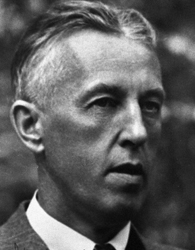

Bill W.

| Bill W. | |

|---|---|

Bill Wilson, Alcoholics Anonymous | |

| Born |

William Griffith Wilson November 26, 1895 East Dorset, Vermont |

| Died |

January 24, 1971 (aged 75) Miami, Florida |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Website |

steppingstones |

William Griffith Wilson (November 26, 1895 – January 24, 1971), also known as Bill Wilson or Bill W., was the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).

AA is an international mutual aid fellowship with about 20 million members worldwide belonging to approximately 10,000 groups, associations, organizations, cooperatives, and fellowships of alcoholics helping other alcoholics achieve and maintain sobriety.[1] Following AA's Twelfth Tradition of anonymity, Wilson is commonly known as "Bill W." or "Bill." In order to communicate among one another, members of "AA" will often ask those who appear to be suffering or having a relapse from alcoholism if they are "friends with Bill". Although this question can be confusing, because "Bill" is a common name, it does provide a means of establishing a rapport with those who are familiar with the saying and in need of help. After Wilson's death in 1971, and amidst much controversy within the fellowship, his full name was included in obituaries by journalists who were unaware of the significance for maintaining anonymity within the organization.[2]

Wilson's sobriety from alcohol, which he maintained until his passing, began December 11, 1934. In 1955 Wilson turned over control of AA to a board of trustees. Wilson died of emphysema complicated by pneumonia in 1971. In 1999 Time listed him as "Bill W.: The Healer" in the Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century.[3]

Early life

Wilson was born on November 26, 1895, in East Dorset, Vermont, the son of Emily (née Griffith) and Gilman Barrows Wilson.[4] He was born at his parents' home and business, the Mount Aeolus Inn and Tavern. His paternal grandfather, William C. Wilson, was also an alcoholic. William C. Wilson decided to stop drinking alcohol immediately after having a "religious experience" when he was under the influence of psilocybin [nb 1] (/ˌsaɪləˈsaɪbɪn/ sy-lə-SY-bin) during a "soul searching" hike on Mount Aeolus.[6] His grandson, Bill, also felt a very strong desire to stop drinking shortly after sharing a similar experience.

Both of Bill's parents abandoned him soon after he and his sister were born—his father never returned from a purported business trip, and his mother left Vermont to study osteopathic medicine. Bill and his sister were raised by their maternal grandparents, Fayette and Ella Griffith. As a teen, Bill showed little interest in his academic studies and was rebellious. During a summer break in high school, he spent months designing and carving a boomerang to throw at birds, raccoons, and other local wildlife. After many difficult years during his early-mid teens, Bill became the captain of his high school's football team, and the principal violinist in its orchestra.[7] Bill also dealt with a serious bout of depression at the age of seventeen, following the death of his first love, Bertha Bamford, who died of complications from surgery.[8]

Marriage, work, and alcoholism

Wilson met his wife Lois Burnham during the summer of 1913, while sailing on Vermont's Emerald Lake; two years later the couple became engaged. He entered Norwich University, but depression and panic attacks forced him to leave during his second semester. The next year he returned, but was soon suspended with a group of students involved in a hazing incident.[9] Because no one would take responsibility, and no one would identify the perpetrators, the entire class was punished.[10]

The June 1916 incursion into the U.S. by Pancho Villa resulted in Wilson's class being mobilized as part of the Vermont National Guard and he was reinstated to serve. The following year he was commissioned as an artillery officer. During military training in Massachusetts, the young officers were often invited to dinner by the locals, and Wilson had his first drink, a glass of beer, to little effect.[11] A few weeks later at another dinner party, Wilson drank some Bronx cocktails, and felt at ease with the guests and liberated from his awkward shyness; "I had found the elixir of life," he wrote.[12] "Even that first evening I got thoroughly drunk, and within the next time or two I passed out completely. But as everyone drank hard, not too much was made of that."[13]

Wilson married Lois on January 24, 1918, just before he left to serve in World War I as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Coast Artillery.[14] After his military service, Wilson returned to live with his wife in New York. He failed to graduate from law school because he was too drunk to pick up his diploma.[15] Wilson became a stock speculator and had success traveling the country with his wife, evaluating companies for potential investors. (During these trips Lois had a hidden agenda: she hoped the travel would keep Wilson from drinking.[16]) However, Wilson's constant drinking made business impossible and ruined his reputation.

