Amblypygi

| Amblypygi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Heterophrynus, Ecuador | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Amblypygi Thorell, 1883 |

| Families | |

| |

Amblypygi is an ancient order of arachnid chelicerate arthropods also known as whip spiders and tailless whip scorpions (not to be confused with whip scorpions and vinegaroons that belong to the related order Thelyphonida). The name "amblypygid" means "blunt rump", a reference to a lack of the flagellum ("tail") that is otherwise seen in whip scorpions. They are harmless to humans.[2][3] Amblypygids possess no silk glands or venomous fangs. They rarely bite if threatened, but can grab fingers with their pedipalps, resulting in thorn-like puncture injuries.

As of 2016, 5 families, 17 genera and around 155 species had been discovered and described.[4] They are found in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide; they are mainly found in warm and humid environments and like to stay protected and hidden within leaf litter, caves, or underneath bark. Some species are subterranean; all are nocturnal. Fossilized amblypygids have been found dating back to the Carboniferous period, such as Graeophonus.

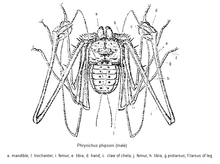

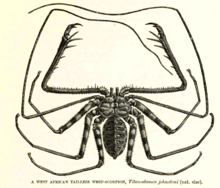

Physical description

Amblypygids range from 5 to 70 centimetres (2.0 to 27.6 in) in legspan.[4][6] Their bodies are broad and highly flattened, with a solid carapace and a segmented abdomen. Most species have eight eyes; a pair of median eyes at the front of the carapace above the chelicerae and 2 smaller clusters of three eyes each further back on each side.

Amblypygids have raptorial pedipalps modified for grabbing and retaining prey, much like those of a mantis.[7] The first pair of legs act as sensory organs and are not used for walking. The sensory legs are very thin and elongate, have numerous sensory receptors, and can extend several times the length of body.[4]

Behaviour

Amblypygids have eight legs, but use only six for walking, often in a crab-like, sideways fashion. The front pair of legs are modified for use as antennae-like feelers, with many fine segments giving the appearance of a "whip". When a suitable prey is located with the antenniform legs, the amblypygid seizes its victim with large spines on the grasping pedipalps, impaling and immobilizing the prey.[8] Pincer-like chelicerae then work to grind and chew the prey prior to ingestion.

Courtship involves the male depositing stalked spermatophores, which have one or more sperm masses at the tip, onto the ground, and using his pedipalps to guide the female over them.[9] She gathers the sperm and lays fertilized eggs into a sac carried under the abdomen. When the young hatch, they climb up onto the mother's back; any which fall off before their first moult will not survive.

Some species of amblypygids, particularly Phrynus marginemaculatus and Damon diadema, may be among the few examples of arachnids that exhibit social behavior. Research conducted at Cornell University suggests that mother amblypygids communicate with their young with her antenniform front legs, and the offspring reciprocate both with their mother and siblings. The ultimate function of this social behavior remains unknown.[10] Amblypygids hold territories that they defend from other individuals.[11]

The amblypygid diet mostly consists of arthropod prey, but this opportunistic predator has also been observed feeding on vertebrates.[4] Amblypygids generally do not feed before, during, and after moulting. Like other arachnids, an amblypygid will moult several times during its life.[4]

Genera

The following genera are recognised:[12][13]

- Palaeoamblypygi Weygoldt, 1996

- Paracharontidae Weygoldt, 1996

- †Graeophonus Scudder, 1890 (2-3 species, Carboniferous)[14]

- Paracharon Hansen, 1921 (1 species)

- †Paracharonopsis Engel & Grimaldi, 2014 (1 species, Eocene)

- Euamblypygi Weygoldt, 1996

- Charinidae Weygoldt, 1996

- Catageus Thorell, 1889 (1 species)

- Charinus Simon, 1892 (33 species)

- Sarax Simon, 1892 (10 species)

- Neoamblypygi Weygoldt, 1996

- Charontidae Simon, 1892

- Charon Karsch, 1879 (5 species)

- Stygophrynus Kraepelin, 1895 (7 species)

