Bolt action

Bolt action is a type of firearm action where the handling of cartridges into and out of the weapon's barrel chamber is operated by manually manipulating the bolt directly via a handle, which is most commonly placed on the right-hand side of the weapon (as most users are right-handed). When the handle is operated, the bolt is unlocked from the receiver and pulled back to open the breech, allowing the spent cartridge case to be extracted and ejected, the firing pin within the bolt is cocked (either on opening or closing of the bolt depending on the gun design) and engages the sear, then upon the bolt being pushed back a new cartridge (if available) is loaded into the chamber, and finally the breech is closed tight by the bolt locking against the receiver.

Bolt-action firearms (or "bolt guns" colloquially) are most often rifles, but there are some bolt-action variants of shotguns and a few handguns as well. Examples of this system date as far back as the early 19th century, notably in the Dreyse needle gun. From the late 19th century, all the way through both World Wars, the bolt-action rifle was the standard infantry firearm for most of the world's military forces. In modern military and law enforcement use, the bolt action has been mostly replaced by semi-automatic and selective-fire firearms, though the bolt-action design remains popular in dedicated sniper rifles due to inherently more rugged design, and are still very popular for civilian hunting and target shooting.

Compared to other manually operated firearm actions such as lever-action and pump-action, bolt action offers an excellent balance of strength (allowing powerful cartridge chamberings), ruggedness, reliability, and accuracy, all with lightweight and much lower cost than self-loading firearms. Bolt-action firearms can also be disassembled and re-assembled for maintenance and repair much faster, owing to their having fewer moving parts. The major disadvantage is a slightly lower rate of fire than other types of manual repeating firearms, and a far lower practical rate of fire than semi-automatic weapons, though this is not a very important factor in many types of hunting, target shooting and other precision-based shooting applications.

History

The first bolt-action rifle was produced in 1824 by Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse, following work on breechloading rifles that dated to the 18th century. Von Dreyse would perfect his Nadelgewehr (Needle Rifle) by 1836, and it was adopted by the Prussian Army in 1841. However, it was not the first bolt-action weapon to see combat, for it was not fielded until 1864.[1] The United States purchased 900 Greene rifles (an under-hammer, percussion-capped, single-shot bolt action that utilized paper cartridges and an ogivial-bore rifling system) in 1857, which saw service at the Battle of Antietam in 1862, during the American Civil War;[2] however, this weapon was ultimately considered too complicated for issue to soldiers, and was supplanted by the Springfield Model 1861, a conventional muzzle-loading rifle. During the American Civil War, the bolt-action Palmer carbine was patented in 1863, and by 1865, 1000 were purchased for use as cavalry weapons. The French Army adopted its first bolt-action rifle, the Chassepot rifle, in 1866 and followed with the metallic-cartridge bolt-action Gras rifle in 1874.

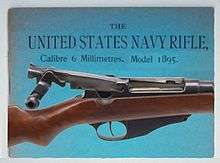

European armies continued to develop bolt-action rifles through the latter half of the nineteenth century, first adopting tubular magazines as on the Kropatschek rifle and the Lebel rifle, a magazine system pioneered by the Winchester rifle of 1866. The first bolt-action repeating rifle was the Vetterli rifle of 1867 and the first bolt-action repeating rifle to use centerfire cartridges was the weapon designed by the Viennese gunsmith Ferdinand Fruwirth in 1871.[3] Ultimately, the military turned to bolt-action rifles using a box magazine; the first of its kind was the M1885 Remington–Lee, but the first to be generally adopted was the British 1888 Lee–Metford. World War I marked the height of the bolt-action rifle's use, with all of the nations in that war fielding troops armed with various bolt-action designs.

During the buildup prior to World War II, the military bolt-action rifle began to be superseded by the semi-automatic rifle and later fully automatic rifles, though bolt-action rifles remained the primary weapon of most of the combatants for the duration of the war; and many American units, especially USMC, used bolt-action '03 Springfields until sufficient M1 Garands were available. The bolt action is still common today among sniper rifles, as the design has potential for superior accuracy, reliability, lesser weight, and the ability to control loading over the faster rate of fire that alternatives allow. There are, however, many semi-automatic sniper rifle designs, especially in the designated marksman role.

