2009 Lakewood shooting

| 2009 shooting of Lakewood, Washington police officers | |

|---|---|

The Lakewood Police Department Fallen Officer Memorial, which honors the shooting victims. | |

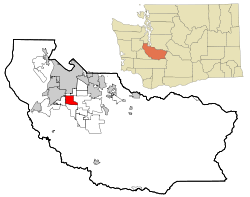

| Location | Parkland, Washington, U.S. |

| Date |

November 29, 2009 8:15 a.m. (UTC-8) |

Attack type | mass shooting |

| Weapons | Glock 17 semi-automatic pistol |

| Deaths | 4 |

| Perpetrator | Maurice Clemmons |

On November 29, 2009, four police officers of Lakewood, Washington were fatally shot at the Forza (now Blue Steele[1]) Coffee shop, located at 11401 Steele Street #108 South in the Parkland unincorporated area of Pierce County, Washington, near Tacoma. A gunman, later identified as Maurice Clemmons, entered the coffee shop, shot the officers who were working on laptops to prepare for their shifts, and fled the scene. After a two-day manhunt that spanned several cities in the Puget Sound region, Clemmons was identified on a street in south Seattle; when he refused orders to stop, he was shot and killed by a Seattle Police Department officer.

Clemmons' shooting of the Lakewood officers was initially thought to be have been part of a targeted attack by multiple persons against police officers in the Seattle-Tacoma areas, but these actions are now considered unrelated. Seattle police officer Timothy Brenton was murdered a month earlier under similar circumstances. Three weeks later on December 21 in Eatonville, two Pierce County sheriff's deputies were shot and critically injured (one later died of his wounds). That gunman was shot dead in return fire.[2] The Lakewood shooting is the most deadly attack on law enforcement in the state of Washington.

At the time, the Lakewood shooting was both the deadliest attack on law enforcement in the United States since the March 21, 2009, fatal shootings of four Oakland, California, police officers, as well as the deadliest attack on law enforcement in a single incident by a single gunman.[3] The four Lakewood police officers were the first to be killed in the line of duty since the department was established in 2004.

Immediately following the shootings, the Lakewood Police Independent Guild set up a memorial fund for the officers. As of 2012, about $3.2 million were donated to the fund. In March 2012, Lakewood police officer Skeeter Timothy Manos pleaded guilty to charges of stealing from the account, using funds for his personal use.[4]

Six people were charged in connection with the Lakewood murders. The six are friends and family of Clemmons, accused of aiding his escape and enabling him to elude capture. One was convicted in June 2010 and was sentenced to five years' imprisonment. In December 2010, three of four accused suspects were found guilty of rendering criminal assistance. In May 2011, Dorcus Allen, the last suspect and accused getaway driver, was convicted of four counts of murder. He was sentenced to 400 months in prison the following month. The June 2010 conviction was sustained on appeal. The four other convictions were all later reversed on appeal, based on the court finding misconduct by the Pierce County Prosecutor's Office, led by Mark Lindquist. Allen was granted a new trial.

Preceding the shooting

The gunman was identified as 37-year-old Maurice Clemmons, originally from Marianna, Arkansas in the Arkansas Delta. Clemmons had a violent criminal history, with at least five felony convictions in Arkansas and eight felony charges in the state of Washington. In 2000, Clemmons' 95-year sentence for aggravated robbery was commuted by Governor Mike Huckabee. After being released from prison, Clemmons moved to Western Washington in 2004, where he had family and friends.[5][6] In spring 2009, Clemmons was charged with rape of a child and third-degree assault on a Pierce County police officer.[7][8]

Clemmons was arrested on July 1, 2009, for failure to appear in court. On November 23, 2009, Clemmons paid $15,000 for a $190,000 bail bond from a Chehalis-based company, to secure his release. He was released on bail November 22, a week before the shootings, after posting a $150,000 bail bond.[7] Two other bail bond agencies had rejected Clemmons based on his history of failing to appear in court.

Clemmons failed to check in as required with his community corrections officer within 24 hours of his release, but police took no action.[9] On November 26, 2009,[10][11] during a Thanksgiving gathering at the home of Clemmons's aunt, he told several people that he was angry about his Pierce County legal problems. He said that he intended to shoot and kill police officers and others, including school children. He showed a gun to the people in the room and told them he had two others in his car and home.

