Highland Branch

| Highland Branch | |

|---|---|

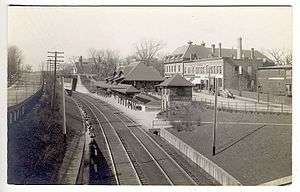

Newton Centre station after the 1905–1907 grade crossing project lowered the right-of-way | |

| Overview | |

| System | Boston and Albany Railroad |

| Status | Closed |

| Locale | Boston, Massachusetts |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 1886 |

| Closed | 1958 |

| Character | Grade-separated double track |

The Highland Branch, also known as the Newton Highlands Branch, was a suburban railway line in Boston, Massachusetts. It was opened by the Boston and Albany Railroad in 1886 to serve the growing community of Newton, Massachusetts. The line was closed in 1958 and sold to the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA), which reopened it in 1959 as a light rail line, now known as the D Branch of the Green Line.

The first section of what became the Highland Branch was built by the Boston and Worcester Railroad between Boston and Brookline in 1847. The Charles River Branch Railroad, a forerunner of the New York and New England Railroad, extended the line to Newton Upper Falls in 1852. The B&A bought the line in 1883 and extended to Riverside, rejoining its main line there. The MTA electrified the line when it rebuilt it for light rail use.

The conversion of the Highland Branch into a light rail line was pioneering in several ways. Amid a backdrop of failing private passenger service in the United States, it was the first time a government entity in that country had assumed full responsibility for losses on a route. It was also the only example of converting an extant commuter rail line to light rail use.

History

Highland Branch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Precursors

What became the Highland Branch was built in stages. The initial segment was the Boston and Worcester Railroad's Brookline Branch, which opened in 1847. This line stretched 1.55 miles (2.49 km) from a junction with the Boston and Worcester main line south of Kenmore Square southwest to the current location of the Brookline Village station in Brookline.[1] The Charles River Branch Railroad built west 6.1 miles (9.8 km) from Brookline to Newton Upper Falls. This extension opened in November 1852.[2]

By the early 1870s the Boston and Worcester had become the Boston and Albany Railroad (B&A), itself destined to become part of the New York Central Railroad system. The tracks beyond Brookline, which now reached Woonsocket, Rhode Island, belonged to the New York and New England Railroad, a forerunner of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad. New York and New England trains used the B&A's route via Brookline to reach Boston.[3]

Suburban service

The citizens of Newton were dissatisfied with their service to Boston and since the early 1870s and had pressured both the Boston and Albany and the New York and New England to improve service, without result. Among these proposals was for the NY&NE to sell part of its Woonsocket line to the B&A, which would then build west through Newton Highlands to Riverside, on its main line from Boston to Albany, New York. This would create a loop or "circuit" between Boston and Riverside. The founding of the Newton Circuit Railroad by a group of Newton citizens in 1882, with the stated goal of completing the circuit by building a 7-mile (11 km) line from Brookline to Riverside, prompted the two railroads to take action.[4]

In 1883 the New York and New England sold the line between Brookline and Newton Highlands to the B&A for $411,400.[5] The B&A completed the missing 3 miles (4.8 km) and opened the new branch on May 16, 1886.[6] To encourage commuter traffic the B&A offered reduced-fare commutation tickets.[7] The introduction of frequent service to Boston led a population boom in Newton.[8]

Between 1905–1907 the Boston and Albany undertook a project to remove grade crossings along the branch. The line's elevation was lowered by as much as 10.5-foot (3.2 m) in some places in order to permit road traffic to cross overhead. Two stations, Newton Highlands and Newton Centre, were remodeled to accommodate the lower platforms. At this time service over the line was almost exclusively passenger, with just one scheduled freight train per day.[9]

Trains which traveled from Boston to Riverside via the Highland Branch returned via the main line, thus completing the "circuit". In 1904 a round trip took 1 hour and 15 minutes.[10] The B&A main line was quadruple-tracked between Boston and Riverside; tracks 3 and 4 were used by suburban trains. The B&A upgraded Brookline Junction to centralized traffic control (CTC) in 1932, improving the flow of traffic between the branch and the main line.[11]

Sale to MTA

The Massachusetts state legislature had first proposed replacing the conventional train service on the Highland Branch with streetcars running from the subway in 1926.[12] The idea returned in the mid-1950s as a combination of factors, both general and specific, made the concept attractive. The commuter rail business had ceased to be profitable for most railroads in the United States. Causes included high structural costs of doing business, loss of demand outside of rush hour, and restrictive regulations.[13] The Boston-area railroads were not immune to these trends, and as the decade wore on sought to end or reduce their money-losing commuter operations.[14] In addition, the extension of the Massachusetts Turnpike over part of the B&A main line would reduce its capacity going forward.[12]