In 1933 Wilson was committed to the Charles B. Towns Hospital for Drug and Alcohol Addictions in New York City four times under the care of Dr. William D. Silkworth. Silkworth's theory was that alcoholism was a matter of both physical and mental control: a craving, the manifestation of a physical allergy (the physical inability to stop drinking once started) and an obsession of the mind (to take the first drink).[17] Wilson gained hope from Silkworth's assertion that alcoholism was a medical condition, but even that knowledge could not help him. He was eventually told that he would either die from his alcoholism or have to be locked up permanently due to Wernicke encephalopathy (commonly referred to as "wet brain").

A spiritual program for recovery

In November 1934, Wilson was visited by old drinking companion Ebby Thacher. Wilson was astounded to find that Thacher had been sober for several weeks under the guidance of the evangelical Christian Oxford Group.[18] Wilson took some interest in the group, but shortly after Thacher's visit, he was again admitted to Towns Hospital to recover from a bout of drinking. This was his fourth and last stay at Towns hospital under Doctor Silkworth's care and he showed signs of delirium tremens.[19] It was while undergoing treatment with The Belladonna Cure that Wilson experienced his "Hot Flash" spiritual conversion and quit drinking.[20] Earlier that evening, Thacher had visited and tried to persuade him to turn himself over to the care of a Christian deity who would liberate him from alcohol.[21] According to Wilson, while lying in bed depressed and despairing, he cried out, "I'll do anything! Anything at all! If there be a God, let Him show Himself!"[22] He then had the sensation of a bright light, a feeling of ecstasy, and a new serenity. He never drank again for the remainder of his life. Wilson described his experience to Dr. Silkworth, who told him, "Something has happened to you I don't understand. But you had better hang on to it".[23]

Wilson joined the Oxford Group and tried to help other alcoholics, but succeeded only in keeping sober himself. During a failed business trip to Akron, Ohio, Wilson was tempted to drink again and decided that to remain sober he needed to help another alcoholic. He called phone numbers in a church directory and eventually secured an introduction to Dr. Bob Smith, an alcoholic Oxford Group member. Wilson explained Doctor Silkworth's theory that alcoholics suffer from a physical allergy and a mental obsession. Wilson shared that the only way he was able to stay sober was through having had a spiritual experience. Smith was familiar with the tenets of the Oxford Group and upon hearing Wilson's experience, "began to pursue the spiritual remedy for his malady with a willingness that he had never before been able to muster. After a brief relapse, he sobered, never to drink again up to the moment of his death in 1950".[24] Wilson and Smith began working with other alcoholics. After that summer in Akron, Wilson returned to New York where he began having success helping alcoholics in what they called "a nameless squad of drunks" in an Oxford Group there.

In 1938, after about 100 alcoholics in Akron and New York had become sober, the fellowship decided to promote its program of recovery through the publication of a book, for which Wilson was chosen as primary author. The book was given the title Alcoholics Anonymous and included the list of suggested activities for spiritual growth known as the Twelve Steps. The movement itself took on the name of the book. Later Wilson also wrote the Twelve Traditions, a set of spiritual guidelines to ensure the survival of individual AA groups. The AA general service conference of 1955 was a landmark event for Wilson in which he turned over the leadership of the maturing organization to an elected board.

