African bush elephant

| African bush elephant[1] | |

|---|---|

_male_(17289351322).jpg) | |

| A male African bush elephant, Loxodonta africana, in Kruger National Park, South Africa | |

_female_with_six-week-old_baby.jpg) | |

| female with six-week-old calf, Zimbabwe | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | Loxodonta |

| Species: | L. africana |

| Binomial name | |

| Loxodonta africana (Blumenbach, 1797) | |

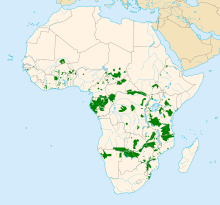

| |

| Distribution of Loxodonta (2007) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), also known as the African savanna elephant, is the larger of the two species of African elephants, and the largest living terrestrial animal. These elephants were previously regarded as the same species, but the African forest elephant has been reclassified as L. cyclotis.

The bush elephant is much larger in height and weight than the forest elephant, while the forest elephant has rounder ears and a trunk that tends to be more hairy. The adult bush elephant has no predators other than humans. While the most numerous of the three extant elephant species, its population continues to decline due to poaching for ivory and destruction of habitat. Elephants are social animals, traveling in herds of females and adolescents, while adult males usually live alone. The desert elephant or desert-adapted elephant is not a distinct species of elephant, but are African bush elephants that live in the Namib and Sahara deserts.

Taxonomy

The African bush elephant and the African forest elephant were once considered to be a single species, but recent genetic studies have revealed that they are separate species and split 2 to 7 million years ago.

Differences between species

A detailed genetic study in 2010 confirmed that the African bush elephant and the African forest elephant are distinct species.[3][4] By sequencing DNA of 375 nuclear genes, scientists determined that the two species diverged around the same time as the Asian elephant and the woolly mammoth, and are as distinct from one another as those two species are from each other.[5] As of December 2010, conservation organizations, such as the United Nations Environment Programme's World Conservation Monitoring Centre and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), had not distinguished between the two species of African elephants for purposes of assessing their conservation status. As of March 2010, the IUCN Red List classified African elephants as a whole as vulnerable species and the Central African elephant population (forest elephants) as endangered.[2][4]

Another possible species or subspecies formerly existed; although formally described[6][7] it has not been widely recognized by the scientific community. The North African elephant (L. a. pharaohensis), also known as the Carthaginian elephant or Atlas elephant, was the animal famously used as a war elephant by Carthage in its many wars with Rome.

Characteristics and anatomy

The African bush elephant has several distinct features which sets them apart from other similar species. They are generally larger than the African forest elephant, which has rounder ears and straighter tusks. The bush elephant is known to have a concave back with stocky legs and a thickset body, compared to the Asian elephant who has a convex back.[8] The African bush elephant’s trunk has more than 40,000 muscles and tendons that allows them to lift heavy objects. They also tend to have dull brownish-grey skin that is wrinkly with black bristly hairs, large ears, and a long and flattened tail. The skull of the African elephant is very large, making up twenty-five percent of its total body weight.[9] The estimated population size is near 300,000, and they usually live up to 70 years in age when in the wild. However, in captivity, they tend to only live up 65 years.[10]

Female African bush elephant skeleton on display at the Museum of Osteology, Oklahoma City

Female African bush elephant skeleton on display at the Museum of Osteology, Oklahoma City Male African bush elephant skull on display at the Museum of Osteology, Oklahoma City

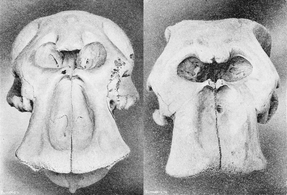

Male African bush elephant skull on display at the Museum of Osteology, Oklahoma City Skulls of African bush elephant(left) and African forest elephant(right)

Skulls of African bush elephant(left) and African forest elephant(right)- Molar of an adult African bush elephant

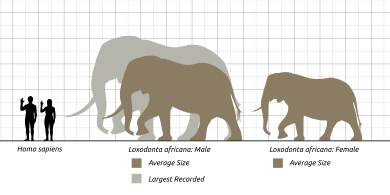

A diagram showing the average size of adult African bush elephants, with the largest recorded individual also included

A diagram showing the average size of adult African bush elephants, with the largest recorded individual also included

