Berenice Abbott

| Berenice Abbott | |

|---|---|

Abbott by Hank O'Neal in New York City, November 18, 1979 | |

| Born |

Bernice Abbott July 17, 1898 Springfield, Ohio, US |

| Died |

December 9, 1991 (aged 93) Monson, Maine, US |

| Resting place | New Blanchard Cemetery, Blanchard, Maine, U.S.[1] |

| Nationality | United States |

| Known for | Photography |

Berenice Abbott (July 17, 1898 – December 9, 1991),[2] née Bernice Alice Abbott, was an American photographer best known for her portraits of between-the-wars 20th century cultural figures, New York City photographs of architecture and urban design of the 1930s, and science interpretation in the 1940s to 1960s.

Early years

Abbott was born in Springfield, Ohio[3] and brought up there by her divorced mother, née Lillian Alice Bunn (m. Charles E. Abbott in Chillicothe OH, 1886).

She attended Ohio State University for two semesters, but left in early 1918 because her professor was dismissed because he was a German teaching an English class.[4] In Paris, she became an assistant to Man Ray, who wanted someone with no previous knowledge of photography.[5]

Trip to Europe, photography, and poetry

Her university studies included theater and sculpture.,[6] She spent two years studying sculpture in Paris and Berlin.[2] She studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris and the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin.[7] During this time, she adopted the French spelling of her first name, "Berenice," at the suggestion of Djuna Barnes.[8] In addition to her work in the visual arts, Abbott published poetry in the experimental literary journal transition.[9] Abbott first became involved with photography in 1923, when Man Ray hired her as a darkroom assistant at his portrait studio in Montparnasse. Later, she wrote: "I took to photography like a duck to water. I never wanted to do anything else." Ray was impressed by her darkroom work and allowed her to use his studio to take her own photographs.[10] In 1921 her first major works was in an exhibition in the Parisian gallery "Le Sacre du Printemps". In 1926, she exhibited her work in the gallery "Au Sacre du Printemps" and started her own studio on the rue du Bac. After a short time studying photography in Berlin, she returned to Paris in 1927 and started a second studio, on the rue Servandoni.[11]

Abbott's subjects were people in the artistic and literary worlds, including French nationals (Jean Cocteau), expatriates (James Joyce), and others just passing through the city. According to Sylvia Beach, "To be 'done' by Man Ray or Berenice Abbott meant you rated as somebody".[12] Abbott's work was exhibited with that of Man Ray, André Kertész, and others in Paris, in the "Salon de l'Escalier"[13] (more formally, the Premier Salon Indépendant de la Photographie), and on the staircase of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Her portraiture was unusual within exhibitions of modernist photography held in 1928–1929 in Brussels and Germany.[14]

In 1925, Man Ray introduced her to Eugène Atget's photographs. She became interested in Atget's work,[15] and managed to persuade him to sit for a portrait in 1927.[16] He died shortly thereafter. She acquired the prints and negatives remaining in Eugène Atget’s studio at his death in 1927.[17] While the government acquired much of Atget's archive — Atget had sold 2,621 negatives in 1920, and his friend and executor André Calmettes sold 2,000 more immediately after his death[18] — Abbott was able to buy the remainder in June, 1928, and quickly started work on its promotion. An early tangible result was the 1930 book Atget, photographe de Paris[19], in which she is described as photo editor. Due to a lack of funding, Abbott sold a one-half interest in the collection to Julien Levy for $1,000.[20] Abbott's work on Atget's behalf would continue until her sale of the archive to the Museum of Modern Art in 1968. In addition to her book The World of Atget (1964), she provided the photographs for A Vision of Paris (1963), published a portfolio, Twenty Photographs, and wrote essays.[21] Her sustained efforts helped Atget gain international recognition. Abbott's work is mostly known for her monochrome designs of New York City and it's beautiful architecture. She has three notable pictures one would be the ‘Under the El at the Battery’.[22] The other would be "Night View".[23] Lastly "Portrait Of James Joyce".[24] There are works of her work in the United States at the SFMOMA and the J. Paul Getty Museum.

