Attappadi

| Attappadi | |

|---|---|

| nature reserve | |

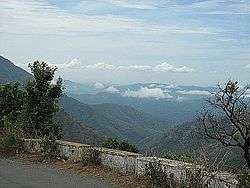

Attappadi Hills of Western Ghat | |

Attappati Reserve Forest | |

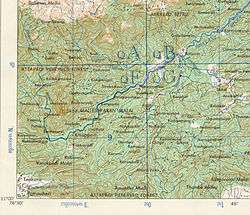

| Coordinates: 11°5′0″N 76°35′0″E / 11.08333°N 76.58333°ECoordinates: 11°5′0″N 76°35′0″E / 11.08333°N 76.58333°E | |

| Country |

|

| State | Kerala |

| District | Palakkad district |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Malayalam, English, Tamil, Badaga, Tribal language |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Vehicle registration | KL-50 |

| Nearest city | Palakkad |

Attappadi Reserve Forest is a protected area comprising 249 km² of land covering the westernmost part of the 745 km² Attappadi block of Mannarghat Taluk in Palakkad district of Kerala, south India.[1] It is one of many reserved forests and protected forests of India.

There is a Government Goat Farm at Attappadi village which has the "Attappadi Black" breed available.[2]

Geography

Attappadi is an extensive mountain valley at the headwaters of the Bhavani River nestled below the Nilgiri Hills of the Western Ghats. It is bordered to the east by Coimbatore district in Tamil Nadu, on the north by the Nilgiris, south by the Palghat taluk and on the west by Karimba-I and II, Pottassery-I and II, and Mannarghat revenue villages of Mannarghat taluk of the Palghat District and Ernad taluk of the Malappuram district.

The 249 km² Attappadi Reserve Forest is an informal buffer zone bordering the Silent Valley National Park to the West.[3] 81 km² of this forest was separated to become most of the new 94 km² Bhavani Forest Range which is part of the 147.22 km² Silent Valley Buffer Zone formally approved by the Kerala Cabinet on 6 June 2007. The Cabinet also sanctioned 35 staff to protect the area and two new forest stations in Bhavani range at Anavai and Thudukki. The zone is aimed at checking the illicit cultivation of ganja, poaching and illicit brewing in areas adjacent to Silent Valley and help long-term sustainability of the protected area.[4]

The elevation of Attappati valley ranges from 750 meters (2,460 ft) to the Malleswaran peak at 11°6′32″N 76°33′8″E / 11.10889°N 76.55222°E which rises to 1,664 meters (5,459 ft) from the center of the valley. The Bhavani River flows from the Northwest around the mountain in a tight bend past Attappadi village and continues to the Southeast.

Geology

Gneisses are the predominant rocks in Attappadi. All rock types of Attappadi other than supracrustals could be categorized into seven broad types. They are charnockite, hornblende gneiss, migmaititic amphibolite, quartz biotite gneiss, quartz-feldspathic gneiss, biotite granite gneiss, and pegmatite. Among the rock types charnockite, hornblende gneiss, migmatitic amphibolite, quartz biotite gneiss, quartz-feldspathic gneiss, and biotite granite gneiss have been identified that belong to the Peninsular Gneissic Complex. The granite and pegmatite of Attappad9 represent the post-kinematic intrusives. Many dolerite dykes also have been reported from this area. The bands and layers of ultramafics and mafic rocks (Ultramafic and mafic rocks represented by metapyroxinite, talc-tremolite-actinolite schist and amphibolites) of varying dimension, BIF, sillimamite/kyanite bearing quartzite and fuchsite quartzite occurring within the Peninsular Gneissic Complex of Attappadi area designated as Attappadi Supracrustals. Remnants and enclaves of Attappadi supracrustals occur within the gneisses. BIF is another important rock type occurring in close association with the metapyroxinite and amphibolites.

Attappadi is unique in that a number of rock types varying in composition from ultramafic to metapelites occur as supracrustals. The metapelites are of granulite facies and the ultramafics are of greenschist facies and the enclosing gneisses represent amphibolites facies.