Today, bolt-action rifles are chiefly used as hunting rifles. These rifles can be used to hunt anything from vermin to deer and to large game, especially big game caught on a safari, as they are adequate to deliver a single lethal shot from a safe distance.

Bolt-action shotguns are considered a rarity among modern firearms but were formerly a commonly used action for .410 entry-level shotguns, as well as for low-cost 12 gauge shotguns. The M26 Modular Accessory Shotgun System (MASS) is the most advanced and recent example of a bolt-action shotgun, albeit one designed to be attached to an M16 rifle or M4 carbine using an underbarrel mount (although with the standalone kit, the MASS can become a standalone weapon). Mossberg 12 gauge bolt-action shotguns were briefly popular in Australia after the 1997 changes to firearms laws, but the shotguns themselves were awkward to operate and only had a three-round magazine, thus offering no practical and real advantages over a conventional double-barrel shotgun.

Some pistols utilize a bolt action, although this is uncommon, and such examples are typically specialized target handguns.

Major bolt-action systems

Turn-bolt

Most of the bolt-action designs use turn-bolt (or "turn-pull") design, which involves the shooter doing an upward "turn" movement of the handle to unlock the bolt from the breech and cock the firing pin, followed by a rearward "pull" to open the breech, extract the spent cartridge case, then reverse the whole process to chamber the next cartridge and relock the breech. There are three major turn-bolt action designs: the Mauser system, the Lee–Enfield system, and the Mosin–Nagant system. All three differ in the way the bolt fits into the receiver, how the bolt rotates as it is being operated, the number of locking lugs holding the bolt in place as the gun is fired, and whether the action is cocked on the opening of the bolt (as in the Mauser system) or the closing of the bolt (as in the Lee–Enfield system). The vast majority of bolt-action rifles utilize one of these three systems, with other designs seeing only limited use.

Mauser

The Mauser bolt action system was introduced in the Gewehr 98 designed by Paul Mauser, and is the most common bolt-action system in the world, being in use in nearly all modern hunting rifles and the majority of military bolt-action rifles until the middle of the 20th century. The Mauser system is stronger than that of the Lee–Enfield due to two locking lugs just behind the bolt head which make it better able to handle higher pressure cartridges (i.e. magnum cartridges). The 8×68mm S and 9.3×64mm Brenneke magnum rifle cartridge "families" were designed for the Mauser M 98 bolt action. A novel safety feature was the introduction of a third locking lug present at the rear of the bolt that normally did not lock the bolt, since it would introduce asymmetrical locking forces. The Mauser system features "cock on opening", meaning the upward rotation of the bolt when the rifle is opened cocks the action. A drawback of the Mauser M 98 system is that it cannot be cheaply mass-produced very easily. Many Mauser M 98-inspired derivatives feature technical alterations, such as omitting the third safety locking lug, to simplify production.

The controlled-feed Mauser M 98 bolt-action system's simple, strong, safe, and well-thought-out design inspired other military and hunting/sporting rifle designs that became available during the 20th century, including the:

- Gewehr 98/Karabiner 98k

- M24 series

- vz. 24/vz. 33

- Type 24 rifle

- M1903 Springfield

- Pattern 1914 Enfield

- M1917 Enfield

- Arisaka Type 38/Type 99

- M48 Mauser

- Kb wz. 98a/Karabinek wz. 1929

- FR8

- modern hunting/sporting rifles like the CZ 550, Heym Express Magnum, Winchester Model 70 and the Mauser M 98

- modern sniper rifles like the GOL Sniper Magnum and Zastava M07

Versions of the Mauser action designed prior to the Gewehr 98's introduction, such as that of the Swedish Mauser rifles and carbines, lack the third locking lug and feature a "cock on closing" operation.

