Amphisbaena

The amphisbaena (/ˌæmfɪsˈbiːnə/, plural: amphisbaenae; Ancient Greek: ἀμφίσβαινα) is a mythological, ant-eating serpent with a head at each end. The creature is alternatively called the amphisbaina, amphisbene, amphisboena, amphisbona, amphista, amfivena, amphivena, or anphivena (the last two being feminine), and is also known as the "Mother of Ants". Its name comes from the Greek words amphis, meaning "both ways", and bainein, meaning "to go". According to Greek mythology, the amphisbaena was spawned from the blood that dripped from the Gorgon Medusa's head as Perseus flew over the Libyan Desert with her in his hand, after which Cato's army then encountered it along with other serpents on the march.[1] Amphisbaena fed off of the corpses left behind. The amphisbaena has been referred to by various poets such as Nicander, John Milton, Alexander Pope, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Aimé Césaire, A. E. Housman and Allen Mandelbaum; as a mythological and legendary creature, it has been referenced by Lucan, Pliny the Elder, Isidore of Seville, and Thomas Browne, the last of whom debunked its existence.

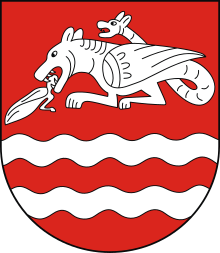

Appearance

The amphisbaena has a twin head, that is one at the tail end as well, as though it were not enough for poison to be poured out of one mouth.

This early description of the amphisbaena depicts a venomous, dual-headed snakelike creature. However, Medieval and later drawings often show it with two or more scaled feet, particularly chicken feet, and feathered wings. Some even depict it as a horned, dragon-like creature with a serpent-headed tail and small, round ears, while others have both "necks" of equal size so that it cannot be determined which is the rear head. Many descriptions of the amphisbaena say its eyes glow like candles or lightning, but the poet Nicander seems to contradict this by describing it as "always dull of eye". He also says: "From either end protrudes a blunt chin; each is far from each other." Nicander's account seems to be referring to what is indeed called the Amphisbaenia.

Habitat

The amphisbaena is said to make its home in the desert.

Folk medicine

In ancient times, the supposedly dangerous amphisbaena had many uses in the art of folk medicine and other such remedies. Pliny notes that expecting women wearing a live amphisbaena around their necks would have safe pregnancies; however, if one's goal was to cure ailments such as arthritis or the common cold, one should wear only its skin.[2] By eating the meat of the amphisbaena, one could supposedly attract many lovers of the opposite sex, and slaying one during the full moon could give power to one who is pure of heart and mind. Lumberjacks suffering from cold weather on the job could nail its carcass or skin to a tree to keep warm, while in the process allowing the tree to be felled more easily.

Origins

In The Book of Beasts, T.H. White suggests that the creature derives from sightings of the worm lizards of the same name.[3] These creatures are found in the Mediterranean countries where many of these legends originated.

In literature

In John Milton's Paradise Lost, after the Fall and the return of Satan to Hell, some of the fallen angelic host are transformed into the amphisbaena, to represent the animal by which the Fall was caused, i.e. a snake. [4] The amphisbaena is mentioned in the first book of Andrzej Sapkowski's The Witcher series, i.e. The Last Wish, when The Witcher's protagonist, Geralt of Rivia, is recalling past events when he meets an old acquaintance named Irion. The amphisbaena was endangering the region of Kovir until the beast was slain by Geralt's hand.

In the 1984 Scandinavian animated film Gallavants, an amphisbaena (called in the film as a 'Vanterviper') appears as a minor antagonist. The two heads, a red one named Edil and a blue one called Fice, frequently disagree and argue, and sing a song about their miserable plight.

See also

References

- ↑ When Cato the Younger’s army marched through Libya

- ↑ Puttock, Sonia (2002). Ritual significance of personal ornament in Roman Britain. Oxford: Archaeopress. p. 93.

- ↑ The Book of Beasts

- ↑ Paradise Lost, 10.524

Bibliography

- Hunt, Jonathan (1998). Bestiary: An Illuminated Alphabet of Medieval Beasts (1st ed.). Hong Kong: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-689-81246-9.

- Levy, Sidney J. (1996). "Stalking the Amphisbaena", Journal of Consumer Research, 23 (3), Dec. 1996, pp. 163–176.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amphisbaena in art. |