Archaeology of Oman

The present-day Sultanate of Oman lies in the south-eastern Arabian Peninsula. There are different definitions for Oman: While traditional Oman also includes the present-day United Arab Emirates, its prehistoric remains differ in some respects from the more specifically defined 'Oman proper' which corresponds roughly with the present-day central provinces of the Sultanate. In the north, the Oman Peninsula is more specific, and juts into the Gulf of Hormuz. The archaeology of southern Oman Ẓafār develops separately from that of central and northern Oman.

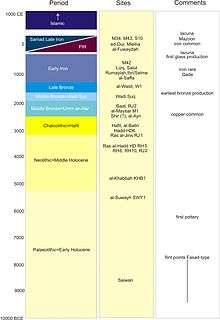

Different ages are reflected in typological assemblages, Old Stone Age, New Stone Age, Copper Age, Bronze Age, Early Iron Age, Late Iron Age, that is Samad Period, so-called late pre-Islamic culture and the Age of Islam. What is referred to as a period is inferred from a regularly recurring assemblages of artefacts. Some specialists equate periods with cultures. The names of the ages are conventional and are difficult to fix in terms of absolute years. Aside from this the development is highly regional. The archaeological assemblages of the South Province Dhofar differ completely from those of the central part of the country. A key barometer of industrial activity is the amount of copper production, as known from smelting refuse (slag) and metallic artefacts.

Archaeologically speaking, differences increase between the area of the present-day U.A.E. and the Sultanate particularly toward the end of the Early Iron Age, conditioned locally by the different geographical situations. The amount of moisture dictates the amount and place of agriculture and population that are sustainable. A variety of subsistence strategies exploit the available resources. Since archaeological field work began in the Sultanate in the early 1970s, numerous teams have worked in the Sultanate.

Except for the Islamic period, what they all share is that they are known primarily from cemeteries, tombs and grave goods. The absolute dates for the different periods are still under study and it is difficult to assign years to the Late Iron Age of central and southern Oman. Even major monuments have been dated variously, spanning millennia. The meanings of major concepts such as Arab are controversial.

Palaeolithic

Old Stone Age: Looking to archaeogenetic research, the emerging picture indicates a major dispersal of our species out of Africa between 50 and 100 thousand years ago.[1] Despite the numerous studies proposing early human population expansions from Africa into Arabia during the Late Pleistocene, no archaeological sites have yet been discovered in Arabia that resemble a specific African industry, which would indicate demographic exchange across the Red Sea.[2] Known primarily from survey finds. Lithic findspots near Ra's al-Jins. Main sites include Saiwan-Ghunaim in the Barr al-Hikman.[3]

Neolithic

The first agricultural settlements. Known from a variety of sites, most of which lie on the coast. It co-incides with the beginning of the Holocene and sees the advent of a food producing economy as opposed to a hunting and gathering based one. The picture of the Neolithic of south-eastern Arabia (ca. 8000-4000 BC) has become increasingly detailed since research began in 1977. Like other periods here, the Neolithic still lacks a reliable chronological framework[4]. Key sites include Ra's al-Ḥamrāʾ, Ra's al-Ḥadd, Suwayh and Ra's Dan, Maṣīrah, not to omit newly discovered ones in Ẓafār. [5].

Copper Age

Copper Age, 3500-2300 BC Hafit period: Known originally from a cemetery site on the Jebel Hafit in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Like the following Bronze Age periods, sites with characteristic finds are distributed over the UAE and Sultanate. Typically burial cairns lie on top of hill crests. Copies and pottery imports from southern Mesopotamia occur. Such finds have been documented on the eastern coast of the Sultanate near Ra's al-Hadd, especially HD-6 and Ra's al-Jinz. Diagnostic pottery of Jemdet Nasr type has survived in some tombs. The smelting of oxidic copper ores begins, as perhaps at al-Batina.[6] Such ores would leave little slag and the process did not require special conditions. Already at this time there is textual evidence from Sumer for international trade in copper and other commodities, probably from Oman.[7]

