Black Museum

The Black Museum, or The Crime Museum of Scotland Yard, is a collection of criminal memorabilia kept at New Scotland Yard, headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service in London, England. The museum came into existence sometime in 1874, although unofficially. It was housed at Scotland Yard, and grew from the collection of prisoners' property gathered under the authority of the Prisoners' Property Act 1869. The act was intended to help the police in their study of crime and criminals. By 1875, it had become an official museum, although not open to the public, with a police inspector and a police constable assigned to official duty there.

History

The concept of the Black Museum was conceived in 1874 by a serving Inspector, who at that time had collected together a number of items, with the intention of giving police officers practical instruction on how to detect and prevent crime. Prior to an Act of 1869, items used in the commission of a crime were retained by police until their owners had reclaimed them, but this 1869 Act gave authority for police to either destroy these items, or retain them for instructional purposes.[1] By the latter part of 1874, official authority was given for a crime museum to be opened.[2]

The founding Inspector Neame,[3] with the help of a P.C. Randall, gathered together sufficient material of both old and new cases—initially pertaining to exhibits found in the possession of burglars and thieves—to enable a museum to be subsequently opened. The actual date in 1875 when the Black Museum opened is not known, but the permanent appointment of Neame and Randall to duty in the Prisoners Property Store on 12 April suggests that the museum may have come into being in the latter part of that year.[4]

There was no official opening of the museum, and two years elapsed before a record of the first visitors was recorded. This was on 6 October 1877 when the Commissioner, Sir Edmund Henderson, KCB, accompanied by the Assistant Commissioners, Lt. Col. Labolmondiere and Capt. Harris, visited with other dignitaries. By now there was a steady increase in the number viewing the displays and the first visitors book, which spans some eighteen years from 1877 to 1894, reads like a current 'Who's Who'. Certainly not all visitors were asked to sign the visitors book but, as instruction in the museum was part of CID training, the museum was in constant use.

In 1877 the name 'Black Museum' was coined, when on 8 April a reporter from The Observer newspaper used the term after being refused a visit by Inspector Neame. However the museum is now referred to as the Crime Museum.

In 1890 the museum moved with the Metropolitan Police Office to new premises at the other end of Whitehall,[5] on the newly constructed Thames Embankment. The building, constructed by Norman Shaw RA, and made of granite quarried by convicts on Dartmoor, was called New Scotland Yard. A set of rooms in the basement housed the museum and, although there was no Curator as such, PC Randall was responsible for keeping the place tidy, adding to exhibits, vetting applications for visits and arranging dates for them. The museum was closed during both World War I and II, and in 1967, with the move of the Metropolitan Police Headquarters to new premises in Victoria Street, S.W.1, the museum was housed in rooms on the second floor.

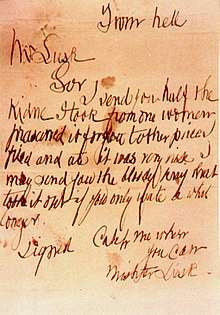

The Museum was then moved to New Scotland Yard in the 1980s and was subject to substantial renovation in recent years. The Crime Museum, as it is now called, currently resides in Room 101 at New Scotland Yard and consists of two sections. The first, a replica of the original museum, contains a substantial collection of melee weapons, some overt, some concealed all of which have been used in murders or serious assaults in London, these include shotguns disguised as umbrellas and numerous walking stick swords. The room also contains a selection of hangman's nooses, including that used to perform the UK's last-ever execution and death masks made for executed criminals. There are also displays from famous cases which include Charlie Peace and letters allegedly written by Jack the Ripper.

The newer section of the museum contains many exhibits from 20th-century crimes, notably the fake De Beers diamond from the Millennium Dome heist and Dennis Nilsen's actual stove. The second room contains cabinets under the following categories Famous Murders, Notorious Poisoners, Murder of Police Officers, Royalty, Bank Robberies, Espionage, Sieges and Hostages and hijacking with real exhibits and details. On display is even the ricin-filled pellet that killed Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov in 1978. Also on display is a model of the possible umbrella that fired the pellet.

The museum can be visited by police officers from any of the country's police forces by prior appointment, though not without difficulty due to its popularity. The Black Museum of criminal artefacts also hosts more than 500 items preserved at a constant temperature of sixty-two degrees Fahrenheit. A special place is reserved for a set of printing plates, a remarkable series of forged banknotes, and a cunningly hollowed-out kitchen door once used to conceal them. These items formerly belonged to Charles Black, the most prolific counterfeiter in the Western Hemisphere.