Molars and Trunks

African elephants utilize their long trunks and four large molars to break down and consume a large bulk of plants, shrubs, twigs, and branches. In particular, they use their trunks to strip leaves, break branches, dismantle tree bark, unearth roots, drink water, and even bathe. Without their trunks, these elephants would find their everyday routine of bathing, drinking, and eating considerably more difficult. Their molars, aiding in the consumption and digestion process, measures nearly 10 cm wide and 30 cm long, gradually withering away until the age of 15. Towards the age of 30, their baby teeth, also known as their milk teeth, are replaced by a new set which are substantially larger and stronger. As these elephants age, their teeth undergo two more stages of growth, ages 40 and 65-70, until the animal eventually dies from an inability to appropriately feed.[11]

Size

The African bush elephant is the largest and heaviest land animal on Earth, being up to 3.96 metres (13.0 ft) tall at the shoulder and 10.4 tonnes (11.5 short tons) in weight (a male shot in 1974, near Mucusso, southern Angola).[10][12] On average, males are about 3.2 metres (10.5 ft) tall at the shoulder and 6 tonnes (6.6 short tons) in weight, while females are much smaller at about 2.6 metres (8.5 ft) tall at the shoulder and 3 tonnes (3.3 short tons) in weight.[10][13][14][15] Elephants attain their maximum stature when they complete the fusion of long-bone epiphyses, occurring in males around the age of 40 and females around the age of 25.[10] Their large size means that they must consume around 50 gallons of water everyday in order to stay hydrated.[9]

Behavior

Reproduction

_calf_(17330902131).jpg)

Birthing of the African bush elephant hits its highest point just before the rainy season of each year. Females carry their young in the womb for about 22 months, known as the gestation period, and they normally give birth every five years.[16] When born, calves can almost immediately walk to maximize their chances of survival, however they tend to be dependent on their mother for a few years after birth. Newborns tend to weigh around 90–120 kg, but the average weight is around 100 kg.[17] Females also tend to reach sexual maturity at age 10, but they are most fertile from ages 25 to 45.[8] The mating system of the African bush elephant is known as androgynous (promiscuous). This type of mating includes females and males both pairing with several others at a time, also known as polygamy.[17]

Generation length of the African bush elephant is 25 years.[18]

Mating happens when the female becomes receptive, an event that can occur anytime during the year. When she is ready, she starts emitting infrasounds to attract the males, sometimes from kilometers away. The adult males start arriving at the herd during the following days and begin fighting, causing some injuries and even broken tusks. The female shows her acceptance of the victor by rubbing her body against his. They mate, and then both go their own way. After 22 months of gestation (the longest among mammals), the female gives birth to a single 90-cm-high calf which weighs more than 100 kg. The baby feeds on the mother's milk until the age of five, but also eats solid food from as early as six months old. Just a few days after birth, the calf can follow the herd by foot.[19]

Communication and adaptation

African bush elephants have long tusks, up to 3.4 metres (11 ft) in length, which are used to help them adapt to their surroundings. They use their tusks for digging, fighting, marking, and feeding, and can lift objects up to 180 kilograms (400 lb).[20] Less-aggressive elephants are known to have larger tusks, being that they will be less likely to break them since they would use their tusks in a less damaging way. The bush elephant also uses their large, flat ears to create air currents. These air currents allow them to reduce their body heat and cool off during hot seasons of the year.[21] Another cooling technique that is used is their trunk to squirt water over its body or throw dirt onto their backs to reduce sun and insect exposure. Their trunk, along with their mouth, also allows them breathe and pick up food or heavy objects.[16] Although they spend most of their time roaming to look for food, they can communicate over long distances and use vocalizations that even humans cannot hear.[8] Other ways that the elephants communicate is through changes in posture and positure and positions of the body. They present visual signals and messages through body movement, along with smell to remain in contact with other herd members.[9]

Social behavior

Females and their young live in herds of 6 to 70 members.[17] A herd is led by the eldest female, called the matriarch. Males leave the herd upon adolescence to form bachelor herds with other males of the same age. Older males lead a solitary life, approaching female herds only during the mating season. Nevertheless, elephants do not get too far from their families and recognize them when re-encountered. Sometimes, several female herds can blend for a time, reaching even hundreds of individuals.[19]

The matriarch decides the route and shows the other members of the herd all the water sources she knows, which the rest can memorize for the future. The relations among the members of the herd are very tight; when a female gives birth, the rest of the herd acknowledges it by touching her with their trunks. When an old elephant dies, the rest of the herd stays by the corpse for a while. The famous elephant graveyards are false, but these animals have recognized a carcass of their species when they found one during their trips, and even if it was a stranger, they formed around it, and sometimes they even touched its forehead with their trunks.[19]

