War of the Golden Stool

| War of the Golden Stool | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Frederick Mitchell Hodgson Major James Willcocks | Otumfour, Queen Yaa Asantewaa | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,007 casualties | 2,000 casualties | ||||||

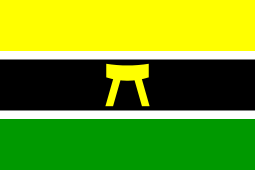

The War of the Golden Stool, also known as the Yaa Asantewaa War, the Third Ashanti Expedition, the Ashanti Uprising, or variations thereof, was the final war in a series of conflicts between the British Imperial government of the Gold Coast (later Ghana) and the Ashanti Empire (later Ashanti Region), an autonomous state in West Africa that fractiously co-existed with the British and its vassal coastal tribes.

When the Ashanti began rebelling against British rule, the British attempted to put down the unrest. Furthermore, the British governor, Sir Frederick Mitchell Hodgson, demanded that the Asante turn over to the British the Golden Stool, i.e. the throne and symbol of Asante sovereignty.[1]

The war ended with the Ashanti maintaining its de facto independence. Even though the Ashanti were annexed into the British Empire, they ruled themselves with little reference to the colonial power. However, when the British colony of the Gold Coast became the first independent sub-Saharan African country in 1957, Ashanti was subsumed into the newly created Ghana.

The Golden Stool

Hodgson advanced toward Kumasi with a small force of British soldiers and local levies, arriving on the 25 March 1900. Hodgson, as representative of a powerful nation himself, was accorded traditional honors upon entering the city with children singing "God Save the Queen" to Lady Hodgson.[2] After ascending a platform, he made a speech to the assembled Ashanti leaders. The speech, or the closest surviving account that comes through an Ashanti translator, reportedly read:[3]

| “ | Your King Prempeh I is in exile and will not return to Ashanti. His power and authority will be taken over by the Representative of the Queen of Britain. The terms of the 1874 Peace Treaty of Fomena, which required you to pay for the cost of the 1874 war, have not been forgotten. You have to pay with interest the sum of £160,000 a year. Then there is the matter of the Golden Stool of Ashanti. The Queen is entitled to the stool; she must receive it.

Where is the Golden Stool? I am the representative of the Paramount Power. Why have you relegated me to this ordinary chair? Why did you not take the opportunity of my coming to Kumasi to bring the Golden Stool for me to sit upon? However, you may be quite sure that though the Government has not received the Golden Stool at his hands it will rule over you with the same impartiality and fairness as if you had produced it. |

” |

Not understanding the significance of the stool, Hodgson clearly had no inkling of the storm his words would produce; the suggestion that he, a foreigner, should sit upon and defile the Golden Stool, the very embodiment of the Ashanti state, and very symbol of the Ashanti peoples, living, dead, and yet to be born, was far too insufferable for the crowd. In a speech, Yaa Asantewaa, the queen mother of the Ejisu dominion within the Ashanti kingdom, rallied resistance to the colonialists: "Now I have seen that some of you fear to go forward to fight for our king. If it were in the brave days, the days of Osei Tutu, Okomfo Anokye, and Opoku Ware, chiefs would not sit down to see their king taken away without firing a shot. No white man [Obroni] could have dared to speak to a chief of the Ashanti in the way the Governor spoke to you chiefs this morning. Is it true that the bravery of the Ashanti is no more? I cannot believe it. It cannot be! I must say this, if you, the men of Ashanti, will not go forward, then we will. We, the women, will. I shall call upon my fellow women. We will fight the white men. We will fight till the last of us falls in the battlefields." She collected men to form a force with which to attack the British and retrieve the exiled king.[1] The enraged populace produced a large number of volunteers. As Hodgson's deputy, Captain Cecil Armitage, searched for the stool in a nearby brush, his force was surrounded and ambushed, only a sudden rainstorm allowing the survivors to retreat to the British offices in Kumasi. The offices were then fortified into a small stockade, 50 yards (46 m) square with 12 feet (3.7 m) loopholed high stone walls and firing turrets at each corner,[2] that housed 18 Europeans, dozens of mixed-race colonial administrators, and 500 Nigerian Hausas with six small field guns and four Maxim guns. The British detained several high ranking leaders in the fort.[2] The Ashanti, aware that they were unprepared for storming the fort settled into a long siege, only making one assault on the position on 29 April that was unsuccessful. The Ashanti then continued to snipe at the defenders, cut the telegraph wires, blockade food supplies, and attack relief columns. Blocking all roads leading to the town with 21 log barricades six feet high with loopholes to fire through, hundreds of yards long and so solid they would be impervious to artillery fire.[2]

As supplies ran low and disease took its toll on the defenders, another rescue party of 700 arrived in June. Recognising that it was necessary to escape from the trap and to preserve the remaining food for the wounded and sick, some of the healthier men along with Hodgson, his wife and over a hundred of the Hausas made a break on 23 June, meeting up with the rescue force they were evacuated.[2] 12,000 Ashanti abrade (warriors) were summoned to attack the escapees, who gained a lead on the long road back to the Crown Colony, thus avoiding the main body of the Abrade. Days later the few survivors of the abrade assault took a ship for Accra, receiving all available medical attention.

