British entry into World War I

Great Britain entered World War I on 4 August 1914 when the king declared war after the expiration of an ultimatum.

Background

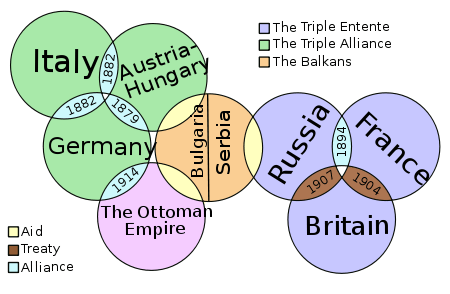

For much of the 19th century, Britain pursued a policy later known as splendid isolation, which sought to maintain the balance of power in Europe without formal alliances. As Europe divided into two power blocs during the 1890s, the 1895-1905 Conservative government realised this left Britain dangerously exposed.[1] This resulted in the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance, followed by King Edward VII's 1903 visit to Paris. By reducing anti-British feeling in France, it led to the 1904 Entente Cordiale, the first tangible impact being British support for France against Germany in the 1905 Moroccan Crisis.

In 1907, the new Liberal government agreed the Anglo-Russian Convention. Like the Entente, the Convention focused on resolving colonial disputes but by doing so, paved the way for wider co-operation and allowed Britain to refocus its naval resources in response to German naval expansion.[2]

The 1911 Agadir Crisis encouraged secret military negotiations between France and Britain in the case of war with Germany. A British Expeditionary Force of 100,000 men would be landed in France within two weeks of war, while naval arrangements allocated responsibility for the Mediterranean to France, with the Royal Navy looking after the North Sea and the Channel, including Northern France.[3] Britain was effectively bound to support France in a war against Germany regardless but this was not widely understood outside government or the military.

Decision for war

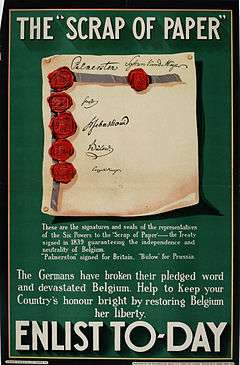

After British leaders increasingly had a sense of commitment to defending France against Germany – first if Germany again conquered France, it would become a major threat to British economic, political and cultural interests. Secondly, partisanship was involved. The Liberal Party was identified with internationalism and free trade, and opposition to jingoism and warfare. By contrast the Conservative Party was identified as the party of nationalism and patriotism; Britons expected it "to show capacity in running a war." [4] Liberal voters demanded peace, but they also were outraged when the Germans treated Belgian neutrality as a worthless "scrap of paper" (in the words of the German chancellor ridiculing the Treaty of London (1839)). Germany invaded Belgium en route to a massive attack on France early on the morning of 4 August. The victims called upon Britain for military rescue under the 1839 treaty and in response, London gave Berlin an ultimatum, which was ignored. The king declared war on Germany that same evening August 4, 1914.[5]

As late as August 1, 1914, the great majority of Liberal—both voters and cabinet members—strongly opposed going to war.[6] The German invasion of Belgium was such an outrageous violation of international rights that Liberals agreed for war on August 4. Historian Zara Steiner says:

- The public mood did change. Belgium proved to be a catalyst which unleashed the many emotions, rationalizations, and glorifications of war which had long been part of the British climate of opinion. Having a moral cause, all the latent anti-German feelings, that by years of naval rivalry and assumed enmity, rose to the surface. The 'scrap of paper' proved decisive both in maintaining the unity of the government and then in providing a focal point for public feeling.[7]

The Liberals succeeded in mending their deep division over warfare. Unless the Liberal government acted decisively against the German invasion of France, its top leaders including Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, Foreign Minister Edward Grey, navy minister Winston Churchill and others would resign, leading to control of the British government by the much more pro-war Conservative Party. Mistreatment of Belgium itself was not a main cause British entry, but it was a main justification used extensively in wartime propaganda to motivate the British people.[8]

The German high command was aware that entering Belgium would trigger British intervention but decided the risk was acceptable; they expected it to be a short war while their ambassador in London claimed civil war in Ireland would prevent Britain from assisting France.[9]

Historians looking at the July crisis typically conclude that Grey:

- was not a great foreign secretary but an honest, reticent, punctilious English gentleman.... He exhibited a judicious understanding of European affairs, a firm control of his staff, and a suppleness and tact in diplomacy, but he had no boldness, no imagination, no ability to command men and events. [Regarding the war]He pursued a cautious, moderate policy, one that not only fitted his temperament, but also reflected the deep split in the Cabinet, in the Liberal party, and in public opinion.[10]

Irish crisis on hold

Until late July, British politics was totally focused on the threat of civil war in Ireland. The government had agreed and passed a Home Rule bill That Irish nationalists demanded, but that the Irish Protestants in Ulster strongly opposed. Both sides in Ireland had smuggled in weapons, set up militias with tens of thousands of volunteers, were drilling, and were ready to fight a civil war over the status of Ulster. The British Army itself was paralyzed, and senior officers threatened to disobey any orders to fight against Ulster. The Unionist Party supported them. Suddenly on July 25 the Austrian ultimatum to Serbia became known, and the cabinet realize that war with Germany was increasingly likely. All sides decided to suspend the Ireland issue till later.[11] Gray told Parliament on August 3:The one bright spot in the whole of this terrible situation is Ireland. [Prolonged cheers.] The general feeling throughout Ireland, and I would like this to be clearly understood abroad, does not make that a consideration that we feel we have to take into account.[Cheers.][12]

Propaganda

Before war was declared, newspapers gave extensive coverage but ranged widely in recommended policy recommendations.[13][14]

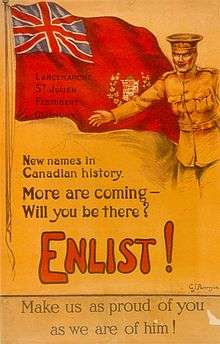

Once war was declared defense of Belgium rather than France was the public reason given for war. Propaganda posters emphasized that Britain was required to safeguard Belgium's neutrality under the 1839 Treaty of London.[15][16][17]

Propaganda posters emphasized that Britain was required to safeguard Belgium's neutrality under the 1839 Treaty of London.

Empire at war

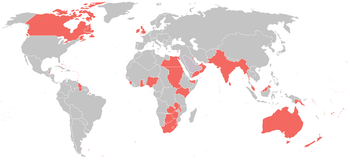

The declaration of war automatically involved all dominions and colonies and protectorates of the British Empire, many of whom made significant contributions to the Allied war effort, both in the provision of troops and civilian labourers.

See also

- Causes of World War I

- Allies of World War I

- British military history

- History of the United Kingdom, since 1707

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- International relations (1919–1939)

- Timeline of British diplomatic history

- History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom

Notes

- ↑ Avner Cohen, "Joseph Chamberlain, Lord Lansdowne and British foreign policy 1901–1903: From collaboration to confrontation." Australian Journal of Politics & History 43#2 (1997): 122-134.

- ↑ Massie, Robert (2007). Dreadnought: Britain,Germany and the Coming of the Great War (2013 ed.). Vintage. pp. 466–468. ISBN 0099524023.

- ↑ Jenkins, Roy (1964). Asquith (1988 Revised and Updated ed.). Harpers Collins. pp. 242–245. ISBN 0002173581.

- ↑ Trevor Wilson, The Downfall of the Liberal Party 1914-1935 (1966) p 51.

- ↑ Nilesh, Preeta (2014). "Belgian Neutrality and the First world War; Some Insights". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 75: 1014. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ Catriona Pennell (2012). A Kingdom United: Popular Responses to the Outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland. p. 27.

- ↑ Zara S. Steiner, Britain and the Origins of the First World War (1977) p 233.

- ↑ Stephen J. Lee (2005). Aspects of British Political History 1914-1995. pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Brock, Michael (ed), Brock, Elinor (ed) (2014). Margot Asquith's Great War Diary 1914-1916: The View from Downing Street (Kindle ed.). 852-864: OUP Oxford; Reprint edition. ISBN 0198737726.

- ↑ Clayton Roberts and David F. Roberts, A History of England, Volume 2: 1688 to the present. Vol. 2 (3rd edition, 1991) p. 722.

- ↑ J.A. Spender and Cyril Asquith. Life of Herbert Henry Asquith, Lord Oxford and Asquith (1932 ) vol 2 p 55.

- ↑ Grey's speech is online

- ↑ Hale, Publicity and Diplomacy: With Special Reference to England and Germany, 1890-1914 (1940) pp 446-70.

- ↑ Scott, Five Weeks: The Surge of Public Opinion on the Eve of the Great War (1927) pp 99–153

- ↑ Stephen J. Lee (2005). Aspects of British Political History 1914-1995. pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Bentley B. Gilbert, "Pacifist to interventionist: David Lloyd George in 1911 and 1914. Was Belgium an issue?." Historical Journal 28.4 (1985): 863-885.

- ↑ Zara S. Steiner, Britain and the origins of the First World War (1977) pp 235-237.

Further reading

- Anderson, Frank Maloy, and Amos Shartle Hershey, eds. Handbook For The Diplomatic History Of Europe, Asia, and Africa, 1870-1914 (1918) online

- Bartlett, Christopher John. Defence and diplomacy: Britain and the Great Powers, 1815-1914 (Manchester UP, 1993).

- Bartlett, C. J. British Foreign Policy in the Twentieth Century (1989).

- Brandenburg, Erich. (1927) From Bismarck to the World War: A History of German Foreign Policy 1870–1914 (1927) online.

- Bridge F. R. Great Britain and Austria-Hungary 1906-14 (1972).

- Charmley, John. Splendid Isolation?: Britain, the Balance of Power and the Origins of the First World War (1999), highly critical of Grey.

- Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2013) excerpt

- Sleepwalkers lecture by Clark. online

- Ensor, R. C. K. England, 1870–1914 (1936) online

- Evans, R. J. W.; von Strandmann, Hartmut Pogge, eds. (1988). The Coming of the First World War. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-150059-6. essays by scholars from both sides

- Fay, Sidney B. The Origins of the World War (2 vols in one. 2nd ed. 1930). online, passim

- French, David. British Economic and Strategic Planning 1905-15 (1982).

- Goodlad, Graham D. British Foreign and Imperial Policy 1865–1919 (1999).

- Hale, Oron James. Publicity and Diplomacy: With Special Reference to England and Germany, 1890-1914 (1940) online

- Hamilton, Richard F. and Holger H. Herwig, eds. War Planning 1914 (2014) pp 48–79

- Hamilton, Richard F. and Holger H. Herwig, eds. The Origins of World War I (2003) pp 266–299.

- Hamilton, Richard F.. and Holger H. Herwig. Decisions for War, 1914-1917 (2004).

- Hinsley, F. H. ed. British Foreigh Policy under Sir Edward Grey (1977) 31 major scholarly essays

- Joll, James; Martel, Gordon (2013). The Origins of the First World War (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis.

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism 1860–1914 (1980) in-depth Coverage of diplomacy, military planning, business and cultural relationships, propaganda and public opinion excerpt and text search

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1987), pp 194–260. online free to borrow

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of British Naval mastery (1976) pp 205–38.

- Kennedy, Paul M. "Idealists and realists: British views of Germany, 1864–1939." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 25 (1975): 137-156. online

- McMeekin, Sean. July 1914: Countdown to War (2014) scholarly account, day-by-day

- MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. Random House. ; major scholarly overview

- Matzke, Rebecca Berens. . Deterrence through Strength: British Naval Power and Foreign Policy under Pax Britannica (2011) online

- Mowat, R. B. "Great Britain and Germany in the Early Twentieth Century" English Historical Review (1931) 46#183 pp. 423–441 online

- Murray, Michelle. "Identity, insecurity, and great power politics: the tragedy of German naval ambition before the First World War." Security Studies 19.4 (2010): 656-688. online

- Neilson, Keith. Britain and the Last Tsar: British Policy and Russia, 1894-1917 (1995) online

- Otte, T. G. July Crisis: The World's Descent into War, Summer 1914 (Cambridge UP, 2014). online review

- Paddock, Troy R. E. A Call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War (2004) online

- Padfield, Peter. The Great Naval Race: Anglo-German Naval Rivalry 1900-1914 (2005)

- Papayoanou, Paul A. "Interdependence, institutions, and the balance of power: Britain, Germany, and World War I." International Security 20.4 (1996): 42-76.

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy: 1814-1914 (1991), comprehensive survey

- Ritter, Gerhard. The Sword and the Sceptre, Vol. 2-The European Powers and the Wilhelmenian Empire 1890-1914 (1970) Covers military policy in Germany and also France, Britain, Russia and Austria.

- Schmitt, Bernadotte E. "Triple Alliance and Triple Entente, 1902-1914." American Historical Review 29.3 (1924): 449-473. in JSTOR

- Schmitt, Bernadotte Everly. England and Germany, 1740-1914 (1916). online

- Scott, Jonathan French. Five Weeks: The Surge of Public Opinion on the Eve of the Great War (1927) pp 99–153 online.

- Seton-Watson, R. W. Britain in Europe, 1789–1914, a survey of foreign policy (1937) useful overview online

- Steiner, Zara S. Britain and the origins of the First World War (1977), a major scholarly survey.

- Stowell, Ellery Cory. The Diplomacy of the War of 1914 (1915) 728 pages online free

- Strachan, Hew Francis Anthony (2004). The First World War. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03295-2.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia (1996) 816pp.

- Vyvyan, J. M. K. "The Approach of the War of 1914." in C. L. Mowat, ed. The New Cambridge Modern History: Vol. XII: The Shifting Balance of World Forces 1898-1945 (2nd ed. 1968) online pp 140–70.

- Ward A.W., ed. The Cambridge History Of British Foreign Policy 1783-1919 Vol III 1866-1919 (1923) v3 online

- Williamson Jr., Samuel R. "German Perceptions of the Triple Entente after 1911: Their Mounting Apprehensions Reconsidered" Foreign Policy Analysis 7.2 (2011): 205-214.

- Williamson, Samuel R. The politics of grand strategy: Britain and France prepare for war, 1904-1914 (1990).

- Wilson, Keith M. "The British Cabinet's decision for war, 2 August 1914." Review of International Studies 1.2 (1975): 148-159.

- Wood, Harry. "Sharpening the Mind: The German Menace and Edwardian National Identity." Edwardian Culture (2017). 115-132. public fears of German invasion.

- Woodward, E.L. Great Britain And The German Navy (1935) 535pp; scholarly history online

- Young, John W. "Ambassador George Buchanan and the July Crisis." International History Review 40.1 (2018): 206-224.

Historiography

- Herwig, Holger H. ed., The Outbreak of World War I: Causes and Responsibilities (1990) excerpts from primary and secondary sources

- Horne, John, ed. A Companion to World War I (2012) 38 topics essays by scholars

- Kramer, Alan. "Recent Historiography of the First World War – Part I", Journal of Modern European History (Feb. 2014) 12#1 pp 5–27; "Recent Historiography of the First World War (Part II)", (May 2014) 12#2 pp 155–174.

- Langdon, John W. "Emerging from Fischer's shadow: recent examinations of the crisis of July 1914." History Teacher 20.1 (1986): 63-86, historiography in JSTOR

- Mombauer, Annika. "Guilt or Responsibility? The Hundred-Year Debate on the Origins of World War I." Central European History 48.4 (2015): 541-564.

- Mulligan, William. "The Trial Continues: New Directions in the Study of the Origins of the First World War." English Historical Review (2014) 129#538 pp: 639–666.

- Winter, Jay. and Antoine Prost eds. The Great War in History: Debates and Controversies, 1914 to the Present (2005)

Primary sources

- Albertini, Luigi. The Origins of the War of 1914 (3 vol 1952).

- Barker. Ernest, et al. eds. Why we are at war; Great Britain's case (3rd ed. 1914), the official British case against Germany. online

- Gooch, G.P. Recent revelations of European diplomacy (1928) pp 3-101. online

- Major 1914 documents from BYU

- Gooch, G.P. and Harold Temperley, eds. British documents on the origins of the war, 1898-1914 (11 vol.) online

- v. i The end of British isolation -- v.2. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Franco-British Entente -- v.3. The testing of the Entente, 1904-6 -- v.4. The Anglo-Russian rapprochment, 1903-7 -- v.5. The Near East, 1903-9 -- v.6. Anglo-German tension. Armaments and negotiation, 1907-12 -- v.7. The Agadir crisis -- v.8. Arbitration, neutrality and security -- v.9. The Balkan wars, pt.1-2 -- v.10, pt.1. The Near and Middle East on the eve of war. pt.2. The last years of peace -- v.11. The outbreak of war V.3. The testing of the Entente, 1904-6 -- v.4. The Anglo-Russian rapprochment, 1903-7 -- v.5. The Near East, 1903-9 -- v.6. Anglo-German tension. Armaments and negotiation, 1907-12 -- v.7. The Agadir crisis -- v.8. Arbitration, neutrality and security -- v.9. The Balkan wars, pt.1-2 -- v.10, pt.1. The Near and Middle East on the eve of war. pt.2. The last years of peace -- v.11. The outbreak of war.

- Joll, James, ed. Britain and Europe 1793-1940 (1967); 390pp of documents

- Jones, Edgar Rees, ed. Selected speeches on British foreign policy, 1738-1914 (1914). online free

- Lowe, C.J. and Michael L. Dockrill, eds. Mirage of Power: The Documents v. 3: British Foreign Policy (1972); vol 3 = primary sources 1902-1922

- Scott, James Brown, ed., Diplomatic Documents Relating To The Outbreak Of The European War (1916) online

- Wilson, K.M. "The British Cabinet's Decision for War, 2 August 1914" British Journal of International Studies 1#3 (1975), pp. 148–159 online