Church of the Nativity

| Church of the Nativity | |

|---|---|

The interior of the Church of the Nativity circa 1936, photographed by Lewis Larsson | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Bethlehem, West Bank |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°42′15.50″N 35°12′27.50″E / 31.7043056°N 35.2076389°ECoordinates: 31°42′15.50″N 35°12′27.50″E / 31.7043056°N 35.2076389°E |

| Affiliation | Shared: Greek Orthodox Church, Armenian Apostolic Church, and Roman Catholic Church with minor Coptic Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox rights[1] |

| Status | Active |

| Architectural description | |

| Architectural type | Byzantine (Constantine the Great and Justinian I) |

| Architectural style | Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | 325 |

| Completed | 565 |

| Official name: Birthplace of Jesus: the Church of the Nativity and the Pilgrimage Route, Bethlehem | |

| Type | Cultural Heritage |

| Criteria | iv, vi |

| Designated | 2012[2] |

| Reference no. | 1433 |

| State Party | State of Palestine |

| Region | Western Asia |

.jpg)

The Church of the Nativity, also Basilica of the Nativity (Arabic: كَنِيسَةُ ٱلْمَهْد; Greek: Βασιλική της Γεννήσεως; Armenian: Սուրբ Ծննդյան տաճար; Latin: Basilica Nativitatis) is a basilica located in Bethlehem in the West Bank. The grotto it contains holds a prominent religious significance to Christians of various denominations as the birthplace of Jesus. The grotto is the oldest site continuously worshipped in Christianity, and the basilica is the oldest major church in the Holy Land.

The church was originally commissioned in 327 by Constantine the Great and his mother Helena on the site that was traditionally considered to be the birthplace of Jesus. That original basilica was completed sometime between 333-339. It was destroyed by fire during the Samaritan revolts of the 6th century, and a new basilica was built in 565 by Byzantine Emperor Justinian, who restored the architectural tone of the original.[3]

The Church of the Nativity, while remaining basically unchanged since the Justinian reconstruction, has seen numerous repairs and additions, especially from the Crusader period, such as two bell towers (now gone), wall mosaics and paintings (partially preserved).[4] Over the centuries, the surrounding compound has been expanded, and today it covers approximately 12,000 square meters, comprising three different monasteries: one Greek Orthodox, one Armenian Apostolic, and one Roman Catholic,[5] of which the first two contain bell-towers built during the modern era.[4]

The silver star marking the spot where Christ was born was stolen in 1847. Some assert that this was a contributing factor in the Crimean War against the Russian Empire;[6] Others assert that the war grew out of the wider european situation.[7]

The Church of the Nativity is a World Heritage Site and was the first to be listed under Palestine by UNESCO.[8] The site is also on UNESCO's List of World Heritage in Danger.[9]

The status quo of Holy Land sites is a 250-year old understanding among religious communities that applies to the site.[10][11]

History

Holy site before Constantine (ca. 4 BC–327 CE)

The holy site known as the Nativity Grotto is thought to be the cave in which Jesus of Nazareth was born. In 135, Emperor Hadrian had the site above the Grotto converted into a worship place for Adonis, the Greek god of beauty and desire.[12][13] Jerome noted in 420 that the grotto had been consecrated to the worship of Adonis, and that a sacred grove was planted there in order to completely wipe out the memory of Jesus from the world.[12] Some modern scholars dispute this argument and insist that the cult of Adonis-Tammuz originated the shrine and that it was the Christians who took it over, substituting the worship of Jesus.[14] The antiquity of the association of the site with the birth of Jesus, however, is attested by Justin Martyr (c. 100–165) who noted in his Dialogue with Trypho that the Holy Family had taken refuge in a cave outside of town:

But when the Child was born in Bethlehem, since Joseph could not find a lodging in that village, he took up his quarters in a certain cave near the village; and while they were there Mary brought forth the Christ and placed Him in a manger, and here the Magi who came from Arabia found Him.[15]

Additionally, early Christian theologian and Greek philosopher Origen of Alexandria (185–c. 254) wrote:

