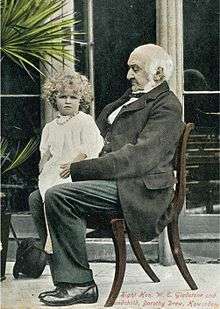

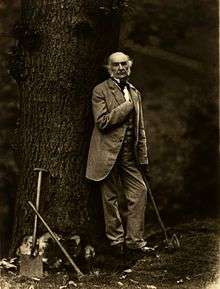

William Ewart Gladstone (29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British Liberal politician and Prime Minister (1868–1874, 1880–1885, 1886 and 1892–1894). He was a notable political reformer, known for his populist speeches, and was for many years the main political rival of Benjamin Disraeli.

Quotes

1840s

- I have already expressed my opinion that the interference of the noble Lord should have been for the suppression of the trade in opium, and that the war was not justified by any excesses committed on the part of the Chinese. I have already stated, that although the Chinese were undoubtedly guilty of much absurd phraseology, of no little ostentatious pride, and of some excess, justice, in my opinion, is with them, and, that whilst they, the Pagans, and semi-civilized barbarians, have it, we, the enlightened and civilized Christians, are pursuing objects at variance both with justice, and with religion.

- Speech in the House of Commons (8 April 1840) against the First Opium War.

- Ireland, Ireland! That cloud in the west! That coming storm! That minister of God's retribution upon cruel, inveterate, and but half-atoned injustice! Ireland forces upon us those great social and great religious questions—God grant that we may have courage to look them in the face, and to work through them.

- Letter to his wife, Catherine Gladstone (12 October 1845), quoted in John Morley, The Life of Wiliam Ewart Gladstone: Volume I (London: Macmillan, 1903), p. 383.

1850s

- This is the negation of God erected into a system of Government.

- A letter to the Earl of Aberdeen, on the state prosecutions of the Neapolitan government (7 April 1851), p. 9.

- From the ancient strife of territorial acquisition we are labouring, I trust and believe, to substitute another, a peaceful and a fraternal strife among nations, the honest and the noble race of industry and art.

- An Examination of the official reply of the Neapolitan Government (London: John Murray, 1852), p. 50.

- ...if it be true that, at periods now long past, England has had her full share of influence in stimulating by her example the martial struggles of the world, may she likewise be forward, now and hereafter, to show that she has profited by the heavy lessons of experience, and to be—if, indeed, in the designs of Providence, she is elected to that office—the standard-bearer of the nations upon the fruitful paths of peace, industry, and commerce.

- An Examination of the official reply of the Neapolitan Government (London: John Murray, 1852), p. 50.

- When we speak of general war, we don't mean real progress on the road of freedom, the real, moral, and social advancement of man, achieved by force. This may be the intention, but how rarely is it the result of general war! We mean this:—That the face of nature is stained with human gore—we mean that taxation is increased and industry diminished—we know that it means that burdens unreasonable and untold are entailed on late posterity—we know that it means that demoralization is let loose, that families are broken up, that lusts become unbridled in every country to which that war is extended.

- Speech at Manchester (12 October 1853), quoted in The Times (13 October 1853), p. 7.

- All the terms that we demanded have, since the war began, been substantially conceded...My hon. Friend...[said] that we must obtain a success in order that we may secure better terms; but that is not the public and popular sentiment; the popular feeling is, that as to terms there is no great matter at issue, but that what you want is more military success...It is not only indefensible—it is hideous, it is anti-Christian, it is immoral, it is inhuman; and you have no right to make war simply for what you call success. If, when you have obtained the objects of the war, you continue it in order to obtain military glory...I say you tempt the justice of Him in whose hands the fates of armies are as absolutely lodged as the fate of the infant slumbering in its cradle; you tempt Him to launch upon you His wrath; and if this be courage, I, for one, have no courage to enter upon such a course. I believe it to be alike guilty and unwise.

- Speech in the House of Commons (24 May 1855) on the Crimean War.

- At a time when sentiments are so much divided, every man I trust, will give his vote with the recollection and the consciousness that it may depend upon his single vote whether the miseries, the crimes, the atrocities that I fear are now proceeding in China are to be discountenanced or not. We have now come to the crisis of the case. England is not yet committed. But if an adverse vote be given...England will have been committed. With you then, with us, with every one of us, it rests to show that this House, which is the first, the most ancient, and the noblest temple of freedom in the world, is also the temple of that everlasting justice without which freedom itself would be only a name or only a curse to mankind. And I cherish the trust and belief that when you, Sir, rise in your place to-night to declare the numbers of the division from the chair which you adorn, the words which you speak will go forth from the walls of the House of Commons, not only as a message of mercy and peace, but also as a message of British justice and British wisdom, to the farthest corners of the world.

- Speech in the House of Commons (3 March 1857) against the Second Opium War.

- Decision by majorities is as much an expedient, as lighting by gas.

- Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age (Oxford University Press, 1858), p. 116.

- Economy is the first and great article (economy such as I understand it) in my financial creed. The controversy between direct and indirect taxation holds a minor, though important place.

- Letter to his brother Robertson of the Financial Reform Association at Liverpool (1859), as quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 241

- What has been the state of things since 1853? It is useless to blink the fact that not merely within the circle of the public departments and of Cabinets, but throughout the country at large, and within the precincts of this House—the guardians of the purse of the people—the spirit of public economy has been relaxed; charges upon the public funds of every kind have been admitted from time to time upon slight examination; every man's petition and prayer for this or that expenditure has been conceded with a facility which I do not hesitate to say you have only to continue for some five or ten years longer in order to bring the finances of the country into a state of absolute confusion.

- Speech in the House of Commons (21 July 1859) against Benjamin Disraeli's Budget.

1860s

- I am certain, from experience, of the immense advantage of strict account-keeping in early life. It is just like learning the grammar then, which when once learned need not be referred to afterwards.

- Letter to Mrs. Gladstone (14 January 1860), as quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 242

- Sir, there was once a time when close relations of amity were established between the Governments of England and France. It was in the reign of the later Stuarts; and it marks a dark spot in our annals, because it was an union formed in a spirit of domineering ambition on the one side, and of base and vile subserviency on the other. But that, Sir, was not an union of the nations; it was an union of the Governments. This is not be an union of the Governments; it is to be an union of the nations.

- Speech in the House of Commons (10 February 1860) on the Anglo-French Commercial Treaty

- ...the right hon. Gentleman the Member for Stroud says of this Budget...[that] it is a mortal stab at the Constitution. I want to know to what Constitution does it give a mortal stab? In my opinion it gives no mortal stab, and no stab at all. But, on the contrary, so far as it alters anything in the most recent practice, it alters in the direction of restoring that good old Constitution which took its root in Saxon times, which grew under the Plantagenets, which endured the hard rule of the Tudors, and resisted the aggressions of the Stuarts, and which has now come to such perfect maturity under the rule of the House of Brunswick.

- Speech in the House of Commons (16 May 1861)

- We may have our own opinions about slavery; we may be for or against the South; but there is no doubt that Jefferson Davis and other leaders of the South have made an army; they are making, it appears, a navy; and they have made what is more than either—they have made a Nation... We may anticipate with certainty the success of the Southern States so far as regards their separation from the North. I cannot but believe that that event is as certain as any event yet future and countingent can be.

- Speech on the American Civil War, Town Hall, Newcastle upon Tyne (7 October 1862), quoted in The Times (9 October 1862), pp. 7-8.

- I mean this, that together with the so-called increase of expenditure there grows up what may be termed a spirit which, insensibly and unconsciously perhaps, but really, affects the spirit of the people, the spirit of parliament, the spirit of the public departments, and perhaps even the spirit of those whose duty it is to submit the estimates to parliament.