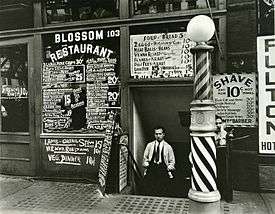

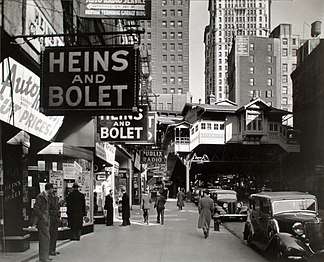

Changing New York

In early 1929, Abbott visited New York City, ostensibly to find an American publisher for Atget's photographs. After New York when she was doing portrait photography most of the time, she moved on to documentary photography.[25] Upon seeing the city again, Abbott recognized its photographic potential. She went back to Paris, closed up her studio, and returned to New York in September. She was a central figure that created bridge with photographic hubs in New York City.[26] Her first photographs of the city were taken with a hand-held Kurt-Bentzin camera, but soon she acquired a Century Universal camera which produced 8 x 10 inch negatives.[27] Using this large format camera, Abbott photographed New York City with the diligence and attention to detail she had so admired in Eugène Atget. Atget died in 1927 and she bought all his work which contained over 5000 negatives and glass slides from him and brought it to New York in 1929.[26] Her work has provided a historical chronicle of many now-destroyed buildings and neighborhoods of Manhattan. Her work appeared in an exhibition "Changing New York" at the Museum Of City in 1937.This was a book made to show the transformation of New York City. She focused more on the physical part of the transformation rather than the mental part of it, such as the change of neighborhoods and the replacement of skyscrapers to low rise buildings.[28]

Abbott worked on her New York project independently for six years, unable to get financial support from organizations (such as the Museum of the City of New York), foundations (such as the Guggenheim Foundation), or individuals. She supported herself with commercial work and teaching at the New School of Social Research beginning in 1933.[29]

In 1935, Abbott was hired by the Federal Art Project (FAP)[2] as a project supervisor for her "Changing New York" project. She continued to take the photographs of the city, but she had assistants to help her both in the field and in the office. This arrangement allowed Abbott to devote all her time to producing, printing, and exhibiting her photographs. By the time she resigned from the FAP in 1939, she had produced 305 photographs that were then deposited at the Museum of the City of New York.[27] Abbott's project was primarily a sociological study embedded within modernist aesthetic practices. She sought to create a broadly inclusive collection of photographs that together suggest a vital interaction between three aspects of urban life: the diverse people of the city; the places they live, work and play; and their daily activities. It was intended to empower people by making them realize that their environment was a consequence of their collective behavior (and vice versa). Moreover, she avoided the merely pretty in favor of what she described as "fantastic" contrasts between the old and the new, and chose her camera angles and lenses to create compositions that either stabilized a subject (if she approved of it), or destabilized it (if she scorned it).[30]

.jpg)

Abbott's ideas about New York were highly influenced by Lewis Mumford's historical writings from the early 1930s, which divided American history into a series of technological eras. Abbott, like Mumford, was particularly critical of America's "paleotechnic era", which, as he described it, emerged at end of the American Civil War, a development called by other historians the Second Industrial Revolution. Like Mumford, Abbott was hopeful that, through urban planning efforts (aided by her photographs), Americans would be able to wrest control of their cities from paleotechnic forces, and bring about what Mumford described as a more humane and human-scaled, "neotechnic era". Abbott's agreement with Mumford can be seen especially in the ways that she photographed buildings that had been constructed in the paleotechnic era—before the advent of urban planning. Most often, buildings from this era appear in Abbott's photographs in compositions that made them look downright menacing.[30]

In 1935, Abbott moved into a Greenwich Village loft with the art critic Elizabeth McCausland, with whom she lived until McCausland's death in 1965. McCausland was an ardent supporter of Abbott, writing several articles for the Springfield Daily Republican, as well as for Trend and New Masses (the latter under the pseudonym Elizabeth Noble). In addition, McCausland contributed the captions for the book of Abbott's photographs entitled Changing New York[31] which was published in 1939. In 1949, her photography book Greenwich Village Today and Yesterday was published by Harper & Brothers.