In Bethlehem the cave is pointed out where He was born, and the manger in the cave where He was wrapped in swaddling clothes. And the rumor is in those places, and among foreigners of the Faith, that indeed Jesus was born in this cave who is worshipped and reverenced by the Christians.[16]

Constantinian basilica (327–529 or 556)

The first basilica on this site was begun by Helena of Constantinople, the mother of Emperor Constantine I. The construction started in 327 under the supervision of Bishop Makarios of Jerusalem and was completed a few years later[17] - it was already visited in 333 by the Bordeaux Pilgrim[18] and was officially dedicated on 31 May 339.[19]

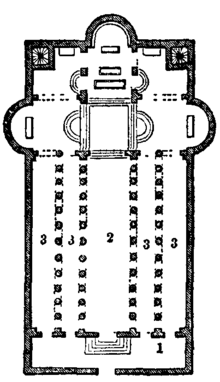

Construction of this early church was carried out as part of a larger project following the First Council of Nicaea during Constantine's reign, aimed to build churches on the supposed sites of the life of Jesus.[17][20] The design of the basilica centered around three major architectural sections: [21]

- At the eastern end, an apse in a polygonal shape (broken pentagon, rather than the once proposed, but improbable full octagon), encircling a raised platform with an opening in its floor of ca. 4 metres diametre that allowed direct view of the Nativity site underneath. An ambulatory with side rooms surrounded the apse.[21]

- A five-aisled basilica in continuation of the eastern apse, one bay shorter than the still standing Justinian reconstruction.[21]

- A porticoed atrium.[21]

The structure was burned and destroyed in one of the Samaritan Revolts of 529 or 556, in the second of which Jews seem to have joined the Samaritans.[22][5]

Justinian's basilica (565)

The basilica was rebuilt in its present form in 565 by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I.

The Persians under Khosrau II invaded Palestine and conquered nearby Jerusalem in 614, but they did not destroy the structure. According to legend, their commander Shahrbaraz was moved by the depiction above the church entrance of the Three Magi wearing the garb of Persian Zoroastrian priests, so he ordered that the building be spared.[23] [24]

Crusader to Mamluk period (12th-15th centuries)

The Church of the Nativity was used as the primary coronation church for Crusader kings, from the second ruler of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1100 and until 1131.[25] The Crusaders undertook extensive decoration and restoration on the basilica and grounds,[25] a process that continued until 1169,[5] from 1165-69 even through a rare cooperation between the Catholic king Amalric I of Jerusalem and the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos, who was his father-in-law.[26]

The Khwarezmian Turks desecrated the Church of the Nativity in April 1244, leaving the roof in poor condition.[27][28] The Duchy of Burgundy committed resources to restore the roof in August 1448,[28] and multiple regions contributed supplies to have the Church roof repaired in 1480: England supplied the lead, the Second Kingdom of Burgundy supplied the wood, and the Republic of Venice provided the labor.[23]

Nineteenth century

Earthquakes inflicted significant damage to the Church of the Nativity between 1834 and 1837.[29] The 1834 Jerusalem earthquake damaged the church's bell tower, the furnishings of the cave on which the church is built, and other parts of its structure.[30] Minor damages were further inflicted by a series of strong aftershocks in 1836 and the Galilee earthquake of 1837.[29][31]

By 1846, the Church of the Nativity and its surrounding site lay in disrepair and vulnerable to looting. Much of the interior marble flooring was looted in the early half of the 19th century, much of which was transferred to use in other buildings around the region, including the Haram ash-Sharif (Temple Mount) in Jerusalem. The religiously significant silver star marking the exact birthplace of Jesus was stolen in 1846 from the Grotto of the Nativity.[32] The church was under the control of the Ottoman Empire, but around Christmas 1852, Napoleon III forced the Ottomans to recognise France as the "sovereign authority" over Christian holy sites in the Holy Land.[33] The Sultan of Turkey replaced the silver star at the Grotto, complete with a Latin inscription, but the Russian Empire disputed the change in authority. They cited the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca and then deployed armies to the Danube area. As a result, the Ottomans issued firmans essentially reversing their earlier decision, renouncing the French treaty, and restoring the Greeks to the sovereign authority over the churches of the Holy Land for the time being, thus increasing local tensions—and all this fuelled the conflict between the Russian and the Ottoman empires over the control of holy sites around the region.