.jpg)

_spraying_water.jpg)

.jpg) Crossing the Zambezi

Crossing the Zambezi_mating_ritual_composite.jpg)

Musth

Male elephants experience musth, a period of extreme aggression and sexual behavior accompanied with high testosterone levels, lasting a period of 1 month or less.[22] A bull in musth has been known to attack anything which disturbs him including his family members, humans, and other passive animals such as giraffes and rhinoceros.[23] In one case, a young male African bush elephant has been witnessed killing a rhinoceros during musth.[24]

Ecology

The African bush elephant is a very active and social mammal, since they are constantly on the move in search of food. Males often fight with each other during mating season, however they are considered to be very loving and caring toward relatives.[25] Bush elephants also have strong social bonds, and when their herds are faced with danger, they tend to form a close, protective circle around the young calves.[8] The elephants also tend to use their trunks to engage in physical greetings and behaviors.[9]

Range and habitat

Bush elephants are found in Sub-Saharan Africa including Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Namibia, and Angola.[8] While they inhabit primarily plains and grasslands, they can also be found in woodlands, dense forests, mountain slopes, oceanic beaches, and semi-arid deserts. They range from altitudes of sea-levels to high mountains. Increasing fragmentation of habitat is an ongoing threat to their survival.[9]

Diet

The African bush elephant is herbivorous. Its diet varies according to its habitat; elephants living in forests, partial deserts, and grasslands all eat different proportions of herbs and tree or shrubbery leaves. Elephants inhabiting the shores of Lake Kariba have been recorded eating underwater plant life.[26] To break down the plants it consumes, the African bush elephant has four large molars, two in each mandible of the jaw. Each of these molars is 10 centimetres (4 in) wide and 30 centimetres (12 in) long.

_reaching_up_3.jpg)

This species typically ingests an average of 225 kilograms (500 lb) of vegetable matter daily, which is defecated without being fully digested. That, combined with the long distances it can cover daily in search of more food, contributes notably to the dispersion of many plant seeds that germinate in the middle of a nutrient-filled feces mound. Elephants rip apart all kind of plants, and knock down trees with the tusks if they are not able to reach the tree leaves.[19] Elephants also drink great quantities of water, over 190 liters (40 imp gal; 50 U.S. gal) per day.

African elephants browse and scavenge in order to sustain their health and massive body weight. As water becomes scarce, African elephants utilize their trunks, feet, and tusks to dig holes in dry streams and lake beds to obtain fresh water.[27] Due to climatic change, the diet of the African bush elephant will vary throughout the year. During seasons of prolonged rain, the diet of these elephant’s mainly consists of grass, berries, and vegetables. During seasons of prolonged drought, African elephants will browse and consume dry leaves, small shrubs, exposed roots, and withered tree bark, accounting for up to 70 percent of their diet.[28] Due to their massive size, the consumption of every plant component, including dry leaves, small twigs, large branches, and other types of shrubs, are edible. In particular, African elephants find specific nutrients such as fatty acids and sodium through different sources of tree bark and salt licks.[8]

Predators

The adult African bush elephant generally has no natural predators due to its great size,[29] but the calves (especially the newborns) or juveniles that are vulnerable to attacks by lions (especially in the drought months) and crocodiles, and (rarely) to leopard and hyena attacks.[8] An exception to this rule was observed in Chobe National Park, Botswana, where even adults were observed to have fallen prey to lions.[30][31] Aside from that, lions in Chobe have been observed for some time taking both infants (23% of elephant kills) and juveniles. Predation, as well as drought, contribute significantly to infant mortality. The newborn elephant, known as a calf, will normally stray from the herd at birth, placing themselves and their populations into a relatively low number for their species. Over the years, certain regions in Africa have been known to contain an abundant amount of the elephant carcasses. These graveyards are overpopulated by lions and hyenas who prowl and forage for the remains of an elephant corpse.[8]

Humans are the elephant's major predator. They have been hunted for meat, skin, bones, and tusks. Trophy hunting increased in the 19th and 20th centuries, when tourism and plantations increasingly attracted sport hunters. In 1989, hunting of the African bush elephant for ivory trading was forbidden, after the elephant population fell from several million at the beginning of the 20th century to fewer than 700,000. Trophy hunting continues today. The population of African bush elephants was halved during the 1980s. Scientists then estimated, if no protective measures were taken, the wild elephant would have been extinct by 1995. The protection the elephant now receives has been partially successful, but despite increasingly severe penalties imposed by governments against illegal hunting, poaching is still common. CITES still considers this species as threatened with extinction.[32]

