From Hell letter

| Jack the Ripper letters |

|---|

The "From Hell" letter (also called the "Lusk letter")[1][2] is a letter that was posted in 1888, along with half a human kidney, by a person who claimed to be the serial killer known as Jack the Ripper. The murderer killed and mutilated at least five female victims in the Whitechapel area of London over a period of several months, the case attracting a great deal of attention both at the time and since. The exact number of victims has never been conclusively proven, and the identity of the perpetrator of the Whitechapel killings has likewise remained unsolved.[2]

Postmarked on 15 October 1888, the letter was received by George Lusk, the chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, the following day. The message was accompanied by a preserved section of a human kidney; the letter's writer claimed to have eaten the other half of the organ. The police received a large number of letters claiming to be from the murderer, at one point having to deal with an estimated 1,000 letters related to the case, but the "From Hell" message is one of the few that has received serious attention as possibly being genuine. Opinions on the matter have remained divided.[2] Several fictional works have referred to the Lusk letter, an example being the thriller novel Dust and Shadow.[3]

Letter

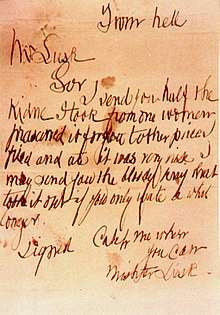

The text of the letter reads:[4]

From hell.

Mr Lusk,

Sor

I send you half the Kidne I took from one woman prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer

signed

Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk

The original letter, as well as the kidney that accompanied it, have subsequently been lost along with other items that were originally contained within the Ripper police files. The image shown here is from a photograph taken before the loss.[4]

Background

The news media reacted with alarm at the fact that a multiple murderer was on the loose; the 31 August 1888 death of Mary Ann Nichols resulted in numerous articles about the individual known as "Leather Apron" or "the Whitechapel murderer". The grotesque mutilation of Nichols and later victims were generally described as involving their bodies "ripped up" and residents spoke of their worries of a "ripper" or "high rip" gang. However, the identification of the killer as "Jack" the Ripper did not take place until after 27 September, when the offices of Central News Ltd received the "Dear Boss" letter. The message's writer listed Jack the Ripper as his "trade name" and vowed to continue killing until arrested, also threatening to send the ears of his next victim to the police.[5]

While the newsmen considered the letter a mere joke, they decided after two days to notify Scotland Yard of the matter. The double murder of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes took place the night that the police received the "Dear Boss" letter. The Central News people received a second communication known as the "Saucy Jacky" postcard on 1 October 1888, the day after the double murder, and the message was duly passed over to the authorities. Copies of both messages were soon posted to the public in the hopes that the writing style would be recognised. While the police felt determined to discover the author of both messages, they found themselves overwhelmed by the media circus around the Ripper killings and soon received a large amount of material, most of it useless.[5]

Analysis

Though hundreds of letters claiming to be from the killer were posted at the time of the Ripper murders, many researchers argue that the "From Hell" letter is one of a handful of possibly authentic writings received from the murderer.[5] Its author did not sign it with the "Jack the Ripper" pseudonym, distinguishing it from the earlier "Dear Boss" and "Saucy Jacky" messages as well as their many imitators. The handwriting of the earlier two messages mentioned are also similar to each other while being dissimilar to the one made "From Hell".[6] The letter's specific delivery to Lusk personally, without reference made to either the police or the British government generally, could indicate a personal animosity of the writer towards either Lusk as an individual or to the local Whitechapel community establishment (of which Lusk was a member).[7]

The "From Hell" letter is noticeably written at a much lower literacy level than the other two, featuring several errors in spelling and grammar. Scholars have debated whether this is a deliberate misdirection, as the author observed the silent k in 'knif' and h in 'while'. The formatting of the letter also features a cramped writing style in which letters are pressed together haphazardly; many ink blots appear in a manner that may indicate that the writer was unfamiliar with using a pen.[5] The formatting of the message may point to it being a hoax by an otherwise well-educated individual, but some researchers have argued that it is the genuine work of a partly functional but deranged individual.[6][7]

Opinions of those that have looked into the case are divided. The possibility has been raised that all of the communications supposedly from the Whitechapel murderer are fraudulent, acts done by cranks or by journalists seeking to increase the media frenzy even more. Scotland Yard had reason to doubt the validity of the latter yet ultimately did not take action against suspected reporters.[2][5] However, the many differences between the "From Hell" letter and vast majority of the messages received has been cited by some figures analysing the case, such as a forensic handwriting expert interviewed by the History Channel and another interviewed by the Discovery Channel, as evidence to view it as maybe the only authentic letter.[6][7]

The primary reason this letter stands out more than any other is that it was delivered with a small box containing half of what doctors later determined was a human kidney, preserved in spirits. One of murder victim Catherine Eddowes' kidneys had been removed by the killer. Medical opinion at the time was that the organ could have been acquired by medical students and sent with the letter as part of a hoax.[2][5] Lusk himself believed that this was the case and did not report the letter until he was urged to do so by friends.[8]

Arguments in favour as to the letter's genuineness sometimes state that contemporary analysis of the kidney by Dr. Thomas Openshaw of the London Hospital found that it came from a sickly alcoholic woman who had died within the past three weeks, evidence that it belonged to Eddowes. However, these facts have been in dispute as contemporary media reporting at the time as well as later recollections give contradictory information about Openshaw's opinions. Historian Philip Sugden has written that perhaps all that can be concluded given the uncertainty is that the kidney was human and from the left side of the body.[2][5]