Twentieth century to the present

The passageway which connects St. Jerome's Cave and the Cave of the Nativity was expanded in February 1964, allowing easier access for visitors. American businessman Stanley Slotkin was visiting at the time and purchased a quantity of the limestone rubble, more than a million irregular fragments about 5 mm (0.20 in) across. He sold them to the public encased in plastic crosses, and they were advertised in infomercials in 1995.[34]

Approximately 50 armed Palestinians wanted by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) locked themselves in the church in April 2002 during the Second Intifada, holding hostage 200 monks and other Palestinians—some of whom served as human shields for the terrorists.[35] The IDF did not break into the building, but they prevented the entry of food and cut telephone lines. The siege lasted 39 days, and some of the terrorists were shot by IDF snipers.

Curtains caught fire in the grotto beneath the church on 27 May 2014, which resulted in some slight damage.[36]

The Church undertook a major renovation starting in September 2013,[37] about to be completed as of April 2018. Italian restoration workers uncovered a seventh mosaic angel in July 2016, which was previously hidden under plaster.[38]

Property and administration

The property rights, liturgical use and maintenance of the church are regulated by a set of documents and understandings known as the Status Quo.[1] The church is owned by three church authorities, the Greek Orthodox (most of the building and furnishings), the Armenian Apostolic and the Roman Catholic (each of them with lesser properties).[1] The Coptic Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox are holding minor rights of worship at the Armenian church in the northern transept, and at the Altar of Nativity.[1] There have been repeated brawls among monk trainees over quiet respect for others' prayers, hymns and even the division of floor space for cleaning duties.[39][40] The Palestinian police have been called to restore peace and order.[41]

Site architecture and layout

The centrepiece of the Nativity complex is the Grotto of the Nativity, a cave which enshrines the site where Jesus is said to have been born.

The core of the complex connected to the Grotto consists of the Church of the Nativity itself, and the adjoining Roman Catholic Church of St. Catherine north of it.

Outer courtyard

Bethlehem's main city square, Manger Square, is an extension of the large paved courtyard in front of the Church of the Nativity and St Catherine's. Here crowds gather on Christmas Eve to sing Christmas carols in anticipation of the midnight services.

Church, or Basilica, of the Nativity

The main Basilica of the Nativity is maintained by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. It is designed like a typical Roman basilica, with five aisles formed by Corinthian columns, and an apse in the eastern end containing the sanctuary.

The basilica is entered through a very low door called the "Door of Humility."[42]

The church's interior walls features medieval golden mosaics once covering the side walls, which are now in large parts lost.[42]

The original Roman-style floor of the basilica has been covered over with flagstones, but there is a trap door in the floor which opens up to reveal a portion of the original mosaic pavement from the Constantinian basilica.[42]

There are 44 columns separating the aisles from each other and from the nave, some of which are painted with images of saints, such as the Irish monk St. Cathal (fl. 7th century), the patron of the Sicilian Normans, St. Canute (c. 1042-1086), king of Denmark, and St. Olaf (995-1030), king of Norway.[43]

The east end of the church consists of a raised chancel, closed by an apse containing the main altar and separated from the chancel by a large gilded iconostasis.

A complex array of sanctuary lamps is placed throughout the entire building.

The open ceiling exposes the wooden rafters, recently restored. The previous 15th-century restoration used beams donated by King Edward IV of England, who also donated lead to cover the roof; however, this lead was taken by the Ottoman Turks, who melted it down for ammunition to use in war against Venice.

Stairways on either side of the chancel lead down to the Grotto.