Bronze Age

Bronze Age 3300 - 1200 BC: The Umm al-Nar and Wadi Suq Periods (2600 - 1300 BC). Examples may be found at numerous funerary sites, for example on the island Umm an-Nar and in the Wadi Suq. Typical of this period are wheel-turned painted vessels which distinguish these two periods. During the Bronze Age, metal production increased considerably in relation to that of the preceding Hafit Period, with several specimens of plano-convex copper ingots weighing 1–2kg found. Tower tombs, such as those at Shir (22°48′55″N 59°03′18″E / 22.815315°N 59.054990°E), can only be approximately dated, and may date to the Hafit or Umm an-Nar Periods.[8] During the Umm an-Nar Period, large communal, free-standing tombs contain numerous interments. Other tombs are smaller and may contain one or a few interments.

In the 1980s, important archaeological discoveries have been made at Ras al-Jinz, located at the easternmost point of the Arabian Peninsula, demonstrating maritime Indus Valley connections with Oman, and the Middle East in general.[9][10]

In Ẓafār weapons came to light in a confirmed grave context datable to the 3rd millennium BC[11].

Late Bronze Age

Late Bronze Age 1500 - 1300 BC: Following the Wadi Suq Period, this period follows. It is represented by both grave and settlement finds[12]

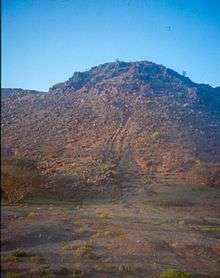

Early Iron Age

1300 - 300 BC: Known from different cemetery and copper producing sites especially the fort on the Jebel Radhania, Lizq and the fort at Salut. This period is known from some 142 archaeological sites (or 161, depending on how one counts) located in the eastern part of the United Arab Emirates as well as the Central and northern parts of the Sultanate of Oman. The nomenclature for the period is more controversial than the actual chronology. One scholar in particular offered the most concrete argumentation for a gradual transition as a model from the Early to Late Iron Ages at certain sites in Central Oman[13].

Usually hand-made, hard-fired pottery. The pottery from the Lizq fort is most similar to that from the latest Early Iron Age sites at al-Moyassar and Samad al-Shan. In terms of pottery chronology, its beginnings there are obscure.[14]

The dead are interred in existing subterranean tombs or in new hut-like free-standing ones. All of thetombs of given group may be oriented in one direction. However, different groups deviate from each other. The inhabitants must have considered their society to be a safe one since they built such visible and vulnerable free-standing tombs with poor chances of survival and as a ready source of building materials have rapidly disappeared since 1980. No intact tomb of this period has ever been excavated.

The number of copper-alloy artefacts reaches a peak at this time which will only be surpassed around the 9th century AD. The reason is that the technology to roast the more abundant sulphidic copper ore was developed. A hoard of over 500 copper alloy artefacts at ʿIbrī/Selme gives a fair idea of the production at this time.[15] In 2012 another copper and iron metal-working workshop came to light first reported incorrectly as at 'al-Saffah', 'as-Safa' (السفة), actually al-Ṣafāʾ (الصفا) after a site some 40 km to the south-west al-Saffah, Oman. In reality this site is known as ʿUqdat al-Bakrah (عقدة البكرة). More than 400 metallic artefacts often found close shape correspondences with those from ʿIbrī/Selme.

An important connection with the outside world comes to bear in a cuneiform inscription (640 BCE) of the Neo-Assyrian king Assurbanipal. He mentions emisaries sent by a king by the name of Pade who resides in Izki in the land of Qade[16]. It yielded to date nearly 700 metallic artefacts. The introduction of the falaj for irrigation coincides with the rapid growth of date as a main crop. The chronology for this age resembles but also differs from the better known one of the present-day U.A.E. During this Iron Age paradoxically in Oman iron artefacts are rather rare, although in neighbouring Iran after 1200 BC iron weapons are characteristic. Pre-Arabic place-names such as Bidbid, Izki, Ṣuḥar and ʿIbri probably represent the bare remnants of the language and speakers of this and the next age.

