Aramac, Queensland

| Aramac Queensland | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Aramac War Memorial, 2011 | |||||||||||||||

Aramac | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 22°58′S 145°15′E / 22.967°S 145.250°ECoordinates: 22°58′S 145°15′E / 22.967°S 145.250°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 299 (2011 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1869 | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 4726 | ||||||||||||||

| Location |

| ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | Barcaldine Region | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Gregory | ||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Maranoa | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Aramac /ˈærəmæk/ is a small town and locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia.[2][3] In the 2011 census, Aramac had a population of 299 people.[1]

Geography

Aramac is located 68 kilometres (42 mi) north of Barcaldine, and 1,280 kilometres (800 mi) by road from the state capital, Brisbane. It is situated on Aramac Creek, which flows into the Thomson River 60 kilometres (37 mi) west of town.

The predominant industry is grazing. The town water for Aramac is supplied from two bores connecting into the Great Artesian Basin.

History

In the 1850s, pastoralist and future Premier of Queensland Robert Ramsey Mackenzie travelled through the area, which was on the traditional lands of the Iningai. He blazed a tree with the inscription 'R R Mac', which was later corrupted into the name of the town.[4] William Landsborough also explored the area in 1859. Pastoral occupation began in 1862 on the Bowen Downs station on Reedy Creek, north of Aramac, and the Aramac Station (1863).

In 1867 an employee of Aramac Station, John William Kingston, opened a bark-hut store at an outlying point on the Aramac Creek. Enlarged two years later to include a hotel (Kingston's Bazaar), Kingston's settlement was declared a town site in 1869 and surveyed as a town in 1875. It was the region's first town, and the centre of the first local-government division.[5]

The town was originally called Marathon. The name was changed to that of Aramac, after the station, when the survey was conducted in 1875.[6] Recollections of an 1878 visit to Aramac were published in the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin in 1933, describing the township as consisting of "neat weatherboard structures, painted, and comprising four stores, three hotels, and three butchers' shops, with a post office, bank, court house, and surgery",[7] and the surrounding countryside and as "one of the emporia of the West."[7]

"The place is known to so many by name only that the visitor feels himself travelled. Moreover, he has become, acquainted, however slightly, with the great western country, of which we have all heard so much. "He has been on its threshold, having traversed the desert, and beheld, not without surprise, broad rolling downs stretching away to the horizon, with an open landscape, sparsely mottled with trees, the whole presenting a vivid contrast to the dense scrub and scanty herbage of some of the more easterly districts. He has, in a word, seen an oasis In the 'Sahara' -one which, to him, has a beginning, but is boundless on the western side. Besides this, if the visit has been made during Show week, he has come more, fully to appreciate the great pastoral interest, as represented in the persons of men of intelligence and energy -the pioneers of colonisation, the promoters of commerce."[7]

Little is known about the original indigenous population, although there was a reported massacre of 25 local Aborigines at the nearby Mailman's Gorge.[8][9] This event remained largely unknown until the publication of North Queensland Pioneers in 1932. The author stated:

"The blacks were very bad in the ranges around Aramac in the early days and the murder of a travelling jeweller and his wife and child caused reprisals. Harried by the police, the offending tribe took refuge in the country of a hostile tribe, and this precipitated wholesale tribal warfare. To this day it is said the mountain caves yield skeletons, the result of this tribal war." [10]

An 1865 account said the death of a shepherd or a government employee at Stainburn Downs station, north-west of Aramac, led to a revenge attack by squatters. Three Europeans are supposed to have tracked 30 Aborigines to a cave at Mailman’s Gorge and shot them.[11] Aramac State School opened on 21 January 1878.[12] By 1901 the school was well established and received a very positive report from the School Inspector, Mr. Benbow, printed in The Western Champion.

"The discipline is kind, quietly firm, and sensible; the moral tone appears to be healthy; the school habits are very satisfactory; general behaviour is respectful and attentive; the class movements are quietly and effectively carried out, and very good order is maintained. Methods: The methods employed in teaching are generally intelligent and skillful; they are applied with skill and considerable energy; the amount of revision is sufficient. Progress: The progress made by the pupils may be regarded as good and sound. General condition: Everything considered the general condition of the school is highly satisfactory. Remarks: The two highest classes have been carefully and intelligently instructed, and the pupils of these classes have evidently been taught to think. The demeanor of the children during inspection was most pleasing."

Aramac was initially a major outback town. However, the railway line ran through Barcaldine to the south, taking away the trade. The local council built a spur line (tramway) from Barcaldine, which opened on 2 July 1913. The tramway operated until 31 December 1975. A tramway museum that opened in 1994, occupies the old goods sheds.[6]

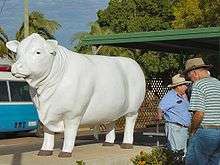

The white bull (pictured) was stolen by Henry 'Harry' Redford, otherwise known as Captain Starlight who duffed cattle from a property called Bowen Downs. The herd of cattle was driven overland to South Australia where some of the thieves were caught and tried.

Aramac Post Office opened on 1 March 1874,[13] a school in 1878 and a hospital[14] in 1879[15].

