Kingdom of Benin

| Kingdom of Benin Edo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1180–1897 | |||||||||

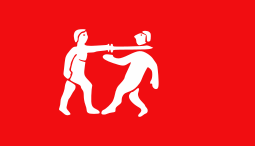

Flag | |||||||||

The extent of Benin in 1625 | |||||||||

| Capital |

Edo (now Benin City) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Edo | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King/Emperor (Oba) | |||||||||

• 1180–1246 | Eweka I [1] | ||||||||

• 1440–1473 | Ewuare (1440–1473) | ||||||||

• | Ovonramwen (exile 1897) | ||||||||

• 1978–2016 | Erediauwa I (post-imperial) | ||||||||

• 2016- | Ewuare II (post-imperial) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1180 | ||||||||

• Annexed by the United Kingdom | 1897 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1625 | 90,000 km2 (35,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as the Benin Kingdom, was a pre-colonial kingdom in what is now southern Nigeria. Its capital was Edo, now known as Benin City in Edo state. It should not be confused with the modern-day Republic of Benin, formerly the Republic of Dahomey. The Benin Kingdom was "one of the oldest and most highly developed states in the coastal hinterland of West Africa, dating perhaps to the eleventh century CE",[2] until it was annexed by the British Empire in 1897.

History

The original people and founders of the Benin Kingdom, the Edo people, were initially ruled by the Ogiso (Kings of the Sky) who called their land Igodomigodo. The first Ogiso (Ogiso Igodo), wielded much influence and gained popularity as a good ruler. He died after a long reign and was succeeded by Ere, his eldest son. In the 12th century, a great palace intrigue erupted and crown prince Ekaladerhan, the only son of the last Ogiso was sentenced to death as a result of the first Queen (who was barren) deliberately changing an oracle message to the Ogiso. In carrying out the order of the palace, the palace messengers had mercy and set the prince free at Ughoton near Benin. When his father the Ogiso died, the Ogiso dynasty ended. The people and royal kingmakers preferred their king's son as natural next in line to rule.

The exiled Prince Ekaladerhan had changed his name to Izoduwa meaning 'I have chosen the part of prosperity' and found his way to Ile-Ife. It was during this period of confusion the elders led by Oliha mounted a search for the banished Prince Ekaladerhan whom the Ife people will now called Oduduwa. Oduduwa, who could not return due to age, granted them Oranmiyan, his son, to rule over them. Oranmiyan was resisted by Ogiamien Irebor, one of the palace chiefs and took up his abode in the palace built for him at Usama by the elders (now a coronation shrine). Soon after his arrival he married a beautiful lady, Erinmwinde, daughter of Ogie-Egor, the ninth Enogie (Duke) of Egor, by whom he had a son. After some years residence here he called a meeting of the people and renounced his office, remarking that the country was a land of vexation, Ile-Ibinu Yoruba words (by which name the country was afterward known) and that only a child born, trained and educated in the arts and mysteries of the land could reign over the people. He caused his son born to him by Erinmwinde to be made King in his place, and returned to Yoruba land Ile-Ife. His son whom he left behind was deaf and dumb, and the elders recoursed to Oranmiyan who gave them charmed seeds "omo ayo" to play with which will make him to talk. The little Oranmiyan played with the seeds with his peers at Egor his mother’s hometown. While playing with the seeds he announced "Owomika" meaning 'my hands catch it' in yoruba but corrupted to 'Eweka' by the Edos. This is why every Oba of Benin must stay seven days in Usama and announce his name at Egor. Eweka thus started the Oba dynasty. Oranmiyan was also the founder of Oyo Empire where he ruled supreme as the first Aalafin of Oyo and proceeded to ile ife to become the 6th Ooni of ife while his descendants rules in Ile Ife, Oyo and Benin.

By the 15th century, Benin had expanded into a thriving city-state. The twelfth Oba in line, Oba Ewuare the Great (1440–1473) would expand the city-state's territories to surrounding regions.