Political beliefs

Wilson strongly advocated that AA groups have not the "slightest reform of political complexion".[25] In 1946, he wrote "No AA group or members should ever, in such a way as to implicate AA, express any opinion on outside controversial issues -- particularly those of politics, alcohol reform or sectarian religion. The Alcoholics Anonymous groups oppose no one. Concerning such matters they can express no views whatever. " Reworded, this became "Tradition 10" for AA.[26][27]

The final years

During the last years of his life, Wilson rarely attended AA meetings to avoid being asked to speak as the co-founder rather than as an alcoholic.[28] A heavy smoker, Wilson eventually suffered from emphysema and later pneumonia. He continued to smoke while dependent on an oxygen tank in the late 1960s.[29] He drank no alcohol for the final 37 years of his life; however, in the last days of his life he made demands for whiskey and became belligerent when refused.[29] During this period, Wilson was visited by colleagues and friends who wanted to say goodbye. Wilson died of emphysema and pneumonia on January 24, 1971, en route to treatment in Miami, Florida. He is buried in East Dorset, Vermont.[30]

Temptation and reports of infidelity

Though Wilson alluded to unfulfilled temptation in an account in the Alcoholics Anonymous "Big Book" ("There had been no real infidelity," he wrote, "for loyalty to my wife, helped at times by extreme drunkenness, kept me out of those scrapes."[31]), biographers Francis Hartigan, Matthew Raphael, and Susan Cheever cite claims that Wilson had sexual contacts outside of his marriage.

Francis Hartigan, AA biographer and personal secretary to Lois Wilson, in his book states that in the mid 1950s Bill began an affair with Helen Wynn, a woman 22 years his junior. Bill at one point discussed divorcing Lois to marry Helen. Bill eventually overcame the AA trustees' objections, and renegotiated his royalty agreements with them in 1963, which allowed him to include Helen Wynn in his estate. He left 10 percent of his book royalties to her and the other 90 percent to his wife Lois. In 1968, with Bill's illness making it harder for them to spend time together, Helen bought a house in Ireland.[32]

Personal letters between Wilson and his wife Lois spanning a period of more than 60 years can be found in the archives at Stepping Stones, their former home in Katonah, New York, and in AA's General Service Office archives in New York.[33]

Alternative cures and spiritualism

In the 1950s Wilson used LSD in medically supervised experiments with Betty Eisner, Gerald Heard, and Aldous Huxley. With Wilson's invitation, his wife Lois, his spiritual adviser Father Ed Dowling, and Nell Wing also participated in experimentation of this drug. Later Wilson wrote to Carl Jung, praising the results and recommending it as validation of Jung's spiritual experience. (The letter was not in fact sent as Jung had died.)[34] According to Wilson, the session allowed him to re-experience a spontaneous spiritual experience he had had years before, which had enabled him to overcome his own alcoholism.

Bill was enthusiastic about his experience; he felt it helped him eliminate many barriers erected by the self, or ego, that stand in the way of one's direct experience of the cosmos and of God. He thought he might have found something that could make a big difference to the lives of many who still suffered. Bill is quoted as saying: "It is a generally acknowledged fact in spiritual development that ego reduction makes the influx of God's grace possible. If, therefore, under LSD we can have a temporary reduction, so that we can better see what we are and where we are going — well, that might be of some help. The goal might become clearer. So I consider LSD to be of some value to some people, and practically no damage to anyone. It will never take the place of any of the existing means by which we can reduce the ego, and keep it reduced."[35] Wilson felt that regular usage of LSD in a carefully controlled, structured setting would be beneficial for many recovering alcoholics. However, he felt this method only should be attempted by individuals with well-developed super-egos.[36]

In 1957 Wilson wrote a letter to Heard saying: "I am certain that the LSD experiment has helped me very much. I find myself with a heightened colour perception and an appreciation of beauty almost destroyed by my years of depressions." Most AAs were strongly opposed to his experimenting with a mind-altering substance.[37]

Wilson met Abram Hoffer and learned about the potential mood-stabilizing effects of niacin.[38] Wilson was impressed with experiments indicating that alcoholics who were given niacin had a better sobriety rate, and he began to see niacin "as completing the third leg in the stool, the physical to complement the spiritual and emotional." Wilson also believed that niacin had given him relief from depression, and he promoted the vitamin within the AA community and with the National Institute of Mental Health as a treatment for schizophrenia. However, Wilson created a major furor in AA because he used the AA office and letterhead in his promotion.[39]

