Appalachia (Mesozoic)

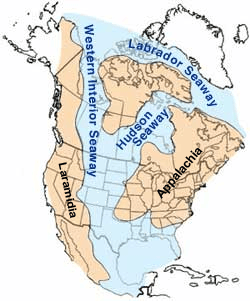

In the Mesozoic Era (252 to 66 million years ago) Appalachia, named for the Appalachian Mountains, was an island land mass separated from Laramidia to the west by the Western Interior Seaway. The seaway eventually shrank, divided across the Dakotas, and retreated towards the Gulf of Mexico and the Hudson Bay. This left the island masses joined in the continent of North America as the Rocky Mountains rose.[1]

From the Turonian to the end of the Campanian ages of the Late Cretaceous, Appalachia was separated from the rest of North America. As the Western Interior Seaway retreated in the Maastrichtian, Laramidia and Appalachia eventually connected.[2] Because of this, its fauna was isolated, and developed very differently from the tyrannosaur, ceratopsian, pachycephalosaur and ankylosaur dominated fauna of the western part of North America, known as "Laramidia". Due to numerous undiscovered fossiliferous deposits and due the fact that half of Appalachia's fossil formations being destroyed by the Pleistocene ice age,[3][4] little is known about Appalachia, with exception of plant life and the insects trapped in amber from New Jersey. Many of the various fossil formations not destroyed by the Pleistocene ice age still remain elusive to the field of paleontological study. In addition, due to a lack of interest in Appalachia, many fossils that have been found in Appalachia lie unstudied and remain in the inaccurate genera to which they were assigned in the days of E.D. Cope and O.C. Marsh. However, the area has seen a bit of a resurgence of interest due to several discoveries made in the past few years.[5][6][7][8][9][10] As mentioned earlier, not much is known about Appalachia, but some fossil sites, such as the Navesink Formation,[11] Ellisdale Fossil Site,[12] Mooreville Chalk Formation, Demopolis Chalk Formation, Black Creek Group and the Niobrara Formation,[13] together with ongoing research in the area,[14] have given us a better look into this forgotten world of paleontology.

Fauna

Dinosaurs

In Late Cretaceous North America, the dominant predators were the tyrannosaurs, huge predatory theropods with proportionately massive heads built for ripping flesh from their prey. Tyrannosaurs were the dominant predators in Appalachia too, but rather than the massive Tyrannosauridae, like Gorgosaurus, Albertosaurus and Lythronax,[15] which evolved around the same time that the Western Interior Seaway had fully separated Laramida from Appalachia, the smaller dryptosaurs were the top predators of Appalachia. Rather than developing the huge heads and massive bodies of their kin, dryptosaurs had more in common with the basal tyrannosaurs like Dilong and Eotyrannus, having long arms with three fingers,[16] and were not as large as the largest tyrannosaurids. Three genera of valid Appalachian tyrannosaurs are known, Dryptosaurus, Appalachiosaurus, and the recently discovered Teihivenator while other indeterminate fossils lie scattered throughout most of the southern United States like Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. These fossiled teeth possibly belong to a species of Appalachiosaurs or an undescribed species of a new tyrannosaur.[17][18] There is also the possibility of a fourth tyrannosaur known from Applachia known as Diplotomodon, but this is highly unlikely seeing how the genus is considered to be dubious. Various ornithomimid bones, such as Coelosaurus, have also been reported from Appalachia from Missouri, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and as far north in states like Maryland, New Jersey and Delaware, but it is now believed that some of these are the bones of juvenile dryptosaurs while others belong to various undescribed species of ornithomimids. The case of Arkansaurus is such an example of indeterminate fossils being discovered to be dating back to the Early Cretaceous. The dryptosaurs weren't the only predatory dinosaurs in Appalachia. Indeterminate dromaeosaurine fossils and teeth, most closely matching those of Saurornitholestes,[19] have also been unearthed in Appalachia as well; mostly in the southern states like Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia.[20] Finds from the Campanian Tar Heel Formation in North Carolina indicate that there may have been dromaeosaurids of considerable size; intermediate between genera such as Saurornitholestes and Dakotaraptor. Though known only from teeth, the discovery indicates large dromaeosaurids were part of Appalachia's fauna.[21] Along with the dromaeosauridae remains, tyrannosauroidea and possible ornithomimid remains have been unearthed in Missouri as well.[22]

