Big Game (American football)

| First meeting |

March 19, 1892 Stanford 14, California 10 |

|---|---|

| Latest meeting |

November 18, 2017 Stanford 17, California 14 |

| Next meeting | November 17, 2018 |

| Trophy | Stanford Axe |

| Statistics | |

| Meetings total | 120 |

| All-time series |

|

| Largest victory | Stanford, 63–13 (2013) |

| Longest win streak | Stanford, 8 (2010–present) |

| Current win streak | Stanford, 8 (2010–present) |

|

Locations of the two universities in the Bay Area | |

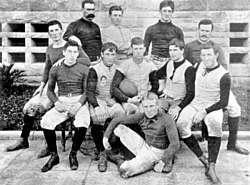

The Big Game is the name given to the Cal–Stanford football rivalry.[1][2] It is an American college football rivalry game played by the California Golden Bears football team of the University of California, Berkeley and the Stanford Cardinal football team of Stanford University. First played in 1892, it is one of the oldest college rivalries in the United States. Stanford leads the series 63-46-11. The game is typically played in late November or early December, and its location alternates between the two universities every year. In even-numbered years, the game is played at Berkeley, while in odd-numbered years it is played at Stanford.

Series history

Big Game is the oldest college football rivalry in the West.

While an undergraduate at Stanford, future U.S. President Herbert Hoover was the student manager of both the baseball and football teams. He helped organize the inaugural Big Game, along with his friend Cal manager Herbert Lang.[3] Only 10,000 tickets were printed for the game but 20,000 people showed up. Hoover and Lang scrambled to find pots, bowls and any other available receptacles to collect the admission fees.[4][5]

In 1898, Berkeley alumnus and San Francisco Mayor James D. Phelan purchased a casting of Douglas Tilden's The Football Players bronze sculpture and offered it as a prize to the school that could win the football game two years in a row. Berkeley responded by shutting Stanford out in 1898 and 1899, and the sculpture was installed on the Berkeley campus atop a stone pedestal engraved with the names of the players and the donor during a dedication ceremony held May 12, 1900.[6][7]

The term "Big Game" was first used in 1900, when it was played on Thanksgiving Day in San Francisco. During that game, a large group of men and boys, who were observing from the roof of the nearby S.F. and Pacific Glass Works, fell into the fiery interior of the building when the roof collapsed, resulting in 13 dead and 78 injured.[8][9][10][11][12] Fred Lilly, the last victim of the disaster, died on December 4, 1900, bringing the death toll to 22. To this day, the "Thanksgiving Day Disaster" remains the deadliest accident to kill spectators at a U.S. sporting event.[13]

In 1906, citing concerns about the violence in football, both schools dropped football in favor of rugby, which was played for the Big Games of 1906–14.[14][15] The first incidence of card stunts was performed by Cal fans at the halftime of the 1910 Big Game.[16]: 34–60

California resumed playing football in 1915, but Stanford's rugby teams continued until 1917. From 1915 to 1917, California's "Big Game" was their game against Washington, while Stanford played Santa Clara as their rugby "Big Game".[17] The 1918 game, in which Cal prevailed 67–0, is not considered an official game because Stanford's team was composed of volunteers from the Student Army Training Corps stationed at Stanford, some of whom were not Stanford students.[16]: 58 The game resumed as football in 1919, and has been played as such every year since, except from 1943 to 1945, when Stanford shut down its football program due to World War II. A handful of Stanford starters—including guards Jim Cox, Bill Hachten and Fred Boensch, running back George Quist and halfback Billy Agnew—shifted to Cal in order to continue playing.[18][19] Quist returned to Stanford, playing against Cal in the 1946 Big Game.

Scenes for the Harold Lloyd silent classic The Freshman were filmed at California Memorial Stadium during halftime of the 1924 Big Game.