Threats

Poaching

The African bush elephant is categorized as a high-risk endangerment animal, with the constant threat of poaching and predators on the rise. With the high demand for ivory in Eastern Asia, the black-market trade network has left the species close to extinction. Poachers target the elephant’s tusk for the ivory, and in some cases remove the tusk while the elephant is still alive. CITES reports the black market is believed to be the main culprit for targeting around 17,000 elephants in various areas.[33] Currently the species has been pushed further into reaching the stage of extinction. Poaching of the elephant has dated back all the way to the years of 1970 and 1980, which was considered the largest killings in history. Unfortunately, the species is placed in harm's way due to the limited conservation areas provided in Africa. In most cases, the killings of the African bush elephant have occurred near the outskirts of the protected conservation sites. There has also been cases of poaching the African bush elephant for meat, which has also led to its decline.[9] Areas found mostly in Central and Western Africa contain the greatest decline in the African bush elephants. IUCN’s statistical data concludes, the population has taken a great decline of 111,000.[34]

Human disturbance

Human interference plays a major role in the drastic decline of the elephant species. Vast areas, making up Sub-Saharan Africa, were transformed to agricultural and infrastructure use. The sudden disturbance among these areas leave the elephants without a stable habitat and limits their ability to roam freely. Large corporations associated with commercial logging and mining have stripped apart the land, giving poachers easy access to the African bush elephant.[11] As human development grows, the human population faces the trouble of contact with the elephant’s more frequently, due to the species desperate need for food and water. Farmers residing in nearby areas trouble with the African bush elephants rummaging through their crops. In many cases, the elephants are killed instantly as they disturb a village or forage upon a farmer’s crop.[32]

Conservation

Legal protection

The dramatic decline of the African bush elephant has resulted in various legal protections taking place in several states of Africa. Census reports show between the years of 2007 and 2014 there has been a decrease of 30% in the elephant's population. The current rate at which the population is declining, leaves researchers to believe every year the African bush elephant will decline by 8%.[35] Certain measures focus primarily on encouraging habitat management and protection with legal action. These legal protections restrict the species from being harmed by poachers and other wildlife threats. Regions known as Range states, are responsible for ensuring certain areas inhabited by the species are preserved. The decline of the species was brought to attention worldwide in 1989. During this time, officials placed a ban stating the elephants could no longer be hunted for the ivory found in their tusks. Currently, many conservation areas are limited, and at least 70% of the species' range resides in areas which are not protected by the law.[35]

Status

The population of the African bush elephants continues to gradually decrease.[9] It has been reported that their current rate of decline is eight percent per year, mostly due to poaching.[36] In most parts of the world this species is labeled as an endangered. Since 2004, the IUCN Red List considered the elephants to be an vulnerable species.[37] On average scale there is a decline of 200,000 elephants based on the sudden increase of human populations occupying the habitats of the species. Estimates show the entire species could possibly go extinct in a decade. The debate of whether the species should fall under the classes Appendix I or Appendix II species has been argued between several regions. If a given region determines the African bush elephant to be Appendix I all international trade will be prohibited, but if the species is placed under Appendix II officials will only monitor and limit the amount of elephants traded in the black market. Areas found in Gabon and Congo are considered to contain the largest number of the African bush elephant population, while in parts of Central African Republic, the species is entirely wiped out. The IUCN monitors the elephant's population regularly to understand what conservation methods are effective and the distribution among the population. The decline is beginning to show greatly across various countries, which leaves the existence of the population in question.[37]

Conservation measures

While the species is designated as vulnerable,[38] conditions vary somewhat by region between East and Southern Africa. The populations in Southern Africa are thought to be increasing at 4% per annum whilst other populations are decreasing [38]

In 2006, an elephant slaughter was documented in southeastern Chad by aerial surveys. A series of poaching incidents, resulting in the killing of over 100 elephants, was carried out from May to August, 2006 in the vicinity of Zakouma National Park.[39] This region has a decades-old history of poaching of elephants, which has caused the population of the region, which exceeded 300,000 in 1970, to drop to about 10,000 today. The African bush elephant officially is protected by Chadian government, but the resources and manpower provided by the government (with some European Union assistance) have proven insufficient to stop the poaching.[40]

