Bicentennial Man (film)

| Bicentennial Man | |

|---|---|

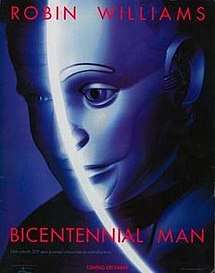

Promotional poster | |

| Directed by | Chris Columbus |

| Produced by |

Chris Columbus Wolfgang Petersen Gail Katz Laurence Mark Neal Miller Mark Radcliffe Michael Barnathan |

| Screenplay by | Nicholas Kazan |

| Based on |

The Positronic Man by Isaac Asimov Robert Silverberg The Bicentennial Man by Isaac Asimov |

| Starring | |

| Music by | James Horner |

| Cinematography | Phil Méheux |

| Edited by | Neil Travis |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

Buena Vista Pictures Distribution (United States & Canada) Columbia TriStar Film Distributors International (International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 132 minutes |

| Country |

United States Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $100 million |

| Box office | $87.4 million |

Bicentennial Man is a 1999 Canadian-American science fiction comedy-drama film starring Robin Williams, Sam Neill, Embeth Davidtz (in a dual role), Wendy Crewson, and Oliver Platt. Based on the novel The Positronic Man by Isaac Asimov and Robert Silverberg (which is itself based on Asimov's original novella of the same name), the plot explores issues of humanity, slavery, prejudice, maturity, intellectual freedom, conformity, sex, love, and mortality. The film, a co-production between Touchstone Pictures and Columbia Pictures, was directed by Chris Columbus. The title comes from the main character existing to the age of two hundred years, and Asimov's novella was published in the year the United States had its bicentennial.

Despite being a box office bomb, makeup artist Greg Cannom was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Makeup at the 72nd Academy Awards, and the film has drawn a cult following. The theme song of the film which was written by James Horner and Will Jennings and sung by Celine Dion is "Then You Look at Me".[1]

Plot

The NDR series robot "Andrew" is introduced in 2005 into the Martin family home to perform housekeeping and maintenance duties. The family's reactions range from acceptance and curiosity, to outright rejection, and deliberate vandalism by their rebellious older daughter, Grace, who treats him as a mere robot and continues with her rebellious ways while growing up. This leads Andrew to discover that he can both identify emotions and reciprocate in kind. When Andrew accidentally breaks a figurine belonging to "Little Miss" Amanda, he carves a replacement out of wood, as way to apologize to her. The family is astonished by this creativity and “Sir” Richard Martin takes Andrew to his manufacturer, to inquire if all the robots are like him. The CEO of the company, Dennis Mansky, sees this development as a problem and wishes to scrap Andrew. Angered, Richard takes Andrew home and allows him to pursue his own development, encouraging Andrew to educate himself in the humanities.

Years later, Martin again takes Andrew to NorthAm Robotics for repairs following an accident in which his thumb is accidentally cut off. Richard ensures first that Andrew's personality will remain un-tampered with. Andrew requests his face be altered to convey the emotions he feels but cannot fully express, while he is being repaired. Twelve years later, Andrew eventually asks for his freedom, much to Richard's dismay. He grants the request, but banishes Andrew so he can be 'completely' free. Andrew builds himself a home and lives alone. In 2048, Andrew sees Richard one last time on his deathbed, where he apologizes for banishing him.

Andrew goes on a quest to locate more NDR series robots to discover if others have also developed sentience. After nearly twenty years of failure, he finds Galatea, an NDR robot that has been given feminine attributes and personality. These, however, are simply aspects of her programming and not something which she spontaneously developed. Galatea is owned by Rupert Burns, son of the original NDR robot designer. Burns works to create more human-looking robots, but is unable to attract funding. Andrew agrees to finance the research and the two join forces to revolutionize robotics. He meanwhile maintains contact with Amanda, who grew up, married, had a child, divorced and now has a granddaughter called Portia. After receiving human features, Andrew comes back home, and sees Amanda, now aged, with Portia, who is the same as her grandmother in her younger years. Initially he has some troubles reintegrating into the family since now there is only Amanda who actually knows him, but he manages to befriend Portia.

Some time later, Amanda passes away, leaving Andrew to realise that everyone he knows will die one day. Accepting this fact, Andrew decides to become human. With the help of Rupert, he creates a new type of mechanical organs that can be used both by him to become more human and used by humans as prosthetic organs. He gains a nervous system and lots of other organs that make him able to eat, to feel emotions and sensations, and also to have sexual intercourse. Eventually, Andrew becomes human enough to fall in love with Portia and, ultimately, she falls in love with him.