Samad Late Iron Age

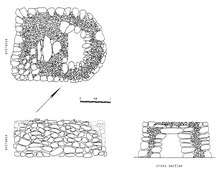

At the end of the Early Iron Age, after some 200-300 years without absolutely dated archaeological contexts, in central Oman weak evidence exists for the Samad Late Iron Age from c. 100 BC to 300 AD, dated by means of a thermoluminescense dating and a few outside artefactual comparisons. The end date is even weaker than the beginning. This assemblage is known from 13 possible and 74 more certainly attributed archaeological sites in 30 localities. Evidence for a transition from the EIA is rare in Central Oman and the chronological situation is clearest at the multi-period site complex at al-Maysar (al-Moyassar): falaj water sites from the EIA, LIA and medieval periods survive to this day. Over the centuries, and especially recently, the water table dropped, so that the falaj floor had to be lowered to the height of the water table.[17]. This period witnesses a drastic reduction in population for reasons unknown. Perhaps the newcomers could not maintain the life-giving falaj system. Evident during this period also is a loss of copper producing technology.

Samad LIA sites scatter over an estimated 17,000 km2 bordered to the west in Izkī, to the north in the capital area, to the south Jaʿlān, and to the east at the coast[18]. It is absent in the Bāṭinah[19] and is limited basically to the Sharqīyah province. Defective radiocarbon dates found no acceptance. Samad al-Shan and smaller sites, such as al-Akhdhar, al-Amqat, Bawshar[20] and al-Bustan, are type-sites for this non-writing population, with mostly hand-made pottery, copper alloy and iron artefacts. Reoccurring pottery wares and shapes, small finds as well as a few grave structure types define the Samad Late Iron Age assemblage.[21].

Where the soil is deep enough, individual stone-built graves are sunk into the earth. Such classical Samad graves have a low wall on the roof near the north-western end perpendicular to the long axis. They contain flexed skeletons. The men usually are placed on the right side, the women usually on the left. The heads generally point toward the south-east.

Few fragmentary settlements (Mahaliya, al-Nejd, Nejd Madirah, Qaryat al-Saiḥ in Wadi Maḥram, Samad al-Shan sites S1, S7, ʿUmq al-Rabaḫ, Ṭīwī site TW2) have been documented.

No coins were struck locally, and to date only two examples have turned up in contexts together with Samad Late Iron Age pottery. While the northern part of traditional Oman had at least partly a currency economy, Central Oman did not.

In the LIA a few glazed pottery imports derive from the upper Gulf and southern Mesopotamia. One class of pottery, balsamaria are wheel-turned and also are common in the late Pre-Islamic Late Iron Age graves in both areas of Oman. Approximately 3/4 of the find inventories in Central Oman finds are attributable to the Samad assemblage, far fewer to the so-called période préislamique récente, and a few cannot be attributed to a definable find assemblage. Persian Achaemenid, Parthian and Sasanian dominance of Oman is firmly entrenched in the secondary literature. It is easy to criticise the integrity of the definition of the Samad assemblage.

Parthian and later Sasanian invaders from Iran dominated politically and militarily temporarily certain towns in Oman.[22]. But for logistical reasons it was possible to occupy only a few sites, as happened during later invasions[23]. Persian presence is inferred by a few place-names near or on the coast (e.g. al-Rustaq) and personal names in Izki[24]. It appears that at this time in Central Oman, so-called Modern South Arabian languages were spoken. For the Early Iron Age this is far less certain. From ±500 BC to ±500 AD or later, waves of migratory tribes from South and Central Arabia settle in south-eastern Arabia and Iran, as we know from oral historical sources. If so, then at least at first linguistically such populations were South Arabians and not Arabs. The tribal grounds of the Azd tribes in south-eastern Arabia of course are far larger and more diverse than the area of the Samad Late Iron Age sites. To judge from the Samad stone graves and from evidence about their diet, this was not Bedouin population, but rather consisted of farmers.