- Unidistitarsata Engel & Grimaldi, 2014

family unspecified

- †Kronocharon Engel & Grimaldi, 2014 (1 species, Cretaceous)

- Phrynoidea Blanchard, 1852

- Phrynichidae Simon, 1900

- Damon C. L. Koch, 1850 (10 species)

- Euphrynichus Weygoldt, 1995 (2 species)

- Musicodamon Fage, 1939 (1 species)

- Phrynichodamon Weygoldt, 1996 (1 species)

- Phrynichus Karsch, 1879 (16 species)

- Trichodamon Mello-Leitão, 1935 (2 species)

- Xerophrynus Weygoldt, 1996 (1 species)

- Phrynidae Blanchard, 1852

- Acanthophrynus Kraepelin, 1899 (1 species)

- †Britopygus Dunlop & Martill, 2002 (1 species; Cretaceous)

- †Electrophrynus Petrunkevich, 1971 (1 species; Miocene)

- Heterophrynus Pocock, 1894 (14 species)

- Paraphrynus Moreno, 1940 (18 species)

- Phrynus Lamarck, 1801 (28 species, Oligocene - Recent)

- † Sorellophrynus Harvey, 2002 (1 species, Upper Carboniferous)

- † Thelyphrynus Petrunkevich, 1913 (1 species, Upper Carboniferous)

References

- ↑ Garwood, Russell J.; Dunlop, Jason A.; Knecht, Brian J.; Hegna, Thomas A. (2017). "The phylogeny of fossil whip spiders". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17: 105. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-0931-1. PMC 5399839. PMID 28431496.

- ↑ "Pedipalpi". The international wildlife encyclopedia. 1 (3 ed.). Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish. 2002. p. 1906. ISBN 0-7614-7267-3. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- ↑ Takashima, Haruo (1950). "Notes on Amblypygi Found in Territories Adjacent to Japan". Pacific Science. 4 (4): 336–338. hdl:10125/9019. ISSN 0030-8870.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chapin, KJ; Hebets, EA (2016). "Behavioral ecology of amblypygids". Journal of Arachnology. 44 (1): 1–14.

- ↑ R. I. Pocok (1900). Fauna of British India. Arachnida.

- ↑ https://www.amazon.com/Whip-Spiders-Morphology-Systematics-Chelicerata/dp/8788757463

- ↑ Robert D. Barnes (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 617–619. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ↑ Ladle, Richard J.; Velander, Kathryn (2003). "Fishing behavior in a giant whip spider" (PDF). The Journal of Arachnology. 31: 154–156 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ Peter Weygoldt (1999). "Spermatophores and the evolution of female genitalia in whip spiders (Chelicerata, Amblypygi)" (PDF). Journal of Arachnology. 27 (1): 103–116. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Rayor, Linda (December 2017). "Social Behavior in Amblypygids, and a Reassessment of Arachnid Social Patterns". Journal of Arachnology. 31 (12): 399–421. doi:10.1636/S04-23.1. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ↑ Chapin KJ; Hill-Lindsay S (2015). "Territoriality evidenced by asymmetric intruder-holder motivation in an amblypygid". Behavioural Processes. 122: 110–115.

- ↑ Mark S. Harvey (2003). "Order Amblypygi". Catalogue of the smaller arachnid orders of the world: Amblypygi, Uropygi, Schizomida, Palpigradi, Ricinulei and Solifugae. CSIRO Publishing. pp. 3–58. ISBN 978-0-643-06805-6.

- ↑ Engel, M.S.; Grimaldi, D.A. (2014). "Whipspiders (Arachnida: Amblypygi) in amber from the Early Eocene and mid-Cretaceous, including maternal care". Novitates Paleoentomologicae. 9: 1–17.

- ↑ Dunlop, J.A.; Zhou, G.R.S.; Braddy, S.J. (2007). "The affinities of the Carboniferous whip spider Graeophonus anglicus Pocock, 1911 (Arachnida:Amblypygi)". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 98: 165–178. doi:10.1017/S1755691007006159.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amblypygi. |

- Amblypigid video summarizing research from University of Nebraska's Eben Gering

- Amblypygi. The Antillean (West Indian) fauna.