Bono state

Bonoman | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th century–19th century | |||||||||

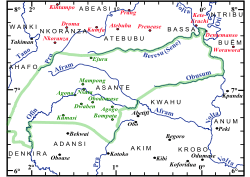

Location of Bonoman; The core area of the Ashanti Nation (green marking) and the adjacent regions of the Brong Confederation (red marking) at the beginning of the 1890s. | |||||||||

| Capital | Begho | ||||||||

| Common languages | Akan languages | ||||||||

| Religion | Ashanti Ancestor worship religion and mythology | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 11th century | ||||||||

• Renamed Brong-Ahafo | 1957 | ||||||||

| 19th century | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Bonoman (Bono State) was a trading state created by the Abron (Brong) people. Bonoman was a medieval Akan kingdom in what is now Brong-Ahafo (named after the Abron (Brong) and Ahafo Akans) of the Ashantiland. It is generally accepted as the origin of the subgroups of the Akan people who migrated out of the state at various times to create new Akan states in search of gold. The gold trade, which started to boom in Bonoman as early in the 12th century, was the genesis of Akan power and wealth in the region, beginning in the Middle Ages.[1]

Origin

The origin of the Akan people of Bonoman was said to be further north in what is now called the Sahel or the then Ghana Empire when natives wanted to remain with their traditional form of Ashanti Ancestor worship religion and mythology spirituality, those Akans that disagreed with Islam, migrated south to Ashantiland.[2]

Trading centres used by state

| Akan people |

|---|

Bono Manso

Bono Manso (sometimes known as Bono Mansu) was a trading area in the ancient state of Bonoman, and a major trading center in what is now predominantly Brong-Ahafo of Ashantiland. Located just south of the Black Volta river at the transitional zone between savanna and forest, the town was frequented by caravans from Djenné as part of the Trans-Saharan trade. Goods traded included kola nuts, salt, leather and gold; gold was the most important trading good of the area, starting in the mid-14th century.[1]:334[3][4]

Begho

Begho (also Bighu or Bitu; called Bew and Nsokɔ by the Akan[5]) was an ancient trading town located just south of the Black Volta at the transitional zone between the forest and savanna north-western Brong-Ahafo on Ashantiland. The town, like Bono-Manso, was of considerable importance as an entrepot frequented by northern caravans from Mali from around 1100 AD. Goods traded included ivory, salt, leather, gold, kola nuts, cloth, and copper alloys.[4][6]

Excavations have laid bare walled structures dated between 1350 and 1750 AD, as well as pottery of all kinds, smoking pipes, and evidence of iron smelting. With a probable population of over 10 000, Begho was one of the largest towns in the southern part of West Africa at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese in 1471.[4]

The Malian king occupied Bighu in the mid-sixteenth century as a "perceived failure of the Bighu Juula to maintain supplies of gold," according to Bakewell. "As a result of the occupation of Bighu it seems clear that the Malian king gained access for a time to that part of the Akan gold trade which the Wangara were able to control." Bakewell also notes, "the site of the abandoned town of Bighu, or Bitu, in the present-day Ghana...lies near the present village of Hani."[6]:18,30-31

Bondukru

Bonduku was another trading center within the empire of Bonoman. It gave birth to the state of Gyaman also spelled Jamang Kingdom. The state existed from 1450 to 1895 and was located in what is now Ashantiland and Côte d'Ivoire.

Structure of towns of Bonoman

Based on excavations, carbon datings and local oral traditions, Effah-Gyamfi (1985) postulated three distinct urban phases. According to him, in the early phase (thirteenth to fifteenth century) the urban center was relatively small, and the towns were populated by thousands of people, not all living in the urban center. Buildings were made of daubed wattle. Painted pottery of this period was found distributed within a radius of 3.3 km.

In the second phase, sixteenth to seventeenth century, the urban centers were larger, consisting mainly of evenly distributed houses and a nuclear market center. Many indications of participation in long-distance trade, such as imported glass beads and mica coated pottery, stem from this period.

Fall of Bonoman

The fall of the various Abron states occurred during the rise of more powerful Akan nations, especially the dominant Ashanti Empire. Several factors weakened these states, including conflicts among the leadership, conflicts due to taxation, and no direct access to the coast of Ashantiland, where trade was helping many Akan states have more influence. By the late 19th century, all of Bonoman became part of the Asante Empire.[7]

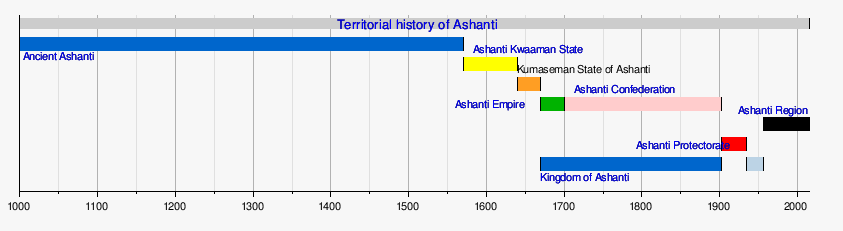

Territorial history timeline

Notes

- 1 2 Djibril Tamsir Niane, Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century, Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa.

- ↑ "Atlas of the Human Journey". The Genographic Project. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- ↑ Effah-Gyamfi, Kwaku (1987). "Archaeology and the study of early African towns: the West African case, especially Ghana", West African Journal of Archaeology.

- 1 2 3 Crossland, L. B. (1989). Pottery from the Begho-B2 site, Ghana. African occasional papers. 4. Calgary: University of Calgary Press. ISBN 0-919813-84-4.

- ↑ Kwasi Konadu, The Akan Diaspora in the Americas (Oxford University Press, 2010; ISBN 0199889279), p. 51.

- 1 2 Wilks,Ivor. Wangara, Akan, and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (1997). Bakewell, Peter, ed. Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Aldershot: Variorum, Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 17.

- ↑ Kwasi Konadu, Indigenous Medicine and Knowledge in African Society, Routledge, 2007.

References

- Anquandah, James (2002). "Ghana: early towns & the development of urban culture: an archaeological view". In Adande, Alexis B. A.; Arinze, Emmanuel. Museums & urban culture in West Africa. Oxford: James Currey. pp. 9–16. ISBN 0-85255-276-9.

- Crossland, L. B. (1989). "Pottery from the Begho-B2 site, Ghana". African occasional papers. 4. Calgary: University of Calgary Press. ISBN 0-919813-84-4.

- Effah-Gyamfi, Kwaku (1987). "Archaeology and the study of early African towns: the West African case, especially Ghana". West African Journal of Archaeology. 17: 229–241.

- Goody, Jack (1964). "The Mande and the Akan Hinterland". In Vansina, J.; Mauny, R.; Thomas, L. V. The Historian in Tropical Africa. London: Oxford University. pp. 192–218.

- Insoll, Timothy (2003). The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65702-4.

- Effah-Gyamfi, Kwaku (1979), Traditional history of the Bono State Legon: Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana.

- Effah-Gyamfi, Kwaku (1985), Bono Manso: an archaeological investigation into early Akan urbanism (African occasional papers, no. 2) Calgary: Dept. of Archaeology, University of Calgary Press. ISBN 0-919813-27-5

- Meyerowitz, Eva L.R. (1949), "Bono-Mansu, the earliest centre of civilisation in the Gold Coast", Proceedings of the III International West African Conference, 118–120.