For Wilson, spiritualism was a lifelong interest. One of his letters to adviser Father Dowling suggests that while Wilson was working on his book Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions, he felt that spirits were helping him, in particular a 15th-century monk named Boniface.[40] Despite his conviction that he had evidence for the reality of the spirit world, Wilson chose not to share this with AA. However, his practices still created controversy within the AA membership. Wilson and his wife continued with their unusual practices in spite of the misgivings of many AA members. In their house they had a "spook room" where they would invite guests to participate in seances using a Ouija board.[41][42]

Legacy

Alcoholics Anonymous has over 100,000 registered local groups and over 2 million active members worldwide.[43]

Wilson has often been described as having loved being the center of attention, but after the AA principle of anonymity had become established, he refused an honorary degree from Yale University and refused to allow his picture, even from the back, on the cover of Time. Wilson's persistence, his ability to take and use good ideas, and his entrepreneurial flair[44] are revealed in his pioneering escape from an alcoholic "death sentence," his central role in the development of a program of spiritual growth, and his leadership in creating and building AA, "an independent, entrepreneurial, maddeningly democratic, non-profit organization."[45]

Wilson is perhaps best known as a synthesizer of ideas,[46] the man who pulled together various threads of psychology, theology, and democracy into a workable and life-saving system. Aldous Huxley called him "the greatest social architect of our century,"[47] and Time magazine named Wilson to their Time 100 List of The Most Important People of the 20th Century.[48] Wilson's self-description was a man who, "because of his bitter experience, discovered, slowly and through a conversion experience, a system of behavior and a series of actions that work for alcoholics who want to stop drinking."

Biographer Susan Cheever wrote in My Name Is Bill, "Bill Wilson never held himself up as a model: he only hoped to help other people by sharing his own experience, strength and hope. He insisted again and again that he was just an ordinary man".

Wilson bought a house that he and Lois called Stepping Stones on an 8-acre (3 ha) estate in Bedford Hills, New York, in 1941, and he lived there with Lois until he died in 1971. After Lois died in 1988, the house was opened for tours and is now on the National Register of Historic Places;[49] it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2012.[50]

In popular culture

Over the years, Bill W., the formation of AA and also his wife Lois have been the subject of numerous projects, starting with My Name Is Bill W., a 1989 CBS Hallmark Hall of Fame TV movie starring James Woods as Bill W. and James Garner as Dr. Bob. Woods won an Emmy for his portrayal of Wilson. He was also depicted in a 2010 TV movie based on Lois' life, When Love Is Not Enough: The Lois Wilson Story, adapted from a 2005 book of the same name written by William G. Borchert. The film starred Winona Ryder as Lois Wilson and Barry Pepper as Bill W.[51]

A 2012 documentary, Bill W., was directed by Dan Carracino and Kevin Hanlon.[52]

The band Dream Theater dedicated each song of their Twelve-step Suite to Bill W.

In season five, episode one, of The Sopranos, Chris Moltisanti is seen reading My Search for Bill W.

Season 3 of Mystery Science Theater 3000 included Bill W. in the "Special Thanks" section of the end credits.

The band El Ten Eleven's song "Thanks Bill" is dedicated to Bill W. since lead singer Kristian Dunn's wife got sober due to AA. He states "If she hadn't gotten sober we probably wouldn't be together, so that's my thank you to Bill Wilson who invented AA". [53]

In Michael Graubart's Sober Songs Vol. 1, the song "Hey, Hey, AA" references Bill's encounter with Ebby Thatcher which started him on the path to recovery and eventually the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous. The lyric reads, "Ebby T. comes strolling in. Bill says, 'Fine, you're a friend of mine. Don't mind if I drink my gin.'" [54]

See also

- Addiction

- Jim Burwell

- History of Alcoholics Anonymous

- Lucille Kahn

- Rowland Hazard III ("Rowland H")

- Twelve-step program

- Bill W. and Dr. Bob (theatrical play)