Another common group, arguably the most wide spread species in the area,[23] of Appalachian dinosaurs were the Hadrosauroidea,[24] which is now considered to be their "ancestral homeland"; eventually making their way to Laramidia, Asia,[25][26][27][28][29] Europe,[30][31] South America[32] and Antarctica[33] where they diversified into the lambeosaurine and saurolophine dinosaurs, though some of the primitive hadrosaurs[34] were still present until the end of the Mesozoic.[35][36][37][38] While the fossil record shows a staggering variety of hadrosaur forms in Laramidia, hadrosaur remains for Appalachia show less diversity due to the relative uncommon number of fossil beds. However, many hadrosaurs are known from Appalachia, such as Claosaurus, Eotrachodon, Lophorhothon, Hypsibema crassicauda, Hypsibema missouriensis, and Hadrosaurus. These hadrosaurs from Appalachia seem to be closely related to the crestless hadrosaurs of Laramidia like Gryposaurus and Edmontosaurus, despite the fact that they are not considered to be saurolophines. Claosaurus is known from a specimen which floated into the Interior Seaway and was found in Kansas, might also be from Appalachia, since it was found closer to the Appalachia side of the seaway and is unknown from Western North America. Hadrosaur remains have even been found in Iowa, though in fragmentary remains,[39] Tennessee, most notably from the Coon Creek Formation.[40][41] Hypsibema crassicauda,[42] over fifty feet long, was one of the largest eastern hadrosaurs, outgrowing some of more derived western hadrosaurs like Lambeosaurus and Saurolophus. The genus likely took the environmental niche occupied by large sauropods in other areas, possibly grown to colossal sizes to that of Magnapaulia[43] and Shantungosaurus.[44] Hypsibema missouriensis, was another large species of hadrosaur, but it grew up to 45 to 49 feet, which wasn't as large as Hypsibema crassicauda. When it was first discovered in 1945, it was mistaken for a species of sauropod.[45] Hypsibema missouriensis, possibly even all of the other hadrosaurs living on Appalachia, had serrated teeth for chewing the vegetation in the area.[46] Indeterminate lambeosaurinae remains, mostly similar to Corythosaurus, have been reported from New Jersey's Navesink Formation and Nova Scotia, Canada. It cannot yet be explained how lambeosaurines might have reached Appalachia though some have theorized that a land bridge must have formed some time during the Campanian.[47]

The nodosaurids, a group of large, herbivorous armored dinosaurs resembling armadillos, are another testament to Appalachia's difference from Laramidia. During the early Cretaceous, the nodosaurids prospered and were one of the most wide spread dinosaurs throughout North America. However, by the latest Cretaceous, nodosaurids were scarce in western North America,[48] limited to forms like Edmontonia, Denversaurus and Panoplosaurus; perhaps due to competition from the ankylosauridae; though they did thrive in isolation, most notably in Appalachia, as mentioned earlier and in the case of Struthiosaurus,[49] Europe as well. Nodosaurid scutes have been commonly found in eastern North America, while fossil specimens are very rare. Often the findings are not diagnostic enough to identify the species, but the remains attest to a greater number of these armored dinosaurs in Appalachia. Multiple specimens have been unearthed in Kansas[50] in the Niobrara Formation, Alabama in Ripley Formation,[51] Mississippi, Delaware, Maryland and New Jersey, possibly belonging to a multitude of different species.[52] Five possible and best known examples of Appalachian nodosaurids, from both the early and late Cretaceous period, include Priconodon, Propanoplosaurus, Niobrarasaurus,[53][54] Silvisaurus[55] and possibly Hierosaurus,[56] though its validity is disputed. Just like the Claosaurus specimen, it is possible that the specimens of Niobrarasaurus, Silvisaurus and Hierosaurus floated into the Interior Seaway from the east, since these two species of nodosaurids were discovered in the famous chalk formations[57] of Kansas and are not known from any location from Western North America. Kansas was also a part of Appalachia when the other parts were covered by oceans, which were a part of the Western Interior Seaway.

