Aimé Bonpland

| Aimé Bonpland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

August 1773 La Rochelle, France |

| Died |

May 1858 (aged 84) Paso de los Libres, Argentina |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Known for | Travel with Alexander von Humboldt |

| Awards | French Academy of Sciences |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physician, biologist, botanist, natural history |

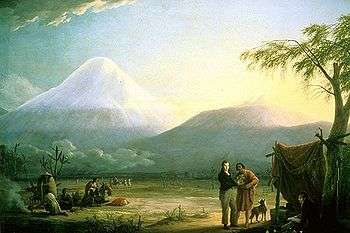

Aimé Jacques Alexandre Bonpland[1] (August 1773 – May 1858) was a French explorer and botanist who traveled with Alexander von Humboldt in Latin America from 1799 to 1804. He co-authored volumes of the scientific results of their expedition.

The standard author abbreviation Bonpl. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[2]

Biography

Bonpland was born as Aimé Jacques Alexandre Goujaud[3] in La Rochelle, France, on 22,[4][1][3] 28,[5][6] or 29 August 1773. His father was a physician[7] and, around 1790, he joined his brother Michael in Paris, where they both studied medicine.[8] From 1791, they attended courses given at Paris's Botanical Museum of Natural History. Their teachers included Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Antoine Laurent de Jussieu, and René Louiche Desfontaines;[8] Aimé further studied under Jean-Nicolas Corvisart[4] and may have attended classes given by Pierre-Joseph Desault at the Hôtel-Dieu. During this period, Aimé also befriended his fellow student, Marie François Xavier Bichat.

Amid the turmoil of the French Revolution and Revolutionary Wars, Bonpland served as a surgeon in the French army[1] or navy.[4][7][9][3]

Having befriended Alexander von Humboldt at Corvisart's house,[7] he joined him on a five-year journey through Mexico, Colombia, and the Orinoco and Amazon basins.[4] During this trip, he collected and classified about 6,000 plants that were mostly unknown in Europe up to that time.[4] His account of these findings was published as a series of volumes from 1808 to 1816 entitled Equatorial Plants (French: Plantes equinoxiales).[4]

Upon his return to Paris, Napoleon granted him a pension of 3000 francs per year in return for the many specimens he bestowed upon the Museum of Natural History.[7] The Empress Josephine was very fond of him and installed him as superintendent over the gardens at Malmaison,[4][7] where many seeds he had brought from the Americas were cultivated.[7] In 1813, he published his Description of the Rare Plants Cultivated at Malmaison and in Navarre (Description des plantes rares cultivées à Malmaison et à Navarre).[4] During this period, he also became acquainted with Gay-Lussac, Arago, and other eminent scientists and, after the abdication of Fontainebleau, vainly pleaded with Napoleon to retire to Mexico.[4][7] He was present at Josephine's deathbed.[7]

In 1816, he took various European plants to Buenos Aires, where he was elected professor of natural history.[4] He soon left his post, however, to explore the interior of South America.[4] In 1821, he established a colony at Santa Ana near the Paraná for the specific object of harvesting and selling yerba mate.[10] The colony was located in territory claimed by both Paraguay and Argentina; further, the Paraguayan government of dictator José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia had a monopoly in the commercial trade of yerba mate. The Paraguayans therefore destroyed the colony and Bonpland was arrested as a spy and detained at Santa Maria, Paraguay [11] until 1829.[4][12] During his captivity, he married and had several children.[13] He was given freedom of movement and acted as a physician for the local poor[4] and the military garrison.[9] At the same epoch, the Swiss naturalist Johann Rudolph Rengger also stayed in Paraguay: he was not allowed to cross the strictly guarded border, but was free to circulate pending the request of a special permit for each excursion.[14]

Bonpland was freed in 1829[7] and in 1831[4] returned to Argentina, where he settled at San Borja in Corrientes.[4] There, aged 58, he married a local woman and made a living farming and trading in yerba mate.[9][15] In 1853, he returned to Santa Ana, where he cultivated the orange trees he had introduced.[4] He received a 10 000-piastre estate from the Corrientes government in gratitude for his work in the province.[4] The small town around it is now known as "Bonpland" in his honor. A different small town in Misiones province just south of Santa Ana (Misiones) is also named Bonpland.