The area had undergone polyphase deformation. The planar S0, is defined by the layering within chemogenic precipitate (BIF). The earliest folds F1, apart from being tight and appressed occur in intrafolial positions and also constitute the rootless folds. This folding has given rise to an axial planar penetrative foliation and is defined mainly by hornblende and to a lesser extend by chlorite and is co-parallel to the lithoboundaries identified as S0. S1 schistosity is defined by hornblende and chlorite, and this mineralogical association suggests that the deformation occurred under upper greenschist to lower amphibolite facies conditions. The subsequent F2 resulted in refolding of S1 and transposition of S1 subparallel to the F2 axial trace. The most prominent planar structures are the discrete mylonitic foliation S2 attributed the regional NE-SW trending Bhavani shear. Mylonite development, biotitization, chloritization and microgranulation are found associated with these surfaces.[5]

Gold Mineralization

Mani 1965 reported the panning for gold by local miners in Siruvani River of Attappadi. Detailed studies to assess the economic potential of Attappadi area was carried out subsequently by Geological Survey of India. However, no primary gold prospects were identified. Nair 1993 carried out the geomorphologic mapping combined with panning of Siruvani River which led to the discovery of primary gold mineralization in epigenetic quartz vein in Puttumala. The veining, mineralization and associated lithology of this deposit appear to be typical of greenstone-hosted lode gold deposit. On the basis of mode of occurrence two types of gold mineralization are recognized in Attappadi,

- Primary gold mineralization is associated with quartz veins intruding to AS and PGC.

- Placer deposit along the bank of Siruvani River.

The Geological Survey of India has confirmed the high gold bearing potentiality of the rocks in the 834sq km area of the Attappadi. Gold mineralization is known from Kottathara, Puttumala, Pothupadi, Mundaiyur and Kariyur-Vannathorai Prospects of Attappadi. Gold occurs in quartz veins traversing in BIF, metavolcanics, and hornblende and biotite gneiss. Deccan Gold Mines Limited later confirmed the earlier reported gold grades and have given the following values, Kottathara prospect: Three zones have been delineated and the prospect has ore resource of grading 13.63g/t gold according to Geological survey of India. While tracing the NE extension of Kottathara prospect, stringers of quartz analyzing 9 g/t 35 g/t and 49g/t gold have been picked up in stream beds.

- Puttumala prospect: A 60 cm sample of vein quartz carrying galena (lead sulfide) from old trenches showed high spot values of gold up to 21g/t.

- Pothupadi Prospect: A sample of vein quartz traversing amphibolite assayed 4 g/t gold.

- Mundaiyur Prospect: Gold occurs in quartz veins over a length of 300 m with gold-bearing sulphides enveloping the quartz veins.

- Kariyur-Vannathorai Prospect: Samples of vein quartz have shown gold contents ranging from 3 to 20 g/t.

In Attappadi region gold grains are found only in native state and occur in different shapes and sizes. Visible specks of gold were noticed in the samples collected from veins, particularly where the associated sulphides have been subjected to weathering and leaching resulting in the formation of limonite. Gold grains with maximum dimension of 2 mm were reported. Pyrite is the dominant sulfide phase within the quartz lodes (occurring as stringers and fracture fillings). Chalcopyrite, covellite, chalcocite, and galena are commonly observed in the mineral assemblage.[5]

Climate

Attappadi RF in the southwest portion of Mannarghat Forest Division receives a high rainfall of 4700 mm (185 in). Moving eastward along the Attappadi valley towards Agali,[6] the rainfall steadily decreases to a low of 900 mm.[7]

Population

There are 192 hamlets in Attappadi. Because of the inward migration of settlers from the mainland of Kerala, the tribal population of Attappadi had decreased from around 90 percent in 1951 to around 40 percent only, by 2001.[8] The tribal population of the valley is mostly Muduga, Irula, Kurumba tribal people, a few Badagas and a section of settlers from Tamil Nadu and Other Districts of Kerala.[9] This valley falls under the Kannada speaking region as per the linguistic survey and history of Colonel Wilks.[10]

There are mainly three Communities of tribes living in Attapadi they are irulas, Mudugas and kurumbas.