Since 1933, the victor of the game has been awarded possession of the Stanford Axe. If a game ended in a tie, the Axe stayed on the side that already possessed it; this rule became obsolete in 1996 when the NCAA instituted overtime. The Axe is a key part of the rivalry's history, having been stolen on several occasions by both sides, starting in 1899, when the Axe was introduced when Stanford yell leader Billy Erb used it at a baseball game between the two schools.[20]

In March 2007, the National Football League announced that it intended to trademark the phrase "The Big Game" in reference to the Super Bowl,[21] but soon dropped the plan after being faced with opposition from Cal and Stanford.[22]

In 2013, the new Levi's Stadium in Santa Clara was proposed as the site of the 2014 Big Game, which according to the traditional rotation should be played at Cal's Memorial Stadium.[23] The 2015 game would then be held in Berkeley, reversing the current rotation of odd-numbered years at Stanford and even-numbered years at Cal.[24] But several days later Cal declined the offer.[25]

Pregame traditions

.jpg)

In the week before the game, both schools celebrate the occasion with rallies, reunions, and luncheons. Cal students hold a traditional pep rally and bonfire at the Hearst Greek Theatre on the eve of the game, while Stanford students stage the Gaieties, a theatrical production that both celebrates and pokes fun at the rivalry. The week also includes various other athletic events including "The Big Splash" (water polo), "The Big Spike" (volleyball), "The Big Sweep" (Quidditch),[26] "The Big Freeze" (ice hockey), "The Big Sail" (sailing), and the Ink Bowl, a touch football game between the members of the two schools' newspapers. In addition, the two schools compete in a blood drive called "Rivals for Life."

Cal

The Big Game Bonfire Rally is a pep and bonfire rally that takes place at University of California, Berkeley in Hearst Greek Theatre on the eve of Big Game. More than 10,000 students gather to hear the history about The Stanford Axe and Big Game. The University of California Rally Committee is in charge of the planning and setting up the bonfire, as well as refueling it during the rally. Specifically, freshman members of the UC Rally Committee, as well as freshman band members are sent out with pallets to the chanting of "freshmen, more wood." Several alumni show up to perform traditional rituals. A tradition unique to Cal is the performance of the Haka, a traditional Maori war dance/chant. Traditionally performed by an alumni Yell Leader, the Haka performed was written in the 1960s by a Cal rugby player of Maori descent. The traditional Axe Yell is also made and visits from the UC Men's Octet and Golden Overtones are always expected. The University of California Marching Band is also present, playing traditional Cal songs throughout the duration of the Rally. The highlight of the Rally is the lighting of Big Game Bonfire itself, with the fire reaching its zenith at over eight stories.

The Big Game Bonfire Rally always ends with the reciting of a speech known as the "Andy Smith Eulogy" or "The Spirit of California". Written by Garff Wilson in remembrance of the fabled Cal football coach, who led the Bears to five straight undefeated seasons starting in 1919 before tragically dying of pneumonia in 1925, the speech closes the Rally annually since 1949. During the speech, candles are passed out among the attendants and are lit for the singing of the campus alma mater, "All Hail Blue and Gold."[27][28]

In 2012, the Big Game Bonfire Rally was moved to Edwards Stadium and the bonfire was cancelled due to a scheduling conflict with a Bob Dylan concert. Due to TV contracts, the Pac-12 Conference rescheduled the Big Game from its traditional season-ending slot to October 20, and the Greek Theatre was already booked for the Bob Dylan concert. This was the first time the bonfire had not been held since 1892.[27] The bonfire portion of the rally was cancelled again in 2015 due to the ongoing drought.[29]

Stanford

For decades, Stanford also held a bonfire on the dry lakebed of Lake Lagunita, but this was discontinued in the 1990s due to the lake being a habitat for the vulnerable California tiger salamander.[30] Stanford now holds a Big Game Rally on Angell Field organized by the Stanford Axe Committee. With appearances from the senior football players and various performance groups, it serves to kick off Big Game Week. The story of The Stanford Axe is told by Hal Mickelson, and the Axe Yell is performed by the Yell Leaders of The Stanford Axe Committee. The rally ends with a performance by the Leland Stanford Junior University Marching Band and a fireworks show. A student-produced play called "Gaieties," an annual Big Game week tradition since 1911, pokes fun at Cal and serves to pump students up for the Big Game.[31] Another part of Stanford's tradition was the annual hanging of the substantial "Beat Cal" banner upon the four story Meyer Library building. This tradition came to an end in 2014 before the building was demolished.[32] Since 2015, the banner has been hung on the western facade of Green Library.

