Beatles for Sale

| Beatles for Sale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by the Beatles | ||||

| Released | 4 December 1964 | |||

| Recorded | 11 August – 26 October 1964 | |||

| Studio | EMI Studios, London | |||

| Genre | Rock and roll,[1] country[2][3] | |||

| Length | 33:42 | |||

| Label | Parlophone | |||

| Producer | George Martin | |||

| the Beatles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Alternative cover | ||||

Cover for the Australian Parlophone LP | ||||

Beatles for Sale is the fourth studio album by the English rock band the Beatles. It was released on 4 December 1964 in the United Kingdom on EMI's Parlophone label. Eight of the album's fourteen tracks appeared on Capitol Records' concurrent release, Beatles '65, issued in North America only. The album marked a departure from the upbeat tone that had characterised the Beatles' previous work, partly due to the band's exhaustion after a series of tours that had established them as a worldwide phenomenon in 1964. The songs introduced darker musical moods and more introspective lyrics, with John Lennon adopting an autobiographical perspective in compositions such as "I'm a Loser" and "No Reply". The album also reflected the twin influences of country music and Bob Dylan, whom the Beatles met in New York in August 1964.

The Beatles recorded the album at EMI Studios in London in between their touring and radio engagements. Partly as a result of the group's hectic schedule, only eight of the tracks are original compositions, with cover versions of songs by artists such as Carl Perkins, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and Little Richard being used to complete the album. The sessions also produced a non-album single, "I Feel Fine" backed by "She's a Woman".

In Britain, Beatles for Sale held the number 1 spot for 11 of the 46 weeks that it spent in the top 20. The album was similarly successful in Australia, where the band's cover of Berry's "Rock and Roll Music" also topped the singles chart. One of the songs omitted from the US version of the album, "Eight Days a Week", became the Beatles' seventh number 1 in the US when issued as a single there in February 1965. Beatles for Sale was not released in the US until 1987, when the Beatles' catalogue was standardised for release on CD.

Background

When Beatles for Sale was being recorded, Beatlemania was at its peak.[4] In early 1964, the Beatles had made waves with their television appearances in the US, sparking unprecedented demand for their records there. Over June and July, the band played concerts in Denmark, the Netherlands and Hong Kong, toured Australia and New Zealand,[5] and then returned to Britain for a series of radio and television engagements and to promote their first feature film, A Hard Day's Night.[6] After performing further concerts in Sweden, they began recording the new album in London in mid August, only to then depart for a month-long tour of North America.[7]

Beatles for Sale was the Beatles' fourth album release in the space of 21 months.[8] Neil Aspinall, the band's road manager, later reflected: "No band today would come off a long US tour at the end of September, go into the studio and start a new album, still writing songs, and then go on a UK tour, finish the album in five weeks, still touring, and have the album out in time for Christmas. But that's what the Beatles did at the end of 1964. A lot of it was down to naiveté, thinking that this was the way things were done. If the record company needs another album, you go and make one."[9] Noting the subdued and melancholy tone of much of the album, producer George Martin recalled: "They were rather war weary during Beatles for Sale. One must remember that they'd been battered like mad throughout 1964, and much of 1963. Success is a wonderful thing but it is very, very tiring."[8]

Songwriting and musical styles

Although prolific, the songwriting partnership of John Lennon and Paul McCartney was unable to keep up with the demand for new material.[10][11] To make up for the shortfall in output, the Beatles resorted to including several cover versions on the album.[12] This had been their approach for their first two albums – Please Please Me and With the Beatles – but had been abandoned for A Hard Day's Night.[13] McCartney said of the combination on Beatles for Sale: "Basically it was our stage show, with some new [original] songs."[nb 1]

The album features eight Lennon–McCartney compositions.[19] In addition, the pair wrote both sides of the non-album single, "I Feel Fine" backed with "She's a Woman",[20] which accompanied the LP's release.[21] At this stage in their partnership, Lennon and McCartney rarely wrote together as before, but each would often contribute key parts to songs for which the other was the primary author.[22] Nevertheless, Lennon's level of contribution to Beatles for Sale outweighed McCartney's,[23][24] a situation that, as on A Hard Day's Night, author Ian MacDonald attributes to McCartney's commitment being temporarily sidetracked by his relationship with English actress Jane Asher.[25]

