinsemilla ("without seeds") method of producing cannabis, uprooting the male plants before they could pollinate the females, resulting a seedless and more potent cannabis. Around 1975, this technique arrived in Humboldt County, which was to become one of the nation's most famous centers of cannabis production. California growers received an unintentional advantage from the US government, which in the 1970s began spraying cannabis fields in Mexico with the herbicide paraquat. Fears of contamination led to a drop in demand for cheaper Mexican cannabis, and a corresponding increase in demand for California-grown cannabis. By 1979, 35% of cannabis consumed in California was grown in-state. By 2010, 79% of cannabis nationwide came from California.[15]

Decriminalization

Moscone Act (1975)

Decriminalization of marijuana, which treats the possession of small amounts of the drug as a civil, rather than a criminal, offense, was established in July 1975 when the Legislature passed Senate Bill 95, the Moscone Act.[9][16][17][18] SB 95 made possession of one ounce (28.5 grams) of marijuana a misdemeanor punishable by a $100 fine,[19] with higher punishments for amounts greater than one ounce, for possession on school grounds, or for cultivation.[20]

Proposition 36 (2000)

Proposition 36 (also known as the Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act of 2000) was approved by 61% of voters, requiring that "first and second offense drug violators be sent to drug treatment programs instead of facing trial and possible incarceration."[21]

Senate Bill 1449 (2010)

On September 30, 2010, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed into law CA State Senate Bill 1449, which further reduced the charge of possession of one ounce of cannabis or less, from a misdemeanor to an infraction, similar to a traffic violation—a maximum of a $100 fine and no mandatory court appearance or criminal record.[22] The law became effective January 1, 2011.

Medical cannabis legalization

Early reform efforts (pre-1996)

The movement to legalize medical cannabis sprang out of San Francisco in the early 1990s, with efforts soon spreading statewide and eventually across the nation. In November 1991, 79% of the San Francisco voters approved Proposition P, which called on state lawmakers to pass legislation allowing the medical use of cannabis.[23] Additionally, the city board of supervisors passed a resolution in August 1992 urging the police commission and district attorney to "make lowest priority the arrest or prosecution of those involved in the possession or cultivation of [cannabis] for medicinal purposes" and to "allow a letter from a treating physician to be used as prima facia evidence that marijuana can alleviate the pain and suffering of that patient's medical condition".[24] The resolution allowed the open distribution of cannabis to AIDS patients and others throughout the city, most notably through the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club which was operated by medical cannabis activist Dennis Peron (who spearheaded Proposition P and later the statewide Proposition 215).[25] Similar clubs appeared outside San Francisco in the ensuing years as other cities passed legislation to support the medical use of cannabis. The Wo/Men's Alliance for Medical Marijuana was founded in 1993 after 75% of Santa Cruz voters approved Measure A in November 1992.[26] And the Oakland Cannabis Buyers' Cooperative was founded in 1995 shortly before the city council passed multiple medical cannabis resolutions.[26]

Following the lead of San Francisco and other cities in California, state lawmakers passed Senate Joint Resolution 8 in 1993, a non-binding measure calling on the federal government to enact legislation allowing physicians to prescribe cannabis.[27] In 1994, Senate Bill 1364 was approved by state legislators, to reclassify cannabis as a Schedule II drug at the state level.[27] And Assembly Bill 1529 was approved in 1995, to create a medical necessity defense for patients using cannabis with a physician's recommendation, for treatment of AIDS, cancer, glaucoma, or multiple sclerosis.[27] Both SB 1364 and AB 1529 were vetoed by Governor Pete Wilson, however, paving the way for the passage of Proposition 215 in 1996.[27]

Proposition 215 (1996)

Frustrated by vetoes of medical cannabis bills in successive years, medical cannabis advocates in California took the issue directly to the voters, collecting 775,000 signatures for qualification of a statewide ballot initiative in 1996.[28] Proposition 215 – the Compassionate Use Act of 1996 – was subsequently approved with 56% of the vote, legalizing the use, possession, and cultivation of cannabis by patients with a physician's recommendation, for treatment of cancer, anorexia, AIDS, chronic pain, spasticity, glaucoma, arthritis, migraine, or "any other illness for which marijuana provides relief".[29] The law also allowed patient caregivers to cultivate cannabis, and urged lawmakers to facilitate the "safe and affordable distribution of marijuana".[29]

Senate Bill 420 (2003)

Vague wording became a major criticism of Prop. 215, though the law has since been clarified through California Supreme Court rulings and the passage of subsequent laws. The first solution of this came by legislation that established statewide guidelines for Proposition 215 by Senate Bill 420 in January 2003. To differentiate patients from non-patients, Governor Gray Davis signed California Senate Bill 420 (colloquially known as the Medical Marijuana Program Act) in 2003, establishing an identification card system for medical marijuana patients. SB 420 also allows for the formation of patient collectives, or non-profit organizations, to provide the drug to patients.

