Caryophyllene

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

(1R,4E,9S)-4,11,11-Trimethyl-8-methylidenebicyclo[7.2.0]undec-4-ene | |

| Other names

β-Caryophyllene trans-(1R,9S)-8-Methylene-4,11,11-trimethylbicyclo[7.2.0]undec-4-ene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.588 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H24 | |

| Molar mass | 204.36 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 0.9052 g/cm3 (17 °C)[1] |

| Boiling point | 262–264 °C (504–507 °F; 535–537 K)[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

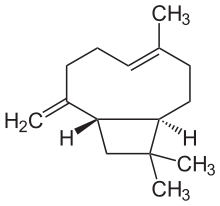

Caryophyllene /ˌkærioʊfɪˈliːn/, or (−)-β-caryophyllene, is a natural bicyclic sesquiterpene that is a constituent of many essential oils, especially clove oil, the oil from the stems and flowers of Syzygium aromaticum (cloves),[3] the essential oil of Cannabis sativa, rosemary,[4] and hops.[5] It is usually found as a mixture with isocaryophyllene (the cis double bond isomer) and α-humulene (obsolete name: α-caryophyllene), a ring-opened isomer. Caryophyllene is notable for having a cyclobutane ring, as well as a trans-double bond in a 9-membered ring, both rarities in nature.

The first total synthesis of caryophyllene in 1964 by E.J. Corey was considered one of the classic demonstrations of the possibilities of synthetic organic chemistry at the time.[6]

Caryophyllene is one of the chemical compounds that contributes to the spiciness of black pepper.[7]

Metabolism and derivatives

14-Hydroxycaryophyllene oxide (C15H24O2) was isolated from the urine of rabbits treated with (-)-caryophyllene (C15H24). The x-ray crystal structure of 14-hydroxycaryophyllene (as its acetate derivative) has been reported.

The metabolism of caryophyllen progresses through (-)-caryophyllene oxide (C15H24O) since the latter compound also afforded 14-hydroxycaryophyllene (C15H24O) as a metabolite.[8]

- Caryophyllene (C15H24) → caryophyllene oxide (C15H24O) → 14-hydroxycaryophyllene (C15H24O) → 14-hydroxycaryophyllene oxide (C15H24O2).

Caryophyllene oxide,[9] in which the olefin of caryophyllene has become an epoxide, is the component responsible for cannabis identification by drug-sniffing dogs[10][11] and is also an approved food flavoring.

Natural sources

The approximate quantity of caryophyllene in the essential oil of each source is given in square brackets ([ ]):

- Cannabis, hemp, marijuana (Cannabis sativa) [3.8–37.5% of cannabis flower essential oil][12]

- Black caraway (Carum nigrum) [7.8%][13]

- Cloves (Syzygium aromaticum)[3] [1.7–19,5% of clove bud essential oil][14]

- Hops (Humulus lupulus)[15] [5.1–14.5%][16]

- Basil (Ocimum spp.)[17] [5.3–10.5% O. gratissimum; 4.0–19.8% O. micranthum][18]

- Oregano (Origanum vulgare)[19] [4.9–15.7%][20][21]

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum) [7.29%][7]

- Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) [4.62–7.55% of lavender oil][22][23]

- Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis)[4] [0.1–8.3%][24]

- True cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) [6.9–11.1%][25]

- Malabathrum (Cinnamomum tamala) [25.3%][26]

- Ylang-ylang (Cananga odorata) [3.1–10.7%]

- Copaiba oil (Copaifera spp.)[27][28]

Compendial status

Notes and references

- ↑ SciFinder Record, CAS Registry Number 87-44-5

- ↑ Baker, Richard R. (2004). "The pyrolysis of tobacco ingredients". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 71 (1): 223–311. doi:10.1016/s0165-2370(03)00090-1.

- 1 2 Ghelardini C, Galeotti N, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Mazzanti G, Bartolini A (2001). "Local anaesthetic activity of beta-caryophyllene". Farmaco. 56 (5–7): 387–9. doi:10.1016/S0014-827X(01)01092-8. PMID 11482764.