At the time, Lennon said of the album: "You could call our new one a Beatles country and western LP."[26] Music critic Tim Riley views the album as a "country excursion",[2] while MacDonald describes it as being "dominated by the [country-and-western] idiom".[3] The impetus for this new direction came partly from the band's exposure to US country radio stations while on tour;[27] in addition, it was a genre that Ringo Starr had long championed.[28] Lennon's "I Don't Want to Spoil the Party" was an early example of country rock, anticipating the Byrds' work in that style.[29] "I'm a Loser" was the first Beatles song to directly reflect the influence of Bob Dylan,[30] and served as a precursor to the folk-rock explosion of 1965.[31] Author Jonathan Gould highlights the influence of blues and country-derived rockabilly in the album's original compositions and in the inclusion of songs by Carl Perkins and Buddy Holly. He also comments that Dylan's acoustic folk sound was a style that the Beatles tended to identify as country music.[32]

McCartney later said that Beatles for Sale inaugurated a more mature phase for the band, whereby: "We got more and more free to get into ourselves. Our student selves rather than 'we must please the girls and make money' …"[33] According to author Peter Doggett, this period coincided with Lennon and McCartney being feted by London society, from which the pair found inspiration among a network of non-mainstream writers, poets, comedians, film-makers and other arts-related individuals. Doggett says that their social milieu in 1964 represented "new territory for pop" and a challenge to British class delineation as the Beatles introduced an "arty middle-class" sensibility to pop music.[34]

Recording

The sessions for Beatles for Sale began at EMI Studios on 11 August, one month after the release of A Hard Day's Night. The majority of the recording sessions took place during a three-week period beginning on 29 September, following the band's return from the US tour. Much of the production was done on "days off" from performances in the UK, and much of the songwriting was completed in the studio.

George Harrison recalled that the band had become more sophisticated about recording techniques: "Our records were progressing. We'd started out like anyone spending their first time in a studio – nervous and naive and looking for success. By this time we'd had loads of hits and were becoming more relaxed with ourselves, and more comfortable in the studio …"[33] The band continued to develop their sound through the use of four-track recording, which EMI had introduced in 1963. They were also allowed greater freedom to experiment by the record company and by George Martin, who was gradually relinquishing his position of authority over the Beatles, as their label boss, throughout 1964, and was increasingly open to their non-standard musical ideas.[35] The sessions resulted in the first use of a fade-in on a pop song, at the start of "Eight Days a Week",[36] and the first time that guitar feedback had been incorporated in a pop recording, on "I Feel Fine".[37]

The band introduced new instrumentation into their basic sound, as a way to illustrate the more nuanced style adopted by Lennon in his lyric writing.[38] This was especially evident in the range of percussion instruments, which, mainly played by Starr, included the band's first use of timpani, African hand drums[38] and chocalho.[39] According to MacDonald, the Beatles adopted a "less-is-more" approach in their arrangements; he cites "No Reply" as an example of the group beginning to "master the studio", whereby doubling basic parts and the use of reverb lent the performance "depth and space".[40] As he had done since With the Beatles, Harrison continued to vary his guitar sounds, favouring a Gretsch Tennessean guitar for the first time, in addition to using his twelve-string Rickenbacker 360/12.[41] Author André Millard describes this period as one in which the recording studio changed its identity from the Beatles' perspective, from a formal workplace into a "workshop" and "laboratory".[42]

Recording was completed on 26 October,[43] partway through the band's four-week tour of the UK.[44] On 18 October, the Beatles had rushed back to London from Hull,[45] to record the A-side of their forthcoming single, "I Feel Fine", and three of the album's cover tunes (in a total of five takes).[46] The band participated in several mixing and editing sessions before completing the project on 4 November.

Songs

Original compositions

"No Reply"

According to Lennon in 1972, Beatles music publisher Dick James was complimentary about "No Reply", saying that Lennon had provided "a complete story" whereas "before that, he thought my songs wandered off."[47] Reviewer David Rowley said that its lyrics "read like a picture story from a girl's comic" and evoked a picture "of walking down a street and seeing a girl silhouetted in a window, not answering the telephone".[48] Sequenced as the first track on Beatles for Sale, the song served as an uncharacteristic album opener, given its dramatic and resentful mood.[49]

MacDonald recognises the effectiveness of the acoustic guitar backing and the treatment given to Martin's piano part, which is rendered as "a darkly reverbed presence" rather than a distinct instrument.[50] Over this foundation, he continues, the vocals on the song are "massively haloed in echo", contributing to a middle-sixteen section that increases in intensity and is "among the most exciting thirty seconds" of all the Beatles' recordings.[51]