It was not until the 15th century during the reign of Oba Ewuare the Great that the kingdom's administrative centre, the city Ubinu, began to be known as Benin City by the Portuguese, later be adopted by the locals as well. Before then, due to the pronounced ethnic diversity at the kingdom's headquarters during the 15th century from the successes of Oba Ewuare, the earlier name ('Ubinu') by a tribe of the Edos was colloquially spoken as "Bini" by the mix of Itsekhiri, Esan, Igbo, Ijaw Edo, Urhobo living together in the royal administrative centre of the kingdom. The Portuguese would write this down as Benin City. Though, farther Edo clans, such as the Itsekiris and the Urhobos still referred to the city as Ubini up till the late 19th century, as evidence implies.

Aside from Benin City, the system of rule of the Oba in his kingdom, even through the golden age of the kingdom, was still loosely based after the Ogiso dynasty, which was military and royal protection in exchange of use of resources and implementation of taxes paid to the royal administrative centre. Language and culture was not enforced but remained heterogeneous and localized according to each group within the kingdom, though a local "Enogie" (duke) was often appointed by the Oba for specified ethnic areas.

Oral tradition

The original name of the Benin Kingdom, at its creation some time in the first millennium CE, was Igodomigodo, as its inhabitants called it. Their ruler was called Ogiso.[3]

Nearly 36 known Ogiso are accounted for as rulers of this initial incarnation of the state. According to Edo oral tradition, during the reign of the last Ogiso, his son and heir apparent, Ekaladerhan, was sentenced to death because one of the Queens deliberately changed an oracle message to the Ogiso. In carrying out the order of the palace, the palace messengers set him free recognizing his innocence.

On the death of the last Ogiso, a group of Benin Chiefs led by Chief Oliha mounted a search for their banished Prince Ekaladerhan who the Ife people will now call Oduduwa to Ile-Ife, pleaded for Oduduwa return(The Ooni) but were granted one of his sons as King in Igodomigodo (later known as Benin City).

Centuries later, in 1440, Oba Ewuare, also known as Ewuare the Great, came to power and expanded the borders of the former city-state. It was only at this time that the administrative centre of the kingdom began to be referred to as Ubinu after the Yoruba word and corrupted to Bini by the Itsekhiri, Edo, and Urhobo living together in the royal administrative centre of the kingdom. The Portuguese who arrived in an expedition led by Joao Afonso de Aveiro in 1485 would refer to it as Benin and the centre would become known as Benin City.

The Kingdom of Benin, eventually gained political strength and ascendancy over much of what is now mid-western Nigeria. Nowadays, scientists have discovered that the Edo people did have a writing system, their art work which had let the scientists discover their true history. Including the armor, magnificent drawing skills.

Golden Age

The Oba had become the mount of power within the region. Oba Ewuare, the first Golden Age Oba, is credited with turning Benin City into a city state from a military fortress built by the Ogisos, protected by moats and walls. It was from this bastion that he launched his military campaigns and began the expansion of the kingdom from the Edo-speaking heartlands.

A series of walls marked the incremental growth of the sacred city from 850 AD until its decline in the 16th century. To enclose his palace he commanded the building of Benin's inner wall, an 11-kilometre-long (7 mi) earthen rampart girded by a moat 6 m (20 ft) deep. This was excavated in the early 1960s by Graham Connah. Connah estimated that its construction, if spread out over five dry seasons, would have required a workforce of 1,000 laborers working ten hours a day seven days a week. Ewuare also added great thoroughfares and erected nine fortified gateways.

Excavations also uncovered a rural network of earthen walls 6,000 to 13,000 km (4,000 to 8,000 mi) long that would have taken an estimated 150 million man-hours to build and must have taken hundreds of years to build. These were apparently raised to mark out territories for towns and cities. 13 years after Ewuare's death tales of Benin's splendors, more Portuguese traders were lured to the city gates.[4]

At its height, Benin dominated trade along the entire coastline from the Western Niger Delta, through Lagos to modern-day Ghana.[5] It was for this reason that this coastline was named the Bight of Benin. The present-day Republic of Benin, formerly Dahomey, decided to choose the name of this bight as the name of its country. Benin ruled over the tribes of the Niger Delta including the Western Igbo, Ijaw, Itshekiri, and Urhobo amongst others. It also held sway over the Eastern Yoruba tribes of Ondo, Ekiti, Mahin/Ugbo, and Ijebu.[6] It also established the first colony of Lagos hundreds of years before the British took over in 1851.[7]

The state developed an advanced artistic culture, especially in its famous artifacts of bronze, iron and ivory. These include bronze wall plaques and life-sized bronze heads depicting the Obas of Benin. The most well-known artifact is based on Queen Idia, now best known as the FESTAC Mask after its use in 1977 in the logo of the Nigeria-financed and hosted Second Festival of Black & African Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77).

