Abolhassan Banisadr

| Abolhassan Banisadr | |

|---|---|

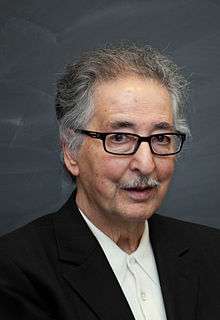

Banisadr portrait in 1980 | |

| 1st President of Iran | |

|

In office 5 February 1980 – 20 June 1981 | |

| Supreme Leader | Ruhollah Khomeini |

| Prime Minister | Mohammad-Ali Rajai |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Mohammad-Ali Rajai |

| Head of Council of the Islamic Revolution | |

|

In office 7 February 1980[1] – 20 July 1980 | |

| Preceded by | Mohammad Beheshti[1] |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs Acting | |

|

In office 12 November 1979 – 29 November 1979 | |

| Appointed by | Council of the Revolution |

| Preceded by | Ebrahim Yazdi |

| Succeeded by | Sadegh Ghotbzadeh |

| Minister of Finance | |

|

In office 12 November 1979 – 11 March 1980 | |

| Appointed by | Council of the Revolution |

| Preceded by | Ali Ardalan |

| Succeeded by | Hossein Namazi |

| Member of the Assembly of Experts for Constitution | |

|

In office 15 August 1979 – 15 November 1979 | |

| Constituency | Tehran Province |

| Majority | 1,752,816 (69.4%) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

22 March 1933 Hamadan, Iran[2] |

| Political party | Independent |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse(s) | Ozra Hosseini (m. 1961) |

| Children | 3 |

| Signature |

|

Seyyed Abolhassan Banisadr (![]()

Early life and education

Banisadr was born on 22 March 1933 in Hamedan.[4] His father was an ayatollah and close to Ruhollah Khomeini.[5] He studied finance and economics at the Sorbonne. In 1972, Banisadr's father died and he attended the funeral in Iraq where he first met Ayatollah Khomeini.[6]

Banisadr had participated in the anti-Shah student movement during the early 1960s and was imprisoned twice, and was wounded during an uprising in 1963. He then fled to France. He later joined the Iranian resistance group led by Khomeini, becoming one of his hard-liner advisors.[5][6] Banisadr returned to Iran together with Khomeini as the revolution was beginning in February 1979. He wrote a book on Islamic finance, Eghtesad Tohidi, which roughly translates as "The Economics of Monotheism."

Career

Following the Iranian Revolution, Banisadr became deputy minister of finance on 4 February 1979 and was in office until 27 February 1979. He also became a member of the revolutionary council when Bazargan and others left the council to form the interim government.[7] After the resignation of the interim finance minister Ali Ardalan on 27 February 1979, he was appointed finance minister by then prime minister Mehdi Bazargan. On 12 November 1979, Banisadr was appointed foreign minister to replace Ebrahim Yazdi in the government that was led by Council of the Islamic Revolution when the interim government resigned.

Banisadr was elected to a four-year term as president on 25 January 1980, receiving 78.9 percent of the vote in the election, and was inaugurated on 4 February. Khomeini remained the Supreme Leader of Iran with the constitutional authority to dismiss the president. The inaugural ceremonies were held at the hospital where Khomeini was recovering from a heart ailment.[8]

Banisadr was not an Islamic cleric; Khomeini had insisted that clerics should not run for positions in the government. In August and September 1980, Banisadr survived two helicopter crashes near the Iran–Iraq border. During the Iran–Iraq War, Banisadr was appointed acting commander-in-chief by Khomeini on 10 June 1981.[9]

Impeachment

The Majlis (Iran's Parliament) impeached Banisadr in his absence on 21 June 1981,[10] allegedly because of his moves against the clerics in power,[11] in particular Mohammad Beheshti, then head of the judicial system. Khomeini himself appears to have instigated the impeachment, which he signed the next day. According to Katzman, Banisadr believed the clerics should not directly govern Iran and was perceived as supporting the People's Mujahedin of Iran.[12]

Even before Khomeini had signed the impeachment papers, the Revolutionary Guard had seized the Presidential buildings and gardens, and imprisoned writers at a newspaper closely tied to Banisadr. Over the next few days, they executed several of his closest friends, including Hossein Navab, Rashid Sadrolhefazi and Manouchehr Massoudi. Ayatollah Hussein Ali Montazeri was among the few people in the government in support of Banisadr, but he was soon stripped of his powers.