"I'm a Loser"

Unterberger singles out "I'm a Loser" as "one of the very first Beatles compositions with lyrics addressing more serious points than young love".[52] Rowley considered it to be an "obvious copy of Bob Dylan", as where Lennon refers to the listener as a "friend", Dylan does the same on "Blowin' in the Wind".[nb 2] He also said its intention was to "openly subvert the simple true love themes of their earlier work".[48] In Riley's view, "I'm a Loser" inaugurates a theme in Lennon's writing, in which his songs serve as "personal responses to fame".[54][nb 3]

"Baby's in Black"

As the third track on the album, "Baby's in Black" conveys the same sad and resentful outlook of the two preceding songs.[55] Music critic Richie Unterberger views it as "a love lament for a grieving girl that was perhaps more morose than any previous Beatles song".[56] It was the first song recorded for the album[57] and features a two-part harmony sung by Lennon and McCartney. McCartney recalled: "'Baby's in Black' we did because we liked waltz-time ... And I think also John and I wanted to do something bluesy, a bit darker, more grown-up, rather than just straight pop."[33] Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn cites the band's dedication to achieving a discordant twanging sound for Harrison's lead guitar part, and Martin's objection to the song opening with this sound, as an example of the Beatles breaking free of their producer's control for the first time.[57][58] To achieve the desired swelling effect, Lennon knelt on the studio floor and altered the volume control on Harrison's Gretsch as he played.[59][nb 4]

"I'll Follow the Sun"

"I'll Follow the Sun" was a reworking of an old song. McCartney recalled in a 1988 interview: "I wrote that in my front parlour in Forthlin Road. I was about 16 ... We had this R&B image in Liverpool, a rock and roll/R&B/hardish image with the leather. So I think songs like 'I'll Follow the Sun', ballads like that, got pushed back to later."[63] Author Mark Hertsgaard cites its inclusion as a reflection of the shortage of original material available to the band, since McCartney acknowledged that the song "wouldn't have been considered good enough" for their previous releases.[64] Martin nevertheless later named it as his favourite song on Beatles for Sale.[65]

"Eight Days a Week"

"Eight Days a Week" marked the first time that the Beatles brought in a partly formed song into the studio and completed the writing process as they recorded it.[42] Two recording sessions, totalling nearly seven hours, on 6 October were devoted to the song, during which Lennon and McCartney experimented with various techniques before settling on a final structure and arrangement. Each of the first six takes featured a strikingly different approach to the beginning and end sections of the song; the eventual chiming guitar-based introduction was recorded during a different session and edited in later. The song's opening fade-in served as a counterpoint to pop songs that close with a fade out.[66] Hertsgaard writes that the surprise provided by the fade-in was heightened for LP listeners due to the track being sequenced at the start of side two.[36]

Lennon referred to "Eight Days a Week" in his 1980 interview with Playboy magazine as "lousy".[66] In 1972, Lennon recalled that "Eight Days a Week" might have been made with the goal of being the theme song for the film Help!: "I think we wrote this when we were trying to write the title song for 'Help!' because there was at one time the thought of calling the film Eight Arms To Hold You. I think that's the story. I'm not sure."[67]

"Every Little Thing"

The dark theme of the album was balanced by "Every Little Thing", which Unterberger describes as a "celebration of what a wonderful girl the guy has".[68] McCartney said of the song: "'Every Little Thing', like most of the stuff I did, was my attempt at the next single ... but it became an album filler rather than the great almighty single. It didn't have quite what was required."[69] Musicologist Walter Everett says the chorus' incorporation of "leaden" parallel fifth harmonies, supported by Starr's timpani, was the inspiration for a proto-heavy metal version of the song recorded by the English progressive rock band Yes in 1969.[70]

"I Don't Want to Spoil the Party"

Lennon's "I Don't Want to Spoil the Party" returns to the sombre mood established by the opening three tracks.[55] MacDonald considers the performance to be the album's "most overt exercise in country-and-western", aided by the tight snare sound, Harrison's rockabilly-style guitar solo, and the despondent minor-third harmony part. MacDonald likens the effect to "I'm a Loser", in that Lennon's confessional tone is again couched in "a protective shell of pastiche".[71]

"What You're Doing"