Human encroachment into or adjacent to natural areas where the African bush elephant occurs has led to recent research into methods of safely driving groups of elephants away from humans, including the discovery that playback of the recorded sounds of angry honey bees are remarkably effective at prompting elephants to flee an area.[41]

See also

References

- ↑ Shoshani, J. (2005). "Order Proboscidea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 Blanc, J. (2008). "Loxodonta africana". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2008: e.T12392A3339343. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T12392A3339343.en. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ↑ Rohland, Nadin; Reich, David; Mallick, Swapan; Meyer, Matthias; Green, Richard E.; Georgiadis, Nicholas J.; Roca, Alfred L; Hofreiter, Michael (2010). Penny, David, ed. "Genomic DNA Sequences from Mastodon and Woolly Mammoth Reveal Deep Speciation of Forest and Savanna Elephants". PLoS Biology. 8 (12) (published December 2010). p. e1000564. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000564.

- 1 2 A-Z-Animals.com. "African Bush Elephant". Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ Steenhuysen, Julie (22 December 2010). "Africa has two species of elephants, not one". Reuters.

- ↑ Nowak, Ronald M. (1999), Walker's Mammals of the World, 6th edition, Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, pp 1002.

- ↑ Yalden, D.W.; Largen, M.J.; Kock, D. (1986). "Catalogue of the Mammals of Ethiopia.6. Perissodactyla, Proboscidea, Hyracoidea, Lagomorpha, Tubulidentata, Sirenia, and Cetacea". Italian J. Zool., Suppl. 21: 31–103.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "African Bush Elephant - Loxodonta africana - Details - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "African elephant videos, photos and facts - Loxodonta africana". Arkive. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- 1 2 3 4 Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61 (3): 537–574. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014.

- 1 2 "Facts About African Elephants - The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore". The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore. Retrieved 2017-11-13.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ↑ Laws, R. M.; Parker, I. S. C. (1968). "Recent studies on elephant populations in East Africa". Symposia of the Zoological Society of London. 21: 319–359.

- ↑ Hanks, J. (1972). "Growth of the African elephant (Loxodonta africana)". East African Wildlife Journal. 10 (4): 251–272. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1972.tb00870.x.

- ↑ Laws, R.M., Parker, I.S.C., and Johnstone, R.C.B. (1975). Elephants and Their Habitats: The Ecology of Elephants in North Bunyoro, Uganda. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- 1 2 "Sedgwick County Zoo[Animals & Exhibits - Animals]". www.scz.org. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- 1 2 3 "Loxodonta africana (African bush elephant)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ Pacifici, M., Santini, L., Di Marco, M., Baisero, D., Francucci, L., Grottolo Marasini, G., Visconti, P. and Rondinini, C. (2013). "Generation length for mammals". Nature Conservation (5): 87–94.

- 1 2 3 4 "African Bush Elephant - Loxodonta africana - Details - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ "African Bush Elephant | The Nature Conservancy". www.nature.org. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ "African Bush Elephant - Facts, Lifespan, Habitat, Behavior, Pictures | Animals Adda". animalsadda.com. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ "Musth of the elephant bulls – Upali.ch". en.upali.ch. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ Georges Frei. "Musth and elephant bulls in zoo and circus". upali.ch.

- ↑ "Killing of black and white rhinoceroses by African elephants in Hluhluwe-Umfolozi Park, South Africa" by Rob Slotow, Dave Balfour, and Owen Howison. Pachyderm 31 (July–December, 2001):14–20. Accessed 14 September 2007.

- ↑ A-Z-Animals.com. "African Bush Elephant". Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ African Elephants at Animal Corner Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "African Bush Elephant - Loxodonta africana - Details - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ↑ "African Elephant". bioweb.uwlax.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ Lindsay Norwood. "ADW: Loxodonta africana: INFORMATION". Animal Diversity Web.

- ↑ Sunquist, Fiona; Sunquist, Mel (2014-10-02). "Bibliography". The Wild Cat Book: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Cats. China: University of Chicago Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-2261-4576-X.

- ↑ Power, R. J.; Compion, R. X. Shem (2009). "Lion predation on elephants in the Savuti, Chobe National Park, Botswana". African Zoology 44 (1): 36–44. doi:10.3377/004.044.0104.

- 1 2 Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, A. H.; Ehrlich, P. R. (2015). The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 102. ISBN 1421417189 – via Open Edition.

- ↑ Pallardy, Richard. "Elephant Poaching". Encyclopedia Britannica Inc.