Kurumbas

(Kurumbar, Kurumban) Kurumbar are most primitive tribes. they are distributed in Attappadi Block Panchayat of Palakkad District. They are the earliest inhabitants of Attappadi area and are called ‘Palu Kurumba’ to distinguish them from the ‘Alu Kurumba’ of Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu State. The language spoken by them is a mixture of Tamil and Malayalam. The traditional social organisation of Kurumbar is similar to that of Mudugar and Irular communities residing in that area. Kurumbar mostly living in Reserve and Vested Forest areas have been practising shifting cultivation called ‘Panja Krishi’. They cultivate Ragi, Thuvara, Chama etc. They are experts in cattle rearing. They are also collectors of non timber forest produces. They maintain a community life by sharing land and labour. Kurumbas were once hunters and gatherers and shifting cultivators of Attappadi Valley. However, among the five PVTG of Kerala, the younger generation of the Kurumba community have shown more interest than others in organising themselves and getting educated. Now they are living in 19 'ooru'. Kurumba community is settled in Agali and Pudur Grama Panchayats of Palakkad District.

- Thadikund

- Thazhe Anavai

- Mele Anavai

- Kadukamanna

- Murukala

- Palappada

- kinattikkara

- Thudukki

- Mele Thudukki

- Galazy

- Kurukkathikkallu

- Gottiyarkandi

- Anakkattiyur

- Pazhur

- Mele Bhoothayar

- Thazhe Bhoothayar

- Idavani

- Mele Moolakombu

- Ooradam.

There are 543 families with a population of 2251. The family size is 4.14. As the population consists of 1128 males and 1123 females the sex ratio is 1000:996. Ninety eight per cent of Kurumba population is settled in Pudur Grama Panchayat and the rest in Agali Grama Panchayat.

Mudugar

As already mentioned Mudugar distributed in Palakkad district, is one among the three communities of Attappadi region. They have a distinct identity because of their traditional right to climb the Malleeswaran Peak and light the lamp on the ‘Sivaratri’ day. They have a dialect of their own known as ‘Muduga Bhasha’ Mudugar have the institutions of ‘Ooru Moopan’, (Headman)‘Bhandari’ (Treasurer), ‘Kuruthalai’ (Assistant) and ‘Mannukaran’ (soil expert). This system is similar to the traditional social organisation of the other two tribal communities of Attappadi, viz; Irular and Kurumbar. Mudugar practise settled agriculture with many features of shifting cultivation. They used to cultivate ‘ragi’, ‘chama’, ‘thina’ etc. They also collect non timber forest produces. Their land has been alienated as they have little knowledge to secure documents relating to their possession. The working population among them has become agricultural laboures as agriculture and animal husbandary, have slowly been changing as their subsidiary occupations. The community is pro-educative and inputs to agriculture can sustain their livelihood means. There are 1274 families and 4668 population of Mudugar community. The population consists of 2225 males and 2443 females, registering the family size as 3.66 and sex ratio of 1000 : 1098. Mudugar community is settled in Palakkad District. In Pathanamthitta and Kannur Districts one family each of Mudugar community has been identified. Mudugar community is distributed in 9 Grama Panchayats in Palakkad but majority of them are settled in Agali and Pudur Grama Panchayats in Attappadi region.

