Camille Claudel

| Camille Claudel | |

|---|---|

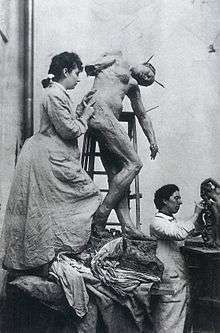

Camille Claudel in 1884 (aged 19) | |

| Born |

8 December 1864 Fère-en-Tardenois, Aisne, France |

| Died |

19 October 1943 (aged 78) Montdevergues, Vaucluse, France |

| Alma mater | Académie Colarossi |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Paul Claudel (brother) |

Camille Claudel (French pronunciation: [kamij klɔdɛl] (![]()

The national Camille Claudel Museum in Nogent-sur-Seine opened in 2017, and the Musée Rodin in Paris has a room dedicated to Claudel's works.

Early years

Camille Claudel was born in Fère-en-Tardenois, Aisne, in northern France, the second child of a family of farmers and gentry. Her father, Louis-Prosper Claudel, dealt in mortgages and bank transactions. Her mother, the former Louise-Athanaïse Cécile Cerveaux, came from a Champagne family of Catholic farmers and priests. The family moved to Villeneuve-sur-Fère while Camille was still a baby. Her younger brother Paul Claudel was born there in 1868. Subsequently, they moved to Bar-le-Duc (1870), Nogent-sur-Seine (1876), and Wassy-sur-Blaise (1879), although they continued to spend summers in Villeneuve-sur-Fère, and the stark landscape of that region made a deep impression on the children.

Camille moved with her mother, brother, and younger sister to the Montparnasse area of Paris in 1881. Her father remained behind, working to support them.

Creative period

Study with Alfred Boucher

Claudel was fascinated with stone and soil as a child, and as a young woman Claudel studied at the Académie Colarossi, one of the few places open to female students.[3] She studied with sculptor Alfred Boucher.[4] (At the time, the École des Beaux-Arts barred women from enrolling to study.)

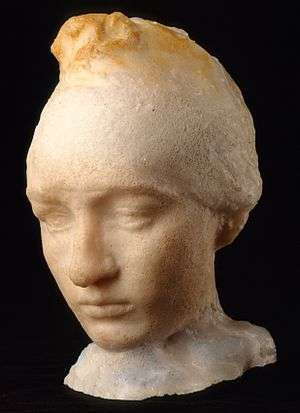

In 1882, Claudel rented a workshop with other young women, mostly English, including Jessie Lipscomb. Alfred Boucher had become her mentor, and also provided inspiration and encouragement to the next generation of sculptors such as Laure Coutan. Claudel was depicted by Boucher in Camille Claudel lisant,[5] and later she sculpted a bust of her mentor.

Before moving to Florence, and after having taught Claudel and other sculptors for over three years, Boucher asked Auguste Rodin to take over the instruction of his pupils. This is how Rodin and Claudel met, and their artistic association and their tumultuous and passionate relationship began.

Auguste Rodin

Around 1884, Claudel started working in Rodin's workshop. She became a source of inspiration for him, and acted as his model, confidante, and lover. She never lived with Rodin, who was reluctant to end his 20-year relationship with Rose Beuret.

Knowledge of the affair agitated her family, especially her mother, who already detested her for not being a male child (who would have replaced her first-born male infant), and never agreed with Claudel's involvement in the arts.[6][7][8] As a consequence, Claudel left the family house. In 1892, after an abortion, Claudel ended the intimate aspect of her relationship with Rodin, although they saw each other regularly until 1898.[9]

Le Cornec and Pollock state that after the sculptors physical relationship ended, because of gender-based censorship and the sexual element of Claudel's work she could not get the funding to get many of her daring ideas realized. Claudel thus had to either depend on Rodin to realize them, or to collaborate with him and let him get the credit as the lionized figure of French sculptures. She also depended on him financially, especially since her loving and wealthy father's death. This allowed her mother and brother, who were suspicious of her lifestyle, to keep the money and let her wander around the streets dressed in beggars' clothes.[10]

Claudel's reputation survived not because of her once notorious association with Rodin, but because of her work. The novelist and art critic Octave Mirbeau described her as "A revolt against nature: a woman genius." Her early work is similar to Rodin's in spirit, but shows an imagination and lyricism quite her own, particularly in the famous Bronze Waltz (1893).

