Atayal people

| Tayal, Tayan | |

|---|---|

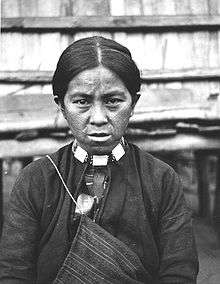

A Tayal woman with tattoo on her face as a symbol of maturity, which was a tradition for both males and females. The custom was prohibited during Japanese rule. | |

| Total population | |

| 89,741 (Jan 2018) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Taiwan | |

| Languages | |

| Atayal, Mandarin, Taiwanese Hokkien | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Seediq, Truku, Kavalan, Taiwanese Aborigines |

The Atayal (Chinese: 泰雅; pinyin: Tàiyǎ), also known as the Tayal and the Tayan,[1] are an indigenous group of people from Taiwan. In 2014, the Atayal people numbered 85,888. This was approximately 15.9% of Taiwan's total indigenous population, making them the third-largest indigenous group.[2][3]

Etymology

The meaning of Atayal is "genuine person" or "brave man".

Origins

The first record of Atayal inhabitance is found near the upper reaches of the Zhuoshui River. However, during the late 17th century they crossed the Central Mountain Ranges into the wilderness of the east. They then settled in the Liwu River valley. Seventy-nine Atayal villages can be found here.

Genetics

Taiwan is home of a number of Austronesian indigenous groups since before 4,000 BC.[4] However, genetic analysis suggests that the different peoples may have different ancestral source populations originating in mainland Asia, and developed in isolation from each other. The Atayal people are believed to have migrated to Taiwan from Southern China or Southeast Asia.[5] Genetic studies have also found similarities between the Atayal and other people in the Philippines and Thailand, and to a lesser extent with south China and Vietnam.[6] The Atayal are genetically distinct from the Amis people who are the largest indigenous group in Taiwan, as well as from the Han people, suggesting little mingling between these people.[7] Studies on Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) polymorphisms suggest ancient migrations of two lineages of the various peoples into Taiwan approximately 11,000-26,000 years ago.[8]

Recent DNA studies show that the Lapita people and modern Polynesians have a common ancestry with the Atayal and the Kankanaey people of the northern Philippines.[9]

The Atayal are visibly different from the Han Chinese of Taiwan.[10] Intermarriage with Chinese also produced a significant number of Atayal-Chinese mixed offspring and celebrities such as Vivian Hsu, Vic Zhou, Yuming Lai, Kao Chin Su-mei.

Folklore

According to stories told by their elders, the first Atayal ancestors appeared when a stone, Pinspkan, cracked apart. There were three people, but one decided to go back into the stone. One man and one woman who lived together for a very long time and loved each other very much. But the boy was shy and wouldn't dare approach her. Whereupon, the girl came up with an idea. She left her home and found some coal with which to blacken her face so she could pose as a different girl.

After several days, she crept back into their home and the boy mistook her for another girl and they lived happily ever after. Not long after, the couple bore children, fulfilling their mission of procreating the next generation. The Atayal custom of face tattooing may have come from the girl blackening her face in the story.

Culture

Lifestyle

The Atayal people have a well-developed culture. They originally lived by fishing, hunting, gathering, and growing crops on burned-off mountain fields. Atayal also practice crafts such as weaving, net knotting, and woodworking. They also have traditional musical instruments and dances.

The Atayal are known as skilled warriors. In a practice illegal since the Japanese Colonial Era (1895 –1945), to earn his facial tattoo a man had to bring back at least one human head; these heads, or skulls, were highly honored, given food and drink, and expected to bring good harvests to the fields. (See Headhunting.) The Atayal were known to be fierce fighters as observed in the case of the Wushe Incident, in which the Atayal participated in an uprising against colonial Japanese forces.

Lalaw Behuw was the weapon of the Atayals.[11] Traditional Aboriginal weapons have featured in movies.[12]

Traditional dress

The Atayal are proficient weavers, incorporating symbolic patterns and designs on their traditional dress. The features are mainly of geometric style, and the colors are bright and dazzling. Most of the designs are argyles and horizontal lines. In Atayal culture, the horizontal lines represent the rainbow bridge which leads the dead to where the ancestors' spirits live. Argyles, on the other hand, represent ancestors' eyes protecting the Atayal. The favorite color of this culture is red because it represents blood and power.

Facial tattoos

.jpg)

The Atayal people are also known for using facial tattooing and teeth filing in coming-of-age initiation rituals. The facial tattoo, in Squliq Tayal, is called ptasan. In the past both men and women had to show that they had performed a major task associated with an adult before their faces could be tattooed. For a man, he had to take the head of an enemy, showing his valor as a hunter to protect and provide for his people, while women had to be able to weave cloth. A girl would learn to weave when she was about ten or twelve, and she had to master the skill in order to earn her tattoo. Only those with tattoos could marry, and, after death, only those with tattoos could cross the hongu utux, or spirit bridge (the rainbow) to the hereafter.