Notable games

1924

Both teams came into the game unbeaten with a berth in the 1925 Rose Bowl on the line. With its star Ernie Nevers sidelined due to injuries, Stanford trailed 20–6 with under 5 minutes to go, but rallied to score twice to force a 20–20 tie and earn the Rose Bowl bid.[33]

1947

In the 50th Big Game, winless Stanford led the 8–1 Bears with less than three minutes left in the game, but Cal scored on an 80-yard touchdown pass to clinch a 21–18 victory.[34]

1959

Stanford quarterback Dick Norman threw for 401 yards (then an NCAA record, and still a Big Game record), but it was not enough to hold off the Bears, who won 20–17.[34]

1972

Cal drove 62 yards in the final 1:13, culminating in a Vince Ferragamo touchdown pass to Steve Sweeney for a last-second 24–22 Cal victory.[35]

1974

Mike Langford nailed a 50-yard field goal on the final play for a 22–20 Stanford triumph over the 19th-ranked Bears.[35]

1982

The Play

The conclusion of the 85th Big Game on November 20, 1982 would go down as perhaps the most remarkable play in college football history. Cal held a lead late in the game, but Stanford, led by John Elway, drove down the field to retake the lead, and seemingly elevate Elway to the first bowl game of his college career, since a Stanford victory would have resulted in an invitation to the Hall of Fame Bowl.[36]

In what is now known simply as "The Play," four Cal players lateraled the ball five times on a kickoff return with four seconds left on the clock. Kevin Moen, who was also the initial ball carrier, ran for a touchdown while knocking down the final Stanford "defender," trombone player Gary Tyrrell, who had run onto the field with the rest of the band to celebrate prematurely.

The Play is often recounted with KGO radio announcer Joe Starkey's emotional call of The Play, which he hailed as "the most amazing, sensational, dramatic, heartrending, exciting, thrilling finish in the history of college football!" The legitimacy of The Play has remained controversial among some Stanford fans. The final score in the official record shows Cal winning by a score of 25–20, whereas in many Stanford publications it is recorded as Stanford 20, Cal 19 due to Stanford's contention that a Cal ball carrier had his knee down and the last lateral was actually an illegal forward pass, either of which would have resulted in the end of the play.

1988

With the score tied, Cal marched to the Stanford 3-yard line with 4 seconds remaining in the game. Called "the Cadillac of kickers in college football" by Cal coach Bruce Snyder, all Pac-10 and future all-American Robbie Keen lined up for a 21-yard field goal attempt to win the game on the final play. When the ball was snapped, Stanford redshirt freshman Tuan Van Le raced from the left end of the defensive line to block the kick and preserve a 19–19 tie. As Stanford was the holder of the Axe going into the game, the tie meant the Axe returned to the Farm for another year. The result was celebrated in the stadium as a victory by Stanford as the Axe was paraded by the Stanford Axe Committee and football players before jubilant Cardinal fans, with stunned Bear fans looking on. This was the only Big Game to end in a tie after 1953 and under current overtime rules may be the last Big Game to end tied.[34]

1990

This game had echoes of the 1982 game due to late seesaw scoring, the critical role of fans on the field, and the winning points being scored as time expired. It has been called "The Payback" or "The Revenge of the Play" by Stanford fans.[37] After trailing since the first quarter, left-footed Stanford kicker John Hopkins kicked his fourth field goal of the game with 9:56 left to give Stanford its first lead at 18–17. Cal responded with a touchdown and added a two-point conversion to lead 25-18 with 6:03 left. Stanford stopped Cal on a third and 6 on the Stanford 46 with 2:06 left to play. After Cal's punt, Stanford took its final possession on its own 13 with 1:54 left. Escaping two near interceptions and converting a 4th and 6, Stanford moved the ball to the Cal 19 with 0:17 left. Quarterback Jason Palumbis threw a touchdown pass to Ed McCaffrey in the end zone to make it 25–24. With no overtime, and despite the fact that a tie would keep the Axe at Stanford for another year, Cardinal coach Dennis Green quickly went for a two-point conversion. The attempt failed and Cal fans and players engulfed the field, causing a lengthy delay and resulting in a 15-yard delay of game penalty. With 12 seconds left and now kicking from the 50 yard line, Hopkins bounced the ensuing onside kick off a Cal player and, after being touched by seven players, the ball was recovered by Stanford's Dan Byers on the Cal 37. With 9 seconds left and no time outs, a pass attempt to McCaffrey to set up a field goal fell short, but Palumbis was roughed on the play moving the ball to the 22 yard line. With 5 seconds left, Hopkins connected on a 39-yard field goal into the wind, giving Stanford a 27–25 victory as time expired. This time Stanford students and players engulfed the field. The late passing and kicking excitement overshadowed two excellent running performances by Cal's Russell White (177 yards and 2 TD's) and Stanford's Glyn Milburn (196 yards and 1 TD). Milburn also led Stanford receiving with 9 receptions for 66 yards and had 117 return yards. His 379 all-purpose yards set a Pac-10 record at the time and remained Stanford's record until it was eclipsed by Christian McCaffrey's 389 all-purpose yards in the 2015 edition of the Big Game.[38]