While remains of the advanced ceratopsians, most notably the centrosaurines and chasmosaurines[58] which were very common in Laramidia during this timeperiod, where not found in Appalachia, the leptoceratopsids somehow managed to inhabit that location.[59] A Campanian-era leptoceratopsid ceratopsian has been found in the Tar Heel Formation, marking the first discovery of a ceratopsian dinosaur in the Appalachian zone. This specimen bears a uniquely long, slender and downcurved upper jaw, suggesting that it was an animal with a specialised feeding strategy, yet another example of speciation on an island environment.[60] Recently, a ceratopsian teeth were unearthed in Mississippi's Owl Creek Formation,[61] which have been dated to be 67 million years old.[62] While leptoceratopids remains, the few that have been discovered in recent years, have been unearthed in the southern part of Appalachia, they appear to be completely absent from the northern part of Appalachia, states like New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland. Suggesting the idea, proposed by paleontologist David R. Schwimmer, that there was a possible providence during the Late Cretaceous.[63]

Several bird remains are known from Appalachian sites, most of them sea birds like Hesperornithes, Ichthyornis, Enantiornithes like Halimornis and Ornithuraes like Apatornis and Iaceornis. Of particular interest are possible lithornithid remains in New Jersey, arguably one of the best records[64] for Cretaceous birds[65] as some specimens were preserved in the greensands[66] in the area,[67][68] which would represent a clear example of palaeognath Neornithes in the Late Cretaceous. However, this issue is still under debate.

Non-dinosaur herpetofauna

Through the Ellisdale Fossil Site, a good picture of Appalachia's non-dinosaurian fauna is present. Amidst lissamphibians, there is evidence for sirenids (including the large Habrosaurus), the batrachosauroidid salamander Parrisia, hylids, possible representatives of Eopelobates and Discoglossus, showing close similarities to European faunas, but aside from Habrosaurus (which is also found on Laramidia) there is a high degree of endemism, suggesting no interchanges with other landmasses throughout the Late Cretaceous.[69] There is also a high degree of endemism in regards for its reptilian fauna: among squamates, the teiid Prototeius is exclusive to the landmass, and native representatives of Iguanidae, Helodermatidae, and Necrosauridae. Amidst turtles, Adocus, Apalone, and Bothremys are well represented, the latter in particular more common in appalachian sites than laramidian ones. The five local crocodilian genera, Deinosuchus, Thoracosaurus,[70] Eothoracosaurus,[71]Leidyosuchus, Borealosuchus,[72] are well established in Laramidia as well, probably indicative of their ocean crossing capacities. Deinosuchus,[73] being one of the largest crocodilians of the fossil record,[74] was an apex predator that did prey on the dinosaurs[75] in the area, the same case applies for Laramidia as well,[76][77] despite the fact that the majority of its diet consisted of turtles[78][79] and sea turtles.[80] Pterosaur fossils, mostly similar to Pteranodon and Nyctosaurus, have been unearthed in Georgia,[81] Alabama[82] and Delaware.[83] On a similar note, azhdrachid remains have been reported in Tennessee.[84] No fossilized remains of snakes have been discovered in Appalachia during the Cretaceous period, only being found in Laramidia.[85]

Mammals

Several types of mammals[86] are also present on Ellisdale and in the both of the Carolinas.[87] The most common are ptilodontoidean multituberculates, such as Mesodma, Cimolodon and a massively sized species. The sheer diversity of species on the landmass, as well as the earlier appearance compared to other Late Cretaceous locales, suggests that ptilodontoideans evolved in Appalachia.[88][89] Metatherian are also known, including an alphadontid,[89] a stagodontid,[90] and an herpetotheriid.[91] Unlike ptilodontoideans, metatherians show a lesser degree of endemism, implying a degree of interchange with Laramidia and Europe.

See also

References

- ↑ Weishampel, David B.; Young, Luther (1996). Dinosaurs of the East Coast. Baltimore, MD.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ Stanley, Steven M. (1999). Earth System History. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 487–489. ISBN 0-7167-2882-6.

- ↑ Braun, Duane D. (September 1989). "Glacial and periglacial erosion of the Appalachians". Geomorphology. 2 (1–3): 233–256. Bibcode:1989Geomo...2..233B. doi:10.1016/0169-555X(89)90014-7.

- ↑ Pielou, E. C. (1 December 1992). After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press. p. 376.

