Betula alleghaniensis

| Yellow birch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Yellow Birch foliage | |

| |

| Bark | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Betulaceae |

| Genus: | Betula |

| Subgenus: | Betula subg. Betulenta |

| Species: | B. alleghaniensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Betula alleghaniensis Britt. | |

| |

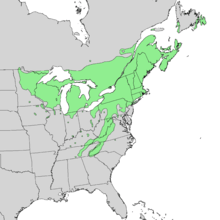

| Natural range of Betula alleghaniensis | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Betula alleghaniensis (yellow birch[1] or golden birch), is a large and important lumber species of birch native to North-eastern North America. The name "yellow birch" reflects the color of the tree's bark.[2] The name Betula lutea was used expansively for this tree but has now been replaced.

Betula alleghaniensis is the provincial tree of Quebec, where it is commonly called merisier, a name which in France is used for the wild cherry.

Description

It is a medium-sized, typically single stemmed, deciduous tree reaching 60–80 feet (18–24 m) tall (exceptionally to 100 ft (30 m))[1][3] with a trunk typically 2–3 ft (0.61–0.91 m) in diameter.[1][4] Yellow birch is a relatively long lived birch which typically grows 150 years and may even grow up to 300 in old growth forests.[5]

It mostly reproduces by seed. Mature trees typically start producing seeds at about 40 years but may start as young as 20.[5] The optimum age for seed production is about 70 years. Good seed crops are not produced every year, and tend to be produced in intervals of 1–4 years with the years between good years having little seed production. The seeds germinate best on mossy logs, decaying wood or cracks in boulders since they cannot penetrate the leaf litter layer.[5] Yellow birch saplings will not establish in full shade (under a closed canopy) so they typically need disturbances in a forest in order to establish and grow.

- The bark on mature trees is a shiny yellow-bronze which flakes and peels in fine horizontal strips.[1][6] The bark often has small black marks and dark horizontal lenticels.[3] After the tree reaches a diameter greater than 1 ft the bark typically stops shredding and reveal a platy outer bark although the thinner branches will still have the shreddy bark.[7] There is an uncommon, alternate form of the tree (f. fallax) which grows in the southern part of the range.[1] F. fallax has darker gray-brown bark which shreds less than the typical form.[8]

- The twigs, when scraped, have a slight scent of wintergreen oil, though not as strongly so as the related sweet birch (B. lenta), which is the only other birch in North America to also smell of wintergreen.[1][6] However, the potency of the odor is not considered a reliable identification method unless it is combined with other characteristics.[1]

- The leaves are alternately placed on the stem, oval in shape with a pointed tip and often a slightly heart shaped (cordate) base. They are 2–5 in (5.1–12.7 cm) long and typically half as wide[4] with a finely serrated (doubly serrate) margin. They are dark green in color on the upper side and lighter on the bottom, the veins on the bottom are also pubescent.[4][8] The leaves arise in pairs or singularly from small spur shoots.[8] In the fall the leaves turn a bright yellow color.[7][9]

- The leaf has a very short petiole 1⁄4–1⁄2 in (1–1 cm) long.

- The flowers are wind-pollinated catkins which open in later spring.[3] Both male and female flowers will occur on the same tree making the plant monoecious. The male catkins are 2–4 in (5–10 cm) long, yellow purple, pendulous (hang downwards), and occur in groups of 3-6 on the previous year's growth. The female catkins are erect (point upward) and 1.5–3 cm (5⁄8–1 1⁄8 in) long and oval in shape, they arise from short spur branches with the leaves.[8] The fruit, mature in fall, is composed of numerous tiny winged seeds packed between the catkin bracts.[10]

- The seed is a winged samara with two wings which are shorter than the width of the seed which matures and gets released in autumn.[3]

Similarity to Betula lenta

Both yellow birch and sweet birch have nearly identical leaf shape and both give an odor of wintergreen when crushed. To differentiate the two species, the range, buds, or bark must be examined. The ranges do overlap in Appalachia where they commonly grow together, but sweet birch does not grow west of Ohio or north into Canada whereas yellow birch does.[1] Sweet birch also has black non-peeling bark compared to the lighter, bronze colored, peeling bark of yellow birch. For young trees where bark has not yet developed, yellow birch can also be identified by its has hairy buds and stems; sweet birch has hairless buds.[1]

Varieties

Two varieties have been recognized

- B. a. var macrolepis has scales on the fruiting catkins which measure 8–13 mm

- B. a. var alleghaniensis catkin scales 5–8 mm

Range and climate

Its native range extends from Newfoundland to Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, southern Quebec and Ontario, and the southeast corner of Manitoba in Canada, west to Minnesota, and south in the Appalachian Mountains to northern Georgia.[11] While its range extends as far south as Georgia, it is most abundant in the northern part of its range and only occurs in high elevations in the southern part of the range.[4][10] It grows in USDA zones 3-7.[4]

B. alleghaniensis prefers to grow in cooler conditions and is often found on north facing slopes, swamps, stream banks, and rich woods.[3][12] It does not grow well in dry regions or regions with hot summers. It grows soil pH ranging from 4-8.[9]

Ecology

The twigs are browsed on by whitetail deer, moose and cottontails[12] Deer eat many saplings and may limit regeneration of the species if the deer population is too great.[5] Ruffed grouse and various songbirds feed on the seeds and buds.[7] Due to the thin bark of the tree yellow bellied sapsuckers feed on this tree by drilling holes in the tree and collecting the sap.[8] Broad-winged hawks show a preference for nesting in yellow birch in New York.[13]