Irular, Irulan

Irular community is distributed in Palakkad District and they are mainly concentrated in Attappadi region. They are also found in Tamil Nadu. They have a dialect of their own called ‘Irula bhasha’, which has more affinity to Tamil. Their traditional social organisation is endowed with various functionaries, namely; ‘Ooru Moopan’ (Chieftain),‘Bhandari’ (Treasurer), ‘Kuruthala’ (assistant to Chieftain) ‘Mannukaran’ (soil expert), ‘Marunnukaran’ (healer) etc. These positions are hereditary and succession is by the son. This traditional institutions play a decisive role in the social control mechanism of Irular community. Earlier Irular were hunters, gatherers and shifting cultivators. Now they have become experts in settled agriculture and also work as agricultural labourers. The major area in Attappadi falls under rain shadow region and as such the important crops raised by them under dry farming are ‘Ragi’, ‘Chama’, ‘Thina’, ‘Cholam’, ‘Thuvara’, ‘Kadala’ etc. For cultivation they stay away from their hamlet and erect temporary huts. Irular community has attractive songs and dances which tell about their forest, cultivation, emotions etc. They have been empowered through ‘Thaikula Sangham’, exclusively for women and ‘Ooruvikasana Samithi’ organised under the Attappadi Hills Area Development Society. Their livelihood means have been affected due to the influx of non tribal Scheduled Tribes of Kerala : Report on the Socio Economic Status Chapter 2 : Demographic Features of Scheduled Tribes 10 population both from other parts of Kerala and Tamil Nadu.Technically, Irular community has representation in four districts, namely; Palakkad, Thiruvananthapuram, Idukki and Malappuram.

There are 7617 families of Irular community, of which 7614 are in Palakkad District and one each in the other three districts. The family size of Irular community is 3.48 Irular population comes to 26,525. They have the credit of being the fifth largest community of Scheduled Tribes in Kerala. They constitute 6.22 per cent of the Scheduled Tribes. In Palakkad they are settled in 10 Grama Panchayats, with the concentration in the 3 Grama Panchayats of Attappadi region.

Approximately 95.20 per cent of Irular community is located in Agali (9474), Sholayur (9076) and Pudur (6703) Grama Panchayats of Attappadi.

Pudussery (907) and Malampuzha (245) are the other two Grama Panchayats with a sizable population of Irular community. Since the population consists of 13163 males and 13362 females, the sex ratio of Irular community is 1000 : 1015.

Infrastructure

The local governments of Attappadi are the Agali, Puthur and Sholayur Grama Panchayats.

Health

There are three government primary health centres (PHC), one community health centre (CHC) and 28 subcentres in this 745-km² block. All hamlets are serviced by an effective government health extension program using trained tribal health volunteers.[11] The tribal women of 80 Attapadi hamlets are conducting a vocal campaign against liquor and ganja which has received public support from the Governor.[12] The Society of the Missionaries of St. Thomas operates the St. Thomas Ashram in Nelippathy for providing services to the tribal people of Attapadi including a 15-bed Hospital and health clinic with Lab, X-ray, Dental X-ray, ECG, Pharmacy and ambulance.there is a Tribal Super Speciality Hospital in Agali for the health care of the people with some operation theatres and facilities.

Education

Only one government school in Agali is having the facilities of a full equipped education centre. A college of applied sciences (IHRD College) is started in Agali, in the year 2010 for the higher education.on 2012 there is another college has started at Agali. Govt. College Attappadi is the first Arts and science College in the Attappadi region established under the Govt. sector in 2012.

Transportation

There are frequent local buses from Anakkatti village in Attappadi to the nearest town of Nelippathy (16 km) and Mannarghat (38 km).Sholayur

Accommodation

There are private lodges with boarding and lodging facilities in and around Agali and Goolikadavau. The PWD Guest house and the guest house at AHADS can also be utilised for accommodation.

Development projects

In 1970 the State Planning Board assessed Attappati as the most backward block in the state and the first Integrated Tribal Development Project in Kerala was initiated there. Since then, the state government has implemented several special development projects including the Attappadi Co-operative Farming Society, the Western Ghats Development Programme, the Attappadi Valley Irrigation Programme and the People's Planning Programme implemented in Attappadi in 1997–2002.

A monumental palace-like "Bharat Yatra Centre" at Agali was established in 1984 by a former Prime Minister, Chandra Shekhar, to provide employment training in weaving, pottery, embroidery and food processing to the women of this rural area. The property was occasionally occupied personally by Chandra Shekar but employment training never happened. The leaders of Girijan Sevak Samaj (GSS), the major tribal body in Attappadi, stated that the center was built on original tribal lands possessed illegally.