In 1914, Aramac developed thermal baths with its artesian water to promote itself as a health resort; however, it did not attract many invalids due to its isolated geographic location and the failure of the local government to promote the baths.[16]

In 1924 a branch of the Country Women's Association was formed in Aramac,[17] and by August that year were active, their efforts much appreciated in the town, and reported in the Western Champion. "Something new in entertainments was provided on Friday evening at the Shire Bail, when the Aramac branch of the Country Women's Association arranged a Euchre and Ping Pong tournament for us, with dance thrown in."[18]

.jpg)

At the 2006 census, Aramac had a population of 341.[19]

Facilities

Aramac has a visitor information centre, swimming pool located within the grounds of the Aramac Memorial Park in Gordon Street,[20] a town hall, showground and a pub. [21] There is no hospital, but nurse-led clinic facilities (Monday to Friday), ambulance services and 24-hours a day, seven days a week emergency on-call services. In 2016 the community had access to two doctors, with one staying overnight for two full days each week. The town is also serviced by the Royal Flying Doctor Service.[22]

Barcaldine Regional Council operates the Ollie Landers Community Library at 68 Gordon Street.[23][24]

Events

The annual Harry Redford Cattle Drive begins in Aramac and partly traces the 1870 footsteps of renowned cattle duffer Harry Redford, known as Captain Starlight,[5][25] who walked 1,000 head of cattle from Bowen Downs, north of Aramac, to South Australia. In 2015 and 2016 the drive was cancelled due to prolonged drought in the region.[26]

Heritage listings

Aramac has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- Boundary Street: Aramac Tramway Museum[27]

- Lodge Street: Aramac War Memorial[28]

- 69 Porter Street: Aramac State School[29]

The Aramac Tramway Museum was constructed as the Aramac Tramway Station in 1912-1913, funded by the Aramac Shire Council. It closed on 31 December 1975.[30]

The Aramac War Memorial was officially unveiled in April 1924, at a well attended public ceremony. The Last Post was played by Mr. Affoo, and the children were all given a bag of lollies at the end of the ceremony. Shire Chairman, E.W. Bowyer presided and gave the speech, as the Governor was unable to attend.[31]

This memorial was erected by the people of the Aramac Shire, as a modest tribute to the patriotism and loyalty of the men who enlisted to take part in the late deplorable European War. It will serve as an ineffaceable record to remind not only the rising generation but succeeding generations that Australians fought, bled, and died in the defence of their country.[31]

See also

References

- 1 2 Australian Bureau of Statistics (31 October 2012). "Aramac". 2011 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ "Aramac - town (entry 723)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "Aramac - locality (entry 47070)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ↑ Aramac, Queensland

- 1 2 "Aramac | Queensland Places". queenslandplaces.com.au. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- 1 2 Environmental Protection Agency (Queensland) (2002). Heritage Trails of the Queensland Outback. State of Queensland. p. 150. ISBN 0-7345-1040-3.

- 1 2 3 "ARAMAC TOWNSHIP". Morning Bulletin. Queensland, Australia. 28 September 1933. p. 13. Retrieved 27 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Walkabout - Aramac Archived 26 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Aramac - Queensland - Australia - Travel - smh.com.au". www.smh.com.au. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ↑ Black, J. (Jane); Queensland Country Women's Association (1930), North Queensland pioneers, Queensland Country Women's Association, retrieved 27 January 2017

- ↑ Ian D. Clark; Luise Hercus; Laura Kostanski (2014), Indigenous and minority placenames: Australian and international perspectives, ANU Press, retrieved 28 January 2017

- ↑ "Aramac State School". aramacss.eq.edu.au. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ↑ Premier Postal History. "Post Office List". Premier Postal Auctions. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ↑ "Aramac Primary Health Centre". Central West Health. 1 March 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ↑ "History of Aramac, QLD". Tilbury Lineage A journey through time. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ↑ Griggs, Peter (2013), 'Taking the waters': mineral springs, artesian bores and health tourism in Queensland, 1870-1950, Cambridge University Press, p. 164, retrieved 16 January 2017

- ↑ "Aramac Notes". The Longreach Leader. Queensland, Australia. 27 June 1924. p. 18. Retrieved 27 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Aramac Affairs". The Western Champion. Queensland, Australia. 30 August 1924. p. 14. Retrieved 27 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Aramac (L) (Urban Centre/Locality)". 2006 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ↑ Council, Barcaldine Regional. "Swimming Pools - Barcaldine Regional Council". www.barcaldinerc.qld.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "Barcaldine Regional Council". Barcaldine Regional Council. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ "Aramac Primary Health Care Centre | Queensland Health". 2017-01-28. Archived from the original on 2017-01-28. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "Aramac Library". State Library of Queensland. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ↑ "Libraries". Barcaldine Regional Council. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ↑ "Harry Redford Cattle Drive Map - ABC Rural - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". 2017-01-28. Archived from the original on 2017-01-28. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "Drought forces cancellation of iconic Harry Redford Cattle Drive for second year - ABC Rural - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". 2017-01-28. Archived from the original on 2017-01-28. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "Aramac Tramway Museum (entry 601172)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ "Aramac War Memorial (entry 600008)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ "Aramac State School (entry 602842)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ "Aramac Tramway Museum | Environment, land and water". environment.ehp.qld.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- 1 2 "Aramac Notes". The Longreach Leader (68). Queensland, Australia. 17 April 1924. p. 12. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aramac, Queensland. |