European contact

The first European travelers to reach Benin were Portuguese explorers starting with Joao Afonso de Aveiro in about 1485. A strong mercantile relationship developed, with the Edo trading slaves and tropical products such as ivory, pepper and palm oil with for European goods such as Manilla (money) and guns. In the early 16th century, the Oba sent an ambassador to Lisbon, and the king of Portugal sent Christian missionaries to Benin City. Some residents of Benin City could still speak a pidgin Portuguese in the late 19th century.

The first English expedition to Benin was in 1553, and significant trading developed between England and Benin based on the export of ivory, palm oil, pepper, and slaves. Visitors in the 16th and 17th centuries brought back to Europe tales of "the Great Benin", a fabulous city of noble buildings, ruled over by a powerful king. However, the Oba began to suspect Britain of larger colonial designs and ceased communications with the British until the British Expedition in 1896-97 when British troops captured, burned, and looted Benin City as part of a punitive mission, which brought the kingdom to an end.[8]

A 17th-century Dutch engraving from Olfert Dapper's Nauwkeurige Beschrijvinge der Afrikaansche Gewesten, published in Amsterdam in 1668 says:

The king's palace or court is a square, and is as large as the town of Haarlem and entirely surrounded by a special wall, like that which encircles the town. It is divided into many magnificent palaces, houses, and apartments of the courtiers, and comprises beautiful and long square galleries, about as large as the Exchange at Amsterdam, but one larger than another, resting on wooden pillars, from top to bottom covered with cast copper, on which are engraved the pictures of their war exploits and battles...

Another Dutch traveler was David van Nyendael, who in 1699 wrote an eye-witness account.

Military

Military operations relied on a well trained disciplined force.[9] At the head of the host stood the Oba of Benin. The monarch of the realm served as supreme military commander. Beneath him were subordinate generalissimos, the Ezomo, the Iyase, and others who supervised a Metropolitan Regiment based in the capital, and a Royal Regiment made up of hand-picked warriors that also served as bodyguards. Benin's Queen Mother also retained her own regiment, the "Queen's Own". The Metropolitan and Royal regiments were relatively stable semi-permanent or permanent formations. The Village Regiments provided the bulk of the fighting force and were mobilized as needed, sending contingents of warriors upon the command of the king and his generals. Formations were broken down into sub-units under designated commanders. Foreign observers often commented favorably on Benin's discipline and organization as "better disciplined than any other Guinea nation", contrasting them with the slacker troops from the Gold Coast.[10]

Until the introduction of guns in the 15th century, traditional weapons like the spear, short sword, and bow held sway. Efforts were made to reorganize a local guild of blacksmiths in the 18th century to manufacture light firearms, but dependence on imports was still heavy. Before the coming of the gun, guilds of blacksmiths were charged with war production—particularly swords and iron spearheads.[9]

Olfert Dapper, Nauwkeurige Beschrijvinge der Afrikaansche Gewesten (Description of Africa), 1668.

Benin's tactics were well organized, with preliminary plans weighed by the Oba and his sub-commanders. Logistics were organized to support missions from the usual porter forces, water transport via canoe, and requisitioning from localities the army passed through. Movement of troops via canoes was critically important in the lagoons, creeks and rivers of the Niger Delta, a key area of Benin's domination. Tactics in the field seem to have evolved over time. While the head-on clash was well known, documentation from the 18th century shows greater emphasis on avoiding continuous battle lines, and more effort to encircle an enemy (ifianyako).[9]

Fortifications were important in the region and numerous military campaigns fought by Benin's soldiers revolved around sieges. As noted above, Benin's military earthworks are the largest of such structures in the world, and Benin's rivals also built extensively. Barring a successful assault, most sieges were resolved by a strategy of attrition, slowly cutting off and starving out the enemy fortification until it capitulated. On occasion however, European mercenaries were called on to aid with these sieges. In 1603–04 for example, European cannon helped batter and destroy the gates of a town near present-day Lagos, allowing 10,000 warriors of Benin to enter and conquer it. As payment the Europeans received items, such as palm oil and bundles of pepper.[11] The example of Benin shows the power of indigenous military systems, but also the role outside influences and new technologies brought to bear. This is a normal pattern among many nations and was to be reflected across Africa as the 19th century dawned.

