An Jung-geun

| Ahn Jung-Geun 안중근 | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Born |

2 September 1879 Haeju-bu, Hwanghaedo, Joseon (now Haeju, Hwanghae, North Korea) |

| Died |

26 March 1910 (aged 30) Ryojun, Kwantung Leased Territory, Empire of Japan (now Lüshunkou, China) |

| Known for | Assassinating Itō Hirobumi in 1909 |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 안중근 |

| Hanja | 安重根 |

| Revised Romanization | An Jung-geun |

| McCune–Reischauer | An Chunggŭn |

An Jung-geun (Korean pronunciation: [andʑuŋɡɯn]; September 2, 1879 – March 26, 1910; Baptismal name: Thomas) was a Korean-independence activist,[1][2][3] nationalist,[4][5] and pan-Asianist.[6][7]

On October 26, 1909, he assassinated Itō Hirobumi, a four-time Prime Minister of Japan and former Resident-General of Korea, following the signing of the Eulsa Treaty, with Korea on the verge of annexation by Japan.[8] Ahn was posthumously awarded the Order of Merit for National Foundation in 1962 by the South Korean government, the most prestigious civil decoration in the Republic of Korea, for his efforts for Korean independence.[9]

Biography

Early accounts

Ahn was born on September 2, 1879, in Haeju, Hwanghae-do, the first son of Ahn Tae-Hun (안태훈; 安泰勳) and Jo Maria (조성녀; 趙姓女), of the family of the Sunheung Ahn (순흥안씨; 順興安氏) lineage. His childhood name was Ahn Eung-chil (안응칠; 安應七; [anɯŋtɕʰil]). As a boy, he learned Chinese literature and Western sciences, but was more interested in martial arts and marksmanship. Kim Gu (김구; 金九), future leader of the Korean independence movement who had taken refuge in Ahn Tae-Hun's house at the time, wrote that young Ahn Jung-Geun was an excellent marksman, liked to read books, and had strong charisma.[10]

At the age of 16, Ahn entered the Catholic Church with his father, where he received his baptismal name "Thomas" (토마스), and learned French. While fleeing from the Japanese, Ahn took refuge with a French priest of the Catholic Church in Korea named Wilhelm (Korean name, Hong Seok-ku; 홍석구; 洪錫九) who baptized and hid him in his church for several months. The priest encouraged Ahn to read the Bible and had a series of discussions with him. He maintained his belief in Catholicism until his death, going to the point of even asking his son to become a priest in his last letter to his wife.[11]

At the age of 25, he started a coal business, but devoted himself to education of Korean people after the Eulsa Treaty by establishing private schools in northwestern regions of Korea. He also participated in the National Debt Repayment Movement. In 1907 he exiled himself to Vladivostok to join in with the armed resistance against the Japanese colonial rulers. He was appointed a lieutenant general of an armed Korean resistance group and led several attacks against Japanese forces before his eventual defeat.

Assassination of Itō Hirobumi

In October 1909, Ahn passed the Imperial Japanese guards at the Harbin Railway Station. Itō Hirobumi had come back from negotiating with the Russian representative on the train. Ahn shot Itō three times with an FN M1900 pistol on the railway platform. He also shot Kawagami Toshihiko (川上俊彦), the Japanese Consul General, Morita Jirō (森泰二郞), a Secretary of Imperial Household Agency, and Tanaka Seitarō (田中淸太郞), an executive of South Manchuria Railway, who were seriously injured. After the shooting, Ahn yelled out for Korean independence in Russian, stating "Корея! Ура!", and waving the Korean flag.

Afterwards, Ahn was arrested by Russian guards who held him for two days before turning him over to Japanese colonial authorities. When he heard the news that Itō had died, he made the sign of the cross in gratitude. Ahn was quoted as saying, "I have ventured to commit a serious crime, offering my life for my country. This is the behavior of a noble-minded patriot."[11] Despite the orders from the Bishop of Korea not to administer the Sacraments to Ahn, Fr. Wilhelm disobeyed and went to Ahn to give the Last Sacraments. Ahn insisted that the captors call him by his baptismal name, Thomas.

In the court, Ahn insisted that he be treated as a prisoner of war, as a lieutenant general of the Korean resistance army, instead of a criminal, and listed 15 crimes Itō had committed which convinced him to kill Itō.[12]

"15 reasons why Itō Hirobumi should be killed.