The lyrics of "What You're Doing" concern McCartney's relationship with Jane Asher[72] and demonstrate an aggrieved tone that was uncharacteristic of his writing.[50][nb 5] The song features a syncopated drum pattern and a jangly Rickenbacker guitar riff,[75] as well as an instrumental coda that McCartney introduces by playing high up the neck of his Höfner bass.[76] A satisfactory arrangement for the song proved elusive until the band remade the track on the final day of the Beatles for Sale sessions.[24][77] While highlighting the studio techniques used to achieve the completed recording, MacDonald considers "What You're Doing" to be a possible rival to "I Feel Fine" as the Beatles' "first sound experiment".[78] McCartney later dismissed the track as "a bit of filler ... Maybe it's a better recording than it is a song ..."

Cover versions

Several of the album's cover versions had been staples of the Beatles' live shows in Hamburg and at The Cavern in Liverpool during the early 1960s.[28] These songs included Chuck Berry's "Rock and Roll Music", Buddy Holly's "Words of Love", and two by Carl Perkins: "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby", sung by Harrison, and "Honey Don't", sung by Starr.[nb 6] "Mr. Moonlight", which was originally recorded by Dr. Feelgood and the Interns, was Lennon's "beloved obscurity", according to Erlewine,[55] and the subject of a remake towards the end of the Beatles for Sale sessions. A cover of Little Willie John's "Leave My Kitten Alone" was taped on 14 August, during the same session as the discarded version of "Mr. Moonlight", but was omitted from the album.[59][80][nb 7]

A medley of "Kansas City" and "Hey, Hey, Hey, Hey" was sequenced as the final song on side one of the LP.[8] In McCartney's description, his performance on the track required "a great deal of nerve to just jump up and scream like an idiot"; his efforts were egged on by Lennon, who "would go, 'Come on! You can sing it better than that, man! Come on, come on! Really throw it!'" The medley was inspired by Little Richard, who similarly combined Leiber and Stoller's "Kansas City" with his own composition, "Hey, Hey, Hey, Hey!"[82][nb 8] Riley considers that, although McCartney's presence on Beatles for Sale appears relatively slight next to Lennon's, his performance of "Kansas City" goes some way to readdressing the balance.[23] Hertsgaard says that the irony evident in Harrison's delivery of "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby" "allows the Beatles to close the album with a not-so-veiled comment on the oddities of living inside Beatlemania".[83]

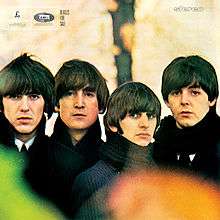

Artwork

The downbeat mood of Beatles for Sale was reflected in the album cover,[84] which shows the unsmiling, weary-looking Beatles[26][85] in an autumn scene in London's Hyde Park.[86] The cover photograph was taken by Robert Freeman, who recalled that the concept was briefly discussed with Brian Epstein and the Beatles beforehand, namely that he produce a colour image of the group shot at "an outside location towards sunset".[87] Music journalist Lois Wilson describes the result as "the very antithesis of the early-'60s pop star".[87] The cover carried no band logo or artist credit, and the album title was rendered in minuscule type compared with standard LP artwork of the time.[87]

Beatles for Sale was presented in a gatefold sleeve – a rare design feature for a contemporary pop LP[87] and the first of the Beatles' UK releases to be packaged in this way.[88] Part of the inner gatefold spread showed the band members in front of a photo montage of celebrities, including film stars Victor Mature, Jayne Mansfield and Ian Carmichael, all of whom the Beatles had met during 1964. Wilson comments that the adventurousness of this inner gatefold image anticipated Peter Blake's revolutionary cover design for the Beatles' 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[87]

According to music journalist Neil Spencer, the album's title was an apt comment on the band's unprecedented commercial value as entertainers, given the wealth of Beatles-related merchandise introduced over the previous year.[89] The sleeve notes for Beatles for Sale were written by Derek Taylor,[26] who, until a recent falling out with Epstein, had been the band's press officer throughout their rise to international stardom.[90] In his text, Taylor focused on what the Beatles phenomenon would mean to people of the future:[85]

There's priceless history between these covers. When, in a generation or so, a radioactive, cigar-smoking child, picnicking on Saturn, asks you what the Beatle affair was all about, don't try to explain all about the long hair and the screams! Just play them a few tracks from this album and he'll probably understand. The kids of AD2000 will draw from the music much the same sense of well being and warmth as we do today.[88]

