Bering Strait crossing

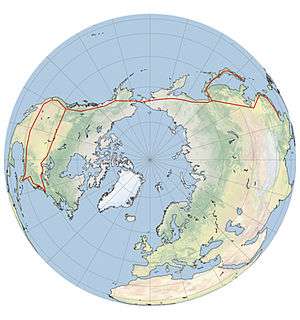

A Bering Strait crossing is a hypothetical bridge and/or tunnel spanning the relatively narrow and shallow Bering Strait between the Chukotka Peninsula in Russia and the Seward Peninsula in the US state of Alaska. The bridge/tunnel would provide a connection linking North America and Eurasia.

With the two Diomede Islands between the peninsulas, the Bering Strait could be spanned by a bridge/tunnel. There might be one long bridge, almost 40 kilometres (25 mi) long, connecting Alaska and the Diomede Islands, and a tunnel connecting the Diomede Islands and Russia. The earth bored from the tunnel could be used as landfill to connect the two islands.

There have been several proposals for a Bering Strait crossing made by various individuals and media outlets. The names used for them include "The Intercontinental Peace Bridge" and "Eurasia-America Transport Link".[1] Tunnel names have included "TKM-World Link" and "AmerAsian Peace Tunnel". In April 2007, Russian government officials told the press that the Russian government will back a US$65 billion plan by a consortium of companies to build a Bering Strait tunnel.[2]

History

19th century

The concept of an overland connection crossing the Bering Strait goes back before the 20th century. William Gilpin, first governor of the Colorado Territory, envisioned a vast "Cosmopolitan Railway" in 1890 linking the entire world through a series of railways.

Two years later, Joseph Strauss, who went on to design over 400 bridges, and then serve as the Project Engineer for the Golden Gate Bridge, put forward the first proposal for a Bering Strait railroad bridge in his senior thesis.[3] The project was presented to the government of the Russian Empire, but it was rejected.[4]

20th century

A syndicate of American railroad magnates proposed in 1904 (through a French spokesman) a Siberian-Alaskan railroad from Cape Prince of Wales in Alaska through a tunnel under the Bering Strait and across northeastern Siberia to Irkutsk via Cape Dezhnev, Verkhnekolymsk and Yakutsk. The proposal was for a 90-year lease, and exclusive mineral rights for 8 miles (13 km) each side of the right-of-way. It was debated by officials and finally turned down on March 20, 1907.[5]

Czar Nicholas II approved a tunnel (possibly the American proposal above) in 1905.[6] Its cost was estimated at $65 million[7] and $300 million including all the railroads.[6]

These hopes were dashed with the outbreak of World War I and the Russian Revolution.[8]

Interest was renewed during World War II with the completion in 1942-43 of the Alaska Highway linking the remote territory of Alaska with Canada and the continental United States. In 1942 the Foreign Policy Association envisioned the highway continuing to link with Nome near the Bering Strait, linked by motorway to the railhead at Irkutsk, using an alternative sea and air ferry service across the Bering Strait.[9]

In 1958 engineer T. Y. Lin suggested the construction of a bridge across the Bering Strait "to foster commerce and understanding between the people of the United States and the Soviet Union".[10] Ten years later he organized the Inter-Continental Peace Bridge, Inc., a non-profit institution organized to further this proposal.[10] At that time he made a feasibility study of a Bering Strait bridge and estimated the cost to be $1 billion for the 50-mile (80 km) span.[11] In 1994 he updated the cost to more than $4 billion. Like Gilpin, Lin envisioned the project as a symbol of international cooperation and unity, and dubbed the project the Intercontinental Peace Bridge.[12]

21st century

According to a report in the Beijing Times in May 2014, Chinese transportation experts are proposing building a roughly 10,000 kilometre (6,213 mi)-long high-speed rail line from Manchuria to the United States.[13] The project would include a tunnel under the Bering Strait and connect to the contiguous United States via Canada.

Technical concerns

Depth of water

The depth of the water is a minor problem, as the strait is no deeper than 55 meters (180 ft).[12] The tides and currents in the area are not severe.[10]

Weather-related challenges

Restrictions on construction work

The route is just south of the Arctic Circle, and the location has long, dark winters and extreme weather, including average winter lows of −20 °C (−4 °F) and possible lows approaching −50 °C (−58 °F). This would mean that construction work would likely be restricted to five months of the year.[12]

Exposed steel

The weather also poses challenges to exposed steel.[12] In Lin's design, concrete covers all structures, to simplify maintenance and to offer additional stiffening.[12]

Ice floes

Although there are no icebergs in the Bering Strait, ice floes up to 1.8 meters (6 ft) thick are in constant motion during certain seasons, which could produce forces of the order of 44 meganewtons (9,900,000 pounds-force; 4,500 tonnes-force) on a pier.[10]

Tundra in surrounding regions

Roads on either side of the strait would likely have to cross tundra, requiring either an unpaved road or some way to avoid the effects of permafrost.