Clemmons said he planned to remove his court-ordered ankle monitor to trigger an alarm, and shoot police officers who responded by coming to his house.[12][13] Dorcus Allen, a convicted murderer who had previously served in an Arkansas prison with Clemmons, was allegedly present for this conversation.[12] Clemmons cut off the GPS monitor on Thanksgiving.[9] On November 28, Clemmons showed two handguns to friends Eddie and Douglas Davis and told them he planned to shoot police officers; the exchange was witnessed by Clemmons's half-brother Rickey Hinton, with whom he shared a house.[14] He told the men he had already twice tried to go to a Tacoma police station, where he planned to walk in and start shooting. He also talked about stopping at a crowded intersection or a school and shooting people there.[9]

Incident

Shooting

On the morning of Sunday, November 29, 2009, the four officers were working on their laptops at a Forza Coffee Company coffee shop prior to the start of their shift in nearby Parkland, next to McChord Air Force Base. All four were armed and in full uniform, wearing bulletproof vests.[15][16][17] Clemmons drove a white pickup truck to Allen's home, and Allen drove him past the coffee shop. After they saw marked police patrol cars in the parking lot, Allen drove back past the coffee shop and parked nearby.[12][13]

At approximately 8:15 AM (UTC-8), Clemmons entered the coffee shop, approached the counter, turned around, and opened fire on the four seated officers with a Glock 17 9mm semi-automatic handgun. He also carried a Smith & Wesson .38-caliber revolver. Sergeant Mark Renninger and Officer Tina Griswold were shot in the head and killed while sitting. Officer Ronald Owens was shot in the neck as he stood up and attempted to draw his weapon. Officer Greg Richards fired his own weapon and hit Clemmons in the abdomen, before succumbing to a shot to the head. Clemmons stole Richards's Glock before fleeing the scene with Allen.[15][18][19] Clemmons did not shoot or attack anyone else, nor did he take any money from the cash register. Investigators said the murders were an attack against police officers in general, since none of the four officers was individually targeted, and robbery was ruled out as a motive.[20] Allen later told detectives he stopped at an intersection and abandoned Clemmons and the truck, claiming he "wanted of no part of this". But, police disputed his claim and said there was no evidence Allen had abandoned the vehicle.[12][13]

Manhunt

The afternoon following the shooting, the Pierce County sheriff identified Maurice Clemmons as the suspected murderer, saying that he had a long, violent, criminal history in Arkansas and Washington. Police confirmed that Clemmons had been shot in the abdomen during the attack, and advised hospitals to be aware.

In the late evening hours of November 29, Seattle police believed they had Clemmons surrounded in a home in the Leschi area of Seattle. With air support provided by King County Sheriff's Office, SWAT teams from the King County Sheriff's Office, Seattle Police Department, Tacoma Police Department, and other agencies entered the home after a twelve-hour standoff, but they found no one inside. Earlier in the day, Tacoma police served a search warrant on a Tacoma home belonging to a "person of interest" and collected evidence.[21][22] An intense manhunt ensued, and police from agencies in Pierce and King counties conducted searches at the University of Washington campus, Rizal Park, and in Renton, without success. Acting on a tip, King County Sheriff's Deputies and Washington State Patrol troopers were also conducting surveillance and going door to door at Snoqualmie Pass-area homes, 50 miles (80 km) east of Seattle. After hours of investigating, that search was called off.

The tip had been one of thousands received by local law enforcement agencies. The police were offering a $145,000 reward for information leading to Clemmons's arrest.[8][15]

Apprehension and death of Clemmons

Around 2:45 a.m. on December 1, Seattle police officer Benjamin L. Kelly was on patrol in south Seattle; he came upon a 1990 Acura Integra parked on the street at 44th Place South and South Kenyon Street. It was empty but the hood was raised and the engine running.[23] He ran the vehicle's license plate number and determined that it had been stolen about two hours earlier.[23] While sitting in his patrol car to report the stolen vehicle, Kelly noticed a man matching Clemmons' description approaching him from behind,[23] walking first on the sidewalk and then in the middle of the street.[24] Police accounts state that Kelly confronted Clemmons and ordered him to stop and show his hands, but Clemmons began to flee around the disabled vehicle and reportedly "reached into his waist area and moved" as Kelly was drawing his side arm.[25][26] Kelly fired three shots at Clemmons, followed by another four shots as the suspect ran away "in a dead sprint,"[24] and struck him at least twice.[27]

Clemmons reached the sidewalk and collapsed face-down in a walkway leading to a home on Kenyon Street. Kelly retreated behind his patrol car, retrieved his shotgun, and called for backup.[24] Within moments, Seattle police came to the scene. A team of officers approached the suspect, handcuffed him, and dragged him away from the home. Seattle Fire Department medics responded and pronounced the suspect dead at the scene.[27] Seattle police later identified the deceased suspect as Clemmons. He was allegedly carrying a handgun identified as having belonged to officer Greg Richards, the fourth fatality in the Lakewood shooting.[25] Clemmons had a recent bullet wound to his abdomen, which had been stuffed with cotton and gauze and sealed with duct tape. The police determined the wound was sustained in the Lakewood shooting.[27]