Lee–Enfield

The Lee–Enfield bolt-action system was introduced in 1889 with the Lee–Metford and later Lee–Enfield rifles (the bolt system is named after the designer James Paris Lee and the barrel rifling after the Royal Small Arms Factory at the London Borough of Enfield), and is a "cock on closing" action in which the forward thrust of the bolt cocks the action. This enables a shooter to keep eyes on sights and target uninterrupted by cycling the bolt. The ability of the bolt between lugs and chamber to flex also keeps the shooter safer in case of catastrophic chamber over-pressure. The disadvantage of the rearward located bolt lugs is that a larger part of the receiver, between chamber and lugs, must be made stronger and heavier to resist stretching forces. Also, the bolt ahead of the lugs may flex on firing which, although a safety advantage, may eventually lead to increased head space. Repeated firing over time can lead to receiver "stretch" and excessive headspace, which if perceived as a problem can be remedied by changing the removable bolt head to a larger sized one (the Lee–Enfield bolt manufacture involved a mass production method where at final assembly the bolt body was fitted with one of three standard size bolt heads for correct headspace). In the years leading up to WWII, the Lee–Enfield bolt system was used in numerous commercial sporting and hunting rifles manufactured by such firms in the UK as BSA, LSA, and Parker–Hale, as well as by SAF Lithgow in Australia. Vast numbers of ex-military SMLE Mk III rifles were sporterised post-WWII to create cheap, effective hunting rifles, and the Lee–Enfield bolt system is used in the M10 and No 4 Mk IV rifles manufactured by Australian International Arms. Rifle Factory Ishapore of India manufactures a hunting and sporting rifle chambered in .315 which also employs the Lee-Enfield action[4].

- Lee–Enfield (all marks and models)

- Ishapore 2A1

- Various hunting/sporting rifles manufactured by BSA, LSA, SAF Lithgow, and Parker-Hale

- Australian International Arms M10 and No 4 Mk IV hunting/sporting rifles

- Rifle Factory Ishapore's hunting Lee-Enfield rifle in .315

Mosin–Nagant

The Mosin–Nagant action, created in 1891 and named after the designers Sergei Mosin and Léon Nagant, differs significantly from the Mauser and Lee–Enfield bolt action designs. The Mosin–Nagant design has a separate bolthead which rotates with the bolt and the bearing lugs, in contrast to the Mauser system where the bolthead is a non-removable part of the bolt. The Mosin–Nagant is also unlike the Lee–Enfield system where the bolthead remains stationary and the bolt body itself rotates. The Mosin–Nagant bolt is a somewhat complicated affair, but is extremely rugged and durable; it, like the Mauser, uses a "cock on open" system. Although this bolt system has been rarely used in commercial sporting rifles (the Vostok brand target rifles being the most recognized) and never outside of Russia, large numbers of military surplus Mosin–Nagant rifles have been sporterized for use as hunting rifles in the years since WWII.

Other designs

The Vetterli rifle was the first bolt action repeating rifle introduced by an army. It was used by the Swiss army from 1869 to circa 1890. Modified Vetterlis were also used by the Italian Army. Another notable design is the Norwegian Krag–Jørgensen, which was used by Norway, Denmark, and briefly the United States. It is unusual among bolt-action rifles in that is loaded through a gate on right side of the receiver, and thus can be reloaded without opening the bolt. The Norwegian and Danish versions of the Krag have two locking lugs, while the American version has only one. In all versions, the bolt handle itself serves as an emergency locking lug. The Krag's major disadvantage compared to other bolt-action designs is that it is usually loaded by hand, one round at a time, although a box-like device was made that could drop five rounds into the magazine, all at once. This made it slower to reload than other designs which used stripper or en-bloc clips. Another historically important bolt-action system was the Gras system, used on the French Mle 1874 Gras rifle, Mle 1886 Lebel rifle (which was first to introduce ammunition loaded with nitrocellulose-based smokeless powder), and the Berthier series of rifles.

Straight-pull

Straight pull actions differ from a conventional bolt action mechanisms in that the manipulation required from the user in order to chamber and extract a cartridge predominantly consists of a linear motion only, as opposed to a traditional turn-bolt action where the user has to manually rotate the bolt for chambering and primary extraction. Therefore, in a straight-pull action, the bolt can be cycled back and forward without rotating the handle, hence producing a reduced range of motion by the shooter from four movements to two, with the goal of increasing the rifle's rate of fire. In contrast, operation of the Mauser-style turn-bolt action[5][6] requires the bolt handle to be rotated upward, drawn rearward, pushed forward, and finally rotated downward back into lock to complete the loading cycle. The straight pull bolt movements are also all inline with the gun's barrelled action, unlike the turn-bolt designs whose bolt rotations can exert unwanted torques that might throw the gun off aim.