Release

Beatles for Sale was released in the United Kingdom on EMI's Parlophone label on 4 December 1964.[91] On 12 December, it began a 46-week run in the charts, and a week later displaced A Hard Day's Night from the top position.[88] After seven weeks at number 1, the album's time at the top seemed over, but Beatles for Sale made a comeback on 27 February 1965, by dethroning The Rolling Stones No. 2 by the Rolling Stones and returning to the top spot for a week. After being again displaced by The Rolling Stones No. 2, Beatles for Sale would overtake it for a second time on 1 May, remaining there for another three weeks before being displaced by Dylan's The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. Eight of the album's tracks were later issued on two four-song EPs:[92] Beatles for Sale and Beatles for Sale No. 2, released in April and June 1965, respectively.[21]

The concurrent Beatles release in the United States, Beatles '65, included eight songs from Beatles for Sale, omitting the tracks "Kansas City/Hey, Hey, Hey, Hey!", "Eight Days a Week" (a number one hit single in the US in early 1965),[nb 9] "What You're Doing", "Words of Love", "Every Little Thing" and "I Don't Want to Spoil the Party". In turn, it added the track "I'll Be Back" from the British release of A Hard Day's Night and the single "I Feel Fine"/"She's a Woman".[93] The six omitted tracks finally got an LP release in America on Beatles VI in 1965. Beatles '65 was released eleven days after Beatles for Sale and became the fastest-selling album of the year in the United States.

The cover of the Australian release of the LP featured individual photographs of the Beatles taken at one of the group's Sydney concerts in June 1964.[94]

CD release

On 26 February 1987, Beatles for Sale was officially released on compact disc (catalogue number CDP 7 46438 2), as were the band's first three albums.[95][96] The following month, Beatles for Sale re-entered the UK albums charts, peaking at number 45.[97] Having been available previously only as an import in the US, the album was also issued on LP and cassette there on 21 July 1987.

Even though Beatles for Sale was recorded on four-track tape, the first CD version was available only in mono.[95] The album was digitally remastered and issued on CD in stereo for the first time on 9 September 2009.[96][98]

Critical reception

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The A.V. Club | B[99] |

| Blender | |

| Consequence of Sound | A–[101] |

| The Daily Telegraph | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Music Story | |

| Paste | 79/100[105] |

| Pitchfork Media | 9.3/10[1] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

The album received favourable reviews in the UK musical press.[87] Writing in the NME, Derek Johnson said that it was "worth every penny asked", adding: "It's rip-roaring, infectious stuff, with the accent on beat throughout." Chris Welch of Melody Maker found the music "honest" and inventive, and predicted: "Beatles For Sale is going to sell, sell, sell. It is easily up to standard and will knock out pop fans, rock fans, R&B and Beatles fans …"[87]

In a more recent assessment, Q found the album title to hold a "hint of cynicism" in depicting the Beatles as a "product" to be sold. AllMusic editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine said that "the weariness of Beatles for Sale comes as something of a shock" after "the joyous A Hard Day's Night". He also cited it as "the group's most uneven album" yet added that its best moments find them "moving from Merseybeat to the sophisticated pop/rock they developed in mid-career".[55]

Tom Ewing of Pitchfork Media said, "Lennon's anger and the band's rediscovery of rock 'n' roll mean For Sale's reputation as the group's meanest album is deserved".[1] Neil McCormick of The Daily Telegraph commented that "if this is a low point, they still sound fantastic", adding that "the Beatlemania pop songs are of a high standard, even if they are becoming slightly generic."[102] Writing in The Rolling Stone Album Guide, Rob Sheffield said that the album contains some poor cover versions yet "I'm a Loser" and "What You're Doing" indicate that the band were continuing to progress. He added: "The harmonies of 'Baby's in Black,' the hair-raising 'I still loooove her' climax of 'I Don't Want to Spoil the Party,' the eager hand claps in 'Eight Days a Week' – it all makes 'Mr. Moonlight' easy to forgive."[107]

Track listing

All tracks written by Lennon–McCartney, except where noted.