- ↑ Mentzel, Christine. "Poaching behind worst African Elephant losses in 25 years". IUCN Report.

- 1 2 "African Elephant". www.sanbi.org. SANBI. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ↑ "Massive loss of African savannah elephants". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- 1 2 "African Elephant-Loxodonta africana". MSU Wildlife Society and Zoology Club. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- 1 2 Blanc, J. (2008). "Loxodonta africana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2008: e.T12392A3339343. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T12392A3339343.en.

- ↑ Handwerk, Brian (30 August 2006). "African Elephants Slaughtered in Herds Near Chad Wildlife Park". NationalGeographic.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2006.

- ↑ Goudarzi, Sara (30 August 2006). "100 Slaughtered Elephants Found in Africa". LiveScience.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- ↑ King, Lucy E.; Douglas-Hamilton, Iain; Vollrath, Fritz (2007). "African elephants run from the sound of disturbed bees". Current Biology. 17 (19): R832–R833. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.038. PMID 17925207.

Bibliography

- Bioexpedition (2013). Elephant Predators. Elephant-World

- Blanc, Julian (2006). African Elephant (Loxodonta africana). IUCN/SSC African Elephant Specialist Group.

- Blanc, Julian (2008) Loxodonta Africana. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Blumenbach (1797). Loxodonta Africana. ITIS Standard Report.

- Bygott, David (2013). Taxonomy Browser: Loxodonta Africana. Bold Systems

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, A. H.; Ehrlich, P. R. (2015). The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 102. ISBN 1421417189.

- Erasmus, Morkel (2014). African Elephant. National Geographic

- Estes, Richard (2007). The African Elephant. Board of Regents of University of Wisconsin: BioWeb.

- Facts About African Elephants. Maryland Zoo Press.

- Georges, Frei. Musth and Elephant Bulls in Zoo and Circus. Upali.chi.

- Goudarzi, Sara (2006). 100 Slaughtered Elephants Found In Africa. Livescience.

- Handwerk, Brian (2006). African Elephants Slaughtered in Herds Near chad Wildlife Park. NationalGeographic.

- Howard, Megan (2017). Loxodonta Africana. Animal Diversity Web.

- Jeheskel, Shoshani (2015). African Bush Elephant. Encyclopedia of Life

- Khalid, Waleed (2007). African Bush Elephant Facts. Animals Time.

- King, Lucy E.; Douglas-Hamilton, Iain; Vollrath, Fritz (2007). African Elephant Run from The Sound of Disturbed Bees. Current Biology.

- Mentzel, Christine (2016). Poaching behind worst African Elephant losses in 25 years. IUCN Report

- Norwood, Lindsay. ADW:Loxodonta Africana:Info. Animal Diversity Web.

- Nowak, Ronald M. (2008). South African Bush Elephant. Sedwick County Zoo.

- Pallardy, Richard (2013). Elephant Poaching. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc.

- Peer, J (2016). Massive Loss of African savannah Elephants. ScienceDaily.

- Pickering, Thomas (2005). Loxodonta Africana, African Elephant. Colorado State University.

- Rohland, Nadin; Reich, David; Mallick, Swapan; Meyer, Matthias; Green, Richard E.; Georgiadis, Nicholas J.; Roca, Alfred L.; Hofreiter, Michael (2010). Genomic DNA Sequence from Mastodon and Woolly Mammoth Reveal Deep speciation of Forest and Savanna Elephants. PLoS Biology.

- Shoshani, Jeheskel (2005). Order Proboscidea. Mammal Species of The World: a Taxonomic and Geographic reference. pp. 91. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Slotow,Rob, Balfour,Dave and Howison, Owen (2001). Killing of Black and White Rhinoceros by African Elephants. Pachyderm 31. pp 14–20.

- Species Sheet-Mammals Planet. Planet-mammiferes.

- Steenhuysen, Julie (2010). Africa Has Two Species,not One. Reuters.

- Yalden, D.W.; Largen, M.J.; Kock, D. (1986). Catalogue of Mammals in Ethiopia. pp. 31–103.

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole (2000) Loxodonta Africana. Smithsonian Institution Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Loxodonta africana (African Bush Elephant). |

| Wikispecies has information related to Loxodonta africana |

- Elephant Information Repository – An in-depth resource on elephants

- ARKive – images and movies of the African Bush Elephant (Loxodonta africana)

- BBC Wildlife Finder – Clips from the BBC archive, news stories and sound files of the African Bush Elephant

- View the elephant genome on Ensembl