Grotto of the Nativity

The Grotto of the Nativity, the place where Jesus is said to have been born, is an underground space which forms the crypt of the Church of the Nativity. It is situated underneath its main altar, and it is normally accessed by two staircases on either side of the chancel. The Grotto is part of a network of caves, which are accessed from the adjacent Church St Catherine's. The tunnel-like corridor connecting the Grotto to the other caves is normally locked.

The cave has an eastern niche said to be the place where Jesus was born, which contains the Altar of Nativity. The exact spot where Jesus was born is marked beneath this altar by a 14-pointed silver star with the Latin inscription Hic De Virgine Maria Jesus Christus Natus Est-1717 (Here Jesus Christ was born to the Virgin Mary-1717). It was installed by the Catholics in 1717, removed - allegedly by the Greeks - in 1847, and replaced by the Turkish government in 1853. The star is set into the marble floor and surrounded by 15 silver lamps representing the three Christian communities: six belong to the Greek Orthodox, four to the Catholics, and five to the Armenian Apostolic. The Altar of the Nativity is maintained by the Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic churches.

Roman Catholics are in charge of a section of the Grotto known as the "Grotto of the Manger", marking the traditional site where Mary laid the newborn Baby in the manger. The Altar of the Magi is located directly opposite from the manger site.

Church of St. Catherine

The adjoining Church of St. Catherine is a Roman Catholic church dedicated to St. Catherine of Alexandria, built in a more modern Gothic Revival style. It has been further modernized according to the liturgical trends which followed Vatican II.

This is the church where the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem celebrates Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. Certain customs in this Midnight Mass predate Vatican II, but must be maintained because the status quo was legally fixed by a firman (decree) in 1852 under the Ottoman Empire, which is still in force today.

The bas-relief of the Tree of Jesse is a 3.75 by 4 metres (12.3 by 13.1 ft) sculpture by Czesław Dźwigaj which was recently incorporated into the Church of St. Catherine as a gift of Pope Benedict XVI during his trip to the Holy Land in 2009. It represents an olive tree as the Tree of Jesse, displaying the genealogy of Jesus from Abraham through Joseph, as well as symbolism from the Old Testament. The upper portion is dominated by a crowned figure of Christ the King in an open-armed pose blessing the Earth. It is situated along the passage used by pilgrims making their way to the Grotto of the Nativity.[44]

Caves accessed from St. Catherine's

Several chapels are found in the caves accessed from St. Catherine's, including the Chapel of Saint Joseph commemorating the angel's appearance to Joseph, commanding him to flee to Egypt (Matthew 2:13); the Chapel of the Innocents, commemorating the children killed by Herod (Matthew 2:16–18); and the Chapel of Saint Jerome, in the underground cell where tradition holds he lived while translating the Bible into Latin (the Vulgate).

Tombs

According to a tradition not sustained by history, the tombs of four Catholic saints are said to be located beneath the Church of the Nativity, in the caves accessible from the Church of St. Catherine:[45]

- Jerome, whose remains are said to have been transferred to the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome

- Paula, a disciple and benefactor of Jerome

- Eustochium, the daughter of St. Paula

- Eusebius of Cremona, a disciple of Jerome. A different tradition holds that he is buried in Italy

A number of ancient through-shaped tombs can be seen in the Catholic-owned caves adjacent to the Nativity Grotto and St Jerome's Cave, some of them inside the Chapel of the Innocents; more tombs can be seen on the southern, Greek-Orthodox side of the Basilica of the Nativity, also presented as being those of the infants murdered by Herod.

World Heritage Site

In 2012, the church complex became the first Palestinian site to be listed as a World Heritage Site by the World Heritage Committee at its 36th session on 29 June.[46] It was approved by a secret vote[47] of 13–6 in the 21-member committee, according to UNESCO spokeswoman Sue Williams,[48] and following an emergency candidacy procedure that by-passed the 18-month process for most sites, despite the opposition of the United States and Israel. The site was approved under criteria four and six.[49] The decision was a controversial one on both technical and political terms.[48][50] It has also been placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger as it is suffering from damages due to water leaks.[9]

Restoration (2013-2018)