- Bob Smith (Dr. Bob), the other co-founder of AA

Notes

- ↑ Synonyms and alternate spellings include: 4-PO-DMT (PO: phosphate; DMT: dimethyltryptamine), psilocybine, psilocibin, psilocybinum, psilotsibin, psilocin phosphate ester, and indocybin.[5]

Footnotes

- ↑ "Alcoholics Anonymous" p XIX

- ↑ John, Stevens. "Bill W. of Alcoholics Anonymous Dies". New York Times. The New Youk Times Company. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ↑ Heroes & Icons of the 20th Century. Time Magazine 153:(23) June 14, 1999. Retrieved 2012-07-20.

- ↑ "Ancestry of "Bill W."". Wargs.com. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- ↑ "Psilocybine – Compound Summary". PubChem. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ↑ Cheever, p 25.

- ↑ "Pass It ON" pp. 32-34

- ↑ B., Mel (2000). My Search For Bill W. pp. 5–10. ISBN 1-56838-374-6.

- ↑ Thomsen, Robert (1975). Bill W. pp. 75, 96. ISBN 0-06-014267-7.

- ↑ Raphael, p. 40.

- ↑ Cheever, p 73.

- ↑ "Bill W.: from the rubble of a wasted life, he overcame alcoholism and founded the 12-step program that has helped millions of others do the same." (Time's "The Most Important People of the 20th Century".) Susan Cheever. Time 153.23 (June 14, 1999): p201+.

- ↑ Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. (1984), "Pass it on": the story of Bill Wilson and how the A.A. message reached the world, ISBN 0-916856-12-7.

- ↑ Pass It On p 54.

- ↑ Cheever, 2004, p 91.

- ↑ Pass it on p 59.

- ↑ "Alcoholics Anonymous" p XXIII-XXVI

- ↑ Pass it on p 130.

- ↑ Alcoholics Anonymous "The Big Book" 4th edition p.13

- ↑ Pittman, Bill "AA the Way it Began p. 163-165

- ↑ An Alcoholic’s Savior: God, Belladonna or Both? New York Times, April 19, 2010.

- ↑ Pass it on p 121.

- ↑ Alcoholics Anonymous pg 14

- ↑ Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous p xvi

- ↑ Wilson, Bill. "The A.A. Service Manual Combined with Twelve Concepts for World Services" (PDF). Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ↑ "AA History - The 12 Traditions, AA Grapevine April, 1946". Barefootsworld.net. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- ↑ http://www.aa.org/en_pdfs/smf-122_en.pdf

- ↑ Raphael 2000, p. 167.

- 1 2 Cheever, 2004, pp 245 - 247.

- ↑ "William G. "Bill" Wilson". Find a Grave. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ Alcoholics Anonymous World Services 1936, Alcoholics Anonymous 3rd Edition, page 3

- ↑ Franics Haritigan Bill W. Chapter 25 p.190-197 and pages 170-171 St. Martins Press, year 2000, 1st edition, ISBN 0-312-20056-0

- ↑ Francis Hartigan, Bill W., Chapter 25, p. 190-197 and p. 170-171, St. Martins Press, 2000, 1st edition, ISBN 0-312-20056-0

- ↑ Francis Hartigan Bill Wilson p. 177-179.

- ↑ Pass It On': The Story of Bill Wilson and How the A. A. Message Reached the World. p. 370-371.

- ↑ Bill Wilson "The Best of Bill: Reflections on Faith, Fear, Honesty, Humility, and Love" p. 94-95

- ↑ LSD could help alcoholics stop drinking, AA founder believed The Guardian, 23 August 2012.

- ↑ {{cite web|url=http://www.doctoryourself.com/Hoffer2009int.pdf%7Ctitle=An Interview with Abram Hoffer], by [[Andrew W. Saul (nutrition specialist)-Andrew W. Saul]|publisher=}}

- ↑ Francis Hartigan Bill W P.205-208

- ↑ Robert Fitzgerald. The Soul of Sponsorship: The Friendship of Fr. Ed Dowling, S.J. and Bill Wilson in Letters. Hazelden Publishing & Educational Services: 1995. ISBN 978-1-56838-084-1. p 59.

