Archosauriformes

| Archosauriformes | |

|---|---|

| |

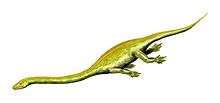

| Life restoration of a Proterosuchus fergusi | |

| |

| American alligator (A. mississippiensis) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Crocopoda |

| Clade: | Archosauriformes Gauthier, 1986 |

| Subgroups[1] | |

| |

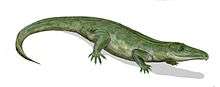

Archosauriformes (Greek for 'ruling lizards', and Latin for 'form') is a clade of diapsid reptiles that developed from archosauromorph ancestors some time in the Late Permian (roughly 250 million years ago). It was defined by Jacques Gauthier (1994) as the clade stemming from the last common ancestor of Proterosuchidae and Archosauria;[3] Phil Senter (2005) defined it as the most exclusive clade containing Proterosuchus and Archosauria.[4] These reptiles, which include members of the family Proterosuchidae and more advanced forms, were originally superficially crocodile-like predatory semi-aquatic animals about 1.5 meters (5 ft) long, with a sprawling elbows-out stance and long snouts. Unlike the bulk of their therapsid contemporaries, the proterosuchids survived the catastrophe at the end of the Permian, perhaps because they were opportunistic scavengers or because they could retreat into water to find respite from an overheated climate. Any such scenarios are hypothetical; what is clearer is that these animals were highly successful in their new environment, and evolved quickly. Within a few million years at the opening of the Triassic, the proterosuchids had given rise to the Erythrosuchidae (the first sauropsids to totally dominate their environment), which in turn were the ancestors of the small agile Euparkeriidae, from which a number of successfully more advanced families – the archosaurs proper – evolved rapidly to fill empty ecological niches in the devastated global system. The Archosauria includes crocodylians, birds, and their extinct relatives. The archosaurs were the only members of the Archosauriformes which survived the late Triassic extinction.[5]

Pre-Euparkeria Archosauriformes have previously been included in the suborder Proterosuchia of the order Thecodontia. Under the cladistic methodology, Proterosuchia has been rejected as a paraphyletic assemblage, and the pre-archosaurian taxa are simply considered as basal Archosauriformes.

Relationships

Below is a cladogram from Nesbitt (2011):[6]

| Archosauriformes |

*Note: Phytosaurs were previously placed within Pseudosuchia, or crocodile-line archosaurs. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Below is a cladogram from Sengupta et al. (2017),[7] based on an updated version of Ezcurra (2016)[1] that reexamined all historical members of the "Proterosuchia" (a polyphyletic historical group including proterosuchids and erythrosuchids). The placement of fragmentary taxa that had to be removed to increase tree resolution are indicated by dashed lines (in the most derived position that they can be confidently assigned to). Taxa that are nomina dubia are indicated by the note "dubium". Bold terminal taxa are collapsed.[1]

| Crocopoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sources

- Gauthier, J. A. (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". In Padian, K. The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. 8. California Academy of Sciences. pp. 1–55. ISBN 0-940228-14-9.

- Gauthier, J. A.; Kluge, A. G.; Rowe, T. (June 1988). "Amniote phylogeny and the importance of fossils". Cladistics. John Wiley & Sons. 4 (2): 105–209. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1988.tb00514.x.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Ezcurra, M.D. (2016). The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms. PeerJ, e1778

- ↑ Sookias, R. B.; Sullivan, C.; Liu, J.; Butler, R. J. (2014). "Systematics of putative euparkeriids (Diapsida: Archosauriformes) from the Triassic of China". PeerJ. 2: e658. doi:10.7717/peerj.658. PMC 4250070. PMID 25469319.

- ↑ Gauthier J. A. (1994): The diversification of the amniotes. In: D. R. Prothero and R. M. Schoch (ed.) Major Features of Vertebrate Evolution: 129-159. Knoxville, Tennessee: The Paleontological Society.

- ↑ Phil Senter (2005). "Phylogenetic taxonomy and the names of the major archosaurian (Reptilia) clades". PaleoBios. 25 (2): 1–7.

- ↑ Anatomy, Phylogeny and Palaeobiology of Early Archosaurs and Their Kin

- ↑ Nesbitt, S.J. (2011). "The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292. doi:10.1206/352.1.

- ↑ Sengupta, S.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Bandyopadhyay, S. (2017). "A new horned and long-necked herbivorous stem-archosaur from the Middle Triassic of India". Scientific Reports. 7.