Louis Vauxcelles states that Claudel was the only sculptress on whose forehead shone the sign of genius like Berthe Morisot, the only well-known female painter of the century, and that Claudel's style was more virile than many of her male colleagues. Others like Morhardt and Caranfa concurred, saying that their styles have become so different, with Rodin being more suave and delicate and Claudel being vehement with vigorous contrasts, and this might have been one reason that led to their break up, with her becoming ultimately his rival.[11][12][13]

Claudel's onyx and bronze small-scale La Vague (The Wave) (1897) was a conscious break in style from her Rodin period. It has a decorative quality quite different from the "heroic" feeling of her earlier work.

The Mature Age and other works

After Rodin saw Claudel's The Mature Age for the first time, in 1899, he reacted with shock and anger. He suddenly and completely stopped his support for Claudel. According to Ayral-Clause, Rodin might have put pressure on the ministry of fine arts to cancel the funding for the bronze commission.

The Mature Age (1900) was interpreted by her brother as a powerful allegory of her break with Rodin.

One of Claudel's figures, The Implorer, was produced as an edition of its own, and has been interpreted not as purely autobiographical but as an even more powerful representation of change and purpose in the human condition.[14] Modeled for in 1898 and cast in 1905, Claudel didn't actually cast her own bronze for this work, but instead The Implorer was cast in Paris by Eugene Blot.[15]

In 1902 Claudel completed a large sculpture of Perseus and the Gorgon. The, beginning in 1903, she exhibited her works at the Salon des Artistes français or at the Salon d'Automne.

Shakountala, 1905, is described by Angelo Caranfa as expressing Claudel's desire to reach the sacred, the fruit of her lifelong search of her artistic identity, free from Rodin's constraints. Caranfa suggests that Claudel's impressions of Rodin's deceptions and exploitation of her, as someone who could not become obedient as he wanted her to be and who was expected to conform to society's expectation of what women should be, were not false. Thus Sakountala could be called a clear expression of her solitary existence and her inner search, her journey within.[16]

Ayral-Clause says that despite the fact that Rodin obviously signed a number of her works, this was not specifically treatment of women artists but a treatment of apprentices in general at the time.[17] Others also criticize Rodin for not giving her the acknowledgment or support she deserved.[18][19] Walker argues that most historians believe Rodin did what he could to help her after their separation, and that her destruction of her own oeuvre was partly responsible for the longtime neglect the art world showed her. Walker also says that what truly defeated Camille, who was already recognized as a leading sculptor by many, were the sheer difficulties of the medium and the market: sculpting was an expensive art, and she did not receive many official commissions because her style was highly unusual for the contemporary conservative tastes.[20] Despite this, Le Cornec and Pollock believe she changed the history of arts.

_(8026456955).jpg)

Other authors write that it is still unclear how much Rodin influenced Claudel - and vice versa, how much credit has been taken away from her, or how much he was responsible for her woes. Most modern authors agree that she was an outstanding genius who, starting with wealth, beauty, iron will and a brilliant future even before meeting Rodin, was never rewarded and died in loneliness, poverty, and obscurity.[1][2][21][22][23] Others like Eisen, Matthews, Flemming, and Jansen Estrup suggest it was not Rodin, but her own brother who was jealous with her genius, and that he conspired with her mother, who never forgave her for her supposed immorality, to ruin her and keep her from leaving the hospital.[24][25][26][27][28] Jansen Estrup quotes Paul Claudel as saying, "I am the only genius in this family!" Kavaler-Adler notes that her younger sister Louise, who desired Camille's inheritance and was jealous of her, was delighted at her downfall as well.[29]

Less well known than her love affair with Rodin, the nature of her relationship with Claude Debussy has also been the object of much speculation. Stephen Barr reports that Debussy pursued her: it was unknown whether they ever became lovers.[30] They both admired Degas and Hokusai, and shared an interest in childhood and death themes.[31] When Claudel ended the relationship, Debussy wrote: "I weep for the disappearance of the Dream of this Dream." Debussy admired her as a great artist and kept a copy of The Waltz in his studio until his death. By thirty, Claudel's romantic life had ended.[32][33]

Alleged illness

After 1905 Claudel appeared to be mentally ill. She destroyed many of her statues, disappeared for long periods of time, exhibited signs of paranoia and was diagnosed as having schizophrenia.[34] She accused Rodin of stealing her ideas and of leading a conspiracy to kill her.[35]

After the wedding of her brother in 1906 and his return to China, she lived secluded in her workshop.[34][35]

Confinement

Her father, who approved of her career choice, tried to help her and supported her financially. When he died on 2 March 1913, Claudel was not informed of his death. On 10 March 1913 at the initiative of her brother, she was admitted to the psychiatric hospital of Ville-Évrard in Neuilly-sur-Marne. The form read that she had been "voluntarily" committed, although her admission was signed by a doctor and her brother. There are records to show that, while she did have mental outbursts, she was clear-headed while working on her art.