- ↑ Uren, Adam. "Dinosaurs in Minnesota: Fossil claw found in Iron Range has scientists excited". Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Sawyer, Liz. "Fossil adds to evidence of dinosaurs in Minnesota". Star Tribune. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ "Fossil finds behind N.J. strip mall causing excitement". CBS Evening News. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ Anonymous. "Rare fossil of a horned dinosaur found from 'lost continent'". University of Bath News. University of Bath. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Anderson, Natali. "Eotrachodon orientalis: New Duck-Billed Dinosaur Species Discovered". Science News.com. Science News. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ Griffiths, Sarah. "Dinosaurs suffered from arthritis too! 70 million-year-old hadrosaur fossil shows its joints were covered in bony growths". Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Kennedy, William J.; Landman, Neil H.; Cobban, William Aubrey; Johnson, R.O. (13 December 2000). "Additions to the ammonite fauna of the Upper Cretaceous Navesink Formation of New Jersey. American Museum Novitates". American Museum Novitates: 31.

- ↑ Gallagher, W.B. (1997). When Dinosaurs Roamed New Jersey. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- ↑ "Oceans of Kansas".

- ↑ Brownstein, Chase (17 January 2018). "The biogeography and ecology of the Cretaceous non-avian dinosaurs of Appalachia". Palaeontologia Electronica. 21 (1.5a): 1–56. doi:10.26879/801. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Loewen, Mark A.; Irmis, Randall B.; Setrich, Joseph J. W.; J. Currie, Philip; D. Sampson, Scott (6 November 2013). "Tyrant Dinosaur Evolution Tracks the Rise and Fall of Late Cretaceous Oceans". PLOS One. 8 (11): 14. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...879420L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079420.

- ↑ Switek, Brian. "Dryptosaurus' Surprising Hands". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ↑ Chan-gyu, Yun (2017). "Teihivenator gen. nov., a new generic name for the Tyrannosauroid Dinosaur "Laelaps" macropus (Cope, 1868; preoccupied by Koch, 1836)". Journal of Zoological and Bioscience Research. 4.

- ↑ Carr, Thomas D; Williamson, Thomas E; Schwimmer, David R (2005). "A new genus and species of tyrannosauroid from the Late Cretaceous (Middle Campanian) Demopolis Formation of Alabama". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25: 119–43. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0119:ANGASO]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Kiernan,, Caitlin R.; Schwimmeri, David R. "First Record of a Velociraptorine Theropod (Tetanurae, Dromaeosauridae) from the Eastern Gulf Coastal United States". ResearchGate. Journal of the Delaware Valley Paleontological Society: 89–93. Retrieved 7 May 2004.

- ↑ Westfall, Aundrea. "Dromaeosaurs". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Brownstein, Chase (2018). "A giant dromaeosaurid from North Carolina". Cretaceous Research. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.07.006.

- ↑ Fix, Michael F. "Dinosauria and Associated Vertebrate Fauna of the Late Cretaceous Chronister Site of Southeast Missouri". Geological Society of America. Retrieved 1 April 2004.

- ↑ King Jr., David T. "Late Cretaceous Dinosaurs of the Southeastern United States". www.aubrun.edu. Auburn University Press. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Colbert, Edwin H. (1948). "A Hadrosaurian Dinosaur from New Jersey". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 100: 23–37. JSTOR 4064414.

- ↑ Godefroit, P.; Bolotsky, Y. L.; Lauters, P. (2012). Joger, Ulrich, ed. "A New Saurolophine Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Far Eastern Russia". PLoS ONE. 7 (5): e36849. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736849G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036849. PMC 3364265. PMID 22666331.

- ↑ Godefroit, Pascal; Bolotsky, Yuri; Alifanov, Vladimir (2003). "A remarkable hollow-crested hadrosaur from Russia: an Asian origin for lambeosaurines". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2 (2): 143–151. doi:10.1016/S1631-0683(03)00017-4.

- ↑ Godefroit, Pascal; Shuqin Zan; Liyong Jin (2000). "Charonosaurus jiayinensis n. g., n. sp., a lambeosaurine dinosaur from the Late Maastrichtian of northeastern China". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série IIA. 330 (12): 875–882. Bibcode:2000CRASE.330..875G. doi:10.1016/S1251-8050(00)00214-7.