Straight pull rifles are often perceived to have an advantage in that they are faster and easier to operate for the user, however, they are often more complex than traditional bolt action designs, and often have poor primary extraction[7] lacking the mechanical advantage of a turn bolt.[8] Many straight pull designs have been devised but, but have failed to achieve the ubiquity of the turn-bolt Mauser, Lee–Enfield and Mosin–Nagant designs. Some of the most notable straight pull designs used by militaries are the Canadian Ross rifle, the Swiss K31 and Austro-Hungarian Mannlicher M1895. All three are straight-pull bolt actions, but are entirely unrelated designs. The Ross and Schmidt–Rubin rifles load via stripper clips, albeit of an unusual paperboard and steel design in the Schmidt–Rubin rifle, while the Mannlicher M1895 uses en-bloc clips. The Schmidt–Rubin series, which culminated in the K31, are also known for being among the most accurate military rifles ever made. Yet another variant of the straight-pull bolt action, of which the M1895 Lee Navy is an example, is a camming action in which pulling the bolt handle causes the bolt to rock, freeing a stud from the receiver and unlocking the bolt.

In 1993 the German Blaser company introduced the Blaser R93, a new straight-pull action where locking is achieved by a series of concentric "claws" that protrude/retract from the bolthead, a design that is referred to as Radialbundverschluss ("radial connection"). As of 2017 the Rifle Shooter magazine[9] listed its successor Blaser R8 as one of the three most popular straight pull rifles together with Merkel Helix[10] and Browning Maral.[11] Some other notable modern straight pull rifles are made by Chapuis,[12] Heym,[13] Lynx,[14] Rößler,[15] Strasser,[16] and Steel Action.[17]

Most straight pull rifles have a firing mechanism without a hammer, but there are some hammer fired models like for instance the Merkel Helix. Firearms using a hammer usually have a comparably longer lock time than hammer-less mechanisms.

In the sport of biathlon, because shooting speed is an important performance factor and semi-automatic guns are illegal for race use, straight-pull actions are quite common, and are used almost exclusively on the Biathlon World Cup. The first company to make the straight-pull action for .22 caliber was J. G. Anschütz; the action is specifically the straight pull ball bearing lock action, which features spring-loaded ball bearings on the side of the bolt which lock into a groove inside the bolt's housing. With the new design came a new dry-fire method; instead of the bolt being turned up slightly, the action is locked back to catch the firing pin.

Another distinct type of popular straight-pull design used in biathlon events is the "lateral toggle"-type straight-pull action, which used a hinged linkage to cycle the bolt. The advantage of such action design is that the same bolt movements can be achieved with significantly reduced range of movement by the user's hand. The two earliest companies who have made the lateral toggle are Finn biathlon, as well as Izhmash. Finn was the first to make this type of action, however, due to the large swing of the arm as well as the stiffness of the bolt, these rifles fell out of favour and have been discontinued. Izhmash improved on the lateral swing with their Biathlon 7-3 and 7-4 series rifles, which have some use on world cups, but are largely thought of as inaccurate as well as having the inconvenience of having to remove the shooter's hand from the grip. Currently, the Austrian company ISSC GmbH produces a toggle action for both their SPA biathlon rifle and the Steyr Scout RFR. The Idaho-based American firearm manufacturer Primary Weapons Systems also used to produce the T3 Summit rifle that featured a toggle-action design based on the Ruger 10/22 footprint, but has since discontinued the model. The Iowa-based company Volquartsen Custom, which is well known for making high-end custom firearms based on Ruger models, has since taken over the production of the PWS T3 Summit and re-introduced it as the Volquartsen Summit rifle.