In 2006 San Diego County filed a lawsuit over its required participation in the state ID card program,[30] but the challenge was later struck down and the city was forced to comply.[31] In January 2010 the California Supreme Court ruled in People v. Kelly that SB 420 did not limit the quantity of cannabis that a patient can possess. All possession limits were therefore lifted.

Recreational cannabis legalization

Proposition 19 (1972)

In 1972, California became the first state to vote on a ballot measure seeking to legalize cannabis. Proposition 19 – the California Marijuana Initiative – sought to legalize the use, possession, and cultivation of cannabis, but did not allow for commercial sales.[16] The initiative was spearheaded by the group Amorphia, which was founded in 1969 (by Blair Newman) and financed its activities through the sale of hemp rolling papers.[32] It was ultimately defeated by a wide margin (33–67%), but supporters were encouraged by the results,[33] which provided momentum to other reform efforts in California in subsequent years.[26] In 1974, Amorphia ran into financial difficulties and became the California chapter of NORML.[34]

Marijuana Control, Regulation, and Education Act (2009)

In February 2009, Tom Ammiano introduced the Marijuana Control, Regulation, and Education Act, which would remove penalties under state law for the cultivation, possession, and use of marijuana for persons the age of 21 or older. When the Assembly Public Safety Committee approved the bill on a 4 to 3 vote in January 2010, this marked the first time in United States history that a bill legalizing marijuana passed a legislative committee. While the legislation failed to reach the Assembly floor, Ammiano stated his plans to reintroduce the bill later in the year, depending on the success of Proposition 19, the Regulate, Control and Tax Cannabis Act.[35] According to Time, California tax collectors estimated the bill would have raised about $1.3 billion a year in revenue.

Critics such as John Lovell, lobbyist for the California Peace Officers' Association, argued that too many people already struggle with alcohol and drug abuse, and legalizing another mind-altering substance would lead to a surge of use, making problems worse.[36] Apart from helping the state's budget by enforcing a tax on the sale of cannabis, proponents of the bill argued that legalization would reduce the amount of criminal activity associated with the drug.

Proposition 19 (2010)

In November 2010, California voters rejected Proposition 19 (by a vote of 53.5% to 46.5%), an initiative that would have legalized the use, possession, and cultivation of cannabis for adults age 21 and over, and regulated its sale similar to alcohol.[37] The initiative faced stiff opposition from numerous police organizations in the state, while many growers in the Emerald Triangle were strongly opposed due to fears that corporate megafarms would put them out of business.[31] The initiative was also undercut by the passage of Senate Bill 1449 a month before the election.[31] Proposition 19 was spearheaded by Richard Lee, founder of Oaksterdam University.[31]

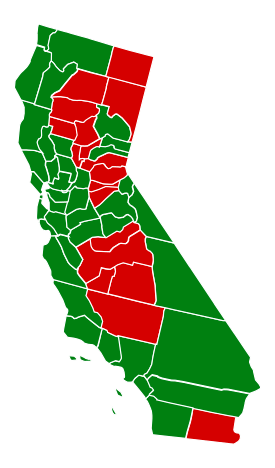

Proposition 64 (2016)

On November 8, 2016, Proposition 64, also known as the Adult Use of Marijuana Act, passed by a vote of 57% to 43%, legalizing the sale and distribution of cannabis in both a dry and concentrated form. Adults are allowed to possess up to one ounce of cannabis for recreational use and can grow up to six live plants individually or more commercially with a license.

Licenses will be issued for cultivation and business establishment beginning in 2018. In 2016, in response to Proposition 64, State Treasurer John Chiang set up a working group to explore access to financial services for legal marijuana-related businesses operating in California,[38] as access to banking services has been a problem due to the additional burdens mandated by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) on financial institutions to assure that any marijuana related business clients are in compliance with all state laws.[39] In January, 2018, Los Angeles had no licensed retailers; the closest cities with licensed retail sales were Santa Ana on January 1 and West Hollywood on January 2.[40][41]

Legality

Medical usage

California was the first state to establish a medical marijuana program, enacted by Proposition 215 in 1996 and Senate Bill 420 in 2003. Prop. 215, also known as the Compassionate Use Act allows people the right to obtain and use cannabis for any illness if they obtain a recommendation from a doctor. California's Supreme Court has ruled there are no specified limits as to what a patient may possess in their private residence if the cannabis is strictly for the patient's own use.[42] Medical cannabis identification cards are issued through the California Department of Public Health's Medical Marijuana Program (MMP). The program began in three counties in May 2005, and expanded statewide in August of the same year. 37,236 cards have been issued throughout 55 counties as of December 2009. However, cannabis dispensaries within the state accept recommendations, with an embossed license, from a doctor who has given the patient an examination and believes cannabis would be beneficial for their ailment.