Decline

Britain seeks control over trade

Benin began to decline after 1700. Benin's power and the wealth was continuously flourishing in the 19th century with the development of the trade in palm oil, textiles, ivory, slaves, and other resources. To preserve the kingdom's independence, bit by bit the Oba banned the export of goods from Benin, until the trade was exclusively in palm oil.

By the last half of the 19th century Great Britain had come to want a closer relationship with the Kingdom of Benin; for British officials were increasingly interested in controlling trade in the area and in accessing the kingdom's rubber resources to support their own growing tire market.

Several attempts were made to achieve this end beginning with the official visit of Richard Francis Burton in 1862 when he was consul at Fernando Pó. Following that came attempts to establish a treaty between Benin and the United Kingdom by Hewtt, Blair and Annesley in 1884, 1885 and 1886 respectively. However, these efforts did not yield any results. The kingdom resisted becoming a British protectorate throughout the 1880s, but the British remained persistent. Progress was made finally in 1892 during the visit of Vice-Consul Henry Galway. This mission was the first official visit after Burton's. Moreover, it would also set in motion the events to come that would lead to Oba Ovonramwen's demise.

The Galway Treaty of 1892

The Galway treaty allegedly signed by the king put the Kingdom of Benin under the authority of the British as a protectorate and abolished the slave trade and human sacrifice.[12] Despite the stories later told by Galway, there is today still some controversy on a number of points—most of all as to whether the Oba actually agreed to the terms of the treaty as Galway claimed. At the time of his visit to Benin the Oba could not welcome Galway or any other foreigners due to the observance of the traditional Igue festival which prohibited the presence of any non-native persons during the sacred season. Also, even though Gallwey claimed the King (Oba) and his chiefs were willing to sign the treaty, it was common knowledge that Oba Ovonramwen did not sign one-sided treaties. The treaty reads "Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, Empress of India in compliance with the request of [the] King of Benin, hereby extend to him and the territory under his authority and jurisdiction, Her gracious favour and protection" (Article 1). The Treaty also states "The King of Benin agrees and promises to refrain from entering into any correspondence, Agreement or Treaty with any foreign nation or power except with the knowledge of her Britannic Majesty's Government" (Article 2), and finally that "It is agreed that full jurisdiction, civil and criminal over British subjects and their property in the territory of Benin is reserved to her Britannic Majesty, to be exercised by such consular or other officers as Her Majesty shall appoint for the purpose ... The same jurisdiction is likewise reserved to her Majesty in the said territory of Benin over foreign subjects enjoying British protection, who shall be deemed to be involved in the expression 'British subjects' throughout this Treaty" (Article 3).

It is inconceivable that the Oba would accept the terms laid out in articles IV–IX, or that the Oba would knowingly bestow their dominion upon Queen Victoria for so little apparent remuneration. Under Article IV, the treaty states that "All disputes between the King of Benin and other Chiefs between him and British or foreign traders or between the aforesaid King and neighboring tribes which can not be settled amicably between the two parties, shall be submitted to the British consular or other officers appointed by Her Britannic Majesty to exercise jurisdiction in the Benin territories for arbitration and decision or for arrangement." Oba Ovonremwen was a tenacious man, which is contrary to the accounts of treaty portrayers such as Gallwey; he was not doltish.

The chiefs attest that the Oba did not sign the treaty because he was in the middle of an important festival which prohibited him from doing anything else (including signing the treaty). Ovoramwen maintained that he did not touch the white man's pen. Galway later claimed in his report that the Oba basically accepted the signing of the treaty in all respects. Despite the ambiguity over whether or not the Oba signed the treaty, the British officials easily accepted it as though he did.