- ↑ Bolotsky, Y.L. & Kurzanov, S.K. 1991. [The hadrosaurs of the Amur Region.] In: [Geology of the Pacific Ocean Border]. Blagoveschensk: Amur KNII. 94-103. [In Russian]

- ↑ Godefroit, P.; Bolotsky, Y. L.; Van Itterbeeck, J. (2004). "The lambeosaurine dinosaur Amurosaurus riabinini, from the Maastrichtian of Far Eastern Russia". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 49 (4): 585–618.

- ↑ Casanovas, M.L; Pereda-Suberbiola, X.; Santafé, J.V.; Weishampel, D.B. (1999). "First lambeosaurine hadrosaurid from Europe: palaeobiogeographical implications". Geological Magazine. 136 (2): 205–211. Bibcode:1999GeoM..136..205C. doi:10.1017/s0016756899002319.

- ↑ Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier; José Ignacio Canudo; Penélope Cruzado-Caballero; José Luis Barco; Nieves López-Martínez; Oriol Oms; José Ignacio Ruiz-Omeñaca (2009). "The last hadrosaurid dinosaurs of Europe: A new lambeosaurine from the Uppermost Cretaceous of Aren (Huesca, Spain)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 8 (6): 559–572. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2009.05.002.

- ↑ Rubén D. Juárez Valieri; José A. Haro; Lucas E. Fiorelli; Jorge O. Calvo (2010). "A new hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous) of Patagonia, Argentina" (PDF). Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales n.s. 11 (2): 217–231.

- ↑ Case, Judd A.; Martin, James E.; Chaney, Dan S.; Regurero, Marcelo; Marenssi, Sergio A.; Santillana, Sergio M.; Woodburne, Michael O. (25 September 2000). "The First Duck-Billed Dinosaur (Family Hadrosauridae) from Antarctica". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (3): 612–614. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0612:tfdbdf]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4524132.

- ↑ Dalla Vecchia, F. M. (2009). "Tethyshadros insularis, a new hadrosauroid dinosaur (Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Italy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1100–1116. doi:10.1671/039.029.0428.

- ↑ Lund, Eric K.; Gates, Terry A. (January 2006). "A Historical and Biogeographical Examination of Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs".

- ↑ Kaye, John M.; Russell, Dale. (1973). "The oldest record of hadrosaurian dinosaurs in North America". Journal of Paleontology: 91–93.

- ↑ "Research team identifies rare dinosaur from Appalachia". 21 January 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ Lull, Richard S.; Wright, Nelda E. (1942). "Hadrosaurian dinosaurs of North America". Geological Society of America. Geological Society of America Special Papers (40): 1–272.

- ↑ Witzke, Brain J. "Dinosaurs in Iowa". Iowa Geological Society. Iowa Department of Natural Resources, University of Iowa. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ Byran, Jonathan R.; Frederick, Daniel L.; Schwimmer, David R.; Siesser, William G. (July 1991). "First dinosaur record from Tennessee: a Campanian hadrosaur". Journal of Paleontology. 65 (4): 696–697. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ Markin, Walter L.; Gibson, Michael A. (3 November 2010). "Discovery of a Second Hadrosaur From the Late Cretaceous Coon Creek Formation, West Tennessee". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 42 (5): 631.

- ↑ Cope, E.D. (1869). "Remarks on Eschrichtius polyporus, Hypsibema crassicauda, Hadrosaurus tripos, and Polydectes biturgidus". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 21: 191–192.

- ↑ Albert, Prieto-Marquez; Luis, M. Chiappe; Shantanu, H. Joshi (12 June 2012). "The Lambeosaurine Dinosaur Magnapaulia laticaudus from the Late Cretaceous of Baja California, Northwestern Mexico". PLoS ONE. 7 (6): 29. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738207P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038207. PMC 3373519. PMID 22719869. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ Chase. "Antediluvian Beasts of the East: Hypsibema crassicauda". thetetanuraeguy.wordpress.com. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ↑ Gilmore, Charles W.; Stewart, Dan R. (January 1945). "A New Sauropod Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Missouri". Journal of Paleontology. 19 (1): 23–29. JSTOR 1299165.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Fossil Prep Lab!". Bollinger County Museum of Natural History.