Doctors tried to convince the family that she need not be in the institution, but still they kept her there.[36]

In 1914, to be safe from advancing German troops, the patients at Ville-Évrard were at first relocated to Enghien. On 7 September 1914 Camille was transferred with a number of other women, to the Montdevergues Asylum, at Montfavet, six kilometres from Avignon. Her certificate of admittance to Montdevergues was signed on 22 September 1914; it reported that she suffered "from a systematic persecution delirium mostly based upon false interpretations and imagination".[37]

For a while, the press accused her family of committing a sculptor of genius. Her mother forbade her to receive mail from anyone other than her brother. The hospital staff regularly proposed to her family that Claudel be released, but her mother adamantly refused each time.[36] On 1 June 1920, physician Dr. Brunet sent a letter advising her mother to try to reintegrate her daughter into the family environment. Nothing came of this.

Paul Claudel visited his confined sister seven times in 30 years, in 1913, 1920, 1925, 1927, 1933, 1936, and 1943. He always referred to her in the past tense. Their sister Louise visited her just one time, in 1929. Her mother, who died in June, 1929, never visited Camille.[38]

In 1929 sculptor and Claudel's former friend Jessie Lipscomb visited her, and afterwards insisted "it was not true" that Claudel was insane. Rodin's friend, Mathias Morhardt, insisted that Paul was a "simpleton" who had "shut away" his sister of genius.[39]

Camille Claudel died on 19 October 1943, after having lived 30 years in the asylum at Montfavet (known then as the Asile de Montdevergues, now the modern psychiatric hospital Centre hospitalier de Montfavet). Her brother Paul had been informed of his sister's terminal illness in September and, with some difficulty, had crossed Occupied France to see her, but was not present at either her death or funeral.[40] Her sister did not make the journey to Montfavet.

Claudel was interred in the cemetery of Montfavet, and eventually her remains were buried in a communal grave at the asylum.[36][37] From the 2002 book, Camille Claudel, A Life: "Ten years after her death, Camille's bones had been transferred to a communal grave, where they were mixed with the bones of the most destitute. Joined forever to the ground she tried to escape for so long, Camille never, ever, returned to her beloved Villeneuve. Paul's neglect regarding his sister's grave is hard to forgive...while Paul decided not to be burdened with his sister's grave, he took great pains, on the contrary, in choosing his own final resting place, naming the exact location – in Brangues, under a tree, next to his grandchild – and citing the precise words to be written on the stone. Today his admirers pay homage to his memory at his noble grave; but of Camille there is not a trace. In Villeneuve, a simple plaque reminds the curious visitor that Camille Claudel once lived there, but her remains are still in exile, somewhere, just a few steps away from the place where she was sequestered for thirty years."[41]

French National Museum

In March 2017 France opened a national museum dedicated to Claudel's work in her teenage home town of Nogent-sur-Seine. The Musée Camille Claudel[42] displays approximately half of Claudel's 90 surviving works.[43][44]

Plans were announced in 2003 to turn the Claudel family home at Nogent-sur-Seine into a museum, and it was negotiating to buy works from the Claudel family. These include 70 pieces by Camille Claudel, including a bust which she sculpted of Rodin.[45]

Legacy

Though she destroyed much of her work, about 90 statues, sketches and drawings survive.

Some authors argue that Henrik Ibsen based his last play, 1899's When We Dead Awaken, on Rodin's relationship with Claudel.[46][47][48][49]

In 1951, Paul Claudel organized an exhibition at the Musée Rodin, which continues to display her sculptures. A large exhibition of her works was organized in 1984. In 2005 a large art display featuring the works of Rodin and Claudel was exhibited in Quebec City (Canada), and Detroit, Michigan, in the US. In 2008, the Musée Rodin organized a retrospective exhibition including more than 80 of her works.

The publication of several biographies in the 1980s sparked a resurgence of interest in her work.