2000

Stanford's Casey Moore caught the winning touchdown on the final play of the first-ever Big Game to go into overtime.[34]

2009

Cal's Michael Mohamed intercepted an Andrew Luck pass at the Cal 3-yard line with 1:36 left to preserve a Cal win over #14 Stanford, 34–28.[39]

2010

Sixth-ranked Stanford, in a 48–14 victory, ties Cal's 1975 record for most points scored in a Big Game.[40]

2013

Winning 63–13, #10 Stanford set the record for most points scored in a Big Game, shattering the previous record of 48 shared by Cal in 1975 and Stanford in 2010. The 50-point victory margin also set a Big Game record, breaking the previous record that had stood for 83 years when Stanford beat Cal 41-0 in 1930. The 76 total points scored by both teams broke the record of 66 set in 2000. With the victory, Stanford clinched the Pac-12 North Division Championship while Cal ended its season at 1–11, the most losses in one season in Cal football history.[41]

Game results

Note: This chart lists the official Big Games between Stanford and Cal.

| California victories | Stanford victories | Ties |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Notes

- ↑ From 1906 to 1914, "football" was played under Australia-New Zealand modified rugby rules per an agreement between Stanford and Cal coaches.[42]

- ↑ In 1915, Cal switched back to the East Coast-style "gridiron" rules, following the lead of the Los Angeles-area universities. The Big Game was played in the years 1915–17, but against Washington. Those games aren't listed in Big Game records. The reason for Stanford's not playing those years was not World War I, as has been stated here, but because of a disagreement over allowing freshmen to play on the varsity. A game was played in 1918, but the Stanford team consisted of military students or others, not varsity football players. Cal won 72-0. In 1919, Stanford switched back to "gridiron" rules.[42]

- ↑ The rivalry was suspended in 1943-45 for World War II.

Rivalry in other sports

In other sports, matchups between Cal and Stanford are not as important to the students and the fanbase, but are still hyped and many feature their own nicknames based on the word "big." Examples include:

- Men's and women's rowing - The "Big Row" now in honor of Cal coxswain Jill Costello who died of stage 4 lung cancer in 2010.

- Men's and women's track and field - The "Big Meet"

- Volleyball – The "Big Spike"[43]

- Men's basketball - The "Big Tipoff"

- Water polo – The "Big Splash"[43]

- Ice hockey – The "Big Freeze"

- Sailing - The "Big Sail,"[43] held at St. Francis Yacht Club in San Francisco

- Quidditch - The "Big Sweep"

In rugby, the two schools have a trophy of their own called the "Scrum Axe". In men's basketball the semiannual matchups are sometimes labeled the "Big Game" but it is not official. In women's basketball, the meetings are simply called the "Battle of the Bay."

See also

References

- ↑ https://www.mercurynews.com/2017/11/18/cal-makes-stanford-work-for-it-but-falls-in-120th-big-game/

- ↑ https://www.ruleoftree.com/2017/11/14/16652110/history-big-game-stanford-cal

- ↑ Big Games: College Football's Greatest Rivalries - Page 222

- ↑ Big Games: College Football's Greatest Rivalries - Pages 221-222

- ↑ Herbert Hoover: Life Before the Presidency

- ↑ Finacom, Steven (6 August 2010). "Famed Deaf Sculptor Died 75 Years Ago in Berkeley". The Berkeley Daily Planet. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ "Douglas Tilden 1860-1935". Gay Bears! The Hidden History of the Berkeley Campus. Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley. 2002. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ A Ghastly Holocaust: Football Spectators Plunged into Molten Glass, The (Adelaide) Advertiser, (Friday 11 January 1901), p.6.

- ↑ Twenty Score Persons Make Awful Plunge: Seventeen People Meet Most Awful Death: Two San Jose Men Die Amid Sizzling Shrieking Human Mass in Collapsed Factory at Big Game, The (San Jose) Evening News, (Friday 30 November 1900), p.1, p.5.

- ↑ Through a Roof to Death, The (Crawfordsville) Daily News-Review, (Friday, 30 November 1900), p.2.