- ↑ Chase. "A response to The Tetrapod Zoology Podcast #45: Why Lambeosaurines did, in fact, persist into the Maastrichtian". An Odyssey of Time. Anonymous. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ Bakker, Robert T. (1988). "Review of the Late Cretaceous nodosauroid Dinosauria: Denversaurus schlessmani, a new armor-plated dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of South Dakota, the last survivor of the nodosaurians, with comments on Stegosaur-Nodosaur relationships". Hunteria. 1 (3): 1–23.

- ↑ Garcia, G.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X. (2003). "A new species of Struthiosaurus (Dinosauria: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Villeveyrac (southern France)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (1): 156–165. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[156:ansosd]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ "Approximate location of Smoky Hill Chalk nodosaur remains". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Bruns, Michael E. "New Appalachian Armored Dinosaur Material (Nodosauridae, Ankylosauria) From the Maastrichtian Ripley Formation of Alabama". The Geological Society of America. The Geological Society of America. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Ebersole, Jun. "Nodosaur". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Everhart, Michael J.; Hamm, Shawn A. (January 2005). "A new nodosaur specimen (Dinosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 108 (1&2): 15–21. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2005)108[0015:ANNSDN]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth; Everhart, Michael J. (April 2007). "Skull of the ankylosaur Niobrarasaurus coleu (Ankylosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Coniacian) of western Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 110 (1 & 2): 1–9. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2007)110[1:SOTANC]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Eaton, T.H.; Jr (1960). "A new armored dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Kansas". The University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions: Vertebrata. 8: 1–24.

- ↑ Wieland, G. R (1909). "A new armored saurian from the Niobrara". American Journal of Science (159): 250–2. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-27.159.250.

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth; Dilkes, David; Weishampel, Dave (June 1995). "The Dinosaurs of the Niobrara Chalk Formation (Upper Cretaceous, Kansas)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 15 (2): 275–297. doi:10.1080/02724634.1995.10011230.

- ↑ "Amazing horned dinosaurs unearthed on 'lost continent'; New discoveries include bizarre beast with 15 horns". ScienceDaily. University of Utah. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ Anonymous. "A new Leptoceratopsid Ceratopsian From Campanian Cretaceous Appalachia". The Dragon's Tales. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ↑ Longrich, Nicholas R. (2016). "A ceratopsian dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of eastern North America, and implications for dinosaur biogeography". Cretaceous Research. 57: 199–207. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.08.004.

- ↑ Brantley, Mary Grace. "Paleontologists make big dinosaur discovery in Mississippi". MSNewsNow. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Fleet, Micah. "Rare dinosaur tooth found in Mississippi". www.wapt.com. 16 WAPT News. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ David R., Schwimmer. "Was There a Southeastern Dinosaur Province in the Late Cretaceous?". 1 April 2016. Geological Society of America. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Olson, Storrs L.; Parris, David C. (1987). "The Cretaceous Birds of New Jersey" (PDF). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology. 63: 1–25.

- ↑ Wetmore, Alexander (April 1930). "The Age of the Supposed Cretaceous Birds from New Jersey". The Auk. 47 (2): 186–188. doi:10.2307/4075921. JSTOR 4075921.

- ↑ Baird, Donald (April 1967). "Age of Fossil Birds from the Greensands of New Jersey". The Auk. 84 (2): 260–262. doi:10.2307/4083191. JSTOR 4083191.

- ↑ Palaeogene Fossil Birds

- ↑ A lithornithid (Aves: Palaeognathae) from the Paleocene (Tiffanian) of southern California

- ↑ Le Loeuff, J., 1991, The Campano-Maastrichtian vertebrate faunas of southern Europe and their relationship with other faunas in the world; paleobiogeographic implications. Cretaceous Res., 12(2), pp:93–114.

- ↑ Troxell, Edward L. (September 1925). "Thoracosaurus, A Cretaceous Crocodile". American Journal of Science. 5 (10): 219–233. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ Brochu, Christopher A. (5 January 2004). "A new Late Cretaceous gavialoid crocodylian from eastern North America and the phylogenetic relationships of thoracosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (3): 610–633. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0610:ANLCGC]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Brochu, Christopher A.; Parris, David C.; Grandstaff, Barbara Smith; Denton Jr., Robert K.; Gallagher, William B. (12 January 2012). "A new species of Borealosuchus (Crocodyliformes, Eusuchia) from the Late Cretaceous–early Paleogene of New Jersey". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (1): 105–116. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.633585.