A contemporary police lead found that shopkeeper Emily Marsh had encountered a visitor at her shop, located in London's Mile End Road, with an odd, unsettling manner in both his appearance and speech. The visitor asked Marsh for the address of Mr. Lusk, which he wrote in a personal notebook, before abruptly leaving. He was described as a slim man wearing a long black overcoat at about six feet in height that spoke with an Irish accent, his face featuring a dark beard and mustache. While the event took place the day before Lusk received the "From Hell" message and occurred in the area in which it is considered to have been postmarked, the fact that Lusk received so many hoax letters during this time means that the suspicious individual may have been another crank.[5]

Forensic handwriting expert Michelle Dresbold, working for the History Channel documentary series MysteryQuest, has argued that the letter is genuine based on the peculiar characteristics of the handwriting, particularly the "invasive loop" letter "y"s. The criminal profiling experts in the program also created a profile of the killer, stating that he possessed a deranged animosity towards women and skills at using a knife. Based on linguistic clues (including the use of the particular spelling of the word "prasarved" (preserved), Dresbold felt that the letter showed strong evidence that the writer was Irish or of Irish extraction, linking the letter to Ripper suspect Francis Tumblety. Tumblety was an itinerant Irish-American quack doctor who was mentally ill and who had resided in London during the year of the murders. He had multiple encounters with the law and a strong dislike of women, as well as a background collecting body parts. However, after arresting him at the time as a suspect, the police ended up releasing him on bail, having failed to find hard evidence against him. He ultimately died of a heart condition in the U.S. in 1903.[6] Sugden has also written that the author may have had an Irish background but also stated that he may have had Cockney mannerisms.[5]

The purported diary of James Maybrick, another man who has been proposed as a Ripper suspect, contains references to the "From Hell" letter, particularly the alleged cannibalism. However, even if the diary is assumed to be genuine, the handwriting does not match that of the letter at all.[2] A Kirkus Reviews article has referred to the diary rumor as a "hoax" that is one of several "bizarre hypotheses" relating to the case.[9]

Later references and legacy

Regarded as the first internationally publicised set of serial killings, with the perpetrator never conclusively identified, the matter has attracted much attention for decades,[6] with fictional works referring specifically to the Lusk letter. The graphic novel From Hell about the Ripper murders takes its name from the letter. Created by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell, the work was originally published in serial form from 1989 to 1996, and first collected as a single piece in 1999. Adapted into a 2001 feature film starring Johnny Depp and Heather Graham, the comic series features the actual killer as a main protagonist, going into his tortured mind and warped justifications for the murders. Cultural commentators such as Professor Elizabeth Ho have highlighted the way in which the work comments "on the present's relationship to the past", with "text and image" placed "in critical tension". From Hell is commonly held to be one of the best graphic novels ever created.[10][11]

Lyndsay Faye's thriller novel Dust and Shadow: An Account of the Ripper Killings by Dr. John H. Watson, a Sherlock Holmes pastiche, pits the famous detective against the Whitechapel murderer. Holmes' colleague, Dr. Watson, comes upon the "From Hell" letter and reacts with horror, remarking: "What sort of frenzied imagination could be capable of constructing such trash?" He sees it as an authentic and a helpful clue, while being unsure about how to proceed. Holmes expresses his deep anger at "the villain" for being able to elude him for so many days, vowing to soldier on.[3]

The mobile video game Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell was released in 2010 by Anuman. The gameplay is based around a hunt for hidden objects. The player takes the role of a sensationalist reporter willing to make up details about the murders and even compose hoax messages himself. The protagonist often confronts the London police and attracts considerable suspicion as he keeps popping up where the Ripper had been seen.[12]

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- From Hell, a graphic novel that takes its title from the "From Hell" letter

- From Hell, a film loosely based on the graphic novel

- Jack the Ripper suspects

- Offender profiling

- Whitechapel Vigilance Committee

References

- ↑ Grove, Sophie (June 9, 2008). "You Don't Know Jack: A new museum exhibition opens the case file on Jack the Ripper—and affords a grim look at the London of the time—a city made for murder". Newsweek. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jones, Christopher (2008). The Maybrick A to Z. Countyvise Ltd. Publishers. pp. 162–165. ISBN 9781906823009.

- 1 2 Faye, Lyndsay (April 2009). Dust and Shadow: An Account of the Ripper Killings by Dr. John H. Watson. Simon & Schuster. pp. 193–201. ISBN 9781416583622.

- 1 2 Jack the Ripper article on the Ripper letters. Casebook.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sugden, Philip (March 2012). "Chapter 13: Letters From Hell". The Complete History of Jack the Ripper. Little Brown. ISBN 9781780337098.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Jack the Ripper". MysteryQuest. Season 1. Episode 8. November 11, 2009. History Channel.

- 1 2 3 "Jack the Ripper". Unearthing Ancient Secrets. Season 1. Episode 7. March 2, 2009. Discovery Channel.

- ↑ Douglas, John; Mark Olshaker (2001). The Cases That Haunt Us. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-7432-1239-7.

- ↑ "The Complete History of Jack the Ripper". Kirkus Reviews. May 20, 2010. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (November 17, 2014). "'From Hell' Drama Based On Jack The Ripper Graphic Novel In Works At FX". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ↑ Ho, Elizabeth (April 2012). "Chapter 1: Neo-Victorianism and "Ripperature" – Alan Moore's From Hell". Neo-Victorianism and the Memory of Empire. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781441197788.

- ↑ Bell, Erin (January 28, 2010). "Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell Review". Gamezebo.com. Retrieved September 11, 2015.