Camille Claudel (1988) was a dramatization of her life based largely on historical records. Directed by Bruno Nuytten, co-produced by Isabelle Adjani, starring herself as Claudel and Gérard Depardieu as Rodin, the film was nominated for two Academy Awards in 1989. Another film, Camille Claudel 1915, directed by Bruno Dumont and starring Juliette Binoche as Claudel, premiered at the 63rd Berlin International Film Festival in 2013. The 2017 film, Rodin, co-stars Izïa Higelin as Claudel.

Composer Jeremy Beck's Death of a Little Girl with Doves (1998), an operatic soliloquy for soprano and orchestra, is based on the life and letters of Camille Claudel. This composition has been recorded by Rayanne Dupuis, soprano, with the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra.[50] Beck's composition has been described as "a deeply attractive and touching piece of writing ... [demonstrating] imperious melodic confidence, fluent emotional command and yielding tenderness." [51]

Seattle playwright S.P. Miskowski's La Valse (2000) is a well-researched look at Claudel's life.[52][53]

Composer Frank Wildhorn and lyricist Nan Knighton's musical Camille Claudel was produced by Goodspeed Musicals at The Norma Terris Theatre in Chester, Connecticut in 2003.[54]

In 2005, Sotheby's sold a second edition La Valse (1905, Blot, number 21) for $932,500.[55] In a 2009 Paris auction, Claudel's Le Dieu Envolé (1894/1998, Valsuani, signed and numbered 6/8) has a high estimate of $180,000,[56] while a comparable Rodin sculpture, L'eternelle Idole (1889/1930, Rudier, signed) has a high estimate of $75,000.[57]

In 2011 world premiere of Boris Eifman's new ballet Rodin took place in Saint-Petersburg, Russia. The ballet is dedicated to the life and creative work sculptor Auguste Rodin and his apprentice, lover and muse, Camille Claudel.[58]

In 2012, the world premiere of the play Camille Claudel took place. Written, performed and directed by Gaël Le Cornec, premiered at the Pleasance Courtyard Edinburgh Festival, the play looks at the relationship of master and muse under the perspective of Camille at different stages of her life.[59]

See also

- Category:Sculptures by Camille Claudel

- Camille Claudel – 1988 biographical fictional film with Isabelle Adjani (Camille) and Gérard Depardieu (Rodin), France, nominated for two Academy Awards

- Camille Claudel, 2003 musical

- Camille Claudel 1915 - 2013 French biopic written and directed by Bruno Dumont, starring Juliette Binoche as Camille Claudel.

- Rodin - 2017 film, with Izïa Higelin portraying Claudel.

References

- 1 2 Flemming, Laraine E. (Jan 1, 2016). Reading for Results. Cengage Learning, Jan 1, 2016. p. 721. ISBN 9781305500525.

- 1 2 Montagu, Ashley (1999). The Natural Superiority of Women. Rowman Altamira. p. 217. ISBN 9780761989820.

- ↑ Heller, Nancy (2000). Women Artists: Works from the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Rizzoli Intntl. p. 64. ISBN 0-8478-2290-7.

...one of the few art academies in France open to female students.

- ↑ Christiane., Weidemann, (2008). 50 women artists you should know. Larass, Petra., Klier, Melanie, 1970-. Munich: Prestel. ISBN 9783791339566. OCLC 195744889.

- ↑ Camille Claudel révélée, exporevue, magazine, art vivant et actualité at www.exporevue.com

- ↑ Runco, Mark A.; Pritzker, Steven R. (May 20, 2011). Encyclopedia of Creativity. Academic Press. p. 763. ISBN 9780123750389.

- ↑ Mahon, Elizabeth Kerri (2011). Memories of Our Lost Hands: Searching for Feminine Spirituality And Creativity. Penguin. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9781101478813.

- ↑ Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth, J. Adolf (1994). Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel. Prestel. p. 109. ISBN 9783791313825.

- ↑ Mahon, Elizabeth K. Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women. New York: Penguin Group, 2011. Print.

- ↑ Akbar, Arifa (2012). "How Rodin's tragic lover shaped the history of sculpture". https://www.independent.co.uk.

- ↑ Eisen 2003, p. 308.

- ↑ Vollmer 2007, p. 249.

- ↑ Rodin, Auguste; Crone, Rainer; Salzmann, Siegfried (1997). Rodin: Eros and creativity. Prestel. p. 41. ISBN 9783791318097.