- 1 2 Ormeño E, Baldy V, Ballini C, Fernandez C (September 2008). "Production and diversity of volatile terpenes from plants on calcareous and siliceous soils: effect of soil nutrients". J. Chem. Ecol. 34 (9): 1219–29. doi:10.1007/s10886-008-9515-2. PMID 18670820.

- ↑ Glenn Tinseth, "Hop Aroma and Flavor", January/February 1993, Brewing Techniques. <http://realbeer.com/hops/aroma.html> Accessed July 21, 2010.

- ↑ Corey EJ, Mitra RB, Uda H (1964). "Total Synthesis of d,l-Caryophyllene and d,l-Isocaryophyllene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 86 (3): 485–492. doi:10.1021/ja01057a040.

- 1 2 Jirovetz L, Buchbauer G, Ngassoum MB, Geissler M (November 2002). "Aroma compound analysis of Piper nigrum and Piper guineense essential oils from Cameroon using solid-phase microextraction-gas chromatography, solid-phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and olfactometry". J Chromatogr A. 976 (1–2): 265–75. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(02)00376-X. PMID 12462618.

- ↑ Pubchem. "Caryophyllene oxide | C15H24O - PubChem". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- ↑ Yang, D.; Michel, L.; Chaumont, J. P.; Millet-Clerc, J. (1999-11-01). "Use of caryophyllene oxide as an antifungal agent in an in vitro experimental model of onychomycosis". Mycopathologia. 148 (2): 79–82. doi:10.1023/A:1007178924408. ISSN 0301-486X. PMID 11189747.

- ↑ Ethan (2011). "Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects". Br J Pharmacol. 163 (7): 1344–1364. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x. PMC 3165946. PMID 21749363.

- ↑ Stahl, E; Kunde, R (1973). "Die Leitsubstanzen der Haschisch-Suchhunde". Kriminalistik: Z Gesamte Kriminal Wiss Prax. 27: 385–389.

- ↑ Mediavilla, Vito; Simon Steinemann. "Essential oil of Cannabis sativa L. strains". International Hemp Association. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ↑ Singh G, Marimuthu P, de Heluani CS, Catalan CA (January 2006). "Antioxidant and biocidal activities of Carum nigrum (seed) essential oil, oleoresin, and their selected components". J. Agric. Food Chem. 54 (1): 174–81. doi:10.1021/jf0518610. PMID 16390196.

- ↑ Alma, M. Hakkı; Ertaş, Murat; Nitz, Siegfrie; Kollmannsberger, Hubert (May 2007). Lucia, Lucian A.; Hubbe, Martin A., eds. "Chemical composition and content of essential oil from the bud of cultivated Turkish clove" (PDF). BioResources. Raleigh, North Carolina, USA: North Carolina State University. 2 (2): 265–269. ISSN 1930-2126. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

The results showed that the essential oils mainly contained about [...] 3.56% β-Caryophyllene

- ↑ Wang G, Tian L, Aziz N, et al. (November 2008). "Terpene Biosynthesis in Glandular Trichomes of Hop". Plant Physiol. 148 (3): 1254–66. doi:10.1104/pp.108.125187. PMC 2577278. PMID 18775972.

- ↑ Bernotienë, Genovaitë; Nivinskienë, Ona; Butkienë, Rita; Mockutë, Danutë (2004). "Chemical composition of essential oils of hops (Humulus lupulus L.) growing wild in Auktaitija" (PDF). Chemija. 2. Vilnius, Lithuania: Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. 4: 31–36. ISSN 0235-7216. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ↑ Zheljazkov VD, Cantrell CL, Tekwani B, Khan SI (January 2008). "Content, composition, and bioactivity of the essential oils of three basil genotypes as a function of harvesting". J. Agric. Food Chem. 56 (2): 380–5. doi:10.1021/jf0725629. PMID 18095647.

- ↑ Silva, Maria Goretti de Vasconcelos; Matos, Francisco José de Abreu; Lopes, Paulo Roberto Oliveira; Silva, Fábio Oliveira; Holanda, Márcio Tavares (August 2, 2004). Cragg, Gordon M.; Bolzani, Vanderlan S.; Rao, G. S. R. Subba, eds. "Composition of essential oils from three Ocimum species obtained by steam and microwave distillation and supercritical CO2 extraction" (PDF). Arkivoc. ARKAT USA, Inc. 2004 (vi): 66–71. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0005.609. ISSN 1424-6376. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ↑ Harvala C, Menounos P, Argyriadou N (February 1987). "Essential Oil from Origanum dictamnus". Planta Med. 53 (1): 107–9. doi:10.1055/s-2006-962640. PMID 17268981.

- ↑ Calvo-Irabien, L. M.; Yam-Puc, J. A.; Dzib, G.; Escalante-Erosa, F.; Peña-Rodriguez, L. M. (July 2009). "Effect of Postharvest Drying on the Composition of Mexican Oregano (Lippia graveolens) Essential Oil". Journal of Herbs, Spices & Medicinal Plants. London, UK: Taylor & Francis. 15 (3): 281–287. doi:10.1080/10496470903379001. ISSN 1540-3580.

- ↑ Mockute, D; Bernotiene, G; Judzentiene, A (May 2001). "The essential oil of Origanum vulgare L. ssp. vulgare growing wild in vilnius district (Lithuania)". Phytochemistry. 57 (1): 65–9. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00474-x. PMID 11336262.

- ↑ Prashar, A.; Locke, I. C.; Evans, C. S. (2004). "Cytotoxicity of lavender oil and its major components to human skin cells". Cell Proliferation. 37 (3): 221–229. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2184.2004.00307.x. PMID 15144499.

- ↑ Umezu, Toyoshi; Nagano, Kimiyo; Ito, Hiroyasu; Kosakai, Kiyomi; Sakaniwa, Misao; Morita, Masatoshi (1 December 2006). "Anticonflict effects of lavender oil and identification of its active constituents". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 85 (4): 713–721. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2006.10.026. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ Jamshidi, R.; Afzali, Z.; Afzali, D. (February 2009). "Chemical Composition of Hydrodistillation Essential Oil of Rosemary in Different Origins in Iran and Comparison with Other Countries" (PDF). American-Eurasian Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences. Pakistan: IDOSI Publications. 5 (1): 78–81. ISSN 1990-4053. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ↑ Kaul PN, Bhattacharya AK, Rao BR, et al. (2003). "Volatile constituents of essential oils isolated from different parts of cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume)". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 83 (1): 53–55. doi:10.1002/jsfa.1277.

- ↑ Ahmed A, Choudhary MI, Farooq A, et al. (2000). "Essential oil constituents of the spice Cinnamomum tamala (Ham.) Nees & Eberm". Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 15 (6): 388–390. doi:10.1002/1099-1026(200011/12)15:6<388::AID-FFJ928>3.0.CO;2-F.

- ↑ Leandro, L. M.; Vargas Fde, S; Barbosa, P. C.; Neves, J. K.; Da Silva, J. A.; Da Veiga-Junior, V. F. (2012). "Chemistry and biological activities of terpenoids from copaiba (Copaifera spp.) oleoresins". Molecules. 17 (4): 3866–89. doi:10.3390/molecules17043866. PMID 22466849.

- ↑ Sousa, J. P.; Brancalion, A. P.; Souza, A. B.; Turatti, I. C.; Ambrósio, S. R.; Furtado, N. A.; Lopes, N. P.; Bastos, J. K. (Mar 2011). "Validation of a gas chromatographic method to quantify sesquiterpenes in copaiba oils". J Pharm Biomed Anal. 54 (4): 653–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2010.10.006. PMID 21095089.

- ↑ The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. "Revisions to FCC, First Supplement". Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ↑ Therapeutic Goods Administration. "Chemical substances" (PDF). Retrieved 29 June 2009.