American Gothic

| American Gothic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Grant Wood |

| Year | 1930 |

| Type | Oil on beaverboard |

| Dimensions | 78 cm × 65.3 cm (30¾ in × 25¾ in) |

| Location | Art Institute of Chicago |

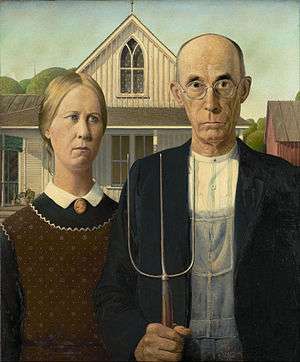

American Gothic is a 1930 painting by Grant Wood in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Wood was inspired to paint what is now known as the American Gothic House in Eldon, Iowa, along with "the kind of people I fancied should live in that house." It depicts a farmer standing beside a woman who has been interpreted to be his daughter or his wife.[1][2]

The figures were modeled by Wood's sister Nan Wood Graham and their dentist Dr. Byron McKeeby. The woman is dressed in a colonial print apron evoking 19th-century Americana, and the man is holding a pitchfork. The plants on the porch of the house are mother-in-law's tongue and beefsteak begonia, which are the same as the plants in Wood's 1929 portrait of his mother Woman with Plants.[3]

American Gothic is one of the most familiar images in 20th-century American art and has been widely parodied in American popular culture.[1][4] In 2016–17, the painting was displayed in Paris at the Musée de l'Orangerie and in London at the Royal Academy of Arts in its first showings outside the United States.[5][6][7]

Creation

In August 1930, Grant Wood, an American painter with European training, was driven around Eldon, Iowa, by a young painter from Eldon, John Sharp. Looking for inspiration, Wood noticed the Dibble House, a small white house built in the Carpenter Gothic architectural style.[8] Sharp's brother suggested in 1973 that it was on this drive that Wood first sketched the house on the back of an envelope. Wood's earliest biographer, Darrell Garwood, noted that Wood "thought it a form of borrowed pretentiousness, a structural absurdity, to put a Gothic-style window in such a flimsy frame house."[9] At the time, Wood classified it as one of the "cardboardy frame houses on Iowa farms" and considered it "very paintable".[10] After obtaining permission from the Jones family, the house's owners, Wood made a sketch the next day in oil on paperboard from the house's front yard. This sketch displayed a steeper roof and a longer window with a more pronounced ogive than on the actual house, features which eventually adorned the final work.

Wood decided to paint the house along with "the kind of people I fancied should live in that house."[1] He recruited his sister Nan (1899–1990) to model the woman, dressing her in a colonial print apron mimicking 19th-century Americana. The man is modeled on Wood's dentist,[11] Dr. Byron McKeeby (1867–1950) from Cedar Rapids, Iowa.[12][13] Nan, perhaps embarrassed about being depicted as the wife of a man twice her age, told people that her brother had envisioned the couple as father and daughter, rather than husband and wife, which Wood himself confirmed ("The prim lady with him is his grown-up daughter") in his letter to a Mrs. Nellie Sudduth in 1941.[1][14]

Elements of the painting stress the vertical that is associated with Gothic architecture. The three-pronged pitchfork is echoed in the stitching of the man's overalls, the Gothic window of the house, and the structure of the man's face.[15] However, Wood did not add figures to his sketch until he returned to his studio in Cedar Rapids.[16] He would not return to Eldon again before his death in 1942, although he did request a photograph of the home to complete his painting.[8]

Reception

Wood entered the painting in a competition at the Art Institute of Chicago. One judge deemed it a "comic valentine", but a museum patron persuaded the jury to award the painting the bronze medal and $300 cash prize.[17] The patron also persuaded the Art Institute to buy the painting, and it remains part of the museum's collection.[2] The image soon began to be reproduced in newspapers, first by the Chicago Evening Post and then in New York, Boston, Kansas City, and Indianapolis. However, Wood received a backlash when the image finally appeared in the Cedar Rapids Gazette. Iowans were furious at their depiction as "pinched, grim-faced, puritanical Bible-thumpers."[18] Wood protested that he had not painted a caricature of Iowans but a depiction of his appreciation, stating "I had to go to France to appreciate Iowa."[11]

Art critics who had favorable opinions about the painting, such as Gertrude Stein and Christopher Morley, also assumed the painting was meant to be a satire of rural small-town life. It was thus seen as part of the trend toward increasingly critical depictions of rural America, along the lines of Sherwood Anderson's 1919 Winesburg, Ohio, Sinclair Lewis's 1920 Main Street, and Carl Van Vechten's 1924 The Tattooed Countess in literature.[1]

Yet another interpretation sees it as an "old-fashioned mourning portrait... Tellingly, the curtains hanging in the windows of the house, both upstairs and down, are pulled closed in the middle of the day, a mourning custom in Victorian America. The woman wears a black dress beneath her apron, and glances away as if holding back tears. One imagines she is grieving for the man beside her..." Wood had been only 10 when his father had died and later had lived for a decade "above a garage reserved for hearses," so death was on his mind.[19]