1. Assassinating the Korean Empress Myeongseong

2. Dethroning the Emperor Gojong

3. Forcing 14 unequal treaties on Korea.[13]

4. Massacring innocent Koreans

5. Usurping the authority of the Korean government by force

6. Plundering Korean railroads, mines, forests, and rivers

7. Forcing the use of Japanese banknotes

8. Disbanding the Korean armed forces

9. Obstructing the education of Koreans

10. Banning Koreans from studying abroad

11. Confiscating and burning Korean textbooks

12. Spreading a rumor around the world that Koreans wanted Japanese protection

13. Deceiving the Japanese Emperor by saying that the relationship between Korea and Japan was peaceful when in truth it was full of hostility and conflicts

14. Breaking the peace of Asia

15. Assassinating the Emperor Kōmei.[14]

I, as a lieutenant general of the Korean resistance army, killed the criminal Itō Hirobumi because he disturbed the peace of the Orient and estranged the relationship between Korea and Japan. I hoped that if Korea and Japan be friendlier and are ruled peacefully, they would be a model all throughout the five continents. I did not kill Itō misunderstanding his intentions."

Imprisonment and death

Ahn's Japanese captors showed sympathy to him. He recorded in his autobiography that the public prosecutor, Mizobuchi Takao, exclaimed "From what you have told me, it is clear that you are a righteous man of East Asia. I can't believe a sentence of death will be imposed on a righteous man. There's nothing to worry about." He was also given New Year's delicacies and his calligraphy was highly admired and requested.[11] After six trials, Ahn was sentenced to death by the Japanese colonial court in Ryojun (Port Arthur). Ahn was angered at the sentence, though he expected it.[11] He had hoped to be viewed as a prisoner of war instead of an assassin.[11] On the same day of sentencing at two o'clock in the afternoon, his two brothers Jeong-Geun and Gong-Geun met with him to deliver their mother's message, "Your death is for the sake of your country, and don't ask for your life in a cowardly manner. Your brave death for justice is a final filial regards to your mother." [15]

Judge Hirashi, who presided over Ahn's trial, had promised Ahn that a stay of execution for at least a few months would be granted, but Tokyo ordered prompt action. Before his execution, Ahn made two final requests; that the wardens help him finish his essay, "On Peace in East Asia", and for a set of white silk Korean clothes to die in. The warden granted the second request and resigned shortly afterwards. Ahn requested to be executed as a prisoner of war, by firing squad. But instead it was ordered that he should be hanged as a common criminal. The execution took place in Ryojun, on March 26, 1910. His grave in Lu Shun has not been found.[16]

Views

Some historians hold that Itō's death resulted in the acceleration of the final stage of the colonization process,[11] but the claim has been disputed by some.[17]

According to Donald Keene, author of Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852–1912, Ahn Jung-Geun was an admirer of Emperor Meiji of Imperial Japan.[11] One of the 15 charges Ahn leveled against Itō was that he had deceived the Emperor of Japan, whom Ahn felt desired peace in East Asia and Korean independence. Ahn requested that Meiji be informed of his reasons for his assassination of Itō in the hopes that if Meiji understood his reasons, the emperor would realize how mistaken Itō's policies were and would rejoice. Ahn also felt sure that most Japanese felt similar hatred for Itō, an opinion he formed from talking with Japanese prisoners in Korea.[11] While Ahn was staying in the prison and on the trial, many Japanese prison guards, lawyers and even prosecutors were inspired by Ahn.[18]

Legacy

The assassination of Itō by Ahn was praised by Koreans and many Chinese as well, who were struggling against Japanese invasion at the time. Well-known Chinese political leaders such as Yuan Shikai, Sun Yat-sen, and Liang Qichao wrote poems acclaiming An.[19]

In the 2010 Ahn Jung-Geun Symposium in Korea, Wada Haruki (和田春樹), an activist who once worked at Tokyo University, evaluated Ahn by quoting Itō Yukio (伊藤之雄), a fellow history scholar in Kyoto University.[20] In his text published in 2009, Itō Yukio claims that the reign by Itō Hirobumi resulted in strong resistance from Koreans as it was considered the first step for annexation of Korea due to the cultural differences, and that Ahn is not to be blamed even if he assassinated Itō without understanding Itō's ideology (2009, Itō).

On March 26, 2010, a nationwide centenary tribute to Ahn was held in South Korea, including a ceremony led by the Prime Minister Chung Un-Chan and tribute concerts.