Ralph Steiner wrote in PM that Abbott's work was "the greatest collection of photographs of New York City ever made."[32]

Gallery

![]()

.jpg) Pike Street at Henry Street (1936)

Pike Street at Henry Street (1936).jpg) Automat in Manhattan (1936)

Automat in Manhattan (1936).jpg) Pennsylvania Station (1936)

Pennsylvania Station (1936).jpg) Detail of Manhattan Bridge (1936)

Detail of Manhattan Bridge (1936).jpg) Wanamaker's department store, Fourth Avenue and Ninth Street (1936)

Wanamaker's department store, Fourth Avenue and Ninth Street (1936) Financial District rooftops (1938)

Financial District rooftops (1938).jpg) Seventh Avenue, looking south from 35th Street (1935)

Seventh Avenue, looking south from 35th Street (1935).jpg) Flatiron Building (1938)

Flatiron Building (1938).jpg) House doorway on East 4th Street, Manhattan (1937)

House doorway on East 4th Street, Manhattan (1937).jpg) Hot dog stand, North Moore Street, Manhattan (1936)

Hot dog stand, North Moore Street, Manhattan (1936) Hardware store on the Bowery in Manhattan (1938)

Hardware store on the Bowery in Manhattan (1938) Radio Row at Cortlandt Street (1936)

Radio Row at Cortlandt Street (1936)

Beyond New York City

In 1934 Henry-Russell Hitchcock asked Abbott to photograph two subjects: antebellum architecture and the architecture of H. H. Richardson. Two decades later, Abbott and McCausland traveled US 1 from Florida to Maine, and Abbott photographed the small towns and growing automobile-related architecture.[2] The project resulted in more than 2,500 negatives.

Shortly after the trip, Abbott underwent a lung operation. She was told she should move from New York City due to air pollution. She bought a rundown home in Blanchard, Maine along the banks of the Piscataquis River for US$1,000. Later, she moved to nearby Monson, Maineand remained in Maine until her death in 1991. Most of her work is shown in the United States she has a couple in Europe but mostly in the U.S.

Abbott's work in continued in Maine. Her last book was A Portrait of Maine (1968).

Approach to photography

Abbott was part of the straight photography movement, which stressed the importance of photographs being unmanipulated in both subject matter and developing processes.[33] She also disliked the work of pictorialists who had gained much popularity during a substantial span of her own career and, therefore, left her work without support from this particular school of photographers. Most of Abbott's work was influenced by her childhood, she had an unhappy childhood and a lonely childhood. This gave her the determination to follow her dreams it made her a stronger person.[34]

Throughout her career, Abbott's photography was very much a display of the rise in development of technology and society. Her works documented and praised the New York landscape. This was all guided by her belief that a modern-day invention such as the camera deserved to document the 20th century.[35]

Scientific work

Abbott was not only a photographer, but also founded the corporation, "House of Photography," from 1947–1959, to develop, promote and sell some of her inventions. She stayed with scientific pictures for twenty years and she did it till she died.[25] She has a famous quote saying "the world is made my science".[36] Her works were displayed the rise of development of technology when she created scientific photographs her scientific photos became a hit within two weeks of her releasing them. These included a distortion enlarging easel, which created unusual effects on images developed in a darkroom, and the telescopic lighting pole, known today by many studio photographers as an "autopole," to which lights can be attached at any level. Owing to poor marketing, the House of Photography quickly lost money, and with the deaths of two designers, the company closed.