However, with the onset of the Great Depression, the painting came to be seen as a depiction of steadfast American pioneer spirit. Wood assisted this transition by renouncing his Bohemian youth in Paris and grouping himself with populist Midwestern painters, such as John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton, who revolted against the dominance of East Coast art circles. Wood was quoted in this period as stating, "All the good ideas I've ever had came to me while I was milking a cow."[1]

Parodies

The Depression-era understanding of the painting as a depiction of an authentically American scene prompted the first well-known parody, a 1942 photo by Gordon Parks of cleaning woman Ella Watson, shot in Washington, D.C.[1]

American Gothic is a frequently parodied image. It has been lampooned in Broadway shows such as The Music Man, movies such as The Rocky Horror Picture Show, television shows such as Green Acres and the Dick Van Dyke Show episode "The Masterpiece", marketing campaigns, pornography, and by couples who recreate the image by facing a camera, one of them holding a pitchfork or other object in its place.[1][4]

American Gothic, Washington, D.C. (1942) by Gordon Parks was the first prominent parody of the painting.

American Gothic, Washington, D.C. (1942) by Gordon Parks was the first prominent parody of the painting. Visitors dressing up and taking their photograph outside the American Gothic House in Eldon, Iowa.

Visitors dressing up and taking their photograph outside the American Gothic House in Eldon, Iowa.

In popular culture

"Anarchic Emoting" (an anagram of 'American Gothic') by Northern Irish poet Colin Dardis, in his collection the x of y (Eyewear Publishing, 2018), is written in the voice of the woman from the painting.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fineman, Mia (June 8, 2005). "The Most Famous Farm Couple in the World: Why American Gothic still fascinates.". Slate.

- 1 2 "About This Artwork: American Gothic". The Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ↑ "The Painting". American Gothic House. Retrieved 2015-01-08.

- 1 2 Güner, Fisun (8 February 2017). "How American Gothic became an icon". BBC. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ↑ Cumming, Laura (5 February 2017). "American Gothic: a state visit to Britain for the first couple". Retrieved 2 March 2017 – via The Guardian.

- ↑ "American Painting in the 1930's - Musée de l'Orangerie". musee-orangerie.fr. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ↑ Artwork 6565 Art Institute of Chicago

- 1 2 "American Gothic House Center". Wapello County Conservation Board. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- ↑ Garwood, p. 119

- ↑ Qtd. in Hoving, p. 36

- 1 2 Semuels, Alana (April 30, 2012). "At Home in a Piece of History". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ↑ Byron McKeeby's contribution to Grant Wood's "American Gothic"

- ↑ The models for American Gothic

- ↑ "Grant Wood's Letter Describing American Gothic". Campsilos.org. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ↑ "Grant Wood's American Gothic". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ↑ Qtd. in Biel, p. 22

- ↑ Biel, Steven (2005). American Gothic: A Life of America's Most Famous Painting. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 28. ISBN 0-393-05912-X.

- ↑ Andréa Fernandes. "mental_floss Blog » Iconic America: Grant Wood". Mentalfloss.com. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ↑ Deborah Solomon (October 28, 2010). "Gothic American". The New York Times.

Works

- Garwood, Darrell (1944). Artist in Iowa: A Life of Grant Wood. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. OCLC 518305.

- Hoving, Thomas (2005). American Gothic: The Biography of Grant Wood's American Masterpiece. New York: Chamberlain Bros. ISBN 1-59609-148-7.

- Girod, André (2014). American Gothic: une mosaïque de personnalités américaines (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-343-04037-0.

Further reading

- Howard, Beth M. (2018-03-18). "Masterpiece Rental: My Life in the 'American Gothic' House". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-05. (contains image of first Wood sketch of the house)

External links

| |

|

| |

|

|

- Grant Wood and Frank Lloyd Wright Compared

- About the painting, on the Art Institute's site

- Slate article about American Gothic

- American Gothic, French

- American Gothic: A Life of America's Most Famous Painting

- Television Commercials (1950s-1960s) contains General Mills New Country Corn Flakes commercial

- American Gothic sculpture removed from Michigan Avenue

- American Gothic Parodies collection

- November 18, 2002, National Public Radio Morning Edition report about American Gothic by Melissa Gray that includes an interview with Art Institute of Chicago curator Daniel Schulman.

- June 6, 1991, National Public Radio Morning Edition report on Iowa's celebration of the centennial of Grant Wood's birth by Robin Feinsmith. Several portions of the report focus on American Gothic.

- February 13, 1976, National Public Radio All Things Considered Cary Frumpkin interview with James Dennis, author of Grant Wood: A Study in American Art and Culture. The interview contains a discussion about American Gothic.