Victims

All four officers had been with the Lakewood Police Department from its beginning in 2004. They were:[28][29]

- Sergeant Mark Renninger, 39, thirteen years in law enforcement; died from a gunshot wound to the head.[30]

- Officer Ronald Owens, 37, twelve years in law enforcement, from Puyallup; died from a gunshot wound to the neck.[30]

- Officer Tina Griswold, 40, fourteen years of law enforcement; died from a gunshot wound to the head.[30]

- Officer Greg Richards, 42, eight years of law enforcement experience, from Graham; died from a gunshot wound to the head.[30]

Aftermath

Weapons

Federal authorities ran traces on a 9mm Glock Model 17 and a Smith & Wesson .38-caliber revolver:

- The Glock was purchased in June 2005 at a Renton, Washington pawnshop. The purchaser reported the gun stolen in March 2006, after his car was broken into at a downtown Seattle parking garage at Second Avenue and James Street.

- The Smith & Wesson revolver was shipped in 1981 to the (now-closed) Police Arms and Citizen Supply in Lakewood, Colorado, but from that point, no details were found.[27]

- A Glock .40 caliber handgun was also used when this gun was taken from one of the police officers. <http://www.historylink.org/File/9677>

Accomplices

By December 2, 2009, six individuals were arrested and faced charges of providing assistance to Clemmons before and after the shooting.[27] Darcus Allen was identified as wanted in connection with a bank robbery in Arkansas – he had served time with Clemmons in an Arkansas prison and is believed to have been Clemmons's getaway driver.[31] The other five were accused of providing such assistance to Clemmons as transporting him to several locations, providing him with money and cell phones, making arrangements for him to flee the state, and treating his gunshot wound from the Lakewood shooting, all with full knowledge of the crime he had committed.[27][31] In June 2010, Clemmons's sister, LaTanya, was sentenced to five years imprisonment for acting as a getaway driver after the shooting. In December 2010, three of the four other suspects were convicted.[32] On January 14, 2011, Pierce County Superior Court Judge Stephanie Arend sentenced accomplices Eddie Lee Davis to 10 years, five months; Douglas Edward Davis to seven years, six months; and Letrecia Nelson to six years, two months in state prison. Ricky Hinton was acquitted of all charges.[33] All of these convictions and sentences, except for LaTanya Clemmons' sentence, were reversed by the Washington Supreme Court in appeals of 2013 and 2014 because of prosecutor misconduct in the original trials.[34]

In May 2011, Allen, the remaining suspect, was convicted of four counts of murder as the getaway driver for Clemmons. He was sentenced to 420 years in prison the following month.[35] In January 2015, the Washington Supreme Court overturned his conviction and ordered a new trial, citing prosecutor misconduct similar to the earlier reversals, with a new trial granted.[34]

After being convicted in the retrial and sentenced, Allen's sentence was reversed on appeal. The court cited that he could not be tried for the same crime, citing double jeopardy. That decision was appealed by the state, which held that at the first trial he was not charged with a capital crime, because he was the getaway driver.[36]

Political

Mike Huckabee was widely criticized for having commuted Clemmons' sentence and allowed his release from prison in 2000.[11][37] The evening of the shooting, Huckabee released a statement noting the roles of the parole board that freed him and the criminal justice system, which Huckabee said had repeatedly failed to properly handle Clemmons.[38][39]

In his statement, Huckabee said, "Should he be found to be responsible for this horrible tragedy, it will be the result of a series of failures in the criminal justice system in both Arkansas and Washington State."[38] Huckabee, who was considered a favorite for the Republican Party presidential nomination in 2012,[40] claimed that the situation was used as a political weapon against him.[37] Clemmons has been compared to Willie Horton,[40][41] a convicted felon who was furloughed from a Massachusetts prison in 1986 but never returned and committed more violent crimes several months later. The Horton case eventually factored into the 1988 presidential campaign of Democratic Party candidate Michael Dukakis, who was Governor of Massachusetts at the time and supported the furlough program. Timothy Egan, opinion writer for The New York Times, said of Huckabee's role in Clemmons's release, "If this case does not sink the presidential aspirations of Huckabee…it should."[11]