- Speech in the House of Commons (16 April 1863), quoted in The Life of William Ewart Gladstone. Volume II (1903) by John Morley, p. 62

- But how is the spirit of expenditure to be exorcised? Not by preaching; I doubt if even by yours. I seriously doubt whether it will ever give place to the old spirit of economy, as long as we have the income-tax. There, or hard by, lie questions of deep practical moment.

- Letter to Richard Cobden (5 January 1864), quoted in The Life of William Ewart Gladstone Volume II (1903) by John Morley, p. 62

- I venture to say that every man who is not presumably incapacitated by some consideration of personal unfitness or of political danger is morally entitled to come within the pale of the Constitution. ...fitness for the franchise, when it is shown to exist—as I say it is shown to exist in the case of a select portion of the working class—is not repelled on sufficient grounds from the portals of the Constitution by the allegation that things are well as they are. I contend, moreover, that persons who have prompted the expression of such sentiments as those to which I have referred, and whom I know to have been Members of the working class, are to be presumed worthy and fit to discharge the duties of citizenship, and that to admission to the discharge of those duties they are well and justly entitled.

- Speech in the House of Commons (11 May 1864)

- At last, my friends, I am come amongst you. And I am come…unmuzzled.

- Speech to the electors of South Lancashire. (18 July 1865)

- I am a member of a Liberal Government. I am in association with the Liberal party. I have never swerved from what I conceived to be those truly Conservative objects and desires with which I entered life. I am, if possible, more fondly attached to the institutions of my country than I was when as a boy I wandered among the sand-hills of Seaforth or the streets of Liverpool. But experience has brought with it its lessons. I have learnt that there is wisdom in a policy of trust, and folly in a policy of mistrust. I have not refused to receive the signs of the times. I have observed the effect that has been produced by Liberal legislation, and if we are told...that all the feelings of the country are in the best and broadest sense Conservative,—that is to say, that the people value the country and the laws and institutions of the country; if we are told that, I say honesty compels us to admit that result has been brought about by Liberal legislation.

- Speech at Liverpool (18 July 1865), quoted in The Times (19 July 1865), p. 11.

- The position of England, gentlemen, is a peculiar position in the world. England has inherited from bygone ages more, perhaps, of what was most august and venerable in those ages than any other European country, and at the same time that her traditions of the past are so rich and fruitful that all our minds and all our characters have both within our knowledge and beyond our knowledge been largely moulded by them. ... geographically she stands with Europe on one side of her and America on the other, so she stands between those feudal institutions in which European society was formed, and which have given her hierarchy of class, and on the other side those principles of equality forming the basis of society in America.

- Speech to the Liverpool Liberal Association (6 April 1866), quoted in The Times (7 April 1866), p. 9.

- ...there appeared to me to have grown up under the present Government a system of what I called, in regard to the public expenditure, making things pleasant all round. That means going from town to town, granting what this community wants, granting what that community wants, granting what the other community wants, and leaving out of sight that huge public which unfortunately has not got the voices and the advocates ready always to defend it against these local and particular claims, but of which it is our highest boast that we seek to be the advocates and the champions.

- Speech in Leigh, Lancashire (20 October 1868), quoted in The Times (21 October 1868), p. 11.

- If you want to be served you must draw the distinction between those who want to serve you and those who don't, and if the electors of South Lancashire and of the country generally are contented to allow this method of expenditure to go on, this Continental system of feeding the desires of classes and portions of the community at the expense of the whole—it is idle for you to satisfy yourselves with vague and general promises. ... If that is to be the system on which public finance is to be administered you must be prepared to resign all hopes of remission of taxation, even in good years, and in bad years you must look for a steady augmentation of the income-tax.

- Speech in Leigh, Lancashire (20 October 1868), quoted in The Times (21 October 1868), p. 11.

- ...we find and we know that this attempt in Ireland to make the power and influence of the State the means of supporting one creed against another has been the plague and the scourge of the country—has divided man from man, class from class, kingdom from kingdom, and in this great, and ancient, and noble empire has had the effect of now exhibiting us to the world as a divided country—three kingdoms, two of which we are indeed heartily united and associated, but the third of which offers to mankind a spectacle painful and full of schism and destruction within itself, and alienation and estrangement as regards the Throne and Constitution of this realm.

- Speech in the assembly-rooms at Wavertree (14 November 1868), quoted in The Times (16 November 1868), p. 5

- The only means which have been placed in my power of "raising the wages of colliers" has been by endeavouring to beat down all those restrictions upon trade which tend to reduce the price to be obtained for the product of their labour, & to lower as much as may be the taxes on the commodities which they may require for use or for consumption. Beyond this I look to the forethought not yet so widely diffused in this country as in Scotland, & in some foreign lands; & I need not remind you that in order to facilitate its exercise the Government have been empowered by Legislation to become through the Dept. of the P.O. the receivers & guardians of savings.

- Letter to Daniel Jones, an unemployed collier who complained of unemployment and of low wages (20 October 1869) as quoted in The Gladstone Diaries: With Cabinet Minutes and Prime-ministerial Correspondence: 1869-June 1871 Vol. 7 (1982) by H. C. G. Matthew, p. lxxiv

1870s

- Hephaistos bears in Homer the double stamp of a Nature-Power, representing the element of fire, and of an anthropomorphic deity who is the god of art at a period when the only fine art known was in works of metal produced by the aid of fire.

- Jeventus Mundi: The Gods and Men of the Heroic Age (1870) p. 289.

- I am inclined to say that the personal attendance and intervention of women in election proceedings, even apart from any suspicion of the wider objects of many of the promoters of the present movement, would be a practical evil not only of the gravest, but even of an intolerable character.

- Speech in the House of Commons (3 May 1871) on the Women's Disabilities Bill.

- They are not your friends, but they are your enemies in fact, though not in intention, who teach you to look to the Legislature for the radical removal of the evils that afflict human life...It is the individual mind and conscience, it is the individual character, on which mainly human happiness or misery depends. (Cheers.) The social problems that confront us are many and formidable. Let the Government labour to its utmost, let the Legislature labour days and nights in your service; but, after the very best has been attained and achieved, the question whether the English father is to be the father of a happy family and the centre of a united home is a question which must depend mainly upon himself. (Cheers.) And those who...promise to the dwellers in towns that every one of them shall have a house and garden in free air, with ample space; those who tell you that there shall be markets for selling at wholesale prices retail quantities—I won't say are imposters, because I have no doubt they are sincere; but I will say they are quacks (cheers); they are deluded and beguiled by a spurious philanthropy, and when they ought to give you substantial, even if they are humble and modest boons, they are endeavouring, perhaps without their own consciousness, to delude you with fanaticism, and offering to you a fruit which, when you attempt to taste it, will prove to be but ashes in your mouths. (Cheers.)

- Speech at Blackheath (28 October 1871), quoted in The Times (30 October 1871), p. 3.

- The idea of abolishing Income Tax is to me highly attractive, both on other grounds & because it tends to public economy.

- Letter to H. C. E. Childers (3 April 1873)

- Individual servitude, however abject, will not satisfy the Latin Church. The State must also be a slave.

- Pamflet The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance: A Political Exposition (November 1874), quoted in All Roads lead to Rome? The Ecumenical Movement (2004) by Michael de Semlyen.

- The operations of commerce are not confined to the material ends; that there is no more powerful agent in consolidating and in knitting together the amity of nations; and that the great moral purpose of the repression of human passions, and those lusts and appetites which are the great cause of war, is in direct relation with the understanding and application of the science which you desire to propagate.

- Speech to the Political Economy Club (31 May 1876) upon the centenary of Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations.