These tribes brought the South Arabian, later Arabic with them as far east as Khorasan in Iran. However, Omani Arabic has its own words and is not just an import from Central Arabia[25]. It is assumed that Classical Arabic arrived with the Arab diaspora and Islam in the 7th and 8th centuries CE, first to the centres. The occurrence in Arabia and the Red Sea littoral of ribbed amphorae manufactured in Aqaba/Ayla evidently in order to transport wine, shows the area just north of Aqaba to have been a fruitful agricultural area from 400 up to possibly 1000. On the other hand, D. Fleitmann has studied speliotherms from al-Hutha cave in central Oman and has gathered information for a series of megadroughts especially around 530. These may have afflicted the entire Peninsula.

non-Samad Late Iron Age

Several Late Iron Age sites do not link in terms of form and details of manufacture of their artefacts with the Samad characteristic assemblage. For example, the weapons are differently fashioned, as in one grave at Bawshar[26]. Curiously, some of the monuments previously described as megalithic[27], are now described as 'small stone monuments'[28]. The term megalith has been used and misused in a wide variety of meanings. Triliths differ from ones in Europe in size and shape. The most important example are triliths (Arab. ʿathfiya/ʿathāfy) - rowed groups of three stones perched together to form a steep pyramid. A fourth stone may lie horizontally on top. Triliths lie in wadis, the main habitation area of nomads[29]. The greatest concentration lies in the Ẓafār province and in eastern Yemen. Scholars have suggested a connection between the speakers of the Modern South Arabian Language, Mahra, and the triliths[30]. To judge from Mehra place-names and the triliths, Mahri speakers lived further to the north until Bedouin tribes pushed them into the south[31]. The triliths are the only find-category that central and southern Oman hold in common. A connection with Ṧḥahrī/Ǧibbāli is also plausible since triliths lie in areas in which today this language group still is actively spoken[32].

Pre-Islamic recent period:[33]. Known from different sites in the Sultanate, for example probably ʿAmlāʾ/Amlah, al-Fuwaydah. Such sites are largely contemporary with Late Iron Age of Samad in Central Oman, especially in the Sharqiyah. In the U.A.E. such show evidence of writing such as on coins. Regarding the relative chronology of the two there is considerable consensus. However, a difficulty in order to build a chronology lies in the lack of clear artefactual parallels between the Samad assemblage and that of these sites. At the partially excavated cemetery site of al-Fuwaydah the artefacts, especially pottery and metalwork, are more similar to contemporary ones from the U.A.E. than to those of Samad.[34].

Iron Age in Dhofar (Ẓafār)

Late Iron Age in Dhofar: Survey and a few excavations shed light on the archaeology of the South Province of the Sultanate[35]. The largest and best-known site is Khor Rori - a trading fort established by the Hadhramite kingdom in the 3rd century BC[36]. While this site shows a mixture of artefacts, many of which are of Old South Arabian type, the surrounding countryside reveals a melange of different kinds of artefacts. Khor Rori owes its existence to the trading of aromatics, in particular frankincense[37]. The type of sherd depicted was for many years considered to be Late Iron Age. Recent research re-dates to the medieval period. The Iron Age is divided into two different period, 'Iron Age A' (1300-300 BC) and 'Iron Age B' (325 BC-650 AD) [38].

Islamic Age

Very little archaeological evidence from the early Islamic Age exists. The earliest building structures which survive date to medieval times. With the coming of Islam and the diaspora of Arabian tribes, the Arabic language takes hold in Oman. Copper production reaches a record high to judge from the amount of slag which has survived from 150 known smelting sites[39]. With 100,000 tons of slag, Lasail (actually al-Azayl) in Wadi Jizzi is the largest smelting site in Oman [40].