Abbott's style of straight photography helped her make important contributions to scientific photography. From 1958 to 1960, she produced a series of photographs for a high-school physics textbook, developed by the Physical Science Study Committee project based at MIT to improve secondary school physics teaching. Her work included images of wave patterns in water and stroboscopic images of moving objects, such as Bouncing ball in diminishing arcs, which was featured on the cover of the textbook.[37] She contributed to the understanding of physical laws and properties of solids and liquids though her studies of light and motion.[38] Between 1958 and 1961 she made a series of photographs for Educational Services Inc. was circulated by them and the Smithsonian Institution as an exhibition titled Image of Physics.[38] In 2012, some of her work from this era was displayed at the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[39]

Personal life

The film Berenice Abbott: A View of the 20th Century, which showed 200 of her black and white photographs, suggests that she was a “proud proto-feminist”; someone who was ahead of her time in feminist theory. Before the film was completed she questioned, "The world doesn't like independent women, why, I don't know, but I don't care." She identified publicly as a lesbian.[40]

She lived with her partner, art critic Elizabeth McCausland, for 30 years.[33]

Abbott's life and work are the subject of the 2017 novel The Realist: A Novel of Berenice Abbott, by Sarah Coleman.[41]

Notable photographs

- Under the El at the Battery, New York, 1936.

- Nightview, New York, 1932.

- James Joyce, Paris, 1929.

- Jay Street #115 New York, c. 1936.

- Automat, 977 Eighth Avenue, New York, February 10, 1936.

- Radio Row, Cortland Street, Manhattan, c. 1936.

- Night Scene, Manhattan, New York, 1935.

- Triboro Barber School, New York, 1935.

- The Hands of Jean Cocteau, 1927.

- West Street Row III, New York, 1938.

- Fifth Avenue Coach Company, New York, c. 1932.

- Edward Hopper in His Studio, 1948.

- Fifth Avenue Houses, Nos. 4,6,8, 1936.

- Flatiron Building, Broadway and 23rd Street, 1938.

- Trinity Church and Wall Street Towers, New York, 1934.

- Andre Beauclair, c. 1927.

- Man Ray, c. 1926.

Bibliography

Books of photographs by Abbott:

- 1939 Changing New York. New York: Dutton, 1939. With text by Elizabeth McCausland.[2]

- 1949 Greenwich Village: Yesterday and Today. New York: Harper, 1949. With text by Henry Wysham Lanier.

- 1968 A Portrait of Maine. New York: Macmillan, 1968. With text by Chenoweth Hall.

Other books by, or with major contributions from, Abbott:

- 1930 Atget, photographe de Paris. Paris: Henri Jonquières; New York: E. Weyhe, 1930. (As photograph editor.)[42]

- 1941 A Guide to Better Photography. New York: Crown, 1941[43] Revised edition: New Guide to Better Photography (New York: Crown, 1953)[44]

- 1948 The View Camera Made Simple. Chicago: Ziff-Davis, 1948[45]

- 1956 Twenty Photographs by Eugène Atget 1856–1927 (portfolio of silver prints by Abbott from original Atget negatives in her possession)[46]

- 1963 A Vision of Paris: The Photographs of Eugène Atget, the Words of Marcel Proust. New York: Macmillan, 1963. Edited by Arthur D. Trottenberg[47]

- 1964 The World of Atget. New York: Horizon, 1964.[48] (And later editions.)

- 1964 Magnet. Cleveland: World, 1964. With text by Evans G. Valens.[49]

- 1965 Motion. London: Longman Young, 1965. With text by Evans G. Valens[50]

- 1968 A Portrait of Maine. NY: Macmillan, 1968. With text by Chenoweth Hall[51]

- 1969 The Attractive Universe: Gravity and the Shape of Space. Cleveland: World, 1969. With text by Evans G. Valens[52]

- 2008 Berenice Abbott. Germany/New York: Steidl, 2008. 2v. Edited by Hank O'Neal and Ron Kurtz.[53] ISBN 3-86521-592-0

- 2010 Berenice Abbott". London: Thames & Hudson, 2010,[54] Introduction by Hank O'Neal

- 2012 Berenice Abbott: Documenting Science. Göttingen: Steidl, 2012.[55] Edited by Ron Kurtz, with introduction by Julia Van Haaften.