Several species of Lepidoptera including the mourning cloak (Nymphalis antiopa) and dreamy duskywing (Erynnis icelus) feed on B. alleghaniensis as caterpillars.[14]

Yellow birch is often associated with eastern hemlock throughout its range due to their similar preferences in habitat. It mostly grows from 0–500 m in elevation but may grow up to 1000 m.[5] It reaches its maximum importance in the transition zone between low elevation deciduous forests and high elevation spruce and fir forests. Due to the thin bark and lack of ability to resprout, it is easily killed by wildfire.[8]

Sugar maple (Acer saccharum) exerts allelopathic effects on seedlings of yellow birch and decreases their growth ability.[15][16] The inhibitory chemical is exuded from the roots of the sugar maple and has a very short soil half-life, it no longer has effects on birch after 5 days.[15]

Hybrids

- It hybridizes with Betula pumila to form Betula × purpusii in larch swamps. These hybrids are rather common[3] and shrubby in growth pattern and may have an odor of wintergreen or rusty-hairy twigs.[1] The leaf shape is intermediate between both species.[3]

- It can also hybridize with Betula papyrifera in northern regions where their ranges overlap. It has seldom been reported but is thought to be more common than realized.[3] In most features it is intermediate between the two parents.

Conservation status in the United States

Uses

Yellow birch is considered the most important species of birch for lumber and an important hardwood timber tree; as such, the wood of Betula alleghaniensis is extensively used for flooring, furniture, doors, veneer,cabinetry, gun stocks and toothpicks.[5][8][12] Most wood sold as birch in North America is from this tree. Its wood is relatively strong, close grained, and heavy. The wood varies in color from reddish brown to creamy white and accepts stain and can be worked to a high polish.[5]

In the past, yellow birch has been used for distilling wood alcohol, acetate of lime and for tar and oils.[12] Oil of wintergreen can be distilled from the bark.[4]

The papery, shredded bark, is very flammable and can be peeled off and used as a fire starter even in wet conditions.[12]

Yellow birch can be tapped for syrup similarly to sugar maple, and although the sap has less sugar content, it flows in greater quantity than sugar maple. When the sap is boiled down, the wintergreen evaporates and leaves a syrup not unlike maple syrup. The sap can also be used as is in birch syrup or may be flavored. Tea can also be made from the twigs and inner bark.[5]

Native American ethnobotany

Yellow birch has been used medicinally by Native Americans as a blood purifier and for other uses.[3][7] The Ojibwe make a compound decoction from the inner bark and take it as a diuretic.[18] They also make use of Betula alleghaniensis var. alleghaniensis, taking of the bark for internal blood diseases,[19] and mixing its sap and maple sap used for a pleasant beverage drink.[20] They use the bark of var. alleghaniensis to build dwellings, lodges, canoes, storage containers, sap dishes, rice baskets, buckets, trays and dishes and place on coffins when burying the dead.[21]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Peterson, George A. Petrides ; illustrations by George A. Petrides, Roger Tory (1986). A field guide to trees and shrubs : northeastern and north-central United States and southeastern and south-central Canada (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-13651-2.

- ↑ http://landscaping.about.com/cs/fallfoliagetrees/a/fall_foliage4.htm

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Furlow, John J. (1997). "Betula alleghaniensis". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee. Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 3. New York and Oxford. Retrieved 26 July 2016 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dirr, Michael A (1990). Manual of woody landscape plants (4. ed., rev. ed.). Champaign, Illinois: Stipes Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87563-344-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "YELLOW BIRCH PLANT GUIDE" (PDF). USDA plants. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- 1 2 Rhoads, Ann; Block, Timothy. The Plants of Pennsylvania (2 ed.). Philadelphia Pa: University of Pennsylvania press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4003-0.

- 1 2 3 4 "Trees of the Adirondacks: Yellow Birch | Betula alleghaniensis". www.adirondackvic.org. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hilty, John (2016). "Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis)". Illinois Wildflowers. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- 1 2 "Conservation Plant Characteristics for ScientificName (CommonName) USDA PLANTS". plants.usda.gov. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- 1 2 Erdmann, G. G. (1990). "Betula alleghaniensis". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2. Retrieved 14 July 2016 – via Southern Research Station (www.srs.fs.fed.us).

- ↑ "Plants Profile for Betula alleghaniensis (yellow birch)". plants.usda.gov. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Common Trees of Pennsylvania" (PDF). Envirothon pa. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Matray, Paul F. (1974). "Broad-Winged Hawk Nesting and Ecology". The Auk. 91: 307–324. JSTOR 4084510.

- ↑ "Butterflies in Your Backyard | NC State University". content.ces.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- 1 2 Tubbs, Carl H. (June 1973). "Allelopathic Relationship between Yellow Birch and Sugar Maple Seedlings". Forest Science. 19: 139–147. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Wenger, edited for the Society of American Foresters by Karl F. (1984). Forestry handbook (2nd ed.). New York ; Toronto: J. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-06227-8. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "Betula alleghaniensis". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ Hoffman, W.J., 1891, The Midewiwin or 'Grand Medicine Society' of the Ojibwa, SI-BAE Annual Report #7, page 199

- ↑ Reagan, Albert B., 1928, Plants Used by the Bois Fort Chippewa (Ojibwa) Indians of Minnesota, Wisconsin Archeologist 7(4):230-248, page 231

- ↑ Smith, Huron H., 1932, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians, Bulletin of the Public Museum of Milwaukee 4:327-525, page 397

- ↑ Reagan, Albert B., 1928, Plants Used by the Bois Fort Chippewa (Ojibwa) Indians of Minnesota, Wisconsin Archeologist 7(4):230-248, page 241

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Betula alleghaniensis. |