- I am delighted to see how many young boys and girls have come forward to obtain honourable marks of recognition on this occasion, — if any effectual good is to be done to them, it must be done by teaching and encouraging them and helping them to help themselves. All the people who pretend to take your own concerns out of your own hands and to do everything for you, I won't say they are imposters; I won't even say they are quacks; but I do say they are mistaken people. The only sound, healthy description of countenancing and assisting these institutions is that which teaches independence and self-exertion... When I say you should help yourselves — and I would encourage every man in every rank of life to rely upon self-help more than on assistance to be got from his neigbours — there is One who helps us all, and without whose help every effort of ours is in vain; and there is nothing that should tend more, and there is nothing that should tend more to make us see the beneficence of God Almighty than to see the beauty as well as the usefulness of these flowers, these plants, and these fruits which He causes the earth to bring forth for our comfort and advantage.

- Speech to the Hawarden Amateur Horticultural Society (17 August 1876), as quoted in "Mr. Gladstone On Cottage Gardening", The Times (18 August 1876), p. 9

- Let the Turks now carry away their abuses, in the only possible manner, namely, by carrying off themselves. Their Zaptiehs and their Mudirs, their Bimbashis and Yuzbashis, their Kaimakams and their Pashas, one and all, bag and baggage, shall, I hope, clear out from the province that they have desolated and profaned. This thorough riddance, this most blessed deliverance, is the only reparation we can make to those heaps and heaps of dead, the violated purity alike of matron and of maiden and of child; to the civilization which has been affronted and shamed; to the laws of God, or, if you like, of Allah; to the moral sense of mankind at large. There is not a criminal in a European jail, there is not a criminal in the South Sea Islands, whose indignation would not rise and over-boil at the recital of that which has been done, which has too late been examined, but which remains unavenged, which has left behind all the foul and all the fierce passions which produced it and which may again spring up in another murderous harvest from the soil soaked and reeking with blood and in the air tainted with every imaginable deed of crime and shame. That such things should be done once is a damning disgrace to the portion of our race which did them; that the door should be left open to their ever so barely possible repetition would spread that shame over the world!

- Let me endeavour, very briefly to sketch, in the rudest outline what the Turkish race was and what it is. It is not a question of Mohammedanism simply, but of Mohammedanism compounded with the peculiar character of a race. They are not the mild Mohammedans of India, nor the chivalrous Saladins of Syria, nor the cultured Moors of Spain. They were, upon the whole, from the black day when they first entered Europe, the one great anti-human specimen of humanity. Wherever they went a broad line of blood marked the track behind them, and, as far as their dominion reached, civilization vanished from view. They represented everywhere government by force as opposed to government by law. – Yet a government by force can not be maintained without the aid of an intellectual element. – Hence there grew up, what has been rare in the history of the world, a kind of tolerance in the midst of cruelty, tyranny and rapine. Much of Christian life was contemptuously left alone and a race of Greeks was attracted to Constantinople which has all along made up, in some degree, the deficiencies of Turkish Islam in the element of mind!

- Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East. (1876)[1]

- As the British Constitution is the most subtile organism which has proceeded from the womb and the long gestation of progressive history, so the American Constitution is, so far as I can see, the most wonderful work ever struck off by the brain and purpose of man.

- Kin Beyond Sea, published in The North American Review, pp. 179-202

- It is [America] alone who, at a coming time, can, and probably will, wrest from us that commercial primacy. We have no title, I have no inclination, to murmur at the prospect...We have no more title against her than Venice, or Genoa, or Holland, has had against us.

- 'Kin beyond Sea', The North American Review Vol. 127, No. 264 (Sep. - Oct., 1878), p. 180.

- National injustice is the surest road to national downfall.

- Speech, Plumstead (30 November 1878)

- The disease of an evil conscience is beyond the practice of all the physicians of all the countries in the world.

- Speech, Plumstead (30 November 1878)

- I think that the principle of the Conservative Party is jealousy of liberty and of the people, only qualified by fear; but I think the principle of the Liberal Party is trust in the people, only qualified by prudence.

- Speech at the opening of the Palmerston Club, Oxford (December 1878) as quoted in "Gladstone's Conundrums; The Statesman Answers Sundry Interesting Questions" in The New York Times (9 February 1879)

- A rational reaction against the irrational excesses and vagaries of scepticism may, I admit, readily degenerate into the rival folly of credulity. To be engaged in opposing wrong affords, under the conditions of our mental constitution, but a slender guarantee for being right.

- Homeric Synchronism : An Enquiry Into the Time and Place of Homer (1876), Introduction

- ...the great duty of a Government, especially in foreign affairs, is to soothe and tranquillize the minds of the people, not to set up false phantoms of glory which are to delude them into calamity, not to flatter their infirmities by leading them to believe that they are better than the rest of the world, and so to encourage the baleful spirit of domination; but to proceed upon a principle that recognises the sisterhood and equality of nations, the absolute equality of public right among them; above all, to endeavour to produce and to maintain a temper so calm and so deliberate in the public opinion of the country, that none shall be able to disturb it.

- Speech in Edinburgh (25 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 37.

- I wish to dissipate, if I can, the idle dreams of those who are always telling you that the strength of England depends, sometimes they say upon its prestige, sometimes they say upon its extending its Empire, or upon what it possesses beyond the seas. Rely upon it the strength of Great Britain and Ireland is within the United Kingdom.

- Speech in Edinburgh (25 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 46.

- Remember the rights of the savage, as we call him. Remember that the happiness of his humble home, remember that the sanctity of life in the hill villages of Afghanistan among the winter snows, are as sacred in the eye of Almighty God as are your own. Remember that He who has united you together as human beings in the same flesh and blood, has bound you by the law of mutual love, that that mutual love is not limited by the shores of this island, is not limited by the boundaries of Christian civilisation, that it passes over the whole surface of the earth, and embraces the meanest along with the greatest in its wide scope.

- Speech, Foresters' Hall, Dalkeith, Scotland (26 November 1879) as part of the Midlothian campaign; published in "Mr Gladstone's visit to Mid-Lothian: Meeting at the Foresters' Hall" (27 November 1879), The Scotsman, p. 6; also quoted in Life of Gladstone (1903) by John Morley, II, (p. 595)

- Here is my first principle of foreign policy: good government at home. My second principle of foreign policy is this—that its aim ought to be to preserve to the nations of the world—and especially, were it but for shame, when we recollect the sacred name we bear as Christians, especially to the Christian nations of the world—the blessings of peace. That is my second principle.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 115.

- In my opinion the third sound principle is this—to strive to cultivate and maintain, ay, to the very uttermost, what is called the concert of Europe; to keep the Powers of Europe in union together. And why? Because by keeping all in union together you neutralize and fetter and bind up the selfish aims of each. I am not here to flatter either England or any of them. They have selfish aims, as, unfortunately, we in late years have too sadly shown that we too have had selfish aims; but then common action is fatal to selfish aims. Common action means common objects; and the only objects for which you can unite together the Powers of Europe are objects connected with the common good of them all. That, gentlemen, is my third principle of foreign policy.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), pp. 115-116.

- My fourth principle is—that you should avoid needless and entangling engagements. You may boast about them, you may brag about them, you may say you are procuring consideration of the country. You may say that an Englishman may now hold up his head among the nations. But what does all this come to, gentlemen? It comes to this, that you are increasing your engagements without increasing your strength; and if you increase your engagements without increasing strength, you diminish strength, you abolish strength; you really reduce the empire and do not increase it. You render it less capable of performing its duties; you render it an inheritance less precious to hand on to future generations.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 116.

- My fifth principle is...to acknowledge the equal rights of all nations. You may sympathize with one nation more than another. Nay, you must sympathize in certain circumstances with one nation more than another. You sympathize most with those nations, as a rule, with which you have the closest connection in language, in blood, and in religion, or whose circumstances at the time seem to give the strongest claim to sympathy. But in point of right all are equal, and you have no right to set up a system under which one of them is to be placed under moral suspicion or espionage, or to be made the constant subject of invective. If you do that, but especially if you claim for yourself a superiority, a pharisaical superiority over the whole of them, then I say you may talk about your patriotism if you please, but you are a misjudging friend of your country, and in undermining the basis of the esteem and respect of other people for your country you are in reality inflicting the severest injury upon it.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), pp. 116-117.