Male tattooing is relatively simple, with only two bands down the forehead and chin. Once a male came of age he would have his forehead tattooed; after fathering a child, his bottom chin was tattooed. For the female, tattooing was done on the cheek, typically from the ears across both cheeks to the lips forming a V shape. While tattooing on a man is relatively quick, on a female it may take up to ten hours.[5]

Tattooing was performed only by female tattooists. The tattooing was performed using a group of needles lashed to a stick called atok tapped into the skin using a hammer called totsin. Black ash would then be rubbed into the skin to create the tattoo. Healing could take up to a month.[5]

The Japanese banned the practice of tattooing in 1930 because of its association with headhunting. With the introduction of Christianity, the practice declined, and tattoos are now only seen on the elderly even though it is no longer banned. However, some young people in recent years have attempted to revive the practice.[5] By 2018 only one traditionally tattooed Atayal person survived, Lawa Piheg, who was tattooed when she was 8; she did not want the practice to continue.[13]

Atayal in modern times

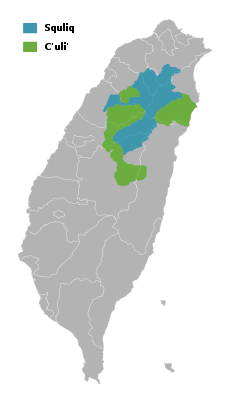

The Atayal people in Taiwan live in central and northern Taiwan. The northernmost village is Ulay (Wulai in Chinese), about 25 kilometers south of central Taipei. The name Ulay is derived from /qilux/, hot, because of the hot springs on the riverbank. The Wulai Atayal Museum in the town is a place to learn about the history and culture of the Atayal.

By 2003 the mainly Christian community of Smangus had become well known as a tourist destination, and an experiment in communalism.[14]

Many Atayal are bilingual, but the Atayal language still remains in active use.

Notable Atayal people

- Kao Chin Su-mei, actress, singer and politician

- Vic Chou, actor and member of pop group F4

- Albee Huang, actress and singer

- Yuming Lai, singer of rock duo Y2J

- Irene Luo, singer

- Joanne Tseng, actress and member of pop duo Sweety

- Landy Wen, singer

- Jane Huang, singer of rock duo Y2J

- Vivian Hsu, actress

- Stephen Rong 榮忠豪, actor, singer, and host

See also

References

- ↑ Atayal, Digital Museum of Taiwan Indigenous Peoples.

- ↑ Hsieh Chia-chen & Jeffrey Wu (February 15, 2014). "Amis remains Taiwan's biggest aboriginal tribe at 37.1% of total". Focus Taiwan.

- ↑ Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (DGBAS). National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan). Preliminary statistical analysis report of 2000 Population and Housing Census Archived 2007-03-12 at the Wayback Machine.. Excerpted from Table 28:Indigenous population distribution in Taiwan-Fukien Area. Accessed PM 8/30/06

- ↑ Merritt Ruhlen (1994). The origin of language: tracing the origin of the mother tongue. Wiley, New York. pp. 177–180.

- 1 2 3 4 Margo DeMello (30 May 2014). Inked: Tattoos and Body Art around the World. ABC-CLIO. pp. 34–36. ISBN 978-1610690751.

- ↑ Chen KH, Cann H, Chen TC, Van West B, Cavalli-Sforza L (1985). "Genetic markers of an aboriginal Taiwanese population". Am J Phys Anthropol. 66: 327–337. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330660310. PMID 3857010.

- ↑ Rachel A. Chow; Jose L. Caeiro; Shu-Juo Chen; Ralph L. Garcia-Bertrand; Rene J. Herrera (2005). "Genetic characterization of four Austronesian-speaking populations" (PDF). Journal of Human Genetics. 50: 550–559. doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0294-0. PMID 16208426.

- ↑ Tajima A, Sun CS, Pan IH, Ishida T, Saitou N, Horai S (2003). "Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms in nine aboriginal groups of Taiwan: implications for the population history of aboriginal Taiwanese". Human Genetics. 113 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-0945-1. PMID 12687351.

- ↑ Gibbons, Ann (3 October 2016). "'Game-changing' study suggests first Polynesians voyaged all the way from East Asia". Science. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ Dudding, Adam (15 March 2015). "New Zealand's long-lost Taiwanese cuzzies". Stuff Destinations. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ http://nccur.lib.nccu.edu.tw/bitstream/140.119/34564/9/25900309.pdf http://conference.masalu.org.tw/webadmin/upload/1-6-1-%E9%84%AD%E5%85%89%E5%8D%9A--%E4%BF%AE%E6%AD%A3%E5%BE%8C.pdf http://e-dictionary.apc.gov.tw/tay/4/DLText.htm https://www.flickr.com/photos/94448433@N00/5865993483 http://flickrhivemind.net/Tags/knife,laraw http://www.flickriver.com/photos/tags/%E7%95%AA%E5%88%80/interesting/ https://www.flickr.com/photos/talovich/5865996049 https://www.flickr.com/photos/talovich/5866548974 http://etnics.es/foro/index.php?topic=1700.5;wap2 http://www.appledaily.com.tw/appledaily/article/forum/20070510/3462555/

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2016-08-25. http://travel.cnn.com/hong-kong/visit/seediq-bale-401232/ http://savageminds.org/2011/12/31/the-translation-of-seediq-bale/ http://screenanarchy.com/2012/08/-fantasia-2012-wrap-all.html

- ↑ "'My face was tattooed when I was eight'". BBC News. 25 September 2018. Interview with last tattooed person, with historical photographs of instruments, tattooed people, etc.

- ↑ "Returning to the land of the ancestors." Taipei Times, Aug 10 2003. Accessed 10/21/06.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atayal people. |