In his book about the shooting, The Other Side of Mercy, Jonathan Martin of The Seattle Times wrote that Huckabee apparently failed to review Clemmons' prison file, which was "thick with acts of violence and absent indications of rehabilitation." Martin also suggested that Huckabee failed to ensure Clemmons' post-release plan was "solid, or even factual." In an article for the Times, Martin wrote that if Huckabee was serious about running for president in 2016, "he'll have to answer his Maurice Clemmons problem."[42]

Some university professors, criminologists, and attorneys speculated that U.S. governors will become more reluctant to grant pardons and clemencies to convicted felons, in order to avoid the negative publicity faced by Dukakis and Huckabee in the Horton and Clemmons cases, respectively.[41]

According to several witnesses, local elected prosecutor Mark Lindquist said that the mass-murder was worth "$100,000 of free publicity" in a campaign to re-elected him.[43]

Officers' memorial service

A public memorial service for the four slain officers was held December 8, 2009, at the Tacoma Dome.[44] The day began with a 10-mile (16 km) procession from McChord Air Force Base past the Lakewood police station to the Tacoma Dome. Over 2,000 police and fire vehicles from over 150 different law enforcement and fire agencies participated in the procession, which took five hours to complete.[45] Over 20,000 people, mostly from the law enforcement and firefighting communities, attended the service at the Tacoma Dome.[46] Police officers from as far away as New York City and Boston, as well as a large contingent of Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers, were in attendance.[46] Lakewood's mayor and police chief gave remarks at the service, followed by eulogies by family, friends, and colleagues of the four officers. Washington Governor Christine Gregoire also spoke, saying, "We will remember them today. We will remember them always."[47] The service concluded with a played recording of a police dispatcher attempting to call each officer with no response, and the dispatcher declaring each officer as "gone but not forgotten."[48] The officers' remains were buried in private ceremonies by their individual families.

From a logistical standpoint, the agencies preparing for the memorial services expected 20,000 law enforcement personnel to appear at the service. One thousand emergency vehicles and police cruisers were set up to follow the families of the victims to the Tacoma Dome. Fifty people from several public agencies worked to make the event occur smoothly. Jody Woodcock, a program manager of the Pierce County Department of Emergency Management, said that the agencies planned to make the event look like it was easily prepared and that the authorities intend to "take care of all the details so the families and the law enforcement community don't have to think about them." Rob Carson of The (Tacoma) News Tribune said, "Logistically, the event is staggering in its complexity." Alaska Airlines gave airline tickets to family members who were going to the event and were flying into Seattle-Tacoma International Airport from other states. The American Red Cross donated food and water for the event.[49] After action report was presented by Detective Jeff Paynter,[50] Officer Brian Markert, Officer Michael L. O'Neill, and Assistant Chief Michael Zaro, according to which :-

"This incident was akin to a suicide bomber walking into a coffee shop and, without notice, detonating an explosive. The difference here is there were specific victims targeted and the suspect did not die in the attack."[51]

The site of the shooting reopened two weeks after the shooting (which has since changed its name to Blue Steele Coffee Company following a change in ownership), and a memorial to the slain officers remains there to this day.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 Champaco, Brent (2014-08-24). "Blue Steele Coffee Company Up For Best Coffeehouse In The West". Patch.com. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ↑ Perry, Nick (21 December 2009). "Family had sought protection from man suspected of shooting deputies". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ↑ "4 Lakewood officers slain; hunt is on for gunman". The Seattle Times. 2009-11-29. Archived from the original on 2009-12-02. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ↑ "Top Sentence Sought for Ex-Lakewood Cop Who Stole Donations", by Adam Lynn, 26 June 2012, The News Tribune

- ↑ Schone, Mark. "Huckabee Helped Set Rapist Free Who Later Killed Missouri Woman". ABC News. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ Buck, Michael (2009-11-30). "Slain cop a Valley native". The Express-Times. Easton, Pennsylvania. p. A1.