- [My sixth principle is that] the foreign policy of England should always be inspired by the love of freedom. There should be a sympathy with freedom, a desire to give it scope, founded not upon visionary ideas, but upon the long experience of many generations within the shores of this happy isle, that in freedom you lay the firmest foundations both of loyalty and order; the firmest foundations for the development of individual character; and the best provision for the happiness of the nation at large.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 117.

- Of all the principles, gentlemen, of foreign policy which I attach the greatest value is the principle of the equality of nations; because, without recognising that principle, there is no such thing as public right, and without public international right there is no instrument available for settling the transactions of mankind except material force. Consequently, the principle of equality among nations lies, in my opinion, at the very basis and root of a Christian civilisation, and when that principle is compromised or abandoned, with it must depart our hopes of tranquillity and of progress for mankind.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 123.

- What did the two words "Liberty and Empire" mean in the Roman mouth? They meant simply this: liberty for ourselves, empire over the rest of mankind.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in The Times (28 November 1878), p. 10. The Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli had proclaimed his policy as "Imperium et Libertas".

- The Chancellor of the Exchequer should boldly uphold economy in detail; and it is the mark of a chicken-hearted Chancellor when he shrinks from upholding economy in detail, when because it is a question of only two or three thousand pounds, he says it is no matter. He is ridiculed, no doubt, for what is called candle-ends and cheese-parings, but he is not worth his salt if he is not ready to save what are meant by candle-ends and cheese-parings in the cause of the country. No Chancellor of the Exchequer is worth his salt who makes his own popularity either his consideration, or any consideration at all, in administering the public purse. In my opinion, the Chancellor of the Exchequer is the trusted and confidential steward of the public. He is under a sacred obligation with regard to all that he consents to spend.

- Speech in Edinburgh (29 November 1879), quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 243

- ...that Chancellor of the Exchequer is the very man who comes down to corrupt whatever there is of financial virtue in us, and to instil into our minds those seductive and poisonous ideas that it does not, after all, matter very much if there is a deficit, and that it is extremely disagreeable when commerce is not in the most flourishing state to call upon the people to pay. Was that the practice of Sir Robert Peel? ... he came to Parliament and stood at his place in the House of Commons, pointed out the figures as they stood, and said to them—I ask you, will you resort to the "miserable expedient" of tolerating deficit, and of making provision by loans from year to year? That which he denounced as the "miserable expedient" has become the standing law, has become almost the financial gospel of the Government that is now in power.

- Speech in Edinburgh (29 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 152.

1880s

- We must fall back upon the broad, the incorruptible power of national liberty; that we decline to recognise any class whatever, be they peers or be they gentry, be they what you like, as entitled to direct the destinies of this nation against the will of the nation.

- Speech at Pathhead, Scotland (23 March 1880), quoted in Political Speeches in Scotland, March and April 1880 (Edinburgh: Andrew Elliot, 1880), p. 268.

- As he lived, so he died — all display, without reality or genuineness.

- Of Benjamin Disraeli, in May 1881 to his secretary, Edward Hamilton, regarding Disraeli's instructions to be given a modest funeral. Disraeli was buried in his wife's rural churchyard grave. Gladstone, Prime Minister at the time, had offered a state funeral and a burial in Westminster Abbey. Quoted in chapter 11 of Gladstone: A Biography (1954) by Philip Magnus

- The reason why the foreign producer gets his produce to market cheaper, relatively, is this — that foreign produce is collected and brought in such large quantities and is sent in great masses to the market. That is the secret of cheap carriage... We must try to make our pounds of produce into tons — or must bring together a number of producers. If you small agriculturists can collectively offer a great bulk of merchandise to the railway companies, they will give you good terms.

- Speech at Hawarden (5 January 1884), quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 258

- Ideal perfection is not the true basis of English legislation. We look at the attainable; we look at the practicable; and we have too much of English sense to be drawn away by those sanguine delineations of what might possibly be attained in Utopia, from a path which promises to enable us to effect great good for the people of England.

- Speech in the House of Commons (28 February 1884) during a debate on the Representation of the People Bill.

- The right hon. Gentleman quoted repeatedly this declaration...to keep [rebellion] out of Egypt it is necessary to put it down in the Soudan; and that is the task the right hon. Gentleman desires to saddle upon England. Now, I tell hon. Gentlemen this—that that task means the reconquest of the Soudan. I put aside for the moment all questions of climate, of distance, of difficulties, of the enormous charges, and all the frightful loss of life. There is something worse than that involved in the plan of the right hon. Gentleman. It would be a war of conquest against a people struggling to be free. ["No, no!"] Yes; these are people struggling to be free, and they are struggling rightly to be free.

- Speech in the House of Commons (12 May 1884) during the Mahdist War.

- There is a process of slow modification and development mainly in directions which I view with misgiving. "Tory democracy," the favourite idea on that side, is no more like the Conservative party in which I was bred, than it is like Liberalism. In fact less. It is demagogism … applied in the worst way, to put down the pacific, law-respecting, economic elements which ennobled the old Conservatism, living upon the fomentation of angry passions, and still in secret as obstinately attached as ever to the evil principle of class interests. The Liberalism of to-day is better … yet far from being good. Its pet idea is what they called construction, — that is to say, taking into the hands of the State the business of the individual man. Both the one and the other have much to estrange me, and have had for many, many years.

- Letter to Lord Acton (11 February 1885), quoted in The Life of William Ewart Gladstone Volume III (1903) by John Morley, p. 172

- [An] Established Clergy will always be a tory Corps d'Armée.

- Letter to Sir William Harcourt (3 July 1885), quoted in H. C. G. Matthew (ed.), The Gladstone Diaries: Volume 10: January 1881-June 1883 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), p. clxix.

- The rule of our policy is that nothing should be done by the state which can be better or as well done by voluntary effort; and I am not aware that, either in its moral or even its literary aspects, the work of the state for education has as yet proved its superiority to the work of the religious bodies or of philanthropic individuals. Even the economical considerations of materially augmented cost do not appear to be wholly trivial.

- Socialism. Here I am at one with you. I have always been opposed to it. It is now taking hold of both parties, in a way I much dislike: & unhappily Lord Salisbury is one of its leaders, with no Lord Hartington (see his speech at Darwen) to oppose him.

- Letter to Lord Southesk (27 October 1885)

- I would tell them of my own intention to keep my counsel...and I will venture to recommend them, as an old Parliamentary hand, to do the same.

- Speech in the House of Commons (21 January 1886).

- On the side adverse to the Government are found...in profuse abundance, station, title, wealth, social influence, the professions, or the large majority of them—in a word, the spirit and power of class. These are the main body of the opposing host. Nor is that all. As knights of old had squires, so in the great army of class each enrolled soldier has, as a rule, dependents. The adverse host, then, consists of class and the dependents of class. But this formidable army is in the bulk of its constituent parts the same...that has fought in every one of the great political battles of the last 60 years, and has been defeated. We have had great controversies before this great controversy—on free trade, free navigation, public education, religious equality in civil matters, extension of the suffrage to its present basis. On these and many other great issues the classes have fought uniformly on the wrong side, and have uniformly been beaten by a power more difficult to marshal, but resistless when marshalled—by the upright sense of the nation.

- Address to the electors of Midlothian, Daily Review (3 May 1886), quoted in The Times (4 May 1886), p. 5.

- The difference between giving with freedom and dignity on the one side, with acknowledgment and gratitude on the other, and giving under compulsion—giving with disgrace, giving with resentment dogging you at every step of your path—this difference is, in our eyes, fundamental, and this is the main reason not only why we have acted, but why we have acted now. This, if I understand it, is one of the golden moments of our history—one of those opportunities which may come and may go, but which rarely return, or, if they return, return at long intervals, and under circumstances which no man can forecast.