Critics of California's medical cannabis program argued that the program essentially gave cannabis quasi-legality, as "anyone can obtain a recommendation for medical marijuana at any time for practically any ailment".[43] Acknowledging that there were instances in which the system was abused and that laws could be improved, Stephen Gutwillig of the Drug Policy Alliance insisted that what Proposition 215 had accomplished was "nothing short of incredible".[43] Gutwillig argued that because of the law, 200,000 patients in the state had safe and affordable access to medical cannabis to relieve pain and treat medical conditions, without having to risk arrest or buy off the black market.[43]

Conflict with federal law

Although Proposition 215 legalized medical cannabis in California, at the federal level it remained a Schedule I prohibited drug. Seeking to enforce this prohibition, the Justice Department conducted numerous raids and prosecutions of medical cannabis providers throughout the state in subsequent years. Some state and local officials strongly supported these enforcement efforts, in particular Attorney General Dan Lungren who was a vocal opponent of Proposition 215 leading up to its passage.[31] Other officials, such as San Francisco District Attorney Terence Hallinan, condemned the actions as a gross intrusion into the state's affairs.[31] The raids and prosecutions increased in frequency throughout the Bush and Obama years,[44] until finally in December 2014 the Rohrabacher–Farr amendment was enacted at the federal level.

Of particular note was a raid that occurred at the Wo/Men's Alliance for Medical Marijuana in Santa Cruz in September 2002. WAMM was a non-profit collective set up to provide cannabis to seriously ill patients, and was working closely with local authorities to follow all applicable state and local laws.[45] On the morning of September 5, DEA agents decked out in paramilitary gear and semiautomatic weapons stormed the premises, destroyed all the cannabis plants, and arrested the property owners Mike and Valerie Corral.[31][46] This prompted an angry response from nearby medical cannabis patients – some in wheelchairs – who gathered at the site to block federal agents from leaving, until finally after three hours later the Corrals were released.[31] The raid triggered a strong backlash from Santa Cruz officials as well, who sanctioned an event two weeks later where cannabis was handed out to patients on the steps of city hall,[47] attracting widespread media attention.[26] The DEA was "appalled" by the event,[48] but took no further action.

Further pushback against federal enforcement efforts occurred in June 2003 following the jury trial conviction of Ed Rosenthal, who had been raided by the DEA in 2002 for growing more than 100 cannabis plants in an Oakland warehouse.[49] Because cannabis remained a prohibited substance under federal law, jurors could not be informed that Rosenthal had been deputized by the city of Oakland to grow the cannabis, or even that the cannabis was being used for medical purposes only.[31] Rosenthal was easily convicted as a result; however, immediately following the trial, when jurors found out the true circumstances of the case, they publicly renounced the verdict they had just handed down and demanded a retrial.[31] Judge Charles Breyer, in part influenced by the extraordinary action of the jurors, sentenced Rosenthal to just one day in jail, of which he had already served.[49]

In July 2007, a new tactic was adopted by the DEA of threatening landlords renting to medical cannabis providers.[50] Letters were sent to a number of property owners in the Los Angeles area, informing them that they faced up to 20 years in prison for violating the "crack house statute" of the Controlled Substances Act, in addition to seizure of their properties. This tactic subsequently spread to other areas of California, while DEA raids continued to increase as well in the following years. In October 2011 an extensive and coordinated crackdown on California's cannabis dispensaries was announced by the chief prosecutors of the state's four federal districts.[51]

Three major court cases originated in California that attempted to challenge the federal government's ability to enforce federal law in medical cannabis states.[52] Conant v. McCaffrey was a case brought forth by a group of California doctors and patients. Decided in 2000, it upheld the right of physicians to recommend but not prescribe cannabis. In United States v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers' Cooperative (2001), it was argued that medical use of cannabis should be permitted as constituted by a "medical necessity" – but this argument was unsuccessful. In Gonzales v. Raich (2005), the constitutionality of the Controlled Substances Act was challenged based on the idea that cannabis grown and consumed in California does not qualify as interstate commerce – but this argument was also unsuccessful.