Operating the bolt

Typically, the bolt consists of a tube of metal inside of which the firing mechanism is housed, and which has at the front or rear of the tube several metal knobs, or "lugs", which serve to lock the bolt in place. The operation can be done via a rotating bolt, a lever, cam-action, locking piece, or a number of systems. Straight-pull designs have seen a great deal of use, though manual turn-bolt designs are what is most commonly thought of in reference to a bolt-action design due to the type ubiquity. As a result, the bolt-action term is often reserved for more modern types of rotating bolt-designs when talking about a specific weapon's type of action. However, both straight-pull and rotating bolt rifles are types of bolt-action rifles. Lever-action and pump-action weapons must still operate the bolt, but they are usually grouped separately from bolt-actions that are operated by a handle directly attached to a rotating bolt. Early bolt-action designs, such as the Dreyse needle gun and the Mauser Model 1871, locked by dropping the bolt handle or bolt guide rib into a notch in the receiver, this method is still used in .22 rimfire rifles. The most common locking method is a rotating bolt with two lugs on the bolt head, which was used by the Lebel Model 1886 rifle, Model 1888 Commission Rifle, Mauser M 98, Mosin–Nagant and most bolt-action rifles. The Lee–Enfield has a lug and guide rib, which lock on the rear end of the bolt into the receiver.

Loading

Most bolt-action firearms are fed by an internal magazine loaded by hand, by en bloc, or stripper clips, though a number of designs have had a detachable magazine or independent magazine, or even no magazine at all, thus requiring that each round be independently loaded. Generally, the magazine capacity is limited to between two and ten rounds, as it can permit the magazine to be flush with the bottom of the rifle, reduce the weight, or prevent mud and dirt from entering. A number of bolt-actions have a tube magazine, such as along the length of the barrel. In weapons other than large rifles, such as pistols and cannons, there were some manually operated breech loading weapons. However, the Dreyse Needle fire rifle was the first breech-loader to use a rotating bolt design. Johann Nicholas von Dreyse's rifle of 1838 was accepted into service by Prussia in 1841, which was in turn developed into the Prussian Model 1849. The design was a single-shot breech loader, and had the now familiar arm sticking out from the side of the bolt, to turn and open the chamber. The entire reloading sequence was a more complex procedure than later designs, however, as the firing pin had to be independently primed and activated, and the lever was only used to move the bolt.

Benefits and drawbacks

Bolt-action firearms can theoretically achieve higher muzzle velocity and therefore have more accuracy than semi-automatic rifles because of the way the barrel is sealed. In a semi-automatic rifle, some of the energy from the charge is directed towards ejecting the spent shell and loading a new cartridge into the chamber. In a bolt action, the shooter performs this action by manually operating the bolt, allowing the chamber to be better sealed during firing, so that much more of the energy from the expanding gas can be directed forward. However, numerous other factors related to design and ammunition affect reliability and accuracy, and well designed modern semi-automatic rifles can be exceptionally accurate. Because of the combination of relatively light weight, reliability, high potential accuracy and lower cost, the bolt action is still the design of choice for many hunters, target shooters and marksmen.

The bolt action's locking lugs are normally at the front of the breech (some designs have additional "safety lugs" at the rear), and this increases potential accuracy relative to a design which locks the breech at the rear, such as a lever action. Also, a bolt action's only moving parts when firing are the pin and spring. Since it has fewer moving parts and a short lock time, it has less of a chance of being thrown off target and/or malfunctioning.

Because the spent cartridge is removed by manual action rather than automatically ejected, it can help a marksman remain hidden. Because the cartridge is not visibly flung into the air and onto the ground, a bolt action may be less likely to reveal a shooter's position. Also, the cartridge can be removed when most prudent, allowing the shooter to remain still until reloading is tactically feasible. Bolt actions are also easier to operate from a prone position than other manually repeating mechanisms and work well with box magazines, which are easier to fill and maintain than tubular magazines.

The integral strength of the design means very powerful magnum cartridges can be chambered without significantly increasing the size or weight of the weapon. For example, some of the most powerful elephant guns are in the same weight range (7–10 lbs.) as a typical deer rifle, while delivering several times the kinetic energy to the target. The recoil of these weapons, however, is correspondingly severe. By contrast, the operating mechanism of a semi-automatic weapon must increase in mass and weight as the cartridge it fires increases in power. This means that semi-automatic rifles firing magnum cartridges tend to be relatively heavy and impractical for many types of hunting.