He died at age 84, at San Borja,[7] Santa Ana,[3] or Restauración[5] on 4[1] or 11[5] May 1858, before his planned return to Paris.[4]

Legacy

Bonpland's biography was written by Adolphe Brunel.[16] A fictionalized account of his travels with Humboldt occurs in Daniel Kehlmann's Die Vermessung der Welt, translated by Carol Brown Janeway as Measuring the World: A Novel.

Bonpland Street in the ritzy Buenos Aires neighborhood of Palermo Hollywood lies among streets named after Charles Darwin, Robert FitzRoy, and Alexander von Humboldt. There is also a Bonpland Street in the city of Bahía Blanca, Argentins, in Caracas, Venezuela, and in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Many animals and plants are also named in his honor, including the squid Grimalditeuthis bonplandi and the orchid Ornithocephalus bonplandi.

The lunar crater Bonpland is named after him. Also Pico Bonpland in the Venezuelan Andes is named to his honor, although he never visited the Venezuelan Andes. A peak of over 2,300 m (7,500 ft) in New Zealand also bears his name. The mountain is near the head of Lake Wakatipu in the South Island.

Taxonomic descriptions

The following genera and species have been named or described by Aimé Bonpland.

Genera

Species

- Acacia subulata

- Alchornea castaneifolia

- Arceuthobium vaginatum

- Aristida divaricata

- Arrabidaea chica

- Astragalus geminiflorus

- Banksia marginata

- Brachyotum confertum

- Bertholletia excelsa

- Brugmansia suaveolens

- Brunellia ovalifolia

- Cavanillesia platanifolia

- Centronia mutisii

- Cephalanthus salicifolius

- Ceroxylon alpinum

- Chuquiraga jussieui

- Claytonia perfoliata

- Coriaria thymifolia

- Dorstenia tenuis

- Draba violacea

- Eucalyptus diversifolia

- Eudema nubigena

- Eugenia albida

- Huperzia crassa

- Hydrocleys nymphoides

- Iochroma fuchsioides

- Ipomoea arborescens

- Iresine diffusa

- Jacksonia furcellata

- Juniperus phoenicea

- Lilaea scilloides

- Limnobium laevigatum

- Limnocharis flava

- Ludwigia helminthorrhiza

- Ludwigia sedioides

- Maurandya antirrhiniflora

- Melaleuca pallida

- Miconia caelata

- Miconia guayaquilensis

- Miconia lacera

- Miconia minutiflora

- Miconia theaezans

- Mimosa somnians

- Monochaetum multiflorum

- Passiflora arborea

- Pinguicula moranensis

- Prosopis laevigata

- Prosopis pallida

- Prumnopitys montana

- Quararibea cordata

- Quercus crassifolia

- Quercus crassipes

- Quercus depressa

- Quercus diversifolia

- Quercus humboldtii

- Quercus mexicana

- Quercus obtusata

- Quercus xalapensis

- Smilax havanensis

- Stanhopea grandiflora

- Stanhopea jenischiana

- Styrax tomentosus

- Symphoricarpos microphyllus

- Symplocos coccinea

- Tagetes zypaquirensis

- Theobroma bicolor

- Trichilia acuminata

- Viola cheiranthifolia

- Vitis tiliifolia

- Zieria laevigata

Works

- 1805: Essai sur la géographie des plantes. Written with Alexander von Humboldt.

- 1811: A collection of observations on zoology and comparative anatomy written with Alexander von Humboldt, Printing JH Stone, Paris. Digital version at the website Gallica.

