Alpine Fault

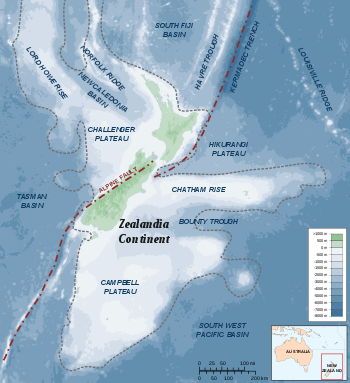

The Alpine Fault is a geological fault, specifically a right-lateral strike-slip fault, that runs almost the entire length of New Zealand's South Island. It forms a transform boundary between the Pacific Plate and the Indo-Australian Plate. Earthquakes along the fault, and the associated earth movements, have formed the Southern Alps. The uplift to the southeast of the fault is due to an element of convergence between the plates, meaning that the fault has a significant high-angle reverse oblique component to its displacement.

The Alpine Fault is believed to align with the Macquarie Fault Zone in the Puysegur Trench off the southwestern corner of the South Island. From there, the Alpine Fault runs along the western edge of the Southern Alps, before splitting into a set of smaller dextral strike-slip faults north of Arthur's Pass, known as the Marlborough Fault System. This set of faults, which includes the Wairau Fault, the Hope Fault, the Awatere Fault, and the Clarence Fault, transfer displacement between the Alpine Fault and the Hikurangi subduction zone to the north.[1] The Hope fault is thought to represent the primary continuation of the Alpine fault.[1]

Average slip rates in the fault's central region are about 30mm a year, very fast by global standards.[2]

Major ruptures

Over the last thousand years, there have been four major ruptures along the Alpine Fault causing earthquakes of about magnitude 8. These had previously been determined to have occurred in approximately 1100, 1430, 1620 and 1717 CE, at intervals between 100 and 350 years.[2] The 1717 quake appears to have involved a rupture along nearly 400 kilometres (250 mi) of the southern two-thirds of the fault. Scientists say that a similar earthquake could happen at any time as the interval since 1717 is longer than between the earlier events.[3] Newer research carried out by the University of Otago and the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation revised the dates of the pre-1717 earthquakes to between 1535 and 1596 (instead of 1620), 1374 and 1405 (instead of 1430), and 1064 and 1120 (instead of 1100). In addition, an earlier earthquake was identified to have occurred between 887 and 965.[4]

In 2012, GNS Science researchers published an 8000-year timeline of 24 major earthquakes on the (southern end of the) fault from sediments at Hokuri Creek, near Lake McKerrow in north Fiordland. In earthquake terms, the 850 kilometres (530 mi) long fault is remarkably consistent, rupturing on average every 330 years, at intervals ranging from 140 years to 510 years.[5] In 2017, GNS researchers revised the figures after they combined updated Hokuri site records with a thousand year record from another site 20km away at John O'Groats River to produce a record of 27 major earthquake events during the 8000-year period. This gave a mean recurrence rate of 291 years, plus or minus 23 years, down from the previously estimated rate of 329 years, plus or minus 26 years. In the new study, the interval between earthquakes ranged from 160 to 350 years and the probability of an earthquake occurring in the following 50 years was estimated at 29 per cent.[6]

Large ruptures can also trigger earthquakes on the faults continuing north from the Alpine Fault. There is paleotsunami evidence of near-simultaneous ruptures of the Alpine fault and Wellington (and/or other major) faults to the North having occurred at least twice in the past 1,000 years.[7]

Effects of Alpine Fault rupture

A 2018 study says that a significant rupture in the Alpine Fault could lead to roads (particularly in or to the West Coast) being blocked for months, as with the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake, with problems in supplying towns and evacuating tourists. [8] [9]

Earthquakes in historic times

The Alpine Fault and its northern offshoots have experienced sizable earthquakes in historic times:

- 1848 – Marlborough, estimated magnitude = 7.5

- 1888 – North Canterbury, estimated magnitude = 7.3

- 1929 – Arthur's Pass, estimated magnitude = 7.1

- 1929 – Murchison, estimated magnitude = 7.8

- 1968 – Inangahua, estimated magnitude = 7.1

- 2003 – Fiordland, estimated magnitude = 7.1

- 2009 – Fiordland, estimated magnitude = 7.8

Hydrothermal activity

In 2017 scientists reported they had discovered beneath Whataroa, a small township on the Alpine Fault, "extreme" hydrothermal activity which "could be commercially very significant".[10][11]

See also

References

- 1 2 Zachariasen, J.; Berryman, K.; Langridge, R.; Prentice, C.; Rymer, M.; Stirling, M.; Villamor, P. (2006). "Timing of late Holocene surface rupture of the Wairau Fault, Marlborough, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 49: 159–174. doi:10.1080/00288306.2006.9515156. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Alpine Fault". GNS Science. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ Booker, Jarrod (24 August 2006). "Deadly alpine quake predicted". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ Gorman, Paul (1 November 2012). "Great quakes' debris tracked". The Press. p. A5. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ "'Well Behaved' Alpine Fault – experts respond". Science Media Centre. 28 June 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ "New study says Alpine Fault quake interval shorter than thought: GNS Science". stuff www.stuff.co.nz. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ↑ Goff, J.R.; Chague-Goff, C. (2001). "Catastrophic events in New Zealand coastal environments" (PDF). Conservation Advisory Science Notes No. 333. Department of Conservation / GeoEnvironmental Consultants. ISSN 1171-9834. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ "Videos show devastating impact across South Island if Alpine Fault ruptures". Stuff (Fairfax). 16 May 2018.

- ↑ "Thousands to be evacuated, highways blocked for months when Alpine Fault ruptures". Stuff (Fairfax). 26 May 2018.

- ↑ Sutherland, R.; Townend, J.; Toy, V.; Upton, P. and 62 others (1 June 2017). "Extreme hydrothermal conditions at an active plate-bounding fault". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature22355. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ "Geothermal discovery on West Coast". Otago Daily Times. 18 May 2017.

Sources

- Robinson, R. (2003). Potential earthquake triggering in a complex fault network: the northern South Island, New Zealand. Geophysical Journal International, 159(2), 734–748.

- Wells, A.; Yetton, M.T.; Duncan, R.P.; and Stewart, G.H. (1999). Prehistoric dates of the most recent Alpine fault earthquakes, New Zealand. Geology, 27(11), 995–998. (abstract)

External links

- Alpine Fault earthquake talk – Otago Regional Council

- Alpine Fault research in the Department of Geology – University of Otago

- Where were New Zealand’s largest earthquakes? – GNS Science

- Earthquakes and Tectonics in New Zealand – Nature & Company Limited

- The Next Alpine Fault Earthquake in New Zealand – GNS Science on YouTube