The bolt action requires four distinct movements and is therefore generally slower than other major manual repeating mechanisms, such as lever and pump action, which generally require two movements, although straight-pull bolt actions also require only two distinct movements. In addition, the trigger hand must leave the gun and regrip the weapon after each shot, usually resulting in the shooter having to realign his sight and reacquire the target for every shot. It is also not ambidextrous, and left-handed models tend to be more expensive.

Safety and headspace

On used bolt-action firearms, especially, the headspace should be checked with headspace gauges prior to shooting to ensure it is correct, and to prevent over-stressing chambers and cartridge brass. Some bolt-action rifles, such as the Lee–Enfield, have a series of different standard length bolt heads for correctly fitting bolts rifles during final stages of mass manufacture. These may also extend the service life of a rifle for taking up excess slack between bolt face and chamber occurring from long years of service. In the case of the No. 4 Lee–Enfield bolt, the bolt heads themselves are replaceable separate from the bolt and are marked 0, 1, 2, or 3, with each bolt head in sequence being nominally 0.003" longer than the bolt head numbered one less, for easily taking up any action stretching that may have occurred. It is possible to replace such a bolt head without tools by disassembling the bolt from the action, unscrewing the bolt head, and replacing the bolt head with the next higher number bolt head, for restoring a safe headspace.

The interrelated mechanics of safe trigger function, correct headspace, and equal bearing of the locking lugs requires that the bolt and action assembly are factory "fitted". Usually shown by the rifle serial number, applied to both bolt and action, indicating they are a matched pair. Accidental or deliberate swapping of bolts between similar rifles is not unusual, but is potentially dangerous. Any rifle with mismatched action/bolt serial numbers should be considered to be unsafe to fire until checked and so marked by a competent gunsmith or armourer.

Furthermore, there are many subtle issues involving the provenance of a rifle and its ammunition. Many calibres have dual civilian/military uses but are not completely identical – e.g. the .308 Winchester/7.62mm NATO and .223 Remington/5.56mm NATO have very slight differences in chamber sizes. Military ammunition often has thicker brass, and harder primers. Over major wars there were literally millions of surplus rifles converted to civilian uses (sporterized); many may be unsafe with modern ammunition – caution is required with any ex-military bolt action.

See also

Some notable bolt action rifles

Other Firearm Actions

References

- ↑ Dupuy, Trevor N., Colonel, U.S. Army (rtd). Evolution of Weapons and Warfare (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1980), p. 293.

- ↑ http://www.nramuseum.org/guns/the-galleries/a-nation-asunder-1861-to-1865/case-15-union-muskets-and-rifles/greene-breechloading-underhammer-percussion-rifle.aspx

- ↑ Firearms Past and Present: Jaroslav Lugs, p. 147.

- ↑ http://rfi.gov.in/booking/prod/315_Sporting.htm

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GhABWdIx8bk

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spJQapFXEO8

- ↑ Swiss Straight-Pull First Impressions – Forgotten Weapons

- ↑ Break That Case: A Visceral Illustration of Primary Extraction, with Bloke on the Range - The Firearm BlogThe Firearm Blog

- ↑ Straight pull rifles - in depth analysis of three popular straight pulls | Detailed tests & reviews on the newsest rifles to hit the market | Rifle Shooter

- ↑ Merkel RX Helix Review | Sporting Rifle magazine

- ↑ Browning Maral | Straight-Pull Rifles Reviews | Gun Mart

- ↑ Chapuis Armes "ROLS": New Straight Pull Bolt Action Rifle - The Firearm BlogThe Firearm Blog

- ↑ Heym SR30 straight-pull rifle review review - Shooting UK

- ↑ Lynx 94 Review | Sporting Rifle magazine

- ↑ Titan 16 straight-pull rifle review - Shooting UK

- ↑ Strasser RS Solo review - Shooting UK

- ↑ German Straight Pull Bolt Action Rifles by Steel Action - The Firearm BlogThe Firearm Blog

Further reading

- Zwoll, Wayne (2003). Bolt Action Rifles. Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-87349-660-5.

External links

![]()