- 2014 The Unknown Berenice Abbott. Göttingen: Steidl, 2014. 5v. Edited by Ron Kurtz and Hank O'Neal[56]

- 2015 Berenice Abbott: Paris Portraits. Göttingen, Germany: Steidl; New York: Commerce Graphics, 2016. Edited by Hank O'Neal[57]

Anthologies of and/or about Abbott's works:

- 1970 Berenice Abbott: Photographs. New York: Horizon, 1970; reprinted, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990[58]

- 1982 O'Neal, Hank. Berenice Abbott: American Photographer. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982.[59] British title: Berenice Abbott: Sixty Years of Photography. London: Thames & Hudson, 1982[60]

- 1986 Berenice Abbott, fotografie / Berenice Abbott: Photographs. Venice: Ikona, 1986[61]

- 1989 Van Haaften, Julia, ed. Berenice Abbott, Photographer: A Modern Vision. New York: New York Public Library, 1989. [Winner, American Association of Museums’ exhibition catalog design award][62] ISBN 0-87104-420-X

- 2009 Shimizu, Meredith Ann TeGrotenhuis. "Photography in Urban Disclosure: Berenice Abbott's Changing New York and the 1930s," Ph.D. dissertation, Northwestern University, 2009[63]

- 2012 Morel, Gaëlle. Berenice Abbott. Paris: Éditions Hazan, 2012[64]

- 2015 Berenice Abbott. Aperture Masters of Photography 9, by Julia Van Haaften. New York: Aperture, 1988; trilingual edition, 1997;[65] completely revised edition, with new photos and text, 2015.[66] [Chinese translation 2015[67]

Solo exhibitions

- Weyhe Gallery, New York, NY, November 1930[68]

- Photographs by Berenice Abbott at Julien Levy Gallery, New York, NY, September 26 – October 15, 1932

- New York Photographs by Berenice Abbott at Museum of the City of New York, New York, NY, October 1934 – January 1935

- New York Photographs by Berenice Abbott at Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, MA, March 1935

- New York Photographs by Berenice Abbott at Jerome Stavola Gallery, Hartford, CT, April 1935

- New York Photographs by Berenice Abbott at Fine Arts Guild, Cambridge, MA, April 10–15, 1935

- Changing New York, Washington Circuit, Federal Art Project, traveling exhibition, 1936

- Changing New York at Museum of the City of New York, New York, NY, October 20, 1937 – January 3, 1938

- Changing New York at Teachers College Library, New York, NY, November 1937

- Solo exhibition at Hudson D. Walker Gallery, New York, NY, April 1938

- Changing New York at New York State Museum, Albany, NY, July 1938

- Changing New York at Federal Art Gallery, New York, NY, April 11–22, 1939

- Solo exhibition at Architectural League, New York, NY, April 1939

- Changing New York at Lawrenceville School, Lawrence Township, NJ, May 1939

- Changing New York at Photo League Gallery, New York, NY, July 1939

- Changing New York at New York State Employment Service, New York, NY, November – December 1939

- Changing New York at Walton High School, New York, NY, December 1939

- Photographs of New York by Berenice Abbott at The Cooper Union Library, New York, NY, November – December 1940

- Berenice Abbott, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, December 1970 – February 1971

- Berenice Abbott: The Red River Photographs at Hudson D. Walker Gallery, Provincetown, Massachusetts, August–September 1979.[69]

- Berenice Abbott, Photographer: A Modern Vision, The New York Public Library, New York NY, October 1989 – January 1990 (Traveled to Metropolitan Museum of Photography [Tokyo, Japan], Toledo [Ohio] Museum of Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art [Washington DC], and Portland [ME] Museum of Art, 1990–1992)

- Documenting New York: Photographs by Berenice Abbott, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas,1992

- Berenice Abbott: Portraits, New York Views, and Science Photographs from the Permanent Collection, International Center of Photography, New York, NY, 1996

- Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D.C.,1935–1939, 1998–99

- Berenice Abbott: Science Photographs, The New York Public Library, New York NY, October 1999 – January 2000

- Berenice Abbott: All About Abbott, Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, NY, September–November 2006

- Making Science Visible: The Photography of Berenice Abbott, The Fralin Museum of Art, Virginia, 2012

- Berenice Abbott (1898–1991), Photographs, Jeu de Paume, Paris, France, February–April 2012

- Berenice Abbott: Photography and Science: An Essential Unity, MIT Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, May–December 2012

- Berenice Abbott, Beetles & Huxley Gallery, London, England, October–November 2015

- Berenice Abbott – Photographs, Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, Germany, January–March 2016

- Berenice Abbott: The 20s and the 30s, International Center of Photography, New York City, November 22, 1981 – January 10, 1982

- Berenice Abbott: Vintage Photographs of New York from the 1930s,Lee Gallery, Winchester, MA, September 1999

- Berenice Abbott: The Red River Photographs, Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown, MA, August 1979

Collections

Abbott's work is held in the following permanent collections:

References

- ↑ Donald V. Brown, Christine Brown (comp.). Blanchard Cemetery, Abbot, Piscataquis, Maine, 1829 – 1990.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Abbott, Berenice". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-Ak – Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ↑ "Abbott, Berenice". Who Was Who in America, with World Notables, v. 10: 1989–1993. New Providence, NJ: Marquis Who's Who. 1993. p. 1. ISBN 0837902207.

- ↑ Yochelson, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ "Berenice Abbott". Biography. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ Sculpture, Ray, Hartmann: Julia Van Haaften, "Portraits", Berenice Abbott, Photographer: A Modern Vision (New York: New York Public Library, 1989), p. 11.

- ↑ Marter, Joan M. (2011). The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, Volume I. Oxford University Press. pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Herring, Phillip (1995). Djuna: The Life and Work of Djuna Barnes. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-017842-2.

- ↑ Benstock, Shari (1986). Women of the Left Bank: Paris, 1900–1940. Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-79040-6.

- ↑ Yochelson, p. 10. Abbott quotation: Abbott, untitled text dated December 1975, Berenice Abbott, Photographer: A Modern Vision, p. 8.

- ↑ Solo exhibition, studios: Van Haaften, "Portraits", Berenice Abbott, Photographer, p. 11.

- ↑ Beach quotation: Van Haaften, "Portraits", Berenice Abbott, Photographer, p. 11.

- ↑ http://img-3.journaldesfemmes.com/_AlerDfqgitR9wJ3lZ_WLBXbL2M=/1240x/smart/0339f058aacc4f10acbdc645ec91e67a/ccmcms-jdf/1293890.jpg

- ↑ Salon de l'Escalier, Belgian and German exhibitions: Van Haaften, "Portraits", Berenice Abbott, Photographer, p. 11.

- ↑ "Berenice Abbott - Bio". www.phillipscollection.org.

- ↑ O'Neal, Hank (2010). Berenice Abbott. New York, N.Y.: Thames & Hudson. pp. [p. 3]. ISBN 9780500411001.

- ↑ Lee., Morgan, Ann (2007). The Oxford dictionary of American art and artists. Oxford University Press. (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199891504. OCLC 181102756.

- ↑ Harris, David (2000) Eugène Atget: Unknown Paris. New York: New Press. ISBN 1-56584-854-3. pp. 13, 15.

- ↑ Mac-Orlan, Pierre (1930). Atget: Photographe de Paris. New York, N. Y.: E. Weyhe.

- ↑ O'Neal, Hank (2010). Berenice Abbott. New York, N. Y.: Thames & Hudson. pp. [p. 5]. ISBN 9780500411001.

- ↑ Harris, David (2000) Eugène Atget: Unknown Paris. New York: New Press. ISBN 1-56584-854-3. pp. 8, 188.