Sources

- Michel Mouton, La péninsule d’Oman de la fin de l’âge du fer au début de la période sasanide (250 av. – 350 ap. JC), 1992, BAR International Series 1776, (printed 2008).

- Daniel T. Potts, The Persian Gulf in Antiquity, 2 vols., Oxford 1992

- Paul Yule, Cross-roads – Early and Late Iron Age South-eastern Arabia, Abhandlungen Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, vol. 30, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-447-10127-1, E-Book: ISBN 978-3-447-19287-3.

References

- ↑ Jeffrey I. Rose & Anthony E. Marks, “Out of Arabia” and the Middle-Upper Palaeolithic transition in the southern Levant, Quartär 61, 2014, 49-85.

- ↑ Jeffrey I. Rose et al., The Nubian Complex of Dhofar, Oman: An African Middle Stone Age Industry in Southern Arabia, Plos November 30, 2011 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028239 .

- ↑ Margaretha Uerpmann, Structuring the Late Stone Age of Southeastern Arabia, Arab. arch. epig. vol. 3, Issue 2, June 1992, 65–109; Serge Cleuziou & Maurizio Tosi, In the Shadow of the Ancestors (Muscat 2007) 19-31; Reto Jagher & Christine Pümpin, A New Approach to Central Omani Archaeology, Proc. Sem. Arabian Stud. 40, 2010, 185-200.

- ↑ Margarethe Uerpmann, Structuring the Late Stone Age of southeastern Arabia, Arab. Arch. Epig. 3, 1991, 65-109; Sophie Méry, Vincent Charpenthier, Neolithic material cultures of Oman and the Gulf seashores from 5500–4500 BCE, Arab. Arch. Epigraphy 24.1, 2013, 73-8

- ↑ P. Biagi, The Shell Middens of the Arabian Sea and Gulf: Maritime Connections in the Seventh Millennium BC, in: A.R. Ansary et al. (eds.), The City in the Arab World, Riyadh 2005, 7-16; Serge Cleuziou & Maurizio Tosi, In the Shadow of the Ancestors (Muscat 2007) 63-88

- ↑ Paul Yule & Gerd Weisgerber, Die 14. Deutsche Archäologische Oman-Expedition 1995, MDOG 128, 1996, 135–155+Beilage 1, ISSN 0342-118X, URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeumdok/volltexte/2010/577/

- ↑ . Gerd Weisgerber et al., Mehr als Kupfer in Oman, Anschnitt 33, 1981, 174‒7. ISSN 0003-5238

- ↑ Paul Yule & Gerd Weisgerber, The Tower Tombs at Shir, Eastern Ḥajar, Sultanate of Oman, Beiträge zur allgemeinen und vergleichenden Archäologie (BAVA) 18, 1998, 183–241, ISBN 3-8053-2518-5,

- ↑ Maurizio Tosi: Die Indus-Zivilisation jenseits des indischen Subkontinents, in: Vergessene Städte am Indus, Mainz am Rhein 1987, ISBN 3805309570, S. 132-133

- ↑ Story of Ras Al Jinz. Oman Information

- ↑ Paul Yule, A Prehistoric Grave Inventory from Aztaḥ, Ẓafār, in: P. Yule (ed.), Studies in the Archaeology of the Sultanate of Oman, Orient-Archäologie, vol. 2, Rahden/Westfalia, 1999, 91–6, {{ISBN 3-89646-632-1}}

- ↑ Christian Velde, Wadi Suq and Late Bronze Age in the Oman Peninsula, in Proceedings of the First Archaeological Conference on the U.A.E., London, 102–13; Paul Yule & Gerd Weisgerber, Al-Wāsiṭ Tomb W1 and other Sites, Materials for a Definition of the Second Half of the 2nd Millennium BCE, Anschnitt, 2015, 9‒108.