- Speech in the House of Commons (7 June 1886) introducing the Home Rule Bill

- Ireland stands at your bar expectant, hopeful, almost suppliant. Her words are the words of truth and soberness. She asks a blessed oblivion of the past, and in that oblivion our interest is deeper than even hers. ...She asks also a boon for the future; and that boon for the future, unless we are much mistaken, will be a boon to us in respect of honour, no less than a boon to her in respect of happiness, prosperity, and peace. Such, Sir, is her prayer. Think, I beseech you, think well, think wisely, think, not for the moment, but for the years that are to come, before you reject this Bill.

- Speech in the House of Commons (7 June 1886) introducing the Home Rule Bill

- This I must tell you, if we are compelled to go into it—your position against us, the resolute banding of the great, and the rich, and the noble, and I know not who against the true genuine sense of the people compels us to unveil the truth; and I tell you this—that, so far as I can judge, and so far as my knowledge goes, I grieve to say in the presence of distinguished Irishmen that I know of no blacker or fouler transaction in the history of man than the making of the Union.

- Speech in Liverpool (28 June 1886), quoted in The Times (29 June 1886), p. 11.

- I will venture to say that upon the one great class of subjects, the largest and the most weighty of them all, where the leading and determining considerations that ought to lead to a conclusion are truth, justice and humanity—upon these, gentlemen, all the world over, I will back the masses against the classes.

- Speech in Liverpool (28 June 1886), quoted in The Times (29 June 1886), p. 11.

- What is a public meeting? It is not an anarchical combination—it is not a mob—it is an assemblage of rational beings to which, if the invitation be general, every man has a right to go, and the Government reporter has a right to go, but only like others and subject to the ordinary law. But if instead of appealing to the promoters of the meeting...to afford the Government reporter facilities, if instead of that the method of violence is resorted to, then I say the law was broken by the agents of the law. It is idle to speak to the Irish people of the duty of obeying the law, or to bring in Coercion Bills to make them obey the law, if the very Government that so speaks and that brings in these Bills has agents who violate the law by violently breaking up orderly public meetings, and who are sustained by the Ministers of the Crown in this illegal action.

- Speech in Nottingham (18 October 1887) referring to the Mitchelstown Massacre, quoted in The Times (19 October 1887), p. 6.

- I have said, and I say again, "Remember Mitchelstown".

- Speech in Nottingham (18 October 1887), quoted in The Times (19 October 1887), p. 6.

- The coercion which has been introduced has not been a coercion against crime...It has been a coercion against combination. And combination—it stands and glares upon us from every page in the history of Ireland—is the only arm by which a poor and destitute and feeble population are able to make good their ground, even in the slightest degree, against the domineering power of the State and of the wealthy with England at their back.

- Speech in London (9 May 1888), quoted in The Times (10 May 1888), p. 8.

- This Coercion Act professes to be in the main an Act directed against conspiracy, and conspiracy is a bad thing. But under the name of conspiracy we say that it is directed against combination. Combination is not always a very good thing, but combination is very often the sole means by which the weak can protect themselves against the strong, the poor against the wealthy.

- Speech in London (30 June 1888), quoted in The Times (2 July 1888), p. 7.

- Think, ladies and gentlemen, of your "Men of Harlech". In my judgment, for the purpose of a national air...and without disparagement of old "God save the Queen" or anything else, it is perhaps the finest national air in the world.

- Speech to the Eisteddfod in Wrexham (8 September 1888), quoted in A. W. Hutton and H. J. Cohen (eds.), The Speeches of The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone on Home Rule, Criminal Law, Welsh and Irish Nationality, National Debt and the Queen's Reign. 1888–1891 (London: Methuen, 1902), p. 56.

- ...the principle of nationality and the principle of reverence for antiquity—the principle of what I may call local patriotism—is not only an ennobling thing in itself, but has a great economic value. ... The attachment to your country, the attachment among British subjects to Britain, but also the attachment among Welsh-born people to Wales, has in it, in some degrees, the nature both of an appeal to energy and an incentive to its development, and likewise, no few elements of a moral standard; for the Welshman, go where he may, will be unwilling to disgrace the name. It is a matter of familiar observation that even in the extremest east of Europe, wherever free institutions have supplanted a state of despotic government, the invariable effect has been to administer an enormous stimulus to the industrious activity of the country.

- Speech to the Eisteddfod in Wrexham (8 September 1888), quoted in A. W. Hutton and H. J. Cohen (eds.), The Speeches of The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone on Home Rule, Criminal Law, Welsh and Irish Nationality, National Debt and the Queen's Reign. 1888–1891 (London: Methuen, 1902), p. 58.

- The Welsh made a very good and a very hard fight against the English in self-defence, and what was the consequence? That the English were obliged to surround your territory with great castles; and the effect of this has been that, as far as I can reckon, more by far than one-half of the great remains of the castles in the whole island south of the Tweed are castles that surround Wales. That shows that Wales was inhabited by men, and by men who valued and were disposed to struggle for their liberties.

- Speech to the Eisteddfod in Wrexham (8 September 1888), quoted in A. W. Hutton and H. J. Cohen (eds.), The Speeches of The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone on Home Rule, Criminal Law, Welsh and Irish Nationality, National Debt and the Queen's Reign. 1888–1891 (London: Methuen, 1902), p. 61.

- The peculiarity of this strike...has been that a great number of separate trades, which have nothing to do with one another...have shown that they intend to make common cause. You may depend upon it that this is a social fact of the highest importance and of very general importance of the future. I believe that the lesson has been learnt from Ireland, and that it is due to the present Government and to its coercive laws in Ireland, and to the necessity which they have laid upon the people of Ireland in different parts of the country which have no connexion with one another to associate together for an object which they believe to be vital to all. I am much inclined to think that the working men of London have learnt this lesson from Ireland.

- Speech in Cheshire (23 September 1889) on the London dock strike, quoted in The Times (24 September 1889), p. 10.

- An enlightened impartial observer...will be disposed to think that in the common interests of humanity this remarkable strike and the results of this strike, which have tended somewhat to strengthen the condition of labour in the face of capital, is the record of what we ought to regard as satisfactory, as a real social advance; that it tends to a greater, a more uniform, and a more firm establishment of just relations; that it tends to a fair principle of division of the fruits of industry.

- Speech in Cheshire (23 September 1889) on the London dock strike, quoted in The Times (24 September 1889), p. 10.

- But let the working man be on his guard against another danger. We live at a time when there is a disposition to think that the Government ought to do this and that and that the Government ought to do everything. There are things which the Government ought to do, I have no doubt. In former periods the Government have neglected much, and possibly even now they neglect something; but there is a danger on the other side. If the Government takes into its hands that which the man ought to do for himself it will inflict upon him greater mischiefs than all the benefits he will have received or all the advantages that would accrue from them. The essence of the whole thing is that the spirit of self-reliance, the spirit of true and genuine manly independence, should be preserved in the minds of the people, in the minds of the masses of the people, in the mind of every member of the class. If he loses his self-denial, if he learns to live in a craven dependence upon wealthier people rather than upon himself, you may depend upon it he incurs mischief for which no compensation can be made.

- Speech at the opening of the Reading and Recreation Rooms erected by the Saltney Literary Institute at Saltney in Chesire (26 October 1889), as quoted in "Mr. Gladstone On The Working Classes" in The Times (28 October 1889), p. 8

1890s

- All selfishness is the great curse of the human race, and when we have a real sympathy with other people less happy than ourselves that is a good sign of something like a beginning of deliverance from selfishness.

- Speech at Hawarden (28 May 1890), quoted in The Times (29 May 1890), p. 12.

- ...the practice of thrift is not one of the most distinguishing characteristics of the people of this country. It exists more beyond the border, in Scotland, undoubtedly, than it does in England, but it is increasing, and increasing very much, happily, in England itself. I rejoice to say that it has been in the power of the State to effect this by judicious legislation—not by what is called "grandmotherly legislation", of which I for one have a great deal of suspicion—but by legislation thoroughly sound in principle—namely, that legislation which like your savings bank, helps the people by enabling the people to help themselves.