- ↑ Spectators Fell Into Molten Glass: Thirteen Dead, One Hundred Injured by Collapse of a Roof Overlooking the Stanford-Berkeley Game at San Francisco, The (Spokane) Spokesman-Review, (Friday 30 November 1900), p.1.

- ↑ Death Reaps a Dread Harvest of Lives and Plunges City into Gloom, The San Francisco Call, (Friday, 30 November 1900), p.2.

- ↑ Eskanazi, J., "Sudden Death: Boys Fell to Their Doom in S.F.'s Forgotten Disaster", San Francisco Weekly News, 15 August 2012.

- ↑ "Many changes in rugby game". The Evening News (San Jose). September 14, 1906. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- ↑ Elliott, Orrin Leslie (1937). Stanford University – The First Twenty Five Years 1891–1925. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 231–233. ISBN 9781406771411. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- 1 2 Migdol, Gary (1997). Stanford: Home of Champions. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC. ISBN 1-57167-116-1.

- ↑ Park, Roberta J (Winter 1984). "From Football to Rugby—and Back, 1906–1919: The University of California–Stanford University Response to the "Football Crisis of 1905"" (PDF). Journal of Sport History. 11 (3): 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-07.

- ↑ "Bob Murphy Shares His Love of the Tradition of The Big Game: Murphy has been broadcasting Stanford football for over 40 years". Cardinal Athletics. Stanford University. November 17, 2005. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ↑ Snapp, Martin (Winter 2011). "Alumni Gazette". California. Cal Alumni Association. 122 (4): 72. ISSN 0008-1302.

- ↑ "The Stanford Axe- Origin and Loss of the Axe". www.stanford.edu. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ↑ FitzGerald, Tom (August 23, 2010). "NFL marketers want 'Big Game' trademark; Cal, Stanford fight to protect symbol of football rivalry". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ FitzGerald, Tom (August 22, 2010). "NFL sidelines its pursuit of Big Game trademark". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ "Cal, Stanford consider moving Big Game to Levi's Stadium". KGO-TV. August 24, 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Kroichick, Ron (August 24, 2013). "Cal ponders moving 2014 Big Game". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Faraudo, Jeff (August 29, 2013). "Cal opts against Big Game at Levi's Stadium". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ↑ "Cal & Stanford Create Inaugural Division I Quidditch Teams". California Golden Blogs. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- 1 2 Jones, Carolyn (30 July 2012). "Cal Big Game bonfire tradition doused". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ "Andy Smith Eulogy". Calisphere. University of California. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ↑ Yen, Ruey (25 October 2015). "No traditional bonfire at the 2015 Big Game Rally due to drought". California Golden Blogs. SB Nation. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ "Bonfire canceled to protect salamander habitat" (Press release). Stanford University. October 7, 1993.

- ↑ MacLeod, Madeline (November 20, 2015). "'Gaieties: Chem 31 XXX' is the best class all quarter". The Stanford Daily. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ "Stanford's Meyer Library to be replaced with open space". 2017-03-11. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ↑ Breier, John (November 18, 2009). "A Come-Through Story: The 1924 Big Game". Scout.com. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Big Game History and Tradition". GoStanford.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- 1 2 "The Big Game: Cal vs. Stanford". Scout.com. November 22, 2009. Archived from the original on 2017-05-25. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Stanford Cards get bowl bid". The Bulletin. November 16, 1982. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ↑ Faraudo, Jeff (November 17, 2010). "1990: When Stanford staged its Revenge of The Play". East Bay Times. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ Peters, Keith (November 19, 1997). "Big Game Flashback". Palo Alto Weekly. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Cal beats #14 Stanford 34–28 in Big Game". abcnews.com. November 21, 2009. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Cal Football Postgame Notes – 113th Big Game vs. Stanford (Sat., Nov. 20)". CBS Interactive. November 20, 2010. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ↑ FitzGerald, Tom (November 23, 2013). "Stanford routs Cal, reaches Pac-12 title game". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- 1 2 Ingrassia, Brian M. (2017). "3. Reforming the Big Game: the Bay Area Rugby Experiment of 1906–1919". In Liberti, Rita; Smith, Maureen. San Francisco Bay Area Sports: Golden Gate Athletics, Recreation, and Community. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. pp. 43–58. ISBN 978-1-61075-603-7. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 Roethel, Kathryn (2010-11-20). "For Stanford and Cal, Big Game week in every sport". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2014-12-14.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Big Game. |