- ↑ Jürgen Schreiber, Transformationsprozesse in Oasensiedlungen Omans. Die vorislamische Zeit am Beispiel von Izki, Nizwa und dem Jebel Akhdar. Dissertation, Munich, 1977. URL http://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/7548/1/Schreiber_Juergen.pdf

- ↑ Stephan Kroll, The Early Iron Age Lizq Fort, Sultanate of Oman, translated and revised by P. Yule, Zeitschrift für die Kultur außereuropäischen Kulturen 5, 2013, 159–220, ISBN 978-3-89500-649-4

- ↑ Paul Yule & Gerd Weisgerber, The Metal Hoard from ʿIbrī(Arabic: عبري)-Selme, Sultanate of Oman. Prähistorische Bronzefunde xx7, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-07153-9.

- ↑ R. Borger, Beiträge zum Inschriftenwrk Assurbanipals, die Prismenklassen A, B,C=K, D, E, F, G, H, J und T sowie andere Inschriften, Wiesbaden, 1996, 28, 294

- ↑ Gerd Weisgerber, The Impact of the Dynamics of Qanats and Aflaj on Oases in Oman, Internationales Frontinus-Symposium: Wasserversorgung aus Qanaten-Qanate als Vorbilder im Tunnelbau, 2.-5. Oktober 2003, Luxemburg, Heft 26, 2003, 61–97, esp. 74–7 fig. 24–9.

- ↑ P. Yule‒C. Pariselle, Silver phiale said to be from al-Juba (al-Wusṭa Governorate) ‒ an archaeological puzzle, Arab. Arch. Epigraphy 27, 2016, 153.

- ↑ Ben Saunders, Archaeological Rescue Excavations on Packages 3 and 4 of the Batinah Expressway, Sultanate of Oman, British Foundation for the Study of Arabia monograph 18, Oxford, 2016.

- ↑ Nāṣir ʾal-Jahwarī wa- ʿAlī ʾal-Tījānī ʾal-Māḥī, juġrāfiyyat ʾal-mawqiʿ wa-ṯaqāfat ʾal-makān natāʾij ḥafriyyāt mawqiʿ Bawšar, Salṭanat ʿUmān, Adumatu 15, 2007, 7‒32

- ↑ Paul Yule, Die Gräberfelder in Samad al-Shan (Sultanat Oman) Materialien zu einer Kulturgeschichte. Orient-Archäologie 4, Rahden 2001, ISBN 3-89646-634-8 ; Paul Yule, Cross-roads – Early and Late Iron Age South-eastern Arabia, Abhandlungen Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, vol. 30, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-447-10127-1, pages 62-66.

- ↑ Paul Yule, Late Pre-Islamic Oman: The Inner Evidence – The Outside View, Hoffmann-Ruf–M. al-Salami, A. (eds.), Studies on Ibadism and Oman, Oman and Overseas, vol. 2, Hildesheim, 2013, 13–33, ISBN 978-3-487-14798-7.

- ↑ Heinz Halm, Der vordere Orient um 1200, Tübinger Atlas Des Vorderen Orients, sheet B VIII 1, Wiesbaden, 1985, Template:ISBN-13: 978-3882267372.

- ↑ John Wilkinson, The origins of the aflāj of Oman, Jour Om. Stud. 6.1, 1983, 182-3.

- ↑ C. Holes, A participial infix in the eastern Arabian dialects ‒ an ancient pre-conquest feature?, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 38, 2011, 77

- ↑ P. Yule, G. Costa, C. Philipps, Grave IIb, in: Paul Yule (ed.), Studies in the Archaeology of the Sultanate of Oman, Rahden, 1999, 22, 27 Fig. 5 ISBN 3-89646-632-1

- ↑ Walter Dostal, Zur Megalithenfrage in Südarabien, in Festschrift Werner Caskel..., Brill, Leiden, 1968, 53-61