The conflict of 1897

When people in Benin discovered Britain's true intentions were an invasion to depose the king of Benin, without approval from the king his generals ordered a preemptive attack on the British party approaching Benin City, including eight unknowing British representatives, who were killed. A punitive expedition was launched in 1897. The British force, under the command of Admiral Sir Harry Rawson, razed and burned the city, destroying much of the country's treasured art and dispersing nearly all that remained. The stolen portrait figures, busts, and groups created in iron, carved ivory, and especially in brass (conventionally called the "Benin Bronzes") are now displayed in museums around the world.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kingdom of Benin. |

References

- ↑ Ben-Amos, Paula Girshick (1995). The Art of Benin Revised Edition. British Museum Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-7141-2520-2.

- ↑ Strayer 2013, pp. 695-696.

- ↑ Ben Cahoon. "Nigerian Traditional States". Worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Africa's Glorious Legacy (1994) pp. 102–4

- ↑ The History of Africa: The Quest for Eternal Harmony.

- ↑ "The Benin City Pilgrimage Stations".

- ↑ Slavery and the Birth of an African City: Lagos, 1760--1900.

- ↑ Chapter 77, A History of the World in 100 Objects

- 1 2 3 Osadolor, Osarhieme Benson (23 July 2001). "The military system of Benin Kingdom, c. 1440–1897 (D)" (PDF). University of Hamburg: 4–264.

- ↑ Robert Sydney Smith, Warfare & diplomacy in pre-colonial West Africa, University of Wisconsin Press: 1989, pp. 54–62

- ↑ R.S. Smith, Warfare & diplomacy pp. 54–62

- ↑ Hernon, A. Britain's Forgotton Wars, p. 409 (2002)

Sources

- Strayer, Robert W. (2013). Ways of the World: A Brief Global History with Sources (2nd ed.). New York: Bedford/St.Martin's. ISBN 978-0312583460.

- Bondarenko, Dmitri M. (2005). "A homoarchic alternative to the homoarchic state: Benin Kingdom of the 13th–19th centuries". Social Evolution & History. 4 (2): 18–88.

- Bondarenko, Dmitri M. (2015). "The Benin Kingdom (13th – 19th centuries) as a megacommunity". Social Evolution & History. 14 (2): 46–76.

- Ezra, Kate (1992). Royal Art of Benin: the Perls Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870996320.

- Roese, P.M.; Bondarenko, D. M. (2003). A Popular History of Benin. The Rise and Fall of a Mighty Forest Kingdom. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 9780820460796.

Further reading

- Egharevba, Jacob U. (1968). Short History of Benin. Ibadan: Ibadan Up. OCLC 1037105916.

- Eisenhofer, Stefan (1995). "The origins of the Benin kingship in the works of Jacob Egharevba". History in Africa. 22: 141–163. JSTOR 3171912.

- Eisenhofer, Stefan (1997). "The Benin kinglist/s: some questions of chronology". History in Africa. 24: 139–156. doi:10.2307/3172022. JSTOR 3172022.

- Graham, James D. (1965). "The slave trade, depopulation and human sacrifice in Benin history: the general approach". Cahiers d'Études africaines. 5 (18): 317–334. JSTOR 4390897.

- Igbafe, Philip Aigbona (1979). Benin Under British Administration: The Impact of Colonial Rule on an African Kingdom, 1897-1938. London: Longman. OCLC 473877102.

- Palisot-Beauvois, A. (1800). "Notice sur le peuple de Bénin". Décade Philosophique (in French). 2e Trimestre (12): 141–151.

- Ryder, Alan Frederick Charles. Benin and the Europeans, (1485–1897). London: Longmans. OCLC 959073935.

External links

- Edo at Genealogical Gleanings

- The Story of Africa: Ife and Benin — BBC World Service

- The origin of Edos/Binis {source Edoworld}

- THE MILITARY SYSTEM OF BENIN KINGDOM, c. 1440–1897

- Nimmons, Fidelia (2012) Kingdom of Benin Blogs: Fiction, Myths and Lies

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art - Idia: The First Queen Mother of Benin