Over the course of the next century, Andrew petitions the World Congress to recognize him as human, which would allow him and Portia to be legally married, but is rejected; the Speaker of the Congress explains that society can tolerate an everlasting machine, but argues that an immortal human would create too much jealousy and anger. Initially Andrew decides to make Portia live as much as possible through his medical inventions but after some decades she tells him that she can't and doesn't want to live forever, so one day she will refuse any more treatment. Andrew decides to make Burns inject blood into his system, thereby allowing him to age, and thus he begins to grow old alongside Portia.

Andrew again attends the World Congress with Portia, both now appearing old and frail, and again petitions to be declared a human being. On their death bed with life support, Andrew and Portia watch as the Speaker of the World Congress announces on television the court's decision: that Andrew is officially recognized as human, and (aside from "Methuselah and other Biblical characters") is the oldest human being in history at the age of two-hundred years old. The Speaker also validates the marriage between Portia and Andrew. Andrew dies while listening to the broadcast despite his life support, and Portia orders their nurse Galatea, a now recognizably-human android, to unplug her life support. Portia dies hand-in-hand with Andrew after she whispers "See you soon" to him.

Cast

- Robin Williams as Andrew Martin, an NDR android servant of the Martin family that seeks to become human.

- Sam Neill as Richard "Sir" Martin, the patriarch of the Martin family.

- Embeth Davidtz as Amanda "Little Miss" Martin (adult) as well as Portia Charney, the daughter of Lloyd and the granddaughter of Amanda.

- Hallie Kate Eisenberg as Amanda "Little Miss" Martin (age 7)

- Wendy Crewson as Rachel "Ma´am" Martin, the matriarch of the Martin family.

- Oliver Platt as Rupert Burns, the son of the NDR creator that makes his androids look more human-like.

- Kiersten Warren as Galatea, the NDR android servant of Rupert.

- Stephen Root as Dennis Mansky

- Angela Landis as Grace "Miss" Martin (adult)

- Lindze Letherman as Grace "Miss" Martin (age 9)

- Bradley Whitford as Lloyd Charney (adult)

- Igor Hiller as Lloyd Charney (age 10)

- John Michael Higgins as Bill Feingold

- George D. Wallace as the first President/Speaker of the World Congress

- Lynne Thigpen as Marjorie Bota, the second President/Speaker of the World Congress

Production

Williams confirmed in a Las Vegas Sun interview that his character was not played by a body double and that he had actually worn the robot costume.[2]

Reception

The film holds a 36% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 96 critical reviews, with an average rating of 4.8/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Bicentennial Man is ruined by a bad script and ends up being dull and mawkish."[3] The review aggregator Metacritic gives it a score of 42.[4]

Roger Ebert gave it two out of four stars:

| “ | Bicentennial Man begins with promise, proceeds in fits and starts, and finally sinks into a cornball drone of greeting-card sentiment. Robin Williams spends the first half of the film encased in a metallic robot suit, and when he emerges, the script turns robotic instead. What a letdown.[5] | ” |

William Arnold of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer said:

| “ | [The film] becomes a somber, sentimental and rather profound romantic fantasy that is more true to the spirit of the Golden Age of science-fiction writing than possibly any other movie of the '90s. | ” |

Todd McCarthy of Variety summed it up as "an ambitious tale handled in a dawdling, sentimental way."

Accolades

- Academy Awards — Best Makeup (lost to Topsy-Turvy)

- Blockbuster Entertainment Award — Favorite Actor — Comedy (Robin Williams) (lost to Adam Sandler in Big Daddy)[6]

- Blockbuster Entertainment Award — Favorite Actress — Comedy (Embeth Davidtz) (lost to Drew Barrymore in Never Been Kissed)[6]

- Hollywood Makeup Artist and Hair Stylist Guild Award — Best Character Makeup — Feature (lost to Sleepy Hollow)

- Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards — Favorite Movie Actor (Robin Williams) (lost to Adam Sandler in Big Daddy)

- Razzie Award — Worst Actor (Robin Williams) (lost to Adam Sandler in Big Daddy)

- YoungStar Award — Best Young Actress/Performance in a Motion Picture Comedy (Hallie Kate Eisenberg) (lost to Natalie Portman in Where the Heart Is)

References

- ↑ Broxton, Jonathan (December 17, 1999). "Bicentennial Man – James Horner". Movie Music UK. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ↑ Neil, Dave (23 December 1999). "Robin Williams reveals the mechanics of making 'Bicentennial Man'". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ↑ "Bicentennial Man (1999)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Bicentennial Man". Metacritic. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (December 17, 1999). "Bicentennial Man". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- 1 2 "Blockbuster Entertainment Award winners". Variety. May 9, 2000. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bicentennial Man (film) |