Likely route and expenses

The bridge itself

The bridge would probably connect Wales in Alaska to a location south of Uelen. The bridge would also be divided by the Diomede Islands, which are at the middle of the Bering Strait. However, a tunnel would be necessary through the Diomede Islands, as Big Diomede Island is well over 1,000 feet high at its highest point.

In 1994, Lin estimated the cost of a bridge to be "a few billion" dollars.[12] The roads and railways on each side were estimated to cost $50 billion.[12] Lin contrasted this cost to petroleum resources "worth trillions".[12] Discovery Channel's Extreme Engineering estimates the cost of a highway, electrified double-track high-speed rail and pipelines, at $105 billion, five times the cost of the 50-kilometre (31 mi) Channel Tunnel.[14]

Connections to the rest of the world

This excludes the cost of new roads and railways to reach the bridge. Aside from the obvious technical challenges of building two 40-kilometre (25 mi) bridges or a more than 80-kilometre (50 mi) tunnel across the strait, another major challenge is that, as of 2017, there is nothing on either side of the Bering Strait to connect the bridge to.

Russian side

The Russian side of the Strait, in particular, is severely lacking in infrastructure. No railroads exist for over 3,200 kilometres (2,000 mi) in any direction from the strait.[15]

The nearest major connecting highway is the M56 Kolyma Highway, which is currently unpaved and around 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) from the stait.[16] However, by 2025, a road is planned to be built connecting Ola and Anadyr, which is only about 600 kilometres (370 mi) from the Strait.[17]

American side

On the American side, probably about 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) of highways or railways would have to be built around Norton Sound, through a pass along the Unalakleet River, and along the Yukon River to connect to Manley Hot Springs Road - in other words, a route similar to that of the Iditarod Trail Race. A project to connect Nome (100 miles (160 km) from the strait) to the rest of the continent by a paved highway (part of Alaska Route 2) has been proposed by the Alaskan state government, although the very high cost ($2.3 to $2.7 billion, about $5 million per mile, or $3 million per kilometer) has so far prevented construction.[18]

The Alaskan road network was expanded in 2016 to Tanana by building a 50 miles (80 km) fairly simple road. Further roads towards Nome are not planned as of 2016.

The TKM-World Link

The TKM-World Link (Russian: ТрансКонтинентальная магистраль, English: Transcontinental Railway) also called ICL-World Link (Intercontinental link) is a planned 6,000-kilometer link between Siberia and Alaska providing oil, natural gas, electricity, and railroad passengers to the United States from Russia. Proposed in 2007, the plan includes provisions to build a 103-kilometre (64 mi) tunnel under the Bering Strait which, if completed, would become the longest tunnel in the world.[19] The tunnel would be part of a railway joining Yakutsk, the capital of the Russian Yakutia republic, and Komsomolsk-on-Amur, in the Russian Far East, with the western coast of Alaska.[20] The Bering Strait tunnel was estimated to cost between $10 billion to $12 billion, while the entire project was estimated to cost $65 billion.[19]

In 2008, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin approved the plan to build a railroad to the Bering Strait area, as a part of the development plan to run until 2030. The more than 100-kilometre (60 mi) tunnel would run under the Bering Strait between Chukotka, in the Russian far east, and Alaska.[21] The cost estimate was US$66 billion.[22]

In late August 2011, at a conference in Yakutsk in eastern Russia, the plan was backed by some of President Dmitry Medvedev's top officials, including Aleksandr Levinthal, the deputy federal representative for the Russian Far East.[20] It would be a faster, safer, and cheaper way to move freight around the world than container ships, supporters of the idea believed.[20] They estimated it could carry about 3% of global freight and make about US$7 billion a year.[20] Shortly after, the Russian government approved the construction of the US$65 billion Siberia-Alaska rail and tunnel across the Bering Strait.[21]

Other observers doubt that this will be cheaper than container ships, bearing in mind that the cost for transport from China to Europe by railroad is higher than by container ship (except for expensive cargo where lead time is important).[23]

In 2013 the railway Amur Yakutsk Mainline connecting Yakutsk (2,800 km or 1,700 mi from the strait) with the main rail network was completed. However, this railway is meant for freight and is too curvy for high-speed passenger trains. Future projects include the Lena–Kamchatka Mainline and Kolyma–Anadyr highway. The Kolyma–Anadyr highway has started construction, but will be a narrow gravel road.

"China–Russia–Canada–America" railway

In 2014, reports emerged that China is considering construction of a "China–Russia–Canada–America" 350 km/h bullet train railroad that would include a 200-kilometre-long (120 mi) undersea tunnel crossing the Bering Strait and would allow passengers to travel between the United States and China in about two days.[24][25]

Although the press remain skeptical of the project, China's state-run China Daily claims that China possesses the necessary technology, which will be used to construct a tunnel underneath the Taiwan Strait.[26] It is unknown who is expected to pay for the construction, although China has in other projects offered to build and finance them, and expects the money back in the end through fees or rents. It is also unknown how many passengers would prefer a three-day train trip to a 12-hour direct flight, such as Los Angeles to Beijing.