| Side one | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Lead vocals[108] | Length |

| 1. | "No Reply" | Lennon | 2:15 |

| 2. | "I'm a Loser" | Lennon | 2:30 |

| 3. | "Baby's in Black" | Lennon and McCartney | 2:04 |

| 4. | "Rock and Roll Music" (Chuck Berry) | Lennon | 2:31 |

| 5. | "I'll Follow the Sun" | McCartney | 1:49 |

| 6. | "Mr. Moonlight" (Roy Lee Johnson) | Lennon | 2:38 |

| 7. | "Kansas City/Hey, Hey, Hey, Hey" (Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller/Richard Penniman) | McCartney | 2:38 |

| Side two | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Lead vocals[109] | Length |

| 1. | "Eight Days a Week" | Lennon | 2:43 |

| 2. | "Words of Love" (Buddy Holly) | Lennon and McCartney | 2:04 |

| 3. | "Honey Don't" (Carl Perkins) | Starr | 2:57 |

| 4. | "Every Little Thing" | Lennon with McCartney | 2:04 |

| 5. | "I Don't Want to Spoil the Party" | Lennon with McCartney | 2:33 |

| 6. | "What You're Doing" | McCartney | 2:30 |

| 7. | "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby" (Carl Perkins) | Harrison | 2:26 |

Personnel

According to Ian MacDonald[108]

The Beatles

- John Lennon – lead, harmony and backing vocals; acoustic and rhythm guitars; harmonica; tambourine, handclaps

- Paul McCartney – lead, harmony and backing vocals; bass and acoustic guitars; piano, Hammond organ; handclaps

- George Harrison – harmony and backing vocals; lead (6- and 12-string) and acoustic guitars; African drum, handclaps; lead vocals on "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby"

- Ringo Starr – drums, tambourine, maracas, timpani, cowbell, packing case, bongos; lead vocals on "Honey Don't"

Additional musician

- George Martin – piano and producer

Charts and certifications

Chart positions

|

Certifications

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ George Harrison, the band's lead guitarist, had contributed one song to With the Beatles, "Don't Bother Me",[14] but no other composition of his appeared on a Beatles album until Help! in August 1965.[15] Commenting on this gap, Martin implied that Harrison's confidence was affected by his bandmates' indifference towards "You Know What to Do",[16] a Harrison composition that the group demoed in June 1964 along with Lennon's "No Reply".[17][18]

- ↑ The Beatles had already used "my friend" in this way in their 1963 B-side "I'll Get You" and in their March 1964 single "Can't Buy Me Love". In the case of those two love songs, MacDonald says the form of address conveyed "the casual etiquette of a coolly unromantic new age".[53]

- ↑ Later examples, according to Riley, include "Help!", "I'm Only Sleeping", "Baby, You're a Rich Man", "Don't Let Me Down" and "Instant Karma!"[54]

- ↑ The same volume-swell effect was a feature in some of the band's recordings from early 1965,[60] by which point Harrison had acquired a volume/tone-control pedal to create the sound.[61][62]

- ↑ Asher was also the muse for McCartney compositions such as "I'm Looking Through You" and "You Won't See Me", from Rubber Soul, "We Can Work It Out",[73] and "For No One", from Revolver.[74]

- ↑ Although Lennon and Harrison were the lead vocalists when the Beatles performed "Words of Love" over 1961–62, McCartney replaced Harrison for this 1964 studio recording. Similarly, Starr replaced Lennon as the singer of "Honey Don't".[79]

- ↑ Sung by Lennon, "Leave My Kitten Alone" was widely bootlegged[81] before receiving an official release on 1995's Anthology 1 compilation.[59]

- ↑ On the original Beatles for Sale sleeve, the song was listed as "Kansas City" (Leiber & Stoller). After the lawyers for Venice Music complained, the record label was revised to read "Medley: (a) Kansas City (Leiber/Stoller) (P)1964 Macmelodies Ltd./KPM. (b) Hey, Hey, Hey, Hey! (Penniman) Venice Mus. Ltd. (P)1964."

- ↑ Along with "No Reply" and "I'm a Loser", "Eight Days a Week" had always been considered for release as a single.[83]

References

- 1 2 3 Ewing, Tom (8 September 2009). "The Beatles: Beatles for Sale". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- 1 2 Riley 2002, p. 118.

- 1 2 MacDonald 2005, p. 129.

- ↑ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 90.

- ↑ Gould 2007, p. 238.

- ↑ Miles 2001, pp. 145–54.

- ↑ Miles 2001, pp. 159–60.

- 1 2 3 Lewisohn 2005, p. 53.

- ↑ The Beatles 2000, p. 161.

- ↑ Lewisohn 2005, p. 48.

- ↑ Everett 2001, p. 253.

- ↑ Everett 2001, p. 270.