At the same time, the Iranian government outlawed all political parties, except the Islamic Republic Party. Government forces arrested and imprisoned members of other parties, such as the People's Mujahedin, Fadaian Khalq, Tudeh, and Paikar.

Banisadr went into hiding for a few days before his removal, and hid in Tehran, protected by the People's Mujahedin (PMOI). He attempted to organize an alliance of anti-Khomeini factions to retake power, including the PMOI, KDP, and the Fedaian Organisation (Minority), while eschewing any contact with monarchist exile groups. He met numerous times while in hiding with PMOI leader Massoud Rajavi to plan an alliance, but after the execution on 27 July of PMOI member Mohammadreza Saadati, Banisadr and Rajavi concluded that it was unsafe to remain in Iran.[13]

In Banisadr's view, this impeachment was a coup d'état against democracy in Iran. In order to settle the political differences in the country, President Banisadr had asked for a referendum.[14]

Flight and exile

When Banisadr was impeached on 21 June 1981 he had fled and had been hiding in western Iran.[10] On 29 July, Banisadr and Masoud Rajavi were smuggled aboard an Iranian Air Force Boeing 707 piloted by Colonel Behzad Moezzi.[5] It followed a routine flight plan before deviating out of Iranian groundspace to Turkish airspace and eventually landing in Paris.[10]

Banisadr and Rajavi found political asylum in Paris, conditional on abstaining from anti-Khomeini activities in France. This restriction was effectively ignored after France evacuated its embassy in Tehran. Banisadr, Rajavi and the Kurdish Democratic Party set up the National Council of Resistance of Iran in Paris in October 1981.[5][13] However, Banisadr soon fell out with Rajavi, accusing him of ideologies favouring dictatorship and violence. Furthermore, Banisadr opposed the armed opposition as initiated and sustained by Rajavi, and sought support for Iran during the war with Iraq.

My Turn to Speak

In 1991, Banisadr released an English translation of his 1989 text My Turn to Speak: Iran, the Revolution and Secret Deals with the U.S.[15] In the book, Banisadr alleged covert dealings between the Ronald Reagan presidential campaign and leaders in Tehran to prolong the Iran hostage crisis before the 1980 U.S. presidential election.[16] He also claimed that Henry Kissinger plotted to set up a Palestinian state in the Iranian province of Khuzistan and that Zbigniew Brzezinski conspired with Saddam Hussein to plot Iraq's 1980 invasion of Iran.[15]

Lloyd Grove of The Washington Post wrote: "The book is not what normally passes for a bestseller. Cobbled together from a series of interviews conducted by French journalist Jean-Charles Deniau, it is never merely direct when it can be enigmatic, never just simple when it can be labyrinthine."[17] In a review for Foreign Affairs, William B. Quandt described the book as "a rambling, self-serving series of reminiscences" and "long on sensational allegations and devoid of documentation that might lend credence to Bani-Sadr's claims."[15] Kirkus Reviews called it "an interesting—though frequently incredible and consistently self-serving-memoir" and said "frequent sensational accusations render his tale an eccentric, implausible commentary on the tragic folly of the Iranian Revolution."[18]

Views

Banisadr, in a 2008 interview with the Voice of America on the 29th anniversary of the revolution, claimed that Khomeini is directly responsible for the violence originated from the Muslim world and that Khomeini broke his promises stated in exile after the revolution.[19] In July 2009, Banisadr publicly denounced the Iranian government's conduct after the disputed presidential election: "Khamenei ordered the fraud in the presidential elections and the ensuing crackdown on protesters." He said the government was "holding on to power solely by means of violence and terror" and accused its leaders of amassing wealth for themselves, to the detriment of other Iranians.[20]

In published articles on the 2009 Iranian election protests, he ascribed the unusually-open political climate before the election to the government's great need to prove its legitimacy.[21] However, he said the government had lost all legitimacy. The spontaneous uprising had cost the government its political legitimacy, and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei's threats led to the violent crackdown, which cost the government its religious legitimacy.