- Speech to the annual meeting of the depositors in the provident savings banks connected with the South-Eastern and Metropolitan Railway Companies in the City Terminus Hotel (18 June 1890), quoted in The Times (19 June 1890), p. 6.

- ...the finances of the country is intimately associated with the liberties of the country. It is a powerful leverage by which English liberty has been gradually acquired. Running back into the depths of antiquities for many centuries, it lies at the root of English liberty, and if the House of Commons can by any possibility lose the power of the control of the grants of public money, depend upon it your very liberty will be worth very little in comparison.

- Speech in Hastings (17 March 1891), quoted in A. W. Hutton and H. J. Cohen (eds.), The Speeches of The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone on Home Rule, Criminal Law, Welsh and Irish Nationality, National Debt and the Queen's Reign. 1888–1891 (London: Methuen, 1902), p. 343.

- I name next a word that it requires some courage to utter these days—the word of economy. It is like a echo from the distant period of my early life. The wealth of the country, and the vast comparative diffusion of comfort, has, I am afraid, put public economy, at least in its more rigid and severe forms, sadly out of countenance.

- Speech in Newcastle (2 October 1891), quoted in A. W. Hutton and H. J. Cohen (eds.), The Speeches of The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone on Home Rule, Criminal Law, Welsh and Irish Nationality, National Debt and the Queen's Reign. 1888–1891 (London: Methuen, 1902), p. 377.

- There ought to be a great effort of the Liberal party to extend the labour representation in Parliament. .... And we affirm that it is among the high and indispensable duties of the party...to proceed to provide for the establishment of district councils and parish councils, and thereby to bring self-government to the very doors of the labouring men throughout the country. Further, I will add boldly that it will be their duty to enact compulsory powers for the purpose of enabling suitable bodies to acquire land upon fair and suitable terms, in order to place the rural population in nearer relations to the land, to the use and profit of the land which they have so long tilled for the benefit of others, but for themselves almost in vain.

- Speech in Newcastle (2 October 1891), quoted in A. W. Hutton and H. J. Cohen (eds.), The Speeches of The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone on Home Rule, Criminal Law, Welsh and Irish Nationality, National Debt and the Queen's Reign. 1888–1891 (London: Methuen, 1902), pp. 383-384, 386.

- That reform of the land laws, that abolition of the present system of entail, together with just facilities for the transfer of land, is absolutely necessary in order to do anything like common justice to those who inhabit the rural parts of this country, and whom, instead of seeing them, as we now see them, dwindle from one census to another, I, for my part, and I believe you, along with me, would heartily desire to see maintained, not in their present number only, but in increasing numbers over the whole surface of the land.

- Speech in Newcastle (2 October 1891), quoted in A. W. Hutton and H. J. Cohen (eds.), The Speeches of The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone on Home Rule, Criminal Law, Welsh and Irish Nationality, National Debt and the Queen's Reign. 1888–1891 (London: Methuen, 1902), p. 386.

- It is a lamentable fact if, in the midst of our civilization, and at the close of the nineteenth century, the workhouse is all that can be offered to the industrious labourer at the end of a long and honourable life. I do not enter into the question now in detail. I do not say it is an easy one; I do not say that it will be solved in a moment; but I do say this, that until society is able to offer to the industrious labourer at the end of a long and blameless life something better than the workhouse, society will not have discharged its duties to its poorer members.

- Speech in London (11 December 1891), quoted in The Times (12 December 1891), p. 7.

- There is a saying of Burke's from which I must utterly dissent. "Property is sluggish and inert." Quite the contrary. Property is vigilant, active, sleepless; if ever it seems to slumber, be sure that one eye is open.

- Remarks to John Morley (31 December 1891), quoted in John Morley, The Life of William Ewart Gladstone. Vol. III (1880-1898) (Macmillan, 1903), p. 469

- Protectionism and militarism are united in an unholy but yet a valid marriage: and the one and the other are in my firm conviction alike the foes of freedom.

- Letter to the Marchese di Rudinì (30 April 1892), quoted in Vilfedo Pareto, Liberté économique et les événements d'Italie (1970), p. 49

- You are told that education, that enlightenment, that leisure, that high station, that political experience are arrayed in the opposing camp, and I am sorry to say that to a large extent I cannot deny it. But though I cannot deny it, I painfully reflect that in almost every one, if not in every one, of the great political controversies of the last 50 years, whether they affected the franchise, whether they affected commerce, whether they affected religion, whether they affected the bad and abominable institution of slavery, or whatever subject they touched, these leisured classes, these educated classes, these wealthy classes, these titled classes, have been in the wrong.

- Speech in Edinburgh (30 June 1892), quoted in The Times (1 July 1892), p. 12.

- Let us go forward in the good work we have in hand and let us put our trust, not in squires and peers, and not in titles or in acres; I will go further and say, not in man, as such, but in Almighty God, who is the God of justice, and who has ordained the principle of right, of equity, and of freedom to be the guides and the masters of our lives.

- Speech in Edinburgh (30 June 1892), quoted in The Times (1 July 1892), p. 12.

- [I was] a youth in his twenty third year, young of his age, who had seen little or nothing of the world, who resigned himself to politics, but whose desire had been for the ministry of God. The remains of this desire operated unfortunately. They made me tend to glorify in an extravagant manner and degree not only the religious character of the State, which in reality stood low, but also the religious mission of the Conservative party. There was, to my eyes, a certain element of AntiChrist in the Reform Act and that Act was cordially hated. ... It was only under the (second) Government of Sir Robert Peel that I learned how impotent [and] barren was the conservative office for the Church.

- 'My Earlier Political Opinions. (II) The Extrication' (16 July 1892), quoted in John Brooke and Mary Sorensen (eds.), The Prime Minister's Papers: W. E. Gladstone. I: Autobiographica (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1971), p. 40.

- I cannot help regretting that the hon. and gallant Gentleman has felt it his duty to put the question. It is put under circumstances that naturally belong to one of those fluctuations in the condition of trade which, however unfortunate and lamentable they may be, recur from time to time. Undoubtedly I think that questions of this kind, whatever be the intention of the questioner, have a tendency to produce in the minds of people, or to suggest to the people, that these fluctuations can be corrected by the action of the Executive Government. Anything that contributes to such an impression inflicts an injury upon the labouring population.

- Speech in the House of Commons (1 September 1893) in answer to a question from Howard Vincent MP who asked Gladstone "if the Government propose to take any steps to mitigate the consequences to the masses of the people" of unemployment.

- I am thankful to have borne a part in the emancipating labours of the last sixty years; but entirely uncertain how, had I now to begin my life, I could face the very different problems of the next sixty years. Of one thing I am, and always have been, convinced—it is not by the State that man can be regenerated, and the terrible woes of this darkened world effectually dealt with. In some, and some very important, respects, I yearn for the impossible revival of the men and the ideas of my first twenty years, which immediately followed the first Reform Act.

- Letter to George William Erskine Russell (6 March 1894), quoted in G. W. E. Russell, One Look Back (Wells Gardner, Darton and Co., 1911), p. 265.

- This means war!

- Remark upon seeing the German fleet at the opening of the Kiel Canal (20 June 1895), quoted in H. C. G. Matthew, Gladstone, 1875–1898 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), p. 352, n.

- To serve Armenia is to serve the Civilization.

- A letter from 1 May, 1896, Hawarden, as cited in: Mesrovb Jacob Seth (1937). Armenians in India, from the Earliest Times to the Present Day: A Work of Original Research. Asian Educational Services. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-81-206-0812-2.