In 2000 The Centre at Attappadi and its huge building were deserted and unoccupied.[13]

Many of these projects were not well adapted to traditional adivasi culture and beliefs so about 80 per cent of the tribal population is still living in abject poverty. Attappadi demonstrates how difficult it is for a modern government development process to succeed in a traditional self-sustaining indigenous peoples (adivasi) community. Tribal people are a majority of the Attappadi population but have a high illiteracy rate of 49.5 per cent and a lack of political and administrative awareness. The majority of project managers and new land owners are from other parts of Kerala, Tamil Nadu and other states.

The Attappadi Comprehensive Environmental Conservation and Wasteland Development Project was established in 1995, with local operations managed from their Agali Headquarters.[14] This project has Rs. 2.19 billion ($5,000,000) development assistance loan from the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and is implemented by the Attappadi Hills Area Development Society.[15] a state government agency. AHADS has made good quantified achievements[16] that will bring long term benefit to the valley.

Integrated Rural Technology Centre (IRTC), Palakkad is implementing the NABARD WADI Tribal development project in Attappadi.[17]

Attappadi Social Service Organisation (ASSO) is one of the major Social Service Organization functioning in Attappadi. It successfully implemented World Bank aided 'Jalanidhi' project to provide drinking water facility for the tribal community.

the other main development project that depend upon a social media, face book and a whats app group the face book book have appox 23k likes and whats app page also having to support fb they have 11 nos admin panel and a 3 team leaders also having this group also having small local area groups too

Festival

The Sivarathri festival is celebrated at the chemmannur Malleswaran temple by the tribals during the month of February/March. The Malleswaran peak is worshipped as a gigantic Shivalinga by the adivasis who celebrate the Sivarathri festival there with great fervour.

At the Ayyappan temple in Agali, Ayyappan Vilakku is celebrated in January.

The Vishu festival is celebrated at Pattimalam in Sree Vandikotti Mariyamma Thune Temple.

References

- ↑ Suchitra M.(8/8/2005) "Remote adivasis face health care chasm" Free India Media, retrieved 4/3/2007 "Remote adivasis..." Archived 12 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Public Relations Department, Govt. of Kerala, "Where to get" Department of Amimal Husbandry, retrieved 4/1/2007 "Where to get" Archived 27 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ keralaatbest.com (2002) "Palgat", retrieved 4/1/2007 Palgat Archived 18 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ J The Hindu, Front page, retrieved 8 June 2007 Cabinet approves buffer zone for Silent Valley 6 June 2007

- 1 2 pradeepsz PhD thesis Genesis of gold mineralization in Attappadi

- ↑ "Agali, attappadi - Wikimapia". www.wikimapia.org.

- ↑ Asian Nature Conservation Foundation (2006) "NILAMBUR-SILENT VALLEY-COIMBATORE – PERSPECTIVE FOR THE RESERVE" retrieved 29 March 2007 PERSPECTIVE FOR THE RESERVE Archived 2 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://indianexpress.com/article/india/regional-india/survival-of-tribals-in-attappady-region-under-threat-as-infant-deaths-continue/

- ↑ Hockings, Paul (1988). Counsel from the Ancients: A Study of Badaga Proverbs, Prayers, Omens and Curses. Berlin. ISBN 9783110113747.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 9, p. 301. DSAL. p. 301.

- ↑ COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH PROJECT PDF file

- ↑ Hindustan times, Kerala, ( 21 March 2007) "Kalam starts Attapadi anti-liquor campaign", retrieved 21 April 2007 Attapadi anti-liquor campaign

- ↑ Interdisciplinary Biannual Journal Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. PDF file

- ↑ "ACME Mapper 2.1". mapper.acme.com.

- ↑ AHADS index Archived 3 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Attappadi Hills Area Development Society, (2005) "Achievements" Retrieved 4/4/2007 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ "IRTC - WADI PROJECT".

External links

![]()