Personal life

Banisadr lives in Versailles, near Paris, in a villa closely guarded by French police.[20][21] Banisadr's daughter, Firoozeh, married Masoud Rajavi in Paris following their exile.[5][22][23] They later divorced and the alliance between him and Rajavi also ended.[5][22]

Books

- Touhid Economics, 1980

- (with Jean-Charles Deniau) My Turn to Speak: Iran, the Revolution and Secret Deals With the U.S.. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 1991. ISBN 0-08-040563-0. Translation of Le complot des ayatollahs. Paris: La Découverte, 1989.

- Le Coran et le pouvoir: principes fondamentaux du Coran, Imago, 1993

See also

References

- 1 2 Barseghian, Serge (February 2008). "مجادلات دوره مصدق به شورای انقلاب کشیده شد". Shahrvand Weekly. Institute for humanities and cultural studies (36).

- ↑ "Abolhasan Bani-Sadr PRESIDENT OF IRAN". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Houchang E. Chehabi (1990). Iranian Politics and Religious Modernism: The Liberation Movement of Iran Under the Shah and Khomeini. I.B.Tauris. p. 200. ISBN 1850431981.

- ↑ Jessup, John E. (1998). An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945-1996. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 57. – via Questia (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sreberny-Mohammadi, Annabelle; Ali Mohammadi (January 1987). "Post-Revolutionary Iranian Exiles: A Study in Impotence". Third World Quarterly. 9 (1): 108–129. doi:10.1080/01436598708419964. JSTOR 3991849.

- 1 2 Rubin, Barry (1980). Paved with Good Intentions (PDF). New York: Penguin Books. p. 308. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013.

- ↑ Metz, Helen Chapin. "The Revolution" (PDF). Phobos. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ Facts on File 1980 Yearbook, p. 88

- ↑ Mozaffari, Mahdi (1993). "Changes in the Iranian political system after Khomeini's death". Political Studies. XLI: 611–617. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1993.tb01659.x. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Sahimi, Mohammad (20 August 2013). "Iran's Bloody Decade of 1980s". Payvand. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ "Iranian presidential elections 2013: the essential guide". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Kenneth Katzman (2001). "Iran: The People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran". In Albert V. Benliot. Iran: Outlaw, Outcast, Or Normal Country?. Nova Publishers. p. 101. ISBN 1-56072-954-6.

- 1 2 Sepehr Zabih (1982). Iran Since the Revolution. Taylor & Francis. pp. 133–136. ISBN 0-7099-3000-3.

- ↑ Abolhassan, Bani-Sadr. "35 Years On, It is Time to Return to the Democratic Spirit of the Iranian Revolution". Huffington Post. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 Quandt, Walter B. (Winter 1991). "My Turn To Speak: Iran, The Revolution And Secret Deals With The U.S." Foreign Affairs. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ↑ Neil A Lewis (7 May 1991). "Bani-Sadr, in U.S., Renews Charges of 1980 Deal". New York Times. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ↑ Grove, Lloyd (May 6, 1991). "Bani-Sadr Thickens the Plot". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ↑ Abol Hassan Bani-Sadr. "My Turn to Speak: Iran, the Revolution and Secret Deals with the US". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ "Persian TV weekly highlights". Voice of America. 19 February 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Former Iran president says Khamenei behind election "fraud"". WashingtonTV. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- 1 2 Abolhassan Banisadr (3 July 2009). "The Regime Cares Nothing about Human Rights". Die Welt / Qantara. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- 1 2 Irani, Bahar (19 February 2011). "Indispensability of Examining Sexual Abuses within the Cult of Rajavi". Habilian Association. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ Smith, Craig S. (24 September 2005). "Exiled Iranians Try to Foment Revolution From France". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Abolhassan Banisadr |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abolhassan Banisadr. |

- Abolhassan Banisadr's website (in Persian)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ali Ardalan |

Minister of Finance of Iran 1979 |

Succeeded by Hossein Namazi |

| Preceded by Ebrahim Yazdi |

Minister of Foreign Affairs of Iran (Acting) 1979 |

Succeeded by Sadegh Ghotbzadeh |

| Preceded by Mohammad Beheshti |

President of the Council of Islamic Revolution 1980 |

Succeeded by Position abolished |

| New title Position established |

President of Iran 1980–1981 |

Succeeded by Mohammad-Ali Rajai |

| Military offices | ||

| Vacant Title last held by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi |

Commander-in-Chief of the Iranian Armed Forces 1980–1981 |

Succeeded by Ruhollah Khomeini |