- 'Great Assassin'

- In a speech in Liverpool on September 24, 1896, Gladstone gave this title to sultan Abdul Hamid II of Turkey, organizer of the Armenian genocide.[2]

- I am fundamentally a dead man: one fundamentally a Peel–Cobden man.

- Letter to James Bryce (5 December 1896), quoted in Andrew Marrison (ed.), Free Trade and its Reception 1815-1960: Freedom and Trade: Volume One (London: Routledge, 2002), p. 209.

- I venture on assuring you that I regard the design formed by you and your friends with sincere interest, and in particular wish well to all the efforts you may make on behalf of individual freedom and independence as opposed to what is termed Collectivism.

- Letter to F. W. Hirst on being unable to write a preface to Essays in Liberalism by "Six Oxford Men" (2 January 1897), as quoted In the Golden Days (1947) by F. W. Hirst, p. 158

- The hopelessness of the Turkish Government should make me witness with delight its being swept out of the countries which it tortures. Next to the Ottoman Government nothing can be more deplorable and blameworthy than jealousies between Greek and Slav and plans by the States already existing for appropriating other territory. Why not Macedonia for the Macedonians as well as Bulgaria for the Bulgarians and Serbia for the Serbians?

- Letter quoted in Mr. Gladstone and The Balkan Confederation in The Times (6 February 1897)

- In 1834 the Government...did themselves high honour by the new Poor Law Act, which rescued the English peasantry from the total loss of their independence.

- 'Early Parliamentary Life 1832–52. 1833–4 in the old House of Commons' (3 June 1897), quoted in John Brooke and Mary Sorensen (eds.), The Prime Minister's Papers: W. E. Gladstone. I: Autobiographica (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1971), p. 55.

Disputed

- Holding up a Qur'an in the House of Commons; quoted in Rafiq Zakaria, Muhammad and the Quran (Penguin Books, 1991), p. 59.

- Variant: "As long as a copy of this accursed book survives there can be no justice in the world." Quoted in Paul G. Lauren, ed., The China Hands' Legacy: Ethics and Diplomacy (Westview Press, 1987), p. 136.

- «Gladstone...threw the Quran into a closet and said, 'There will be no quiet in the world as long as this remains.'» Reported in Army Officers in Arab Politics and Society (1970) by Eliezer Bee̓ri, p. 367.

- Holding up a Qur'an in the House of Commons; quoted in Rafiq Zakaria, Muhammad and the Quran (Penguin Books, 1991), p. 59.

This quote was fabricated in a German document of 1915 "Kriegsurkunden. 17. Fatwa des Scheich es-Saijid Hibet ed-Din esch-Schahrastani en-Nedschefi über die Freundschaft der Muslime mit den Deutschen", at a time when the Germans were attempting to persuade the Arabic nations to side with them rather than the British. The 'quote' was 'discovered' in the 1950s and widely repeated by the Muslim Brotherhood and Egyptian press as part of a campaign to remove British influence from Egypt. There are no credible contemporary records and Hansard contains no record of the statement.

- Show me the manner in which a nation or a community cares for its dead. I will measure exactly the sympathies of its people, their respect for the laws of the land, and their loyalty to high ideals.

- Attributed in "Successful Cemetery Advertising" in The American Cemetery (March 1938), p. 13; reported as unverified in Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations (1989)

- We look forward to the time when the Power of Love will replace the Love of Power. Then will our world know the blessings of peace.

- Attributed in The National elementary principal (1948) - Volume 28 - Page 34; a similar statement has also become attributed to Jimi Hendrix: "When the power of love overcomes love of power the world will know peace." A similar quotation is found in My Heart Shall Give A Oneness-Feast (1993) by Sri Chinmoy: "My books, they all have only one message: the heart's Power Of Love must replace the mind's Love Of Power. If I have the Power Of Love, then I shall claim the whole World as my own … World Peace can be achieved when the Power Of Love replaces the Love Of Power." An even earlier statement of Chinmoy is found in Meditations: Food For The Soul (1970): "When the power of love replaces the love of power, man will have a new name: God."

Misattributed

- Nothing, that is morally wrong, can be politically right.

- No citation to Gladstone found. Hannah More in 1837 in Hints Towards Forming the Character of a Young Princess, The Works of Hannah More, Vol. 4, said the following on p. 179: "On the Whole, we need not hesitate to assert, that in the long course of events, nothing, that is morally wrong, can be politically right. Nothing, that is inequitable, can be finally successful."

- The best way to see London is from the top of a bus.

- No known direct citation to Gladstone; first attributed in early 1900s (e.g. Highways and byways in London, 1903, Emily Constance Baird Cook, Macmillan and Co.) but appears in late 1800s London guides by other authors, such as:

- The best way to see London is by the omnibus lines.

- A Tour Around the World in 1884: or Sketches of Travel in the Eastern and Western Hemispheres (1886) by John B. Gorman

- The best way to see London is by the omnibus lines.

- [Money should] fructify in the pockets of the people.

- Often attributed to Gladstone. During the debate on the budget of 1867, Laing quoted Lord Sydenham's use of the phrase in 1832 to Gladstone, with Gladstone replying: "...when you talk of the "fructification" of money — I accept the term, which is originally due to very high authority — for the public advantage, there is none much more direct and more complete than that which the public derives from money applied to the reduction of debt." The phrase itself occurs earlier, among others:

- ...ought we to appropriate in the present circumstances of the country 3 millions of money out of the resources and productive capital of the nation, to create an addition to the treasury of the state? Ought we to reduce our public debt by a sacrifice of the funds that maintained national industry? Ought we to deprive the people of 3 millions of capital, which would fructify in their hands much more than in those of government, to pay a portion of our debt?

- He put it to his hon. friend the member for Taunton, whether for the sake of increasing the fictitious value of stock, the grinding taxation which encroached on the capital that formed the foundation of credit, ought to be endured? He put it to his powerful mind, whether it would not be better to leave in the pockets of the people what increased and fructified with them, than, by taking all away, to ruin them and annihilate the revenue?

- The right hon. gentleman had urged, as one 331 objection to the application of the surplus of five millions as a sinking fund, that it was taking that sum from the people, which would fructify to the national advantage, in their pockets, much more than in the reduction of the debt.

- It was one of the great errors of Mr. Pitt's system, that the people should be taxed to buy up a debt standing at four or five per cent interest, when it was clear that that money, if left to fructify in the pockets of the people, would be productive of infinitely more benefit to the country.

Quotes about Gladstone

- If there were no Tories, I am afraid he would invent them.

- Lord Acton, in a letter to Mrs. Drew (24 April 1881)

- Mr. Gladstone once said to me: “If you ever have to form a Government, you must steel your nerves, and act the butcher”: a piece of very sound advice (as I learned from experience).

- H. H. Asquith, Studies and Sketches (1924), pp. 205–206

- He has — and it is one of the springs of great power — a real faith in the higher parts of human nature; he believes, with all his heart and soul and strength, that there is such a thing as truth; he has the soul of a martyr with the intellect of an advocate.

- Walter Bagehot, in "Mr. Gladstone," National Review (July 1860)

- Who equals him in earnestness? Who equals him in eloquence? Who equals him in courage and fidelity to his convictions? If these gentlemen who say they will not follow him have anyone who is equal, let them show him. If they can point out any statesman who can add dignity and grandeur to the stature of Mr. Gladstone, let them produce him!

- John Bright, speech at Birmingham, (22 April 1867)

- An almost spectral kind of phantasm of a man — nothing in him but forms and ceremonies and outside wrappings.

- Thomas Carlyle, letter (March 1873)

- They told me how Mr. Gladstone read Homer for fun, which I thought served him right.

- Winston Churchill (Attributed)

- What you say about Gladstone is most just. What restlessness! What vanity! And what unhappiness must be his! Easy to say he is mad. It looks like it. My theory about him is unchanged: A ceaseless Tartuffe from the beginning. That sort of man does not get mad at 70.