- ↑ Abdalaziz Ja’afar bin ‘Aqil & Joy McCorriston, Prehistoric small scale monument types in Hadramawt (southern Arabia): convergences in ethnography, linguistics and archaeology, Antiquity 83, 2009, 602-18

- ↑ Cf. Jörg Janzen, Die Nomaden Dhofars/Sultanat Oman traditional Lebensformen im Wandel, Bamberg, 1980 ISSN 0344-6557

- ↑ Walter Dostal, Die Beduinen in Südarabien. Eine ethnologische Studie zur Entwicklung der Kamelhirtenkultur in Arabien, Vienna, 1967; Juris Zarins, The Land of Incense, Archaeological Work in the Governorate of Dhofar, Sultanate of Oman 1990–1995, Sultan Qaboos University Publications, Archaeology & Cultural Heritage Series, vol. 1, Muscat, 2001, 134-5 fig. 65 map; Paul Yule, Late Pre-Islamic Oman: The Inner Evidence – The Outside View, in: M. Hoffmann-Ruf–A. al-Salami (eds.), Studies on Ibadism and Oman, Oman and Overseas, vol. 2, Hildesheim, 2013, 13–33, ISBN 978-3-487-14798-7; Michael J. Harrower, Matthew J. Senn and Joy McCorriston, Tombs, triliths and oases: spatial analysis of the Arabian human social dynamics (AHSD) project, archaeological survey 2009-2010, Journal Oman Stud. 18, 2014, 145-151 ISSN 0378-8180

- ↑ Dostal 1967, 184-8; W. Müller, Mahra, Encyclopedia of Islam, v. 6, 1991, 82

- ↑ Ali Aḥmad Maḥāsh al-Shaḥrī, Grave types and "triliths" in Dhofar, Arab. Archaeol. Epigraphy 2, 1991, 190-193 ISSN 0905-7196; idem, kayfa btadaynt wa-kayfa rtaqaynā bi-l-ḥaḍāra l-ʾinsāniyya min šibh al-žazīra l-ʿarabiyya Ẓafār kitābātuhā wa-nuqušuhā l-qadīma ʾaṭ-ṭabʿūlā, Dubai 1994, pages 273-4 figs. 248-251; idem, The Language of Aad, Dubai 2000, 188-9 figs.

- ↑ Michel Mouton, La péninsule d’Oman de la fin de l’âge du fer au début de la période sasanide (250 av. – 350 ap. JC), BAR International Series 1776, 1992 (printed 2008) ISBN 978-1-4073-0264-5

- ↑ Paul Yule, ʿAmlah, al-Zahirah (Sultanat Oman) – späteisenzeitliche Gräberfelder 1997, in: Paul Yule (ed.), Studies in the Archaeology of the Sultanate of Oman, Orient-Archäologie 2, Rahden, 1999, 119–186 ISBN 3-89646-632-1

- ↑ Juris Zarins, The Land of Incense. Archaeological Work in the Governorate of Dhofar, Sultanate of Oman 1990-1995, Muscat 2001 [ISBN unspecified]

- ↑ A. Avanzini, A Port in Arabia between Rome and the Indian Ocean (3rd century BC – 5th century AD), Rome 2008, ISBN 978-88-8265-469-6

- ↑ W. W. Müller, Weihrauch, in: Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, vol. 15, Munich, 699-777

- ↑ Juris Zarins, The Land of Incense. Archaeological Work in the Governorate of Dhofar, Sultanate of Oman 1990-1995, Muscat 2001, 79-104[ISBN unspecified]

- ↑ Gerd Weisgerber, Die Suche nach dem altsumerischen Kupferland Makan, Das Altertum 37, 1991, 76-90.

- ↑ G. W. Goettler, N. Firth, C. C. Huston, A preöiminary discussion of ancient min ing in the Sultanate of Oman, Jour. Oman Stud. 2, 1976, 44; Gerd Weisgerber, Mehr als Kupfer in Oman, Der Anschnitt, 5-6, 1981, 184-5 fig. 7.