- ↑ "Under the El at the Battery, New York sold by Phillips, New York, on Friday, October 08, 2010". www.artvalue.com. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ "New York City At Night, 76 Years Ago". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ "Gallerist Sean Kelly donates his James Joyce collection to The Morgan Library and Museum in New York". www.theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- 1 2 "Berenice Abbott - Bio". www.phillipscollection.org. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 "Berenice Abbott | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- 1 2 Yochelson, introduction.

- ↑ "Berenice Abbott - Bio". www.phillipscollection.org. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ O’Neal, Hank and Berenice Abbott. Berenice Abbott: American Photographer. Introduction by John Canaday. New York: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1982.

- 1 2 Barr, Peter (1997) Becoming Documentary: Berenice Abbott's Photographs 1925–1939. Ph.D. dissertation. Boston University.

- ↑ McCausland, Elizabeth (1939). Changing New York. New York, N.Y.: E. P. Dutton & Company, Inc.

- ↑ Current Biography, 1942, 1.

- 1 2 Geyer, Andrea. "Revolt, They Said". www.andreageyer.info. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- ↑ "Berenice Abbott | International Photography Hall of Fame". International Photography Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ Yochelson, Berenice Abbott.

- ↑ O'Hagan, Sean (2015-03-10). "Berenice Abbott: the photography trailblazer who had supersight". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ↑ Crisis in US Science Education? Better Call in Avant-Garde Photographer Berenice Abbott Forbes

- 1 2 Gaze, Delia (1997). Dictionary of Women Artists, Volume I. Chicago, Illinois, USA: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 1-884964-21-4.

- ↑ "MIT Museum: Exhibitions – Berenice Abbott: Photography and Science: An Essential Unity". Web.mit.edu. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ↑ "An American from Paris". Vanity Fair. February 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ↑ Zoffness, Courtney (20 March 2018). "Art Lives: Sarah Coleman's "The Realist: A Novel of Berenice Abbott"". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ↑ Atget, Eugène; MacOrlan, Pierre; Abbott, Berenice; Jonquières, Henri; Henri Jonquières et cie; Marcel Seheur (Firm); Vigier et Brunissen (April 6, 2018). "Atget: photographe de Paris". Henri Jonquières, éditeur – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 2018). "A guide to better photography". Crown Publishers – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 2018). "New guide to better photography". Crown – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 2018). "The view camera made simple". Ziff-Davis Pub. Co. – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Atget, Eugène (April 6, 2018). "20 photographs". Abbott – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Atget, Eugène; TROTTENBERG, Arthur D; Proust, Marcel (April 6, 1963). "A Vision of Paris. The photographs of Eugène Atget. The words of Marcel Proust (reprinted from "Remembrance of Things Past"). Edited, with an introduction, by Arthur D. Trottenberg, etc. [With portraits of Atget and Proust.]". New York; Lausanne printed – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Atget, Eugène; Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 1964). "The world of Atget". Horizon Press – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Valens, Evans G; Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 1964). "Magnet". World Pub. Co. – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 1965). "Motion". World Publishing Co. – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice; Hall, Chenoweth (April 6, 1968). "A portrait of Maine". MacMillan ; Collier-Macmillan – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Valens, Evans G; Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 1969). "The attractive universe: gravity and the shape of space". World Pub. Co. – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice; Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 2018). "Berenice Abbott". Steidl – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice; O'Neal, Hank (April 6, 2018). "Berenice Abbott". Thames & Hudson – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice; Kurtz, Ron; Van Haaften, Julia; Durant, John (April 6, 2018). "Documenting science". Steidl – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice; Kurtz, Ron; O'Neal, Hank (April 6, 2018). "The unknown Abbott" – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice; Kurtz, Ron; O'Neal, Hank (April 6, 2018). "Berenice Abbott Paris Portraits 1925-1930". Steidl / Commerce Graphics – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 1990). "Berenice Abbott photographs". Smithsonian Institution Press – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ O'Neal, Hank; Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 1982). "Berenice Abbott, American photographer". McGraw-Hill – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ O'Neal, Hank; Abbott, Berenice; Canaday, John (April 6, 1982). "Berenice Abbott 60 years of photography". Thames and Hudson – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice; Scuola grande di San Giovanni Evangelista (Venice, Italy); Ikona Gallery (April 6, 1986). "Berenice Abbott, fotografie: Scuola grande San Giovanni Evangelista, 26 giugno-27 luglio 1986". Ikona Gallery – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice; Van Haaften, Julia (April 6, 1989). Berenice Abbott, photographer: a modern vision : a selection of photographs and essays. New York Public Library – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/880967643