The basilica was placed on the 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites by the World Monuments Fund:

The present state of the church is worrying. Many roof timbers are rotting, and have not been replaced since the 19th century. The rainwater that seeps into the building not only accelerates the rotting of the wood and damages the structural integrity of the building, but also damages the 12th-century wall mosaics and paintings. The influx of water also means that there is an ever-present chance of an electrical fire. If another earthquake were to occur on the scale of the one of 1834, the result would most likely be catastrophic. ... It is hoped that the listing will encourage its preservation, including getting the three custodians of the church—the Greek Orthodox Church, the Armenian Orthodox Church, and the Franciscan order—to work together, which has not happened for hundreds of years. The Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority would also have to work together to protect it.[51][52]

In 2010, the Palestinian Authority announced that a multimillion-dollar restoration programme was imminent.[53]

The initial phase of the restoration work was completed in early 2016. The project is partially funded by Palestinians and conducted by a team of Palestinian and international experts. New windows have been installed, structural repairs on the roof have been completed and art works and mosaics have been cleaned and restored. Although overwhelmingly Muslim, Palestinians consider the church a national treasure and one of their most visited tourist sites. President Mahmoud Abbas has been actively involved in the project, which is led by Ziad al-Bandak.[54]

Gallery

Icon of Mary and Jesus ("Mary of Bethleem") near the staircase to the Nativity Grotto

Icon of Mary and Jesus ("Mary of Bethleem") near the staircase to the Nativity Grotto Constantine's 4th-century mosaic floor rediscovered in 1934

Constantine's 4th-century mosaic floor rediscovered in 1934 The Door of Humility, main entrance into the Church

The Door of Humility, main entrance into the Church This fourteen-point silver star from beneath the main altar in the Grotto of the Nativity marks the traditional spot of Jesus' birth

This fourteen-point silver star from beneath the main altar in the Grotto of the Nativity marks the traditional spot of Jesus' birth The Altar of the Nativity, beneath which is the star marking the spot where tradition says Jesus was born

The Altar of the Nativity, beneath which is the star marking the spot where tradition says Jesus was born- Christmas Eve 2006 in Manger Square.

The upper part of the Altar of the Nativity

The upper part of the Altar of the Nativity

External links

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Church of the Nativity. |

References

- 1 2 3 4 Cust, L. G. A. (1929). The Status Quo in the Holy Places. H.M.S.O. for the High Commissioner of the Government of Palestine.

- ↑ "Unesco, Birthplace of Jesus: the Church of the Nativity and the Pilgrimage Route, Bethlehem". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ Cohen, Raymond. Conflict and Neglect: Between Ruin and Preservation at the Church of the Nativity.

- 1 2 Custodia terrae sanctae, Bethlehem Sanctuary: Crusader bell towers

- 1 2 3 Shomali, Qustandi. "Church of the Nativity: History & Structure". Retrieved 8 April 2018.

Today, the compound of the Nativity church covers an area of approximately 12,000 square meters and includes, besides the Basilica, the Latin convent in the north, the Greek convent in the south-east and the Armenian convent in the south-west. A bell-tower and sacristy were built adjoining the south-east corner of the Basilica.

- ↑ LaMar C. Berrett (1996). Discovering the World of the Bible. Cedar Fort. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-910523-52-3.

- ↑ Clive Ponting (2011). The Crimean War: The Truth Behind the Myth. Random House. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-4070-9311-6.

- ↑ Lazaroff, Tovah (29 June 2012). "UNESCO: Nativity Church heritage site in 'Palestinian Authority'". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Birthplace of Jesus: Church of the Nativity and the Pilgrimage Route, Bethlehem". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ UN Conciliation Commission (1949). United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine Working Paper on the Holy Places.

- ↑ Cust, L. G. A. (1929). The Status Quo in the Holy Places. H.M.S.O. for the High Commissioner of the Government of Palestine.

- 1 2 Ricciotti, Giuseppe (1948). Vita di Gesù Cristo. Tipografia Poliglotta Vaticana. p. 276 n.