- ↑ The different scales, the different modes of plasticity, and gender-representation, of the three figures which make up this important group, enable a more universal thematic and metaphoric stylistics related to the ages of existence, childhood, maturity, and the perspective of the transcendent (v. Angela Ryan, "Camille Claudel: the Artist as Heroinic Rhetorician." Irish Women's Studies Review vol 8: Making a Difference: Women and the Creative Arts. (December 2002): 13-28).

- ↑ "Met Museum".

- ↑ Caranfa, Angelo (1999). CamilleClaudel: A Sculpture of Interior Solitude. Associated University Presse. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9780838753910.

- ↑ Vollmer, U. (Sep 3, 2007). Seeing Film and Reading Feminist Theology: A Dialogue. Springer. pp. 75–76. ISBN 9780230606852.

- ↑ Axelrod, Mark (2004). Borges' Travel, Hemingway's Garage: Secret Histories. University of Alabama Press. p. 129. ISBN 9781573661140.

- ↑ Maisel, Eric; Gregory, Danny; Hellmuth, Claudine (Oct 5, 2005). A Writer's Paris. Writer's Digest Books. p. 81. ISBN 9781582973593.

- ↑ Walker, John Albert (2010). Art and Artists on Screen. John Albert Walker. p. 124. ISBN 9780954570255.

- ↑ A. Runco, Mark; R. Pritzker, Steven (2011). Encyclopedia of Creativity. Academic Press. ISBN 9780123750389.

- ↑ Zohrevandi, Elaheh; Allahyari,, Effat; Jayakumar, Kirthi; Tarazona, Katherine Vasquez; Kumar, Aanchal; Reed, Elsie; Mohseni, Fatemeh; Barazandeh, Hadi; Aguas, Lylin; Hewitt, Willow; Brigneti, Paola. DeltaWomen January 2012 Issue - Women Against The World. Lulu.com. p. 4. ISBN 9781471055973.

- ↑ Chilvers, Ian; Glaves-Smith, John (2009). A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780199239658.

- ↑ Elsen, Albert E.; Haas, Walter A. (Mar 13, 2003). Rodin's Art : The Rodin Collection of Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center of Visual Arts at Stanford University: The Rodin Collection of Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center of Visual Arts at Stanford University. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 306. ISBN 9780198030614.

- ↑ Stories, Wander (2016). Paris Tour Guide Top 5: Travel guide and tour as with the best local guide. WanderStories. ISBN 9789949577132.

- ↑ Flemming 2016, p. 721.

- ↑ Jansen Estrup, H. F. (2007). War Stories for My Grandchildren: A Memoir in Short Stories. iUniverse. ISBN 9780595430987.

- ↑ Mathews, Patricia Townley (1999). Passionate Discontent: Creativity, Gender, and French Symbolist Art. University of Chicago Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 9780226510187.

- ↑ Kavaler-Adler, Susan (2013). The Creative Mystique: From Red Shoes Frenzy to Love and Creativity. Routledge. ISBN 9781317795681.

- ↑ Barr, Stephen Anthony; West Virginia University (2007). "Pleasure is the Law": Pelleas Et Melisande as Debussy's Decisive Shift Away from Wagnerism - DMA Research Project. ProQuest. p. 106. ISBN 9780549439837.

- ↑ Lockspeiser, Edward (1978). Debussy: Volume 1, 1862-1902: His Life and Mind. CUP Archive. p. 183. ISBN 9780521293419.

- ↑ Seroff, Victor I. (1970). Debussy; musician of France. Books for Libraries Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780836980325.

- ↑ Schierse Leonard, Linda (1994). Meeting the Madwoman: An Inner Challenge for Feminine Spirit. Bantam Books. p. 124. ISBN 9780553373189.

- 1 2 "Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria - Camille Claudel: a revulsion of nature. The art of madness or the madness of art?". Scielo.br. 6 January 1990. doi:10.1590/S0047-20852006000300012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- 1 2 Butler, Ruth (1996). Rodin: The Shape of Genius. Yale University Press. p. 282. ISBN 0300064985.

- 1 2 3 Kerri Mahon, Elizabeth (2011). Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women. New York: Penguin Group. p. 279. ISBN 9780399536458.

- 1 2 Ayral-Clause, Odile (2002). Camille Claudel: a life. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris Corp. p. 210. ISBN 9780810940772.