- 1813: Description of rare plants grown at Malmaison and Navarre by Aimé Bonpland. Printing P. The elder Didot, Paris. By Aimé Bonpland dedicated to the Empress Joséphine. Digital version at the website Botanicus, and Digital version of the illustrations at the website of the Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de santé (Interuniversity Library of Health).

- 1815: Nova plantarum genera and species written with Alexander von Humboldt and Karl Sigismund Kunth, Volume 1, Lutetiae Parisiorum, Paris. Digital version at the website Botanicus.

- 1816: Monograph Melastomacées including all plants of this order including Rhexies, Volume 1, Paris.

- 1817: Nova plantarum genera and species written with Alexander von Humboldt and Karl Sigismund Kunth, Volume 2, Lutetiae Parisiorum, Paris. Digital version at the website Botanicus.

- 1818: Nova plantarum genera and species written with Alexander von Humboldt and Karl Sigismund Kunth, Volume 3, Lutetiae Parisiorum, Paris. Digital version at the website Botanicus.

- 1820: Nova plantarum genera and species written with Alexander von Humboldt and Karl Sigismund Kunth, Volume 4, Lutetiae Parisiorum, Paris. Digital version at the website Botanicus.

- 1821: Nova plantarum genera and species written with Alexander von Humboldt and Karl Sigismund Kunth, Volume 5, Lutetiae Parisiorum, Paris. Digital version at the website Botanicus.

- 1823: Nova plantarum genera and species written with Alexander von Humboldt and Karl Sigismund Kunth, Volume 6, Lutetiae Parisiorum, Paris. Digital version at the website Botanicus.

- 1823: Monograph Melastomacées including all plants of this order including Rhexies, Volume 2, Paris.

- 1825: Nova plantarum genera and species written with Alexander von Humboldt and Karl Sigismund Kunth, Volume 7, Lutetiae Parisiorum, Paris. Digital version at the website Botanicus.

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm (1911).

- ↑ IPNI. Bonpl.

- 1 2 3 4 ACAB (1900).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 EB (1878).

- 1 2 3 Smith, Charles (2007), "Aimé Jacques Alexandre (Goujaud) Bonpland", Some Biogeographers, Evolutionists, and Ecologists: Chrono-Biographical Sketches .

- ↑ Parish register. Paroisse Saint-Barthélémy, La Rochelle. Archives départementales, Charente-Maritime, Archives en ligne.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 AJSA (1858).

- 1 2 Stephen Bell (2010). A Life in Shadow: Aimé Bonpland in Southern South America, 1817–1858 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780804774277.

- 1 2 3 AC (1879).

- ↑ Stephen Bell (2010). A Life in Shadow: Aimé Bonpland in Southern South America, 1817–1858 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 196. ISBN 9780804774277.

- ↑ Rengger, Johan Rudolf: (1827) Ensayo Historico

- ↑ Chavez, Julios Cesar (1942), El Supremo Dictador . (in Spanish)

- ↑ Schinini, Aurelio (2013) Aimé Bonpland: Un naturalista francés en Corrientes.

- ↑ Albert Schumann (1889), "Rengger, Johann Rudolf", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), 28, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 220–222

- ↑ Obregón (1999), "Los soportes histórico y científico de la pieza Humboldt & Bonpland, taxidermistas de Ibsen Martínez", Latin American Theatre Review . (in Spanish)

- ↑ Paris, 1872.

Bibliography

- "Misc. Scientific Intelligence: Death of Bonpland", The American Journal of Science and Arts, 2nd Series, Vol. XXVI, No. LXXVII, New Haven: Hayes, November 1858, pp. 301 ff .

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Aimé Bonpland |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aimé Bonpland. |

- Works by Aimé Bonpland at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Aimé Bonpland at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Aimé Bonpland at Internet Archive

- View biographical information in Australian National Botanic Gardens

- View biographical information on and digitized titles by Aimė Bonpland in Botanicus.org