- ↑ Maier, Paul L. (2001). The First Christmas: The True and Unfamiliar Story.

- ↑ Craveri, Marcello (1967). The Life of Jesus. Grove Press. pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Dialogue with Trypho, chapter LXXVIII

- ↑ Contra Celsum, book I, chapter LI

- 1 2 Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. pp. 30, 222. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.

- ↑ Custodia terrae sanctae, Bethlehem Sanctuary: Anonymous Pilgrim of Bordeaux, accessed 2018-04-10

- ↑ Jerome Murphy-O'Connor (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. Oxford Archaeological Guides. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-19-923666-4. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ↑ Moffatt, Marian; et al. (2003). A World History of Architecture.

- 1 2 3 4 Peter Gemeinhardt, Katharina Heyden, eds. (2012). Heilige, Heiliges und Heiligkeit in spätantiken Religionskulturen. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110283976. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- ↑ Crown, Alan D; et al. (1993). A Comparison to Samaritan Studies. p. 55.

- 1 2 The Palestine Exploration Fund, The Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem: Early Christian Period After 529

- ↑ Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades Vol. I: The First Crusade and the Foundations of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, p. 10, Cambridge University Press, 1987

- 1 2 Hazzard, Harry W. (1977). A History of the Crusades. Vol. IV.

- ↑ Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, The Basilica of Nativity: Restoration works continue to reveal hidden jewels, posted 2016-06-21, accessed 2018-04-8

- ↑ "After Centuries, Bethlehem's Church of the Nativity to Get New Roof". 27 November 2011.

- 1 2 Pringle, Denys (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Vol. I.

- 1 2 Black, Aden (1851). A Cyclopedia of Biblical Literature. vol. I.

- ↑ The Holy Land. Oxford University Press. 2008.

- ↑ Smith, George Adam (1907). Jerusalem: the topography, economics and history from the earliest times to A.D. 70. Vol. 1.

- ↑ Kraemer, Joel L. (1980). Jerusalem: problems and prospects.

- ↑ Royle. p. 19.

- ↑ Dart, John (12 October 1996). "Rocks of Faith". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Cohen, Ariel (24 April 2002). "The Nativity Sin". National Review Online. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ "Fire breaks out at Bethlehem's Church of Nativity". WKBN. Associated Press. 27 May 2014.

- ↑ "Church of Nativity restoration". United Press International. Washington. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Italians find Church of Nativity's 7th angel". Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata. Rome. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ "Cleaning turns into a broom-brawl at the Church of the Nativity". MSNBC. 28 December 2011. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Monks brawl at Jerusalem shrine". BBC News. 9 November 2008.

- ↑ "Palestinian territories (News), Christianity (News), Israel (News), Religion (News), World news, Christmas (Life and style), Greece (News), Armenia (News)". The Guardian. 28 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Madden, A. M. (2012). "A Revised Date for the Mosaic Pavements of the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem". Ancient West and East. 11: 147–190.

- ↑ Jerome Murphy-O'Connor (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. Oxford Archaeological Guides. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923666-4. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ↑ "Płaskorzeźba w dare". Dziennik Polski (in Polish). 13 May 2009. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- ↑ Jerome Murphy-O'Connor (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. Oxford Archaeological Guides. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-19-923666-4. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ↑ "Bethlehem's Church of the Nativity Could Be Israel's First World Heritage Site". Global Heritage Fund. 15 June 2012. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ "UNESCO urgently lists Church of Nativity as world heritage". IBN Live News. 29 June 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- 1 2 "UNESCO makes Church of Nativity as endangered site". Ynetnews.com. 29 June 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ "Birthplace of Jesus: Church of the Nativity and the Pilgrimage Route, Bethlehem". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "UN grants Nativity Church 'endangered' status". Middle East. Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Church of the Holy Nativity". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ Kumar, Anugrah (28 November 2011). "Bethlehem's Nativity Church to Get Overdue Repairs". The Christian Post.

- ↑ "Topic Galleries". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ "Sci/Tech – Science & Technology: Breaking news and opinions".