- ↑ Hertsgaard 1996, pp. 56, 101–02.

- ↑ Unterberger 2006, p. 95.

- ↑ Miles 2001, pp. 203–04.

- ↑ Unterberger 2006, p. 96.

- ↑ Everett 2001, p. 248.

- ↑ Winn 2008, p. 186.

- ↑ Womack 2014, p. 110.

- ↑ Hertsgaard 1996, pp. 101, 103.

- 1 2 Everett 2001, p. 252.

- ↑ Norman 1996, p. 257.

- 1 2 Riley 2002, p. 119.

- 1 2 Miles 2001, p. 181.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, p. 155.

- 1 2 3 Gould 2007, p. 255.

- ↑ Quantick, David (2010). "The Beatles Beatles for Sale Review". BBC Music. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- 1 2 Miles 2001, p. 179.

- ↑ Kingsbury, McCall & Rumble 2012, p. 106.

- ↑ Lewisohn 1996, p. 168.

- ↑ Unterberger, Richie (2001). "Folk Rock: An Overview". richieunterberger.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ↑ Gould 2007, p. 258.

- 1 2 3 The Beatles 2000, p. 160.

- ↑ Doggett 2015, p. 327.

- ↑ Millard 2012, pp. 178–79.

- 1 2 Hertsgaard 1996, p. 104.

- ↑ Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles 'I Feel Fine'". AllMusic. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- 1 2 Schaffner 1978, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Lewisohn 2005, p. 49.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, pp. 131–32.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, p. 129fn.

- 1 2 Millard 2012, p. 179.

- ↑ Babiuk 2002, p. 146.

- ↑ Miles 2001, pp. 173, 175.

- ↑ Miles 2001, p. 174.

- ↑ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ & Hertsgaard 1996, pp. 104–05.

- 1 2 & Rowley.

- ↑ Spencer 2002, pp. 130–31.

- 1 2 MacDonald 2005, p. 131.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, p. 132.

- ↑ Unterberger 2005a.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, p. 105.

- 1 2 Riley 2002, pp. 118–19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Beatles Beatles for Sale". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ Unterberger 2005b.

- 1 2 Lewisohn 2005, p. 47.

- ↑ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 106.

- 1 2 3 Babiuk 2002, p. 134.

- ↑ Babiuk 2002, pp. 134, 159.

- ↑ Lewisohn 2005, p. 54.

- ↑ Everett 2009, p. 52.

- ↑ Lewisohn 2005, p. 12.

- ↑ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 105.

- ↑ Beatles For Sale mini-documentary, 2009 CD re-issue

- 1 2 Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles 'Eight Days a Week'". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Alan (February 1972). "Lennon/McCartney Singalong: Who Wrote What". Hit Parader. Derby, Connecticut: Charlton Publications Inc.

- ↑ Unterberger 2005e.

- ↑ Miles 1997, p. 174.

- ↑ Everett 2001, pp. 258, 403.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, pp. 129–30.

- ↑ Spencer 2002, p. 131.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, pp. 131, 180.

- ↑ Sounes 2010, p. 144.

- ↑ Everett 2001, p. 260.

- ↑ Spencer 2002, pp. 131–32.

- ↑ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 49, 51.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, pp. 130–31.

- ↑ Miles 2001, pp. 180–81.

- ↑ Unterberger 2006, p. 102.

- ↑ Spencer 2002, p. 133.

- ↑ Miles 2001, p. 180.

- 1 2 Hertsgaard 1996, p. 101.

- ↑ Riley 2002, p. 115.

- 1 2 Hertsgaard 1996, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Womack 2014, pp. 110–11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Spencer 2002, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 Womack 2014, p. 111.

- ↑ Spencer 2002, p. 130.

- ↑ Talevski 1999, p. 415.

- ↑ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 41.

- ↑ Womack 2014, pp. 111–12.

- ↑ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Sawyer, Mark (6 October 2012). "Fixing a hole – the great lost Aussie Beatles collection". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- 1 2 Badman 2001, p. 386.

- 1 2 Womack 2014, p. 109.

- ↑ Badman 2001, p. 387.

- ↑ Collett-White, Mike (7 April 2009). "Original Beatles digitally remastered". Reuters. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ↑ Klosterman, Chuck (8 September 2009). "Chuck Klosterman Repeats The Beatles". The A.V. Club. Chicago. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ Du Noyer, Paul (2004). "The Beatles Beatles for Sale". Blender. Archived from the original on 4 May 2006. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ Balderrama, Anthony (17 September 2009). "Album Review: The Beatles – Beatles for Sale [Remastered]". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- 1 2 McCormick, Neil (4 September 2009). "The Beatles – Beatles For Sale, review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ Larkin 2006, p. 489.