- ↑ Schwimmer, David R. (12 June 2002). King of the Crocodylians: The Paleobiology of Deinosuchus. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. p. 240.

- ↑ Erickson, Gregory M.; Brochu, Christopher A. (18 June 1999). "How the 'terror crocodile' grew so big". Nature. 398 (6724): 205–206. Bibcode:1999Natur.398..205E. doi:10.1038/18343.

- ↑ Handwerk, Brain. "Feces, Bite Marks Flesh Out Giant Dino-Eating Crocs". National Geographic News. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ↑ RIVERA-SYLVA, Héctor E.; FREY, Eberhard; GUZMÁN-GUTIÉRREZ, José Rubén (2009). "Evidence of predation on the vertebra of a hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) of Coahuila, Mexico". Carnets de Géologie: 1–7.

- ↑ Rivera-Sylva, Hector E.; W.E. Hone, David; Dodson, Peter (2012). "Bite marks of a large theropod on an hadrosaur limb bone from Coahuila, Mexico" (PDF). 64 (1): 157–161.

- ↑ "Illustration of the hypothetical Deinosuchus-on-pleurodire bite, based on the position of typical bite marks. Wide gape biting would allowthe posterior teeth to do most of the crushing, without putting the sharperanterior teeth in danger of fracture. With this bite pattern, there would alsobe numerous marks on turtle neurals and approximately equal numbers ofcarapace and plastron bite traces. In addition, various regions of the turtleshell would receive varying pressures and depth of bite marks. Drawing byRon Hirzel, reproduced from Schwimmer (2002)".

- ↑ Milan, J; Lucas, Spencer G.; Lockley, M G; Schwimmer, David R. (January 2010). "Bite Marks of the Giant Crocodylian Deinosuchus on Late Cretaceous (Campanian) Bones".

- ↑ Harrell, Samantha D.; Schwimmer, David R. (2010). "Coprolites of Deinosuchus and other crocodylians from the Upper Cretaceous of western Georgia, USA": 1–7.

- ↑ Schwimmer, David R.; Padian, Kevin; Woodhead, Alfred B. "First Pterosaur Records from Georgia: Open Marine Facies, Eutaw Formation (Santonian)". 59. Journal of Paleontology: 674–676. JSTOR 1304987.

- ↑ Westfall, Aundrea. "Pterosaurs". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ Bairid, Donald; Galton, Peter M. "Pterosaur Bones from the Upper Cretaceous of Delaware". 1. Journal of Paleontology: 67–71. JSTOR 4522837.

- ↑ Gibson, Michael A. "Review of Vertebrate Diversity n the Coon Creek Formation Lagerstätte (Late Cretaceous) of Western Tennessee". Geological Society of America. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ↑ Holman, J. Alan (22 May 2000). Fossil Snakes of North America: Origin, Evolution, Distribution, Paleoecology. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 376.

- ↑ Baird, D.; Krause, D.W. (1 May 1979). "Late Cretaceous mammals east of the North American Western Interior Seaway". Journal of Paleontology. 53 (3). Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Denton Jr., Robert K. "Late Cretaceous Mammals of the Carolinas". gsa.confex.com. The Geological Society of America. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Late Cretaceous Multituberculates of the Carolinas: My...What Big Teeth You Have!

- 1 2 Grandstaff, B. S.; Parris, D. C.; Denton Jr, R. K.; Gallagher, W. B. (1992). "Alphadon (Marsupialia) and Multituberculata (Allotheria) in the Cretaceous of eastern North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 12 (2): 217–222. doi:10.1080/02724634.1992.10011450.

- ↑ Denton, R. K. Jr., & O’Neill, R. C., 2010, A New Stagodontid Metatherian from the Campanian of New Jersey and its implications for a lack of east-west dispersal routes in the Late Cretaceous of North America. Jour. Vert. Paleo. 30(3) supp.

- ↑ Martin, JE; Case, JA; Jagt, JWM; Schulp, AS; Mulder, EWA (2005). "A new European marsupial indicates a Late Cretaceous high latitude dispersal route". Mammal. Evol. 12 (3–4): 495–511. doi:10.1007/s10914-005-7330-x.