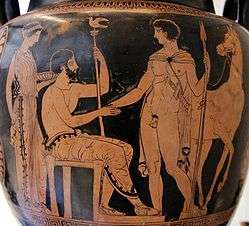

Aegeus

In Greek mythology, Aegeus (Ancient Greek: Αἰγεύς, translit. Aigeús) or Aegeas (Αιγέας, translit. Aigéas), was an archaic figure in the founding myth of Athens. The "goat-man" who gave his name to the Aegean Sea was, next to Poseidon, the father of Theseus, the founder of Athenian institutions and one of the kings of Athens.

The Myth

His reign

Upon the death of the king, Pandion II, Aegeus and his three brothers, Pallas, Nisos, and Lykos, took control of Athens from Metion, who had seized the throne from Pandion. They divided the government in four and Aegeus became king.

Aegeus' first wife was Meta,[1] and his second wife was Chalciope. Still without a male heir, Aegeus asked the oracle at Delphi for advice. Her cryptic words were "Do not loosen the bulging mouth of the wineskin until you have reached the height of Athens, lest you die of grief."[2] Aegeus did not understand the prophecy and was disappointed.

This puzzling oracle forced Aegeus to visit Pittheus, king of Troezen, who was famous for his wisdom and skill at expounding oracles. Pittheus understood the prophecy and introduced Aegeus to his daughter, Aethra, when Aegeus was drunk.[3] They lay with each other, and then in some versions, Aethra waded to the island of Sphairia (a.k.a. Calauria) and bedded Poseidon. When Aethra became pregnant, Aegeus decided to return to Athens. Before leaving, he buried his sandal, shield, and sword under a huge rock and told her that, when their son grew up, he should move the rock and bring the weapons to his father, who would acknowledge him. Upon his return to Athens, Aegeus married Medea, who had fled from Corinth and the wrath of Jason. Aegeus and Medea had one son named Medus.

Conflict with Crete

While visiting in Athens, King Minos' son, Androgeus managed to defeat Aegeus in every contest during the Panathenaic Games. Out of envy, Aegeus sent him to conquer the Marathonian Bull, which killed him.[4] Minos was angry and declared war on Athens. He offered the Athenians peace, however, under the condition that Athens would send seven young men and seven young women every nine years to Crete to be fed to the Minotaur, a vicious monster. This continued until Theseus killed the Minotaur with the help of Ariadne, Minos' daughter.

Theseus and the Minotaur

In Troezen, Theseus grew up and became a brave young man. He managed to move the rock and took his father's weapons. His mother then told him the identity of his father and that he should take the weapons back to him at Athens and be acknowledged. Theseus decided to go to Athens and had the choice of going by sea, which was the safe way, or by land, following a dangerous path with thieves and bandits all the way. Young, brave and ambitious, Theseus decided to go to Athens by land.

When Theseus arrived, he did not reveal his true identity. He was welcomed by Aegeus, who was suspicious about the stranger who came to Athens. Medea tried to have Theseus killed by encouraging Aegeus to ask him to capture the Marathonian Bull, but Theseus succeeded. She tried to poison him, but at the last second, Aegeus recognized his son and knocked the poisoned cup out of Theseus' hand. Father and son were thus reunited, and Medea was sent away to Asia.[5]

Theseus departed for Crete. Upon his departure, Aegeus told him to put up white sails when returning if he was successful in killing the Minotaur. However, when Theseus returned, he forgot these instructions. When Aegeus saw the black sails coming into Athens, mistaken in his belief that his son had been slain, he killed himself by jumping from a height : according to some, from the Acropolis or another unnamed rock[6]; according to some Latin authors, into the sea which was therefore known as the Aegean Sea.[7]

Sophocles' tragedy Aegeus has been lost, but Aegeus features in Euripides' Medea.

Legacy

At Athens, the traveller Pausanias was informed in the second-century CE that the cult of Aphrodite Urania above the Kerameikos was so ancient that it had been established by Aegeus, whose sisters were barren, and he still childless himself.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Compare Metis.

- ↑ Plutarch, Vita of Theseus; Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheke 3,15.6.

- ↑ Scholion on Euripides' Hippolytus, noted by Karl Kerenyi, The Heroes of the Greeks (1959) p 218 note 407.

- ↑ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheke 3.15.7. The identification of the festival as the Panathenaia is an interpolated anachronism.

- ↑ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Epitome of the Bibliotheke, 1.5–7; First Vatican Mythographer, 48.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus 4.61.4; Plutarch, Vita of Theseus 17 and 22; Pausanias 1.22.5; Catullus 64.215–245

- ↑ Hyginus, Fabula 41, 43; Servius on the Aeneid 3.74.

- ↑ Pausanias, 1.14.6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aegeus. |

- Theoi Project - Aegeus

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Pandion II |

King of Athens | Succeeded by Theseus |