- ↑ "The Beatles > Discographie de The Beatles (in French)". Music Story. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ↑ Kemp, Mark (8 September 2009). "The Beatles: The Long and Winding Repertoire". Paste. p. 59. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ Brackett & Hoard 2004, p. 51.

- ↑ Brackett & Hoard 2004, p. 52.

- 1 2 MacDonald 2005, pp. 122–41.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, pp. 122–41; except "I Don't Want to Spoil the Party": Winn 2008, p. 273.

- ↑ Kent, David (2005). Australian Chart Book (1940–1969). Turramurra: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-44439-5.

- ↑ "Offiziellecharts.de – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "Beatles | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "Dutchcharts.nl – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Beatles for Sale (1987 Version)" > "Chart Facts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ "Austriancharts.at – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Ultratop.be – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Ultratop.be – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "The Beatles: Beatles for Sale" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Italiancharts.com – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale". Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Charts.org.nz – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale". Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Spanishcharts.com – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale". Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Swedishcharts.com – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale". Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Swisscharts.com – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale". Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2009 Albums". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ "Canadian album certifications – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale". Music Canada. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ "British album certifications – The Beatles – Beatles for Sale". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 15 September 2013. Select albums in the Format field. Select Gold in the Certification field. Enter Beatles for Sale in the search field and then press Enter.

- ↑ "American album certifications – Beatles, The – The Beatles_ Story". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 15 September 2013. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH.

- ↑ "Beatles albums finally go platinum". British Phonographic Industry. BBC News. 2 September 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

Sources

- Babiuk, Andy (2002). Beatles Gear: All the Fab Four's Instruments, from Stage to Studio. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-731-8.

- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-2684-6.

- Brackett, Nathan; with Hoard, Christian (eds) (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th edn). New York, NY: Fireside/Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Doggett, Peter (2015). Electric Shock: From the Gramophone to the iPhone: 125 Years of Pop Music. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-847922182.

- Everett, Walter (2001). The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men through Rubber Soul. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514105-9.

- Everett, Walter (2009). The Foundations of Rock: From "Blue Suede Shoes" to "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes". New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531024-5.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. London: Piatkus. ISBN 978-0-7499-2988-6.

- Hertsgaard, Mark (1996). A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the Beatles. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-33891-9.

- Kingsbury, Paul; McCall, Michael; Rumble, John W. (eds) (2012). The Encyclopedia of Country Music (2nd edn). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539563-1.

- Larkin, Colin (ed.) (2006). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th edn). London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531373-4.

- Lewisohn, Mark (1996). The Complete Beatles Chronicle. Chronicle Press. ISBN 1-85152-975-6.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (2nd rev. edn). Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-733-3.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Millard, André (2012). Beatlemania: Technology, Business, and Teen Culture in Cold War America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0525-4.

- Norman, Philip (1996) [1981]. Shout!: The Beatles in Their Generation. New York, NY: Fireside. ISBN 0-684-83067-1.

- Riley, Tim (2002) [1988]. Tell Me Why – The Beatles: Album by Album, Song by Song, the Sixties and After. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81120-3.

- Rowley, David (2002). Beatles for Sale. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84018-567-8.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Sounes, Howard (2010). Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-723705-0.

- Spencer, Neil (2002). "Beatles For Sale: Some Product". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Beatlemania (The Early Years – April 1, 1962 to December 31, 1964). London: Emap. pp. 130–33.

- Talevski, Nick (1999). The Encyclopedia of Rock Obituaries. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-7548-5.

- Unterberger, Richie (2005b). "Review of "Baby's in Black"". AllMusic. Retrieved 7 November 2005.

- Unterberger, Richie (2005e). "Review of "Every Little Thing"". AllMusic. Retrieved 7 November 2005.

- Unterberger, Richie (2006). The Unreleased Beatles: Music & Film. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-892-6.

- Winn, John C. (2008). Way Beyond Compare: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume One, 1962–1965. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

- Womack, Kenneth (2007). Long and Winding Roads: The Evolving Artistry of the Beatles. New York, NY: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1746-6.

- Womack, Kenneth (2014). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39171-2.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Beatles for Sale |