- ↑ Harigan, Francis, Bill W.

- ↑ Ernest Kurtz. Not-God: A History of Alcoholics Anonymous. Hazelden Educational Foundation, Center City, MN, 1979. p 136.

- ↑ Alcoholics Anonymous, 4th ed., 2001, p. xxiii

- ↑ Griffith Edwards. Alcohol: The World's Favorite Drug. 1st U.S. ed. New York : Thomas Dunne Books, 2002. ISBN 0-312-28387-3. p 109.

- ↑ Are we making the most of Alcoholics Anonymous? Peter Armstrong. The Journal of Addiction and Mental Health 5.1, Jan-Feb 2002. p16.

- ↑ Cheever, 2004, p 122.

- ↑ Cheever, 1999.

- ↑ Time 100 Most Important Archived March 20, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Alcoholics Anonymous Founder’s House Is a Self-Help Landmark. New York Times. July 6, 2007

- ↑ "Interior Designates 27 New National Landmarks" (Press release). U.S. Department of the Interior. October 17, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ↑ When Love Is Not Enough: The Lois Wilson Story on IMDb

- ↑ Linden, Sheri (18 May 2012). "'Bill W.' cuts through the anonymity". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ Guitar Center (4 February 2013). "El Ten Eleven "Thanks Bill" At: Guitar Center" – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Sober Songs, Vol. 1". Sober Songs, Vol. 1.

Sources and further reading

- The A.A. Service Manual combined with Twelve Concepts for World Service (PDF) (2015-2016 ed.). New York: Alcoholics Anonymous. 2015.

- Susan Cheever. My Name is Bill, Bill Wilson: His Life and the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous. New York: Simon & Schuster/ Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0-7434-0591-1.

- Alcoholics Anonymous. The Story of How Many Thousands of Men and Women Have Recovered from Alcoholism (4th ed. new and rev. 2001 ed.). New York: Alcoholics Anonymous. ISBN 1-893007-16-2. ('Big Book')

- Alcoholics Anonymous Comes Of Age. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous. ISBN 0-916856-02-X.

- As Bill Sees It. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous. 1967. ISBN 0-916856-03-8.

- B., Dick (2006). The Conversion of Bill W.: More on the Creator's Role in Early A.A. Kihei, Hawaii: Paradise Research Publications, Inc., 96753. ISBN 1-885803-90-7.

- Bill W. (2000). My First 40 Years. An Autobiography by the Cofounder of Alcoholics Anonymous. Center City, Minnesota: Hazelden, 55012-0176. ISBN 1-56838-373-8.

- Dr. Bob and the Good Oldtimers. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous. 1980. ISBN 0-916856-07-0. LCCN 80-65962.

- Hartigan, Francis (2000). Bill W. A Biography of Alcoholics Anonymous Cofounder Bill Wilson. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 0-312-20056-0.

- Kurtz, Ernest (1979). Not-God: A History of Alcoholics Anonymous. Center City, Minnesota: Hazelden. ISBN 0-89486-065-8. LCCN 79-88264.

- Pass It On: The story of Bill Wilson and how the A.A. message reached the world. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous. 1984. ISBN 0-916856-12-7. LCCN 84-072766.

- Raphael, Matthew J. (2000). Bill W. and Mr. Wilson: The Legend and Life of A.A.'s Cofounder. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-55849-245-3.

- Thomsen, Robert (1975). Bill W. New York: Harper & Rowe. ISBN 0-06-014267-7.

- Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous. 1953. ISBN 0-916856-01-1.

- Faberman, J. & Geller, J. L. (January 2005). "My Name is Bill: Bill Wilson--His life and the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous". Psychiatric Services. 56 (1): 117. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.117.

- Galanter, M. (May 2005). "Review of My Name Is Bill: Bill Wilson—His Life and the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous". American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (5): 1037–1038. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.1037.

External links

- Bibliowiki has original media or text related to this article: William Griffith Wilson (in the public domain in Canada)