Ancestry

Ahn's family produced many other Korean independence activists. Ahn's cousin An Myeong-Geun (안명근; 安明根) attempted to assassinate Terauchi Masatake, the first Japanese Governor-General of Korea (조선총독; 朝鮮總督) who executed the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty in 1910. He failed, however, and was imprisoned for 15 years; he died in 1926. Ahn's brothers Ahn Jeong-Geun (안정근; 安定根) and Ahn Gong-Geun (안공근; 安恭根), as well as Ahn's cousin Ahn Gyeong-Geun (안경근; 安敬根) and nephew Ahn Woo-Saeng (안우생; 安偶生), joined the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai, China, which led by Kim Gu, and fought against Japan. Ahn Chun-Saeng (안춘생; 安春生), another nephew of Ahn's, joined the National Revolutionary Army of China, participated in battles against Japanese forces at Shanghai, and joined the Korean Liberation Army in 1940. Later, he became a lieutenant general of the Republic of Korea Army and a member of the National Assembly of South Korea.

Pan-Asianism

Ahn strongly believed in the union of the three great countries in East Asia, China, Korea, and Japan in order to counter and fight off the "White Peril", namely, the European countries engaged in colonialism, and restore peace to East Asia. He followed the progress of Japan during the Russo-Japanese War and claimed that he and his compatriots were delighted at hearing of the defeat of one of the agents of the White Peril, but were disappointed that the war ended before Russia was totally subjugated.

Ahn felt that with the death of Itō, Japan and Korea could become friends because of the many traditions that they shared. He hoped that this friendship, along with China, would become a model for the world to follow. His thoughts on Pan-Asianism were stated in his essay, "On Peace in East Asia" (東洋平和論; 동양평화론) that he worked on and left unfinished before his execution.[11][21] In this work, Ahn recommends the organization of combined armed forces and the issue of joint banknotes among Korea, Japan, and China. Sasagawa Norikatsu (笹川紀勝), a Professor of Law at Meiji University, highly praises Ahn's idea as an equivalent of the European Union and a concept that preceded the concept of United Nations by 10 years.[22]

Calligraphic works

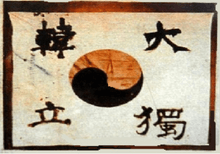

Ahn is highly renowned for calligraphy works. While he was in prison, many prison guards such as Chiba Toshichi (千葉十七) who respected him, made requests to Ahn for calligraphy works.[18] He left many calligraphy works which were written in the jail of Lushun although he hadn't studied calligraphy formally. He would leave on his calligraphy works a signature of "大韓國人" (Great Korean) and a handprint of his left hand that was missing the last joint of the ring finger, which he had cut off with his comrades in 1909 as a pledge to kill Itō. Some of the works were designated as Treasure No. 569 of the Republic of Korea in 1972.[23] One of his famous works is "一日不讀書口中生荊棘" (일일부독서 구중생형극; Unless one reads every day, thorns grow in the mouth), a quote from the Analects of Confucius.

Memorial Halls

Memorial halls for Ahn were erected in Seoul in 1970 by the South Korean government and in Harbin by the Chinese government in 2006.[24] South Korean President Park Geun-Hye raised the idea of erecting a monument for Ahn while meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping during a visit to China in June 2013. Thus another memorial hall honoring Ahn Jung-Geun was opened on Sunday, 19 January 2014 in Harbin. The hall, a 200-square meter room, features photos and memorabilia.[25] Annual activities in memorial of Ahn are held in Lüshun, where he was imprisoned and executed.[26]

According to local sources in China dated on 22 March 2017, the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall located at Harbin Railway Station was recently relocated to a Korean art museum in Harbin City amid China's retaliation over South Korea's deployment of the U.S. THAAD antimissile system.[27]

Controversies

Historically, the Japanese government has generally deemed Ahn Jung-geun as a terrorist and criminal, while South Korea has upheld Ahn as a national hero. In January 2014, Yoshihide Suga, a Japanese government spokesman, described the Harbin memorial hall in China as "not conducive to building peace and stability" between East Asian countries.[28] China, on the other hand, "said that Ahn was a 'famous anti-Japanese high-minded person'", while "South Korea's foreign ministry said Ahn was a 'highly respected figure'."

In February 2017, South Korean police were criticized for using a picture of Ahn in posters put up in the city of Incheon.[29] The poster warned of terrorism, and many South Korean citizens online criticized the police, asking "if it was meant to imply if Ahn was a terrorist". A police officer in the Korea Times apologized and clarified that there was no intention to associate Ahn with terrorism, and all posters were taken down.

In popular culture

The North Korean film An Jung Gun Shoots Itō Hirobumi is a dramatized story of the event.[30] The South Korean film Thomas An Jung-geun (토마스 안중근) is another dramatized story of the event.[31] Released on September 10, 2004, it is directed by Seo Se-won. Ahn Jung-Geun is played by actor Yu Oh-seong and Itō Hirobumi is played by Yoon Joo-sang.