In 1951 British commercial radio producer Harry Alan Towers produced a radio series hosted by Orson Welles called The Black Museum, inspired by the catalogue of items on display. Each week, the programme featured an item from the museum and a dramatization of the story surrounding the object to the macabre delight of audiences. Often mistakenly cited as a BBC production, Towers commercially syndicated the programme throughout the English-speaking world. The American radio writer Wyllis Cooper also wrote and directed a similar anthology for NBC that ran at the same time in the U. S. called Whitehall 1212, for the telephone number of Scotland Yard, the program debuted on 18 November 1951, and was hosted by Chief Superintendent John Davidson, curator of the Black Museum.

A major exhibition of artifacts from the museum, The Crime Museum Uncovered, was held at the Museum of London 9 October 2015 – 10 April 2016.[6] This was the first, and supposedly last, time that the public were granted access to the exhibits.

Some featured cases on exhibit

Udham Singh

Udham Singh was an Indian revolutionary who shot and killed Michael O'Dwyer, the former Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab in British India

Ruth Ellis

Ruth Ellis was the last woman to be executed in the United Kingdom, after being convicted of the murder of her lover, David Blakely.

John Reginald Halliday Christie

John Reginald Halliday Christie was a notorious English serial killer active in the 1940s and early 1950s[7]

The Stratton Brothers

Stratton Brothers case refers to the Stratton Brothers who were the first men to be convicted in Great Britain for murder based on fingerprint evidence[8]

John George Haigh

John George Haigh was an English serial killer, active between 1944 and 1949[9]

Neville Heath

Neville Heath, an English killer who was responsible for the murders of at least two young women who was executed in London in 1946

Dennis Nilsen

Dennis Nilsen, a serial killer and necrophiliac, also known as the Muswell Hill Murderer and the Kindly Killer, who committed the murders of 15 young men in London, England

Dr. Neill Cream

Thomas Neill Cream, also known as the Lambeth Poisoner, was a Scottish-born serial killer[10]

PC Keith Blakelock

The overalls of P.C. Keith Blakelock, who was stabbed to death in the Broadwater Farm housing estate are kept in the Black Museum. Several people have been charged with his murder but acquitted. The Met continues to pursue others involved in his murder[11]

In other media

- There is a fictional Black Museum, inspired by the actual one, inside the Grand Hall of Justice in the Judge Dredd comic strip.

- A fictional version of The Black Museum is often referred to in the Dylan Dog comic series and, in some stories, exhibits are stolen from the museum.

- In the 1944 film The Lodger, Inspector Warwick (George Sanders) gives a tour of the museum to Kitty Langley (Merle Oberon).

- A 1958 horror film called Horrors of the Black Museum references the Black Museum in a story of a crime writer (played by Michael Gough) who commits grisly murders in order to write articles and books about them for public consumption.

- The fourth series of Charlie Brooker's Black Mirror has an episode called "Black Museum".

- Tony Parsons wrote about the Black Museum in his books about detective Max Wolfe.

Other uses

The term was also applied to a museum of failed engineering components collected by David Kirkaldy at his testing works at 99 Southwark Street, Southwark, London. This museum was destroyed in the London Blitz. The artefacts included fractured lugs from the Tay Bridge disaster.

References

- ↑ Waddell 1993, p. 4.

- ↑ Waddell 1993, pp. 5-7.

- ↑ Schulz, Dorothy Moses M.; Haberfeld, Dr. Maria (Maki) R.; Sullivan, Larry E.; Rosen, Marie Simonetti (2005). Encyclopedia of Law Enforcement. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 348.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ The Black Museum ISBN 978-0-316-90332-5 pp. 5-6

- ↑ The Murders of the Black Museum ISBN 978-1-85471160-1 p. 13

- ↑ Scotland Yard's Crime Museum Opens to Public for First Time in 140 Years NBC News, 22 November 2015.

- ↑ The Black Museum ISBN 978-0-316-90332-5 p. 171

- ↑ The Black Museum ISBN 978-0-316-90332-5 p. 171

- ↑ The Black Museum ISBN 978-0-316-90332-5 p. 161

- ↑ The Black Museum ISBN 978-0-316-90332-5 p. 84

- ↑ "DNA test for Blakelock's uniform", BBC News, 3 October 2004.

Cited works and further reading

- Honeycombe, Gordon (1982). The Murders of the Black Museum: 1870:1970. Bloomsbury Books. ISBN 978-1-85471160-1.

- Ohmart, Ben (2002). It's That Time Again. Albany & Bear Manor Media. ISBN 0-9714570-2-6.

- Waddell, Bill (1993). The Black Museum: New Scotland Yard. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-90332-5.