- 1 2 "Suspect let out of Pierce County jail one week ago". The Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington. 2009-11-29. Archived from the original on 2009-12-03. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- 1 2 "Police conducting several "tactical operations" now in search for shooting suspect". The Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington. 2009-11-29. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- 1 2 3 Martin, Jonathan; Armstrong, Ken (October 21, 2010). "Maurice Clemmons eyed police station as a target, too". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Suspect let out of Pierce County jail one week ago". The Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington. 2009-11-29. Archived from the original on 2009-12-03. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- 1 2 3 Egan, Timothy (2009-11-30). "Mike Huckabee's Burden". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Lynn, Adam (March 3, 2010). "Prosecutors say Allen knew of Clemmons' plan". The News Tribune. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Alleged getaway driver in officer slayings charged with murder". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. March 2, 2010. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ↑ Netter, Sarah (2009-12-02). "Helping a Cop Killer: Maurice Clemmons' Friends, Family Busted". ABC News. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Gene (2009-11-29). "Official: 4 police officers shot dead in Wash". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Miletich, Steve; Sara Jean Green (2009-11-29). "Four police officers shot to death in Lakewood in apparent ambush". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2009-12-02. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ↑ "4 police officers killed in Wash. coffee shop". MSNBC. 2009-11-29. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ↑ "Dispatches on the Lakewood police shooting and manhunt". The Seattle Times. 2009-11-29. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ↑ Mulick, Stacey (2009-12-01). "Lakewood officer who shot suspect Clemmons identified". The News Tribune (Tacoma). Archived from the original on 2009-12-03. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ "Shooting of four Lakewood officers 'an execution': Washington police". Vancouver Sun. 2009-11-29. Archived from the original on 2009-12-02. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ↑ "Police surround Seattle home where person of interest in police shooting may be hiding". The Seattle Times. 2009-11-29.

- ↑ Oppmann, Patrick; Peter Hamby; Samira Simone; Dave Alsup; Dina Majoli (2009-11-29). "Man sought in deadly ambush had prison sentence commuted". CNN. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- 1 2 3 Miletich, Steve; Jack Broom (2 December 2009). "Routine stolen-car check led to Lakewood police-slaying suspect". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 Sullivan, Jennifer; Martin, Jonathan (5 April 2010). "Officer says he feared for his life when Clemmons refused orders". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- 1 2 Sullivan, Jennifer; Mark Rahner; Jack Broom (1 December 2009). "Lakewood police shooting suspect killed by Seattle police officer in South Seattle early this morning". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ↑ Johnson, Gene (2009-12-01). "Sheriff's spokesman: Police fatally shoot suspect". Yahoo! News.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Team Of Accused Accomplices Rises To 6". Seattle: KIRO-TV. 2 December 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-12-03. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ "Slain Lakewood police officers are identified". The Seattle Times. 2009-11-29. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ↑ "Slain Lakewood officers leave holes in community fabric". The Seattle Times. 2009-11-30. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- 1 2 3 4 Peter Callaghan. "Prosecutor gives first details of crime scene". The News Tribune. Archived from the original on 2009-12-04. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- 1 2 Milletich, Steve; Mike Carter (2 December 2009). "Alleged getaway driver in officers' slaying could face murder charges". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ Martin, Johnathon (June 17, 2010). "Clemmons Sister sentenced to five years in prison". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ writer, ADAM LYNN; Staff. "Maurice Clemmons' associates sentenced".

- 1 2 Carter, Mike (2015-01-15). "Lakewood cop killer's getaway driver to get new trial, court rules". The Seattle Times.

- ↑ Martin, Jonathan (2011-06-17). "Maurice Clemmons' getaway driver sentenced to 420 years in prison". The Seattle Times.

- ↑ Lynn, Adam (25 October 2017). "Cop killer's alleged driver wins another appeal, can't be charged with aggravated murder". The News Tribune. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- 1 2 Brunner, Jim; Kelleher, Susan (2009-11-30). "Persuasive appeal helped Clemmons win clemency". The Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington. Archived from the original on 2009-12-04. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- 1 2 Franke-Ruta, Garance (2009-11-30). "Huckabee commuted sentence of suspect in Washington police slayings". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ Montopoli, Brian (2009-11-30). "Mike Huckabee Granted Clemency to Maurice Clemmons". CBS News. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- 1 2 DeMillo, Andrew (1 December 2009). "Political death blow for Huckabee?". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- 1 2 Chen, Stephanie (2009-12-02). "Seattle shootings may reduce pardons and commutations". CNN.com. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ Martin, Jonathan (2013-12-18). "Mike Huckabee's Maurice Clemmons problem". The Seattle Times.

- ↑ "Report of Investigation" (PDF). Sebris Busto James.

- ↑ Seattle Times staff (1 December 2009). "Memorial for slain officers to be next Tuesday at Tacoma Dome". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ "Big police procession in Tacoma for slain officers". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. 8 December 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- 1 2 Seattle Times Staff (9 December 2009). "Officers' service steeped in tradition, brotherhood". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ↑ "20,000 pay tribute to slain law officers". 9 December 2009.

- ↑ "Updates from Lakewood police memorial". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ↑ Carson, Rob. "Over 20,000 expected at tribute to slain officers." The Seattle Times. December 6, 2009. Retrieved on December 14, 2009.

- ↑ Detective Jeff Paynter

- ↑ Remembering the Lakewood Four

External links

Coordinates: 47°9′9.85″N 122°28′2.71″W / 47.1527361°N 122.4674194°W