The Metropolitan Transit Authority first proposed buying the Highland Branch and rebuilding it as a light rail line in 1956, for a total estimated cost of $9 million.[15] The state legislature approved a total of $9.2 million.[12] The MTA bought the Highland Branch from the Boston and Albany in 1958 for $600,000.[16] Daily patronage on the branch had fallen to 2,200 passengers.[17] Even as the MTA took this action, the Boston and Maine Railroad was reducing service on its lines radiating out of North Station and the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad threatened to end all service on the Old Colony Railroad lines.[14]

The MTA reopened the branch as a light rail line, now called the Green Line "D" Branch, on July 4, 1959. Rehabilitating the branch, including installing overhead electrification (a step the B&A considered but never undertook), came to $8 million. Daily ridership was 25,000, ten times what the B&A trains had carried at the end.[17][18] The project was "ahead of schedule and under budget", and ridership exceeded projections. The faster acceleration of the electric streetcars permitted faster operation between downtown and Riverside (35 minutes versus 40 minutes) than the conventional trains they replaced.[19] While other government entities were subsidizing passenger operations around the United States, it was the only example at that time of a government entity taking on the entire cost of what had been a private operation,[20] and the only case of a commuter rail line converted to light rail.[21]

Stations

The creation of the circuit service over the Highland Branch coincided with a "major program of capital investment and improvements" by the Boston and Albany.[22] The B&A commissioned Henry Hobson Richardson to design the three stations opening on the new section through Newton Highlands: Eliot, Waban, and Woodland. Richardson also designed a new building for Chestnut Hill, which was located on the section purchased from the New York and New England.[7] The other station buildings on the former NY&NE were replaced by new buildings designed by the firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge. These included Newton Highlands, Reservoir, Newton Centre, Brookline Hills, Riverside, and Longwood.[23] Ignored in this renewal program was Brookline, dismissed by Charles Mulford Robinson in 1902 as "disappointing...a brick structure of an earlier date."[24]

Notes

- ↑ Poor 1860, pp. 104–105

- ↑ Poor 1860, p. 89

- ↑ "The Newton Circuit Railroad". American Railroad Journal: 415. June 17, 1882.

- ↑ Ochsner 1988, p. 111

- ↑ "Annual Reports: Boston & Albany". St. Louis Railway Register. Vol. 9 no. 10. March 8, 1884. p. 117.

- ↑ Ochsner 1988, pp. 111–112

- 1 2 Ochsner 1988, p. 114

- ↑ Fleishman 1999, p. 27

- ↑ Whitney, Walter C. (November 30, 1907). "Grade Crossing Abolition at Newton Highlands and Newton Centre, Mass". The Engineering Record. 56 (22): 586–589.

- ↑ Official Guide of the Railways. New York: National Railway Publication Co. January 1904. p. 236. OCLC 6340864.

- ↑ "Remote Control with C.T.C. Equipment on Boston & Albany". Railway Signaling. 25 (10): 293. October 1932.

- 1 2 3 Allen 1999, p. 42

- ↑ Hilton 1962, pp. 173–175

- 1 2 Hurley, Cornelius F. (May 26, 1958). "State Must Act This Week To Keep Old Colony Running". North Adams Transcript. p. 7. Retrieved June 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "MTA Has Plan To Extend Lines On B&A Roadbed". The Berkshire Eagle. September 6, 1956. p. 9. Retrieved June 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Hilton 1962, p. 177

- 1 2 "Boston Rides Old Rail Line On 20c Fare". The Pittsburgh Press. November 15, 1959. p. 43. Retrieved June 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Cheney & Sammarco 1999, p. 129

- ↑ Allen 1999, p. 43

- ↑ Hilton 1962, p. 181

- ↑ Allen 1999, p. 40

- ↑ Ochsner 1988, p. 109

- ↑ Ochsner 1988, pp. 127–131

- ↑ Robinson 1902, p. 568

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Highland Branch. |

- Allen, John (1999). "Inner Zone Commuter Rail as an Opportunity for Light Rail: Lessons from Boston's Riverside Line". Transportation Research Record. 1677 (1): 40–47. doi:10.3141/1677-05. ISSN 0361-1981.

- Cheney, Frank; Sammarco, Anthony M. (1999). Boston in Motion. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-0087-4.

- Fleishman, Thelma (1999). Newton. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3774-0.

- Hilton, George W. (Summer 1962). "The Decline of Railroad Commutation". Business History Review. 36 (2). doi:10.2307/3111454. ISSN 0007-6805.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (June 1988). "Architecture for the Boston & Albany Railroad: 1881–1894". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 47 (2): 109–131. doi:10.2307/990324. ISSN 0037-9808.

- Poor, Henry Varnum (1860). History of the Railroads and Canals of the United States. 1. OCLC 950951354.

- Robinson, Charles Mulford (November 1902). "A Railroad Beautiful". House & Garden. Vol. 2 no. 11. pp. 564–570.