Recreational cannabis

Recreational usage of marijuana is legal under Proposition 64. Immediately upon certification of the November 2016 ballot results, adults age 21 or older were allowed to:

- Possess, transport, process, purchase, obtain, or give away, without any compensation whatsoever, no more than one ounce of dry cannabis or eight grams concentrated cannabis to adults the age of 21 or older.

- Possess, plant, cultivate, harvest, dry, or process no more than six live plants and the produce of those plants in a private residence, in a locked area not seen from normal view, in compliance with all local ordinances.

- Smoke or ingest cannabis.

- Possess, transport, purchase, obtain, use, manufacture, or give away marijuana paraphernalia to peoples the age of 21 or older.

Users may not:

- Smoke it where tobacco is prohibited.

- Possess, ingest or smoke within 1,000 feet of a day care, school, or youth center while children are present (except within a private residence and if said smoke is not detectable to said children).

- Manufacture concentrated cannabis using a volatile solvent without a license under Chapter 3.5 of Division 8 or Division 10 of the Business and Professions Code.

- Possess an open container or marijuana paraphernalia while in the driver or passenger seat of a vehicle used for transportation.

- Smoke or ingest marijuana while operating a vehicle used for transportation.

- Smoke or ingest marijuana while riding in the passenger seat or compartment of a vehicle.[53]

Legal sales for non-medical use are allowed by law beginning January 1, 2018, following formulation of new regulations on retail market by the state's Bureau of Medical Cannabis Regulation (to be renamed Bureau of Marijuana Control).[54][55]

Proposition 64 is not meant in any way to affect, amend, or restrict the statutes provided for medical cannabis in California under Proposition 215.[53]

Resources associated with cultivation

Electricity

It is estimated that in excess of 3% of all power in California is used for the cultivation of cannabis, with each major grower requiring about 5000 kWh every day. One major cause of this high power requirement is the large amount of light required to grow the plants, which is often supplied by lamps as opposed to using the sun as most other crops do. It was reported in March 2018 that Windshark Energy created a small-scale, vertical axis wind turbine with the industry in mind. The turbines would be mounted atop of greenhouses or other growing buildings to help recoup some of the energy used and money spent paying for it.[56]

See also

References

- ↑ "US election: California voters approve marijuana for recreational use". BBC News. 9 November 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ Is California Really Ready For Legal Marijuana?

- 1 2 Robert Clarke; Mark Merlin (1 September 2013). Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany. University of California Press. pp. 181–. ISBN 978-0-520-95457-1.

- ↑ Facts On File, Incorporated (2008). Marijuana. Infobase Publishing. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-1-4381-1824-6.

- ↑ Chris Duvall (15 November 2014). Cannabis. Reaktion Books. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-1-78023-386-4.

- ↑ Martin Booth (16 June 2015). Cannabis: A History. St. Martin's Press. pp. 163–. ISBN 978-1-250-08219-0.

- ↑ (Stats. 1913, Ch. 342, p. 697)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Gieringer, Dale H. (1999). "The Forgotten Origins of Cannabis Prohibition in California" (PDF). Contemporary Drug Problems. 26 (2).

- ↑ (Stats. 1915, Ch. 604, pp. 1067–1068)

- ↑ https://www.scpr.org/programs/offramp/2014/09/19/39399/the-nation-s-first-marijuana-raid-likely-happened/

- ↑ Survey of Drug Addiction in California. California state printing office, H. Hammond, state printer. 1932.

- ↑ Ed Rosenthal (1 July 2009). Marijuana Grower's Handbook: Your Complete Guide for Medical and Personal Marijuana Cultivation. Quick Trading Company. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-0-932551-50-4.

- ↑ Kirse Granat May (2002). Golden State, Golden Youth: The California Image in Popular Culture, 1955-1966. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 189–. ISBN 978-0-8078-5362-7.

- ↑ Emily Brady (18 June 2013). Humboldt: Life on America's Marijuana Frontier. Grand Central Publishing. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-1-4555-0677-4.

- 1 2 Anderson, Patrick (February 27, 1981). High In America: The True Story Behind NORML And The Politics Of Marijuana. The Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670119905.

- ↑ Budman, K B. "IMPACT OF CALIFORNIA'S NEW MARIJUANA LAW (SB 95) REPORT, 1ST". Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ Philip Bean, ed. (2003). Crime: Critical Concepts in Sociology. Routledge. pp. 249–250. ISBN 978-0-415-25267-6. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Marijuana Laws California".