Trans-Eurasian Belt Development

In 2015 it was reported another possible collaboration between China and Russia that will be part of the Trans-Eurasian Belt Development; a transportation corridor across Siberia that would also include a road bridge with gas and oil pipelines between the easternmost point of Siberia and the westernmost point of Alaska. It would link London and New York by rail and superhighway via Russia if it were to go ahead.[27]

China's Silk Road Economic Belt Initiative has similar plans so the project would work in parallel for both countries.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ A Transcontinental Eurasia-America Transport Link via the Bering Strait Archived 2007-11-14 at the Wayback Machine., at the 1st International Conference "Megaprojects of the Russian East"

- ↑ "Russia wants a rail link to North America," Der Spiegel, April 20, 2007

- ↑ Kevin Starr. Endangered Dreams: The Great Depression in California, 330. Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-19-510080-8

- ↑ An excerpt from memoirs of the Russian Empire Minister of Land Forces Aleksandr Rediger (in Russian)

- ↑ Theodore Shabad and Victor L. Mote: Gateway to Siberian Resources (The BAM) pp. 70-71 (Halstead Press/John Wiley, New York, 1977) ISBN 0-470-99040-6

- 1 2 "Czar Authorizes American Syndicate to Begin Work". The New York Times. August 2, 1906. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

The Czar of Russia has issued an order authorizing the American syndicate, represented by Baron Loicq de Lobel, to begin work on the TransSiberian-Alaska ...

- ↑ Burr, William H. (January 1907). "Around the World by Rail". Locomotive engineers journal. Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers. 41: 108–111.

- ↑ Halpin, Tony (April 20, 2007). "Russia plans $65bn tunnel to America". London: The Times. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

- ↑ Special to THE NEW YORK TIMES (July 20, 1942). "AIRWAY TO RUSSIA VIA ALASKA URGED; Foreign Policy Association Also Favors Northern Sea Route and Bering Link". The New York Times. p. 3. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- 1 2 3 4 Troitsky, M. S. (1994). "1.10.4 Bering Strait Bridge Project". Planning and design of bridges (illustrated ed.). John Wiley and Sons. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-0-471-02853-6.

- ↑ "Engineer feels Bering Strait Bridge Possible". The Bulletin. April 23, 1969. p. 12. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pope, Gregory (April 1994). "Last Great Engineering Challenge: Alaska-Siberia Bridge". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. 171 (4): 56–58. ISSN 0032-4558.

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan (May 9, 2014). "China may build an undersea train to America". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Discovery Channel's Extreme Engineering

- ↑ "Trip from Russia to USA may take one hour soon". 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ "Google Earth". earth.google.com. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ↑ "Project to build road from Kolyma to Anadyr drawn up". TASS (in Russian). 2012-06-23. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ↑ COCKERHAM, SEAN (January 27, 2010). "Nome road could cost $2.7 billion". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- 1 2 Humber, Yuriy; Bradley Cook (April 18, 2007). "Russia Plans World's Longest Tunnel, a Link to Alaska". Bloomberg. Bloomberg. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Report: Tunnel linking US to Russia gains support". msnbc.com. 20 August 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- 1 2 "Russia Green Lights $65 Billion Siberia-Alaska Rail and Tunnel to Bridge the Bering Strait!". 23 August 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ↑ Smith, Nicola; Hutchins, Chris (2008-03-30). "Bridgebuilding Vladimir Putin wants tunnel to US". The Times. London. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ Logistics concept for the Chinese growth market (Deutsche Bahn, March 2014)

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan (2014-05-09). "China may build an undersea train to America". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ↑ Politi, Daniel (2014-05-10). "Report: China Mulls Construction of a High Speed Train to the U.S." Slate.com. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ↑ "China mulls high-speed train to US: report". chinadaily.com.cn. 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ↑ "Russia unveils plans for high speed railway and superhighway to connect Europe and America". Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ↑ "Russian, China's trans-Asia programs complementary: railway chief". Retrieved 2015-08-02.

Further reading

- Oliver, James A. "The Bering Strait Crossing". Information Architects. ISBN 0-9546995-6-4.

- "Russians dream of tunnel to Alaska". BBC News. 2001-01-03. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- "Russia Considering Tunnel Between Asia and North America". VOA. 2007-04-19. Archived from the original on 2007-05-23. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- Oliver, James A.; Podderegin, Andrey; Mashin, Dmitiri (2007). ICL World Link: Intercontinental Eurasia-America Transport Corridor Via the Bering Strait. The Company of Writers. ISBN 0955663806.

External links

- Kremlin paves way for East to West rail link after 'approving' $99bn Bering Strait tunnel

- Discovery Channel's Extreme Engineering

- World Peace King Tunnel

- Trans-Global Highway

- The Bering Strait Crossing

- Alaska Canada Rail Link - Project Feasibility Study

- The Bridge Over the Bering Strait by James Cotter

- A Superhighway Across the Bering Strait, The Atlantic

- BART's Underwater Tunnel Withstands Test