- ↑ Morel, Gaëlle (April 6, 2018). "Berenice Abbott". Éditions Hazan – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Abbott, Berenice; Van Haaften, Julia (April 6, 1997). "Berenice Abbott". Könemann – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ Van Haaften, Julia; Abbott, Berenice (April 6, 2018). "Berenice Abbott" – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ 哈弗腾; 唐小佳 (April 6, 2018). "光圈世界摄影大师 = Aperture masters of photography". 中国摄影出版社 – via Open WorldCat.

- ↑ This list of exhibitions comes from Meredith TeGrotenhuis Shimizu's dissertation, "Photography and Urban Discourse: Berenice Abbott's Changing New York and the 1930s," 2008

- ↑ Artforum, Summer 1979

- ↑ Berenice Abbott papers at Manuscripts and Archives Division at the New York Public Library

- ↑ https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/archivalcollections/pdf/abbottb.pdf

- ↑ "Berenice Abbott: Changing New York" New York Public Library

- ↑ "Berenice Abbott" Museum of the City of New York

- ↑ "Berenice Abbott" The Jewish Museum (New York)

- ↑ "Berenice Abbott" Smithsonian American Art Museum

- ↑ "Berenice Abbott (1898–1991)" The Phillips Collection

- ↑ New Mexico Museum of Art

- ↑ "Works by Berenice Abbott at the Minneapolis Museum of Art". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

Cited sources

- Bonnie Yochelson (1997). Berenice Abbott: Changing New York. New York: New Press. ISBN 1565845560.

Further reading

- Bakewell, Joan; Rodger, Liam (2011). "Abbott, Berenice". Chambers Biographical Dictionary. 9th. Retrieved 15 Feb 2018.

- Broe, Mary Lynn (1993). Women's Writing in Exile. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807842515.

- Butet-Roch, Laurence, "Berenice Abbott: Writing Her Own History," The New York Times, May 6, 2015

- Documentary Film: Berenice Abbott: A View of the Twentieth Century (1992)

- Hillstrom, L. C., & Hillstrom, K. (1999). Contemporary women artists. Detroit: St. James Press.

- Kauffman, Bette (1999). "Abbott, Berenice". In Commire, Anne. Women in World History: A biographical encyclopedia. 1. Waterford, CT: Yorkin Publications, Gale Group. pp. 11–17. ISBN 0787640808.

- Noyes Platt, Susan (2004). "Berenice Abbott". In Susan Ware. Notable American Women: A biographical dictionary, completing the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 067401488X.

- Stern, Keith (2009), "Abbott, Bernice", Queers in History, BenBella Books, Inc.; Dallas, Texas, ISBN 978-1-933771-87-8

- Wedge, Eleanor F. (2000). "Abbott, Berenice (1898-1991), photographer". American National Biography.

- Van Haaften, Julia (2018). Berenice Abbott: A Life in Photography, W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393292789, ISBN 978-0393292787.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Berenice Abbott |

- Corinne, Tee A. "Berenice Abbott" (GLBTQ: An encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, transgender and queer culture.)

- Teicher, Jessica E. "Inspired by Berenice Abbott"

- "Berenice Abbott's Photographic Prints"(Commerce Graphics Ltd, Inc.)

- Berenice Abbott (The Museum of Modern Art)

- Get the Picture: Berenice Abbott (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

- Berenice Abbott (Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions)