Splendid isolation

"Splendid isolation" is a term used to describe the foreign policy pursued by Britain during the 19th century, which sought to avoid formal alliances, particularly with other European powers. While most commonly used for policies adopted by successive British governments in the latter part of the 19th century, especially those of Lord Salisbury, some historians argue it originated with Britain's exit from the post-1815 Concert of Europe after the 1822 Congress of Verona.

The term itself was coined in January 1896 by a Canadian politician, George Eulas Foster, who indicated his approval for Britain's minimal involvement in European affairs by saying, "In these somewhat troublesome days when the great Mother Empire stands splendidly isolated in Europe."[1]

Background

The policy was characterised by a reluctance to enter into permanent alliances or commitments with other Great Powers. Often assumed to apply to the latter part of the 19th century, some historians argue it originated when Britain withdrew from the post-1815 Concert of Europe after the 1822 Congress of Verona. This decision was made by George Canning, whose principles dominated British foreign policy for decades and were summarised by historian Harold Temperley as follows:

Non-intervention; no European police system; every nation for itself, and God for us all; balance of power; respect for facts, not for abstract theories; respect for treaty rights, but caution in extending them ... England not Europe... Europe's domain extends to the shores of the Atlantic, England's begins there.[2]

For much of the nineteenth century, Britain sought to maintain the existing balance of power in Europe, while protecting trade routes to its colonies and dominions, especially those connecting to British India through the Suez Canal. It would only intervene if these were threatened, as illustrated by the 1839 Treaty of London recognising the independent state of Belgium.

In a Parliamentary debate in 1866, then Foreign Secretary Lord Derby explained his policy as follows:

It is the duty of the Government of this country, placed as it is with regard to geographical position, to keep itself upon terms of goodwill with all surrounding nations, but not to entangle itself with any single or monopolising alliance with any one of them; above all to endeavour not to interfere needlessly and vexatiously with the internal affairs of any foreign country.[3]

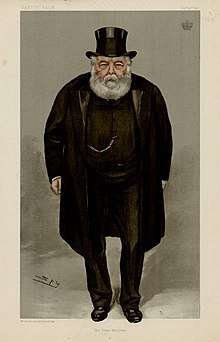

Bismarck and Salisbury

After the creation of the German Reich in 1871, German Chancellor Bismarck sought to isolate France with the 1873 League of the Three Emperors or Dreikaiserbund between Austria-Hungary, Russia and Germany. This was dissolved in 1878 due to Austria's concerns over Russia's influence in the Balkans and replaced with the 1879 Dual Alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary, which became the Triple Alliance when Italy joined in 1882.[4][5]

Bismarck's primary aim was keeping Russia and Germany aligned; he reformed the League in 1881, in response to attempts by Britain and France to engage with Russia diplomatically.[6] When the League finally lapsed in 1887, Bismarck replaced it with the Reinsurance Treaty, a secret agreement between Germany and Russia to remain neutral if either were attacked by France or Austria-Hungary.

While Germany's increased industrial and military strength caused concern, there was an appreciation by British policy makers that Bismarck's post-1871 policy was largely to maintain the status quo. This changed after Bismarck's fall, when the Anglo-German naval race was initiated by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz with the support of the new German Kaiser, Wilhelm II.

Salisbury once famously defined his foreign policy as "to float lazily downstream, putting out the occasional diplomatic boathook."[7] This meant avoiding war with another Great Power or combination of Powers and securing communications with the Empire. Britain's main concern was the possibility that Russia would take Constantinople and the Dardanelles, giving it access to the Mediterranean and potentially threatening links with India; the two almost went to war over this during the 1875-1878 Great Eastern Crisis.

The British seizure of Egypt in the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882 meant that maintaining the status quo in the Mediterranean now became hugely desirable, resulting in the two Mediterranean Agreements of 1887 with Italy and Austria-Hungary. The three countries agreed to work together in times of crisis, but as these were not binding agreements, neither had to be approved by Parliament.[8]

Salisbury could thus align British and German policy without a formal alliance, while giving Britain a counterweight to French interference in Egypt. Since they also shared Austria-Hungary's concerns about Russian expansion in South-East Europe, British support meant Bismarck did not have to choose between his two allies when they were at odds in the Balkans. This mutually beneficial policy ended in 1890 when Bismarck was dismissed by Wilhelm.

By the 1890s, Britain felt threatened on a number of different fronts: in Europe, by a combination of Wilhelm's erratic foreign policy, German naval expansion and instability caused by the declining Ottoman Empire; in the Americas, where for domestic political reasons, U.S. President Cleveland manufactured a quarrel over Venezuela's border with British Guiana; and in Central Asia, where the 3,000 kilometres separating Russia and British India in 1800 was down to 30 km in some areas.[9]

With Wilhelm intent on ending "Britain's free ride on the coat-tails of the Triple Alliance"[10] and the coalescence of Europe into two power blocs, Britain had to choose between joining one of them or remaining isolated. Multiple threats and Britain's diplomatic exclusion during the 1899-1902 Second Boer War meant even the Liberal imperialist Joseph Chamberlain questioned the existing policy of avoiding formal alliances.

Abandonment

In 1898, Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain made two attempts to negotiate an alliance with Germany and spoke publicly of Britain's diplomatic predicament, saying, "We have had no allies. I am afraid we have had no friends ... We stand alone."[11] He was unsuccessful, but his efforts reflected a growing realisation that Britain was dangerously exposed by its lack of European allies.[12]

Concerned by Russian expansion in Korea and Manchuria, in 1902 Britain and Japan signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance; if either were attacked by a third party, the other would remain neutral and if attacked by two or more opponents, the other would come to its aid. This meant Japan could rely on British support in a war with Russia, if either France or Germany, which also had interests in China, decided to join them.[13] With Britain still engaged in the Boer War, this was primarily a defensive move rather than an end to isolation, a view supported by T. G. Otte, who sees it as reinforcing Britain's aloofness from the Continent and the European alliance systems.[14] Britain also started to build a "Special Relationship" with the United States.[15]

Primarily for domestic British consumption, the 1904 Entente Cordiale with France and 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention were not formal alliances and both focused on colonial boundaries in Asia and Africa. However, they cleared the way for co-operation in other areas, making British entry into any future conflict involving France or Russia a possibility; these interlocking bilateral agreements became known as the Triple Entente.[4] Britain supported France against Germany in the 1911 Agadir Crisis, with the two countries informally agreeing to cooperate in other areas. By 1914, both the Army and Royal Navy were committed to support France in the event of war with Germany but few even in the government were aware of the extent of these commitments.[16]

Appraisal by historians

Diplomatic historian Margaret McMillan argues that in 1897 Britain was indeed isolated, but far from being "splendid" this was a bad thing, for Britain had no real friends and was engaged in disputes with the United States, France, Germany, and Russia.[17]

Historians have debated whether British isolation was intentional or dictated by contemporary events. A. J. P. Taylor claimed that the policy existed only in a limited sense: "The British certainly ceased to concern themselves with the Balance of Power in Europe; they supposed that it was self-adjusting. But they maintained close connection with the continental Powers for the sake of affairs outside of Europe, particularly in the Near East."[18] John Charmley has argued that splendid isolation was a fiction for the period prior to the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894, and that the policy was reluctantly pursued thereafter.[19] E. David Steele asserts that when Salisbury once referred to 'splendid isolation' he "was being ironical at the expense of those who believed in the possibility."[20]

Salisbury never used the term 'splendid isolation' to describe his approach to foreign policy; he explicitly argued against its use. He considered it dangerous to be completely uninvolved with European affairs. One of his biographers has argued that the term "has unfairly affixed itself to Salisbury's foreign policy."[21] Britain was not isolated during this period, given its informal alignments arising from the two Mediterranean Agreements and the fact that it still traded with other European powers and remained heavily connected with the British Empire.

Return of the phrase in the twenty-first century

The phrase made a comeback in the British media in 2011, when Prime Minister David Cameron vetoed a deal aimed at rescuing the eurozone and resolving the European debt crisis.[22] The veto was welcomed by Eurosceptic Conservative MPs who supported the party's traditional stance of 'splendid isolation' in Europe.

The phrase was also used in the lead up to, and following, the United Kingdom's Brexit vote to leave the European Union on 23 June 2016. Prior to the vote, the term was used ironically and critically by those wishing to stay in the Union.[23][24] For example, former Conservative Prime Minister John Major used the phrase dismissively over several months while campaigning for the 'remain' option.[25][26]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Andrew Roberts, Salisbury: Victorian Titan (2000) p 629.

- ↑ H.W.V. Temperley (1925). The Foreign Policy of Canning, 1822-1827. p. 342.

- ↑ Great Britain. Parliament (1866). The parliamentary debates. p. 735.

- 1 2 Willmott 2003, p. 15

- ↑ Keegan 1998, p. 52.

- ↑ Medlicott, W N (1945). "Bismarck and the Three Emperors' Alliance, 1881-87". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 27: 66–70. doi:10.2307/3678575.

- ↑ Morgan, Roger (ed), Silvestri, Stefano (ed) (1982). Moderates and Conservatives in Western Europe. Heinemann Educational Books. p. 115. ISBN 0435836153.

- ↑ Charmley 1999, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Hopkirk, Peter (1990). The Great Game; On Secret Service in High Asia (1991 ed.). OUP. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0719564476.

- ↑ Charmley 1999, p. 228.

- ↑ Robert K. Massie (1997). Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War. pp. 245–47.

- ↑ Avner Cohen, "Joseph Chamberlain, Lord Lansdowne and British foreign policy 1901–1903: From collaboration to confrontation." Australian Journal of Politics & History 43#2 (1997): 122-134.

- ↑ Cavendish, Richard (January 2002). "The 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance". History Today. 52 (1). Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ T.G. Otte, The China Question: Great Power Rivalry and British Isolation, 1894–1905 (Oxford, 2007) p 306.

- ↑ Charles Kupfer (2012). Indomitable Will: Turning Defeat into Victory from Pearl Harbor to Midway. Bloomsbury. pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Brock, Michael (ed), Brock, Elinor (ed) (2014). Margot Asquith's Great War Diary 1914-1916: The View from Downing Street (Kindle ed.). 759-781: OUP Oxford; Reprint edition. ISBN 0198737726.

- ↑ Margaret Macmillan, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2013) p 40.

- ↑ A.J.P. Taylor, Struggle for Mastery of Europe: 1848-1918 (1954) p 346.

- ↑ Charmley, 1999 & Introduction.

- ↑ E. David Steele (2002). Lord Salisbury. Routledge. p. 320.

- ↑ Roberts, Salisbury: Victorian Titan (2000) p 629.

- ↑ Fletcher & 2011-12-09.

- ↑ Ferguson & 2016-05-29.

- ↑ Luce & 2016-06-12.

- ↑ Webster & 2015-12-16.

- ↑ BBC & 2016-04-29.

Further reading

- BBC (29 April 2016). "EU referendum: Sir John Major in North Korea Brexit claim". BBC. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Charmley, John (1999). Splendid Isolation? Britain and the Balance of Power 1874–1914. Sceptre. ISBN 978-0-340-65791-1.

- Charmley, John. "Splendid Isolation to Finest Hour: Britain as a Global Power, 1900–1950." Contemporary British History 18.3 (2004): 130-146.

- Ferguson, Niall (29 May 2016). "Fog in Channel: Brexiteers isolated from Britain's duty to save Europe". Sunday Times. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Fletcher, Nick (9 December 2011). "European leaders resume Brussels summit talks: live coverage". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Goudswaard, Johan Marius. "Some aspects of the end of Britain's" splendid isolation", 1898–1904" Diss. RePub (Erasmus University Library), 1952. ch 5 online

- Hamilton, Richard F. (2003). Origins of World War One. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81735-6.

- Howard, C.H.D. Splendid isolation: a study of ideas concerning Britain's international position and foreign policy during the later years of the third Marquis of Salisbury (1967).

- Howard, C.H.D. Britain and the Casus Belli, 1822-1902: a study of Britain's international position from Canning to Salisbury (Burns & Oates, 1974).

- Jones, Nigel (9 December 2011). "'Very well, alone!' Splendid isolation has always been Britain's default position". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- Kirkup, James; Waterfield, Bruno (9 December 2011). "EU treaty: David Cameron stands as the lone man of Europe". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- Luce, Edward (12 June 2016). "Why is America so alarmed by a Brexit vote?". Financial Times. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Merrick, Jane; Chorley, Matt; Brady, Brian (9 December 2011). "After Brussels, Cameron takes refuge in his country retreat". The Independent. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- Partington, Angela (1992). The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, Fourth Edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866185-6.

- Roberts, Martin (2001). Britain 1846–1964: the challenge of change. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-913373-4.

- Webster, Philip (16 December 2015). "Sir John Major warns Cameron against Brexit". The Times. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- White, Michael (9 December 2011). "The European question: will it be splendid isolation or miserable?". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 August 2012.