- ↑ "California - NORML". National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML). Archived from the original on January 12, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ Wallace, Bill (November 15, 2000). "Money, Opinion Propelled Prop. 36". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ Bill Text - SB-1449 Marijuana: possession

- ↑ Boire, Richard Glen; Feeney, Kevin (January 26, 2007). Medical Marijuana Law. Ronin Publishing.

- ↑ "Proposition P". marijuanalibrary.org. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Gardner, Fred (August 26, 2014). "The Cannabis Buyers Club: How Medical Marijuana Began in California". marijuana.com. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Heddleston, Thomas R. (June 2012). From the Frontlines to the Bottom Line: Medical Marijuana, the War on Drugs, and the Drug Policy Reform Movement (Thesis). UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Archived from the original on February 16, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Vitiello, Michael (1998). "Proposition 215: De Facto Legalization of Pot and the Shortcomings of Direct Democracy". McGeorge School of Law. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ "Medical Marijuana Initiative Qualifies For November Ballot". NORML. June 6, 1996. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- 1 2 "Proposition 215: Text of Proposed Law" (PDF). ProCon.org.

- ↑ McDonald, Jeff (October 27, 2008). "County pursues medicinal marijuana case". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lee, Martin A. (August 2012). Smoke Signals: A Social History of Marijuana – Medical, Recreational, and Scientific. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-1439102602.

- ↑ Dufton, Emily (December 5, 2017). Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465096169.

- ↑ Sinclair, John (October 27, 2010). "Getting NORML -- A brief history of the movement to legalize marijuana". Detroit Metro Times. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ↑ "Our Mission". California NORML. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ↑ Banks, Sandy (March 29, 2010). "Pot breaks the age barrier". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ↑ Stateman, Alison (March 13, 2009). "Can Marijuana Help Rescue California's Economy?". Time. Time Inc. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ↑ "California Proposition 19, the Marijuana Legalization Initiative (2010)". Ballotpedia. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ Kiel, Matt S. (10 August 2017). "Financing California's Cannabis Businesses: Public Banking Model as a State-Level Solution". The National Law Review. Wilson Elser. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ↑ Black, Lester (19 April 2017). "The Credit Unions and Small Banks That Solved the Cannabis Cash Crisis". The Stranger. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ↑ Angel Jennings and Sarah Parvini (December 31, 2017), "California pot shops prepare for their first day of legal recreational marijuana sales", Los Angeles Times

- ↑ LA Begins Pot Licensing Process, CBS Los Angeles, January 3, 2018

- ↑ "Ca Supreme Court Strikes Down Medical Marijuana Possession, Cultivation Limits". www.canorml.org. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- 1 2 3 Imler, Scott; Gutwillig, Stephen (March 6, 2009). "Medical marijuana in California: a history". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ↑ What's the Cost? -- The Federal War on Patients (PDF), Americans for Safe Access, June 2013, retrieved April 29, 2017

- ↑ Berry, Denis (September 12, 2002). "City leaders stand behind Medical Marijuana at City Hall". Drug Policy Alliance. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ↑ Gardner, Fred (September 2002). "The Raid on WAMM". O'Shaughnessy's. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ↑ Leduff, Charlie; Liptak, Adam (September 18, 2002). "Defiant California City Hands Out Marijuana". The New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ↑ Gaura, Maria Alicia; Stannard, Matthew B. (September 13, 2002). "Santa Cruz officials to defy feds, hand out medical pot at City Hall". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- 1 2 Baily, Eric; Rodriguez, Marcelo (June 5, 2003). "The 'Guru of Ganja' Gets a Day in Jail". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ Eddy, Mark (April 2, 2010), Medical Marijuana: Review and Analysis of Federal and State Policies (PDF), Congressional Research Service

- ↑ Hoeffel, John (October 7, 2011). "Federal crackdown on medical pot sales reflects a shift in policy". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ State-By-State Medical Marijuana Laws, Marijuana Policy Project, December 2016

- 1 2 "Adult Use of Marijuana Act", Retrieved on 12 March 2017.

- ↑ Michael R. Blood and Don Thomson (January 30, 2017), "Building the airplane while it’s being flown": How California looks to build $7B legal pot economy, Associated Press – via The Cannabist

- ↑ PETER HECHT (January 18, 2017), "California's pot czar on upcoming marijuana regulation: "We will not fail"", Sacramento Bee

- ↑ Froese, Michelle. "MITU sees potential for its WindShark vertical-axis turbine to power California's cannabis sector". windpowerengineering.com. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

External links

- California Cannabis Portal, California's official website for information on legal marijuana.

| The Wikibook California Public Policy and Citizen Participation has a page on the topic of: Cannabis policies in California |