Brownhill Inn

Brownhill Inn, now just called Brownhill (NX 902 911), is an inn approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) mile south of Closeburn, on the A76, which itself is about 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Thornhill, in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. Built in approximately 1780, this old coaching inn has undergone extensive changes, and only the south side of the original property remains. The inns facilities used to include the once-extensive livery stables on the west side of the road, but these have been sold and converted to farm buildings. The inn was the first changing place for horses hauling coaches from Dumfries.[1]

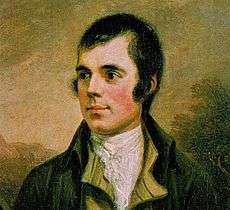

Robert Burns

Robert Burns was purported to have spent many an evening at the inn, which lies about 7 miles north of his once time home, Ellisland Farm. The landlord at the time, Mr John Bacon, took a keen interest in the poet and even bought the bed from Gilbert Burns at nearby Dinning Farm in 1798 that Burns was born in and installed it at Brownhill, charging people to see it. His groom, Joe Langhorne, slept in it for many years and in 1829 purchased it himself.[2] He took it to Dumfries where the bed was eventually broken up by a relative and used to make snuff boxes that bore a commemorative inscription.[3][4]

The Ayrshire Monthly Newsletter of 1844 reported that "At the sale of the effects of Mr Bacon, Brownhill Inn, after his death in 1825, his snuff-box, being found to bear the inscription: Robert Burns - Officer of the Excise - although only a horn mounted with silver, brought £5. It was understood to have been presented by Burns to John Bacon, with whom he had spent many a merry night."[5]

When asked on one occasion by a commercial traveller named Ladyman to prove that it was really him that he was dining on bacon and beans with, Burns made up on the spot the following verse that highlighted the habit of the landlord to sometimes overstay his welcome:[6]

|

"At Brownhill we always get dainty good cheer, |

It is also reported that one summer evening whilst at the inn with Dr Purdie of Sanquhar and another friend,[7] Burns met a soldier and upon listening to his story of the adventures he had lived through was inspired to write his famous song "The Soldier's Return"[8]

Alexander Pope's 'Song by a Person of Quality' was read out to Burns at Brownhill by a friend who went on to suggest that it was of a standard that was beyond his abilities, stating that 'The muse of Kyle cannot match the muse of London City'. Burns took the paper and after a moments thought composed and recited 'Delia - An Ode' that was published in the London Star of 1789.[9]

He was inspired by the visit of a weary soldier to Brownhill Inn in 1793 to write "The Soldier's Return", quite possibly at the inn itself.[10]

His other recorded pursuits at the inn included annoying the landlord's wife by engraving a glass tumbler that became part of Sir Walter Scott's collections[11] and also engraving window panes with his diamond point pen (the lines on the panes were so crude or inappropriate that they were carefully removed by then laird of Closeburn upon the poet's death, but later destroyed by his son to save the poet's reputation).[12][13]

It is also recorded that 'One Monday even' he sent a rhymed epistle to William Stewart, beginning :

|

"In honest Bacon's ingle-neuk, |

William Stewart was the father of "lovely Polly Stewart", and the brother-in-law to Mr Bacon the Landlord.

In 1788 Catherine Stewart (Mrs Bacon) inspired Burns to compose the poem "The Henpecked Husband" upon refusing to serve her husband and the poet with more liquor when they were engaged in a drinking bout at Brownhill.[15]

|

"Curs'd be the man, the poorest wretch in life, |

Other famous faces

As well as Robert Burns, other famous poets also stayed at the inn. It is noted in Dorothy Wordsworth's diary, that she, her brother William and Samuel Coleridge also stayed here during their tour of Scotland. However it seems that she was not quite as taken with the inn as Burns, writing "It was as pretty a room as a thoroughly dirty one could be a square parlour painted green, but so covered over with smoke and dirt that it looked not unlike green seen through black gauze." She also commented on the lack of tree although she was impressed by the quantity of corn in the fields.[16]

The Free Church

The Rev. Patrick Barrowman of Glencairn was first 'Free Church' minister in the area following 'The Great Disruption' of 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers of the Church broke away in a dispute over the issue of the Church's relationship with the State. The congregation at first had no place of worship however over the winter of 1843-4 the landlord of Brownhill Inn allowed them to use a large stable of twelve stalls and after cleaning and whitewashing it formed a most acceptable temporary church. In the summer months the they made use of the stack yard and even carried out baptisms there. Sir James Menteth stepped forward with an offer of land and the congregation had built their own church by the end of 1844.[17]

Recent history

In more recent times, the property has served as a farm, including cheesemaking and, according to local lore, a courthouse and hotel. It is now a private family home and photography studio.

Micro-history

On 2 November 1860 Mary Kellock, wife of Robert Wightman, died at Brownhill aged 77 years and was buried in Dalgarnock.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ Watson, R. (1901). Closeburn (Dumfriesshire). Reminiscent, Historic & Traditional. Inglis Ker & Co. p. 132.

- ↑ Wood, Rog (2011). Upper Nithsdale Folklore. Creedon. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-907931-03-1.

- ↑ Mackay, James (1988). Burns Lore of Dumfries and Galloway. Alloway. p. 16. ISBN 0-907526-36-5.

- ↑ Wood, Rog (2011). Upper Nithsdale Folklore. Creedon. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-907931-03-1.

- ↑ Purdie, David (2013). Maurice Lindsay's The Burns Encyclopaedia. Robert Hale. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7090-9194-3.

- ↑ Douglas, William (1938). The Kilmarnock Edition of the Poetical Works of Robert Burns. The Scottish Daily Express. p. 339.

- ↑ Mackay, James (1988). Burns Lore of Dumfries and Galloway. Alloway. p. 16. ISBN 0-907526-36-5.

- ↑ "Brownhill/ Closeburn Thornhill Dumfriesshire | McEwan Fraser Legal". Mcewan Fraser Legal Solicitors and Estate Agents. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ Mackay, James (1988). Burns Lore of Dumfries and Galloway. Alloway. p. 16. ISBN 0-907526-36-5.

- ↑ Watson, R. (1901). Closeburn (Dumfriesshire). Reminiscent, Historic & Traditional. Inglis Ker & Co. p. 132.

- ↑ Watson, R. (1901). Closeburn (Dumfriesshire). Reminiscent, Historic & Traditional. Inglis Ker & Co. p. 137.

- ↑ Douglas, William (1938). The Kilmarnock Edition of the Poetical Works of Robert Burns. The Scottish Daily Express. p. 340.

- ↑ Watson, R. (1901). Closeburn (Dumfriesshire). Reminiscent, Historic & Traditional. Inglis Ker & Co. p. 135.

- ↑ "Robert Burns Country: The Burns Encyclopedia: Stewart, William (1749? - 1812)". www.robertburns.org. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ Mackay, James (1988). Burns Lore of Dumfries and Galloway. Alloway. p. 16. ISBN 0-907526-36-5.

- ↑ "Full text of "Journals Of Dorothy Wordsworth Vol I"". www.archive.org. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ Watson, R. (1901). Closeburn (Dumfriesshire). Reminiscent, Historic & Traditional. Inglis Ker & Co. p. 82.

- ↑ Wright, Margaret (2005). Dalgarnock Kirkyard Memorial Inscriptions. Dumfries and Galloway Family Research Centre. p. 16.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brownhill Inn. |