- ↑ Ayral-Clause, Odile, p. 217, 222, 225, 242, 245, 250, 235

- ↑ Boucher Tehan, Arline (2010). "3". The Gates of Hell: Rodin's Passion in Stone. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris Corp. ISBN 9781453548288.

Rodin’s old friend and Camille's supporter, Matias Morhardt, was aghast at her plight and declared: “Paul Claudel is a simpleton. When one has a sister who is a genius, one doesn’t abandon her. But he always thought he was the one who had genius.”

- ↑ Ayral-Clause, Odile, p. 251

- ↑ Ayral-Clause, Odile. Camille Claudel: A Life. New York: Abrams, 2002, p. 253

- ↑ "Musée Camille Claudel -". www.museecamilleclaudel.fr.

- ↑ Alberge, Dalya (2017-02-25). "Overshadowed by Rodin, but his lover wins acclaim at last". The Guardian. London. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ↑ C., Maïlys (29 December 2016). "Musée Camille Claudel : ouverture en mars 2017 à Nogent-sur-Seine". Sortira Paris. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ↑ Webster, Paul (2003-03-23). "Fame at last for Rodin's lost muse". The Guardian. London. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ↑ Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth, J. Adolf (1994). Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel. Prestel. ISBN 978-3-7913-1382-5.

- ↑ Bremel, Albert (1996). Contradictory characters: an interpretation of the modern theatre. Northwestern University Press. pp. 282–283. ISBN 978-0-8101-1441-8.

- ↑ Binding, Paul (2006). With vine-leaves in his hair: the role of the artist in Ibsen's plays. Norvik Press. ISBN 978-1-870041-67-6.

- ↑ Templeton, Joan (2001). Ibsen's women. Cambridge University Press. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-521-00136-6.

- ↑ "Innova Recordings: Jeremy Beck - Wave". Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ "Jeremy Beck - Wave". MusicWeb International.com. December 2004. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Wiecking, Steve. "The Expanding Universe". The Stranger. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- ↑ Berson, Misha (2000-02-10). "Entertainment & the Arts | Solid acting helps keep `La Valse' in step | Seattle Times Newspaper". community.seattletimes.nwsource.com. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- ↑ "Wildhorn and Knighton's Camille Claudel, the Musical, Ends September 7 at Goodspeed". Playbill.com. 7 September 2003. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ↑ http://www.sothebys.com/app/live/lot/LotDetail.jsp?lot_id%3D159563476. Retrieved 29 November 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://www.sothebys.com/app/live/lot/LotDetail.jsp?lot_id%3D159557282. Retrieved 29 November 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://www.sothebys.com/app/live/lot/LotDetail.jsp?lot_id%3D159567009. Retrieved 29 November 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Rodin". www.eifmanballet.ru. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

- ↑ Akbar, Arifa. "Interview with Gael Le Cornec and Dr Pollock" The Independent, London, 11 August 2012. retrieved 23 December 2013.

References

- Ayral-Clause, Odile. Camille Claudel: A Life. New York: Abrams, 2002.

- Lenormand-Romain, Antoinette et al. Camille Claudel and Rodin: Fateful Encounter. New York: Gingko Press, 2005.

- Rivière, Anne & Bruno Gaudichon. Camille Claudel: Catalogue raisonné. Paris: Adam Biro, 2001.

Further reading

- Miller, Joan Vita (1986). Rodin: the B. Gerald Cantor Collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-443-2. (which contains material on Claudel)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Camille Claudel |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Camille Claudel. |

- "Musée Camille Claudel".

- Review of 2008 Claudel exhibition at Musee Rodin, Paris

- Camille Claudel and Rodin: Fateful Encounter at Detroit Institute of Arts 2005

- Claudel pages, including biography and timeline, at rodin-web.org

- Camille Claudel at artcyclopedia.com

- Camille Claudel: a Life of Struggle

- Camille Claudel, Of Dreams and Nightmares

- Camille Claudel: a Life of Struggle

- An Eye on Art: L'Age Mûr

- Ron Schuler's Parlour Tricks: Camille Claudel

- CBC interview for the 2005 exhibition in Quebec

- Rodin Ballet by Boris Eifman

- Claudel's The Age of Maturity, Ben Pollitt at Smarthistory

- (in Catalan) «La dona artista i el poder : homenatge a Camille Claudel» (audio). l'Arxiu de la Paraula. Ateneu Barcelonès, 2014.

- Camille Claudel in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website