A Chinese-South Korean co-production, "The Age of Heroes," is being planned as a Korean Drama for 2019. “The Age of Heroes” is planned to be 24 episodes long and entirely pre-produced with an impressive budget of 30 billion won. Filming will begin by the end of the year with locations in South Korea, China, and North Korea.[32]

See also

References

- Chung, K. (1910/2004). 대한계년사 9 [History of Korean Empire Vol. 9]. Seoul, South Korea: Somyung. ISBN 89-5626-094-X

- Itō, Y. (2009). 伊藤博文 近代日本を創った男 [Itō Hirobumi – A man who modernized Japan]. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-215909-0.

- Jansen, M. B. (1961). Sakamoto Ryoma and the Meiji Restoration. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0785-5

- Kang, J. (2007). 한국근대사산책 5 [Modern history of Korea Vol.5]. Seoul, South Korea: Inmulgwa Sasang. ISBN 978-89-5906-075-7

- Kim, G. (1928/1997). 백범일지 [Baekbeomilji]. Seoul, Korea: Hakminsa. ISBN 89-7193-086-1

- Nam, K. (1999). 종횡무진 동양사 [History of Eastern Asia] Seoul, South Korea: Greenbee. ISBN 89-7682-051-7

- Ravina, M. (2004). The last samurai: The life and battles of Saigo Takamori. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-08970-2

Notes

- ↑ Ahn was the chief of staff of the Korean Righteous army

- ↑ "What Defines a Hero?". Japan Society. Archived from the original on 2007-10-04. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ↑ "Ito, Hirobumi". Portrait of Modern japanese Historical Figures. Archived from the original on 29 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ↑ "Ito Hirobumi". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ↑ Dudden, Alexis (2005). Japan's Colonization of Korea: Discourse and Power. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2829-1.

- ↑ "Peace of East Asia" Thesis written by An Jung-geun in 1910

- ↑ Shin, Gi-Wook (2006). Ethnic Nationalism in Korea. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-5408-X.

- ↑ Ito, Hirobumi | Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures at www.ndl.go.jp

- ↑ Doosan Encyclopedia

- ↑ Kim, G. (1928/1997, p.48)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Keene, Donald (2002). Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852–1912. Columbia University Press. pp. 662–667. ISBN 0-231-12340-X.

- ↑ Kang.(2007, p.131)

- ↑ For example, see the article Eulsa Treaty

- ↑ Kōmei, who was strongly opposed to radical political changes, died at the age of 35. The official cause of death was smallpox. But there has been a theory widely believed at the time that the emperor was actually poisoned by the anti-Bakufu clique. See for example Chung (1910/2004, p.61), Jansen (1961, p.282), Nam (1999, p.111), and Ravina (2004, p.135).

- ↑ Ahn Jung-Geun, The Great Patriot Martyr of Korea, Patriot Ahn Memorial Hall, November 1995, p. 5

- ↑ 梅泉野録 漢文 ( 3 )

- ↑ 2010 Nocut News article

- 1 2 "Research notes of Ippei Wakabayashi" "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-13. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- ↑ 2009 Joongang Ilbo Article

- ↑ 2010 Kyunghyang News Article

- ↑ 안중근 의사의 <동양평화론> Archived April 18, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 2010 Segye Ilbo article

- ↑ An Jung Geun calligraphy, Treasure No. 569

- ↑ 2009 Asian Business Article

- ↑

- ↑ "韩官方时隔两年到旅顺祭奠安重根" (in Chinese). Yonhap News Agency. 26 March 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "China Relocates Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall". KBS World Radio. March 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Japan protest over Korean assassin Ahn Jung-geun memorial in China". BBC News. 2014-01-20. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- ↑ "South Korean police in terrorism poster gaffe". BBC News. 2017-02-13. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- ↑ DVD in North Korea Books

- ↑ "Thomas Ahn Jung-geun". Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ↑ "Chinese-Korean Joint Drama Announced: "The Age of Heroes" - DramaCurrent". DramaCurrent. 2018-08-21. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to An Jung-geun. |

- An Jung Geun Memorial Hall

- 2009 Lost Memories on IMDb

- "Catholic Church in Korea and the Nationalist Movement". Catholic Bishops' Conference of Korea. Archived from the original on March 22, 2005. Retrieved December 15, 2005.

- Scholarly introduction to An Jung-geun's Treatise on Peace in the East

- An Jung-geun's Treatise on Peace in the East (1910)

- Hero: the Musical, Lincoln Center, New York, 2011