The rescue column

As Hodgson arrived at the coast, a rescue force of 1,000 men assembled from various British units and police forces stationed across West Africa and under the command of Major James Willcocks had set out from Accra. On the march Willcocks's men had been repulsed from several well-defended forts belonging to groups allied with the Ashanti — most notably the stockade at Kokofu, where they had suffered heavy casualties. During the march Willcocks was faced with constant trials of skirmishing with an enemy in his own element while maintaining his supply route in the face of an opposing force utilizing unconventional warfare. In early July, his force arrived at Beckwai and prepared for the final assault on Kumasi, which began on the morning of 14 July 1900. Using a force led by Yoruba warriors from Nigeria serving in the Frontier Force, Willcocks drove in four heavily guarded stockades, finally relieving the fort on the evening of the fifteenth, when the inhabitants were just two days from surrender.

In September, after spending the summer recuperating and tending to the sick and wounded in captured Kumasi, Willcocks sent out flying columns to the neighbouring regions that had supported the uprising. His troops defeated an Ashanti force in a skirmish at Obassa on the 30 September and also succeeded in destroying the fort and town at Kokofu where he had been previously repulsed, using Nigerian levies to hunt Ashanti soldiers. Ashanti defenders would usually exit the engagement quickly after a stiff initial assault. Following the storming of the town, Captain Charles John Melliss was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery in the attack.

Aftermath

Kumasi was annexed into the British empire; however, the Ashanti still largely governed themselves. They gave little or no deference to colonial authorities. The Ashanti were successful in their pre-war goal to protect the Golden Stool. But, the following year, the British arrested numerous chiefs, including the Queen Mother of Ejisu, Yaa Asantewaa, and exiled them to the Seychelles for 25 years. In that 25-year period many of them died, including Yaa Asantewaa herself in 1921. Kumasi City retains a memorial to this war and several large colonial residences. Ashanti and the former Gold Coast eventually became part of Ghana.

The war cost the British and their allies approximately 1,000 fatalities in total; however, the Ashanti casualties are not known for certain.[4] The British never did capture the Golden Stool; it was hidden deep in the forests for the duration of the war. The British continued to seek it until 1920.[4] Shortly after this, it was accidentally uncovered by a team of labourers. They took the golden ornaments that adorned the stool, which made it powerless in the eyes of the Ashanti. An Ashanti court sentenced the labourers to death for their desecration, but British officials intervened, and arranged for their exile instead.

Return of the King Prempeh I to Ashanti

In 1924, the King was allowed to return. "Thousands of people, white and black, flocked down to the beach to welcome him. They were sorely disappointed when the news flashed through that Nana Prempeh was not to be seen by anyone, and that he was to land at 5:30 pm and proceed straight away to Kumasi by a special train. Twenty minutes after the arrival of the train, a beautiful car brought Nana Prempeh into the midst of the assembly. It was difficult for us to realise even yet that he had arrived. A charming aristocratic-looking person in a black long suit with a fashionable black hat held up his hand to the cheers of the crowd. That noble figure was Nana Prempeh."[5]

See also

References

- Footnotes

- 1 2 "Asante". BBC worldservice.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Robert B. Edgerton. The Fall of the Asante Empire: The Hundred-Year War For Africa's Gold Coast. ISBN 9781451603736.

- ↑ Fred M. Agyemang (1993). Accused in the Gold Coast. Waterville Publishing House. p. 84. ISBN 9789964502362. (The quoted text apparently does not appear in the 1972 first edition from Ghana Publishing House.)

- 1 2 Myles Osborne and Susan Kingsley Kent (2015). Africans and Britons in the age of empires, 1660–1980. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group (London). ISBN 9780415737524. OCLC 892700097.

- ↑ Extract from the Gold Coast Leader newspaper, 27 December 1924.

- Bibliography

- "The Yaa Asantewaa War of Independence Podcast".

- A. Adu Boahen. Yaa Asantewaa and the Asante-british War of 1900-1. ISBN 978-9988550998.

- "Yaa Asantewaa Profile", GhanaWeb

- "Yaa Asantewaa's War". WebCite

- http://www.uiowa.edu/~africart/toc/history/giblinstate.html

- "The Golden Stool".

- "The story of Africa – West African Kingdoms", BBC World Service.

- Hernon, Ian Britain's Forgotten Wars, 2002 ( ISBN 0-7509-3162-0)

- Lewin, J Asante before the British: The Prempean Years 1875-1900