- Benjamin Disraeli, letter to Lady Bradford (3 October 1879)

- I saw in the face of Mr. Gladstone a blending of opposite qualities. There were the peace and gentleness of the lamb, with the strength and determination of the lion. Deep earnestness was expressed in all his features. He began his speech in a tone conciliatory and persuasive. His argument against the bill was based upon statistics which he handled with marvelous facility. He showed that the number of crimes in Ireland for which the Force Bill was claimed as a remedy by the Government was not greater than the great class of crimes in England, and that therefore there was no reason for a Force Bill in one country more than in the other. After marshaling his facts and figures to this point, in a masterly and convincing manner, raising his voice and pointing his finger directly at Mr. Balfour, he exclaimed, in a tone almost menacing and tragic, "What are you fighting for?" The effect was thrilling. His peroration was a splendid appeal to English love of liberty. When he sat down the House was instantly thinned out. There seemed neither in members nor spectators any desire to hear another voice after hearing Mr. Gladstone's.

- Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892), Part Three, Ch. 8: "European Tour"

- At dinner we talked of Newman, whose Dream of Gerontius Gladstone puts very high, so high that he speaks of it in the same breath with the Divina Commedia. At length he asked, "Which of his writings will be read in a hundred years?" "Well," said Henry Smith, "certainly his hymn, 'Lead kindly Light,' and 'The Parting of Friends,' the sermon he preached before leaving Littlemore." "I go further," said Gladstone. "I think all his parochial sermons will be read."

- Sir Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant Duff, in Notes from a Diary, 1851-1901: 1873-1881 (1898), p. 140

- To myself, and to many thousands, the assumption by Mr. Gladstone of the leadership of the Liberal party in the House of Commons seemed to promise the inauguration of a new era. It was known that he was as favourable to the revision and enlargement of the representation of the people in Parliament as Palmerston had been opposed to such changes, and the working classes hailed his accession to the Premiership with gladness and hope.

- Thomas Frost, Forty Years' Recollections: Literary and Political (1880), p. 291

- Last night I met Gladstone — it will always be a memorable night to me; Stubbs was there, and Goldwin Smith and Humphrey Sandwith and Mackenzie Wallace whose great book on Russia is making such a stir, besides a few other nice people; but one forgets everything in Gladstone himself, in his perfect naturalness and grace of manner, his charming abandon of conversation, his unaffected modesty, his warm ardour for all that is noble and good. I felt so proud of my leader — the chief I have always clung to through good report and ill report — because, wise or unwise as he might seem in this or that, he was always noble of soul. He was very pleasant to me, and talked of the new historic school he hoped we were building as enlisting his warmest sympathy. I wish you could have seen with what a glow he spoke of the Montenegrins and their struggle for freedom; how he called on us who wrote history to write what we could of that long fight for liberty! And all through the evening not a word to recall his greatness amongst us, simple, natural, an equal among his equals, listening to every one, drawing out every one, with a force and a modesty that touched us more than all his power.

- John Richard Green to Miss Stopford (21 February 1877), as quoted in Letters of John Richard Green (1901) by Leslie Stephen, p. 446

- If you were to put that man on a moor with nothing on but his shirt, he would become whatever he pleased.

- T. H. Huxley, quoted in Lord Robert Cecil's Goldfields Diary, ed. Ernest Scott (1945)

- I don't object to Gladstone always having the ace of trumps up his sleeve, but merely to his belief that the Almighty put it there.

- Henry Labouchere, quoted in Hesketh Pearson, Lives of the Wits (1962)

- The greatest Chancellor of all time.

- Nigel Lawson, The View From No. 11: Memoirs of a Tory Radical (1992), p. 279

- It is my boast that for the first four years of my membership of the House of Commons Gladstone was my leader. ... Gladstone was the greatest and most vital figure which ever appeared in British politics, and there will be a glorious resurrection for the memory, character, and the achievement and inspiration of that old man. We are suffering today largely from the complete neglect of the doctrines to which he devoted his life – the doctrines of peace.

- David Lloyd George in conversation with A. J. Sylvester (24 April 1940), quoted in Colin Cross (ed.), Life with Lloyd George. The Diary of A. J. Sylvester 1931-45 (London: Macmillan, 1975), p. 257

- He has one gift most dangerous to a spectator, a vast command of a kind of language, grave and majestic, but of vague and uncertain import.

- Thomas Babington Macaulay, "Gladstone on Church and State," Edinburgh Review (April 1839)

- No body of men have ever been so "un-English" as the great Englishmen, Nelson, Shelley, Gladstone: supreme in war, in literature, in practical affairs; yet with no single evidence in the characteristics of their energy that they possess any of the qualities of the English blood. But in submitting to the leadership of such perplexing variations from the common stock, the Englishman is merely exhibiting his general capacity for accepting the universe, rather than for rebelling against it.

- C.F.G. Masterman, The Condition of England, (1909).

- Respecting Mr. Gladstone (Cheers). What was the use to speak of him on a question of sincerity? (Cheers). Every year of his official life had been marked by a succession of measures – no year being without them – some great, some small, but all aiming at the public good – to the good of the people of this country, and especially of the poorer classes. These measures were not even suggested to him: they were the offspring of his own mind, will and purpose – the free gift from him to his countrymen, unprompted, unsuggested. (Loud cheers). ... Mr. Gladstone seemed to be the first statesman who has come up to the idea of a great modern statesman: ... If we do not stand by him...we shall not easily find another to serve us in the same way. (Loud cheers).

- John Stuart Mill, speech to the Westminster Reform meeting, Daily Telegraph (13 April 1866), quoted in John Vincent, The Formation of the British Liberal Party, 1857–1868 (Pelican, 1972), p. 194.

- On the afternoon of the first of December [1868], he received at Hawarden the communication from Windsor. “I was standing by him,” says Mr. Evelyn Ashley, “holding his coat on my arm while he in his shirt sleeves was wielding an axe to cut down a tree. Up came a telegraph messenger. He took the telegram, opened it and read it, then handed it to me, speaking only two words, ‘Very significant,’ and at once resumed his work. The message merely stated that General Grey would arrive that evening from Windsor. This of course implied that a mandate was coming from the Queen charging Mr. Gladstone with the formation of his first government. ... After a few minutes the blows ceased, and Mr. Gladstone resting on the handle of his axe, looked up and with deep earnestness in his voice and with great intensity in his face, exclaimed, ‘My mission is to pacify Ireland.’ He then resumed his task, and never said another word till the tree was down.”

- John Morley, The Life of William Ewart Gladstone: Vol. II. (1859-1880) (Toronto: George N. Morang & Company, Limited, 1903), p. 252

- Gladstone will soon have it all his own way and whenever he gets my place we shall have strange doings.

- Lord Palmerston to Lord Shaftesbury towards the end of Palmerston's life. E. Hodder, The Life and Work of the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury: Volume III (1886), p. 187

- [A]s these letters show, the man whom above all others Lord Acton esteemed and revered was Mr. Gladstone. Mr. Gladstone, with characteristic humility, always deferred to Lord Acton's judgment in matters historical. On the other hand, Lord Acton, the most hypercritical of men, and the precise opposite of a hero-worshipper, an iconoclast if ever there was one, regarded Mr. Gladstone as the first of English statesmen, living or dead.

- Herbert Paul, Introductory Memoir, Letters of Lord Acton to Mary, Daughter of the Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone (1904) p. lx.

- The defects of his strength grow on him. All black is very black, all white very white.

- Lord Rosebery, diary entry (4 August 1887)

- Something like a little amicable duel took place at one time between Ruskin and Mr. G., when Ruskin directly attacked his host as a “leveller.” “You see you think one man is as good as another and all men equally competent to judge aright on political questions; whereas I am a believer in an aristocracy.” And straight came the answer from Mr. Gladstone, “Oh dear, no! I am nothing of the sort. I am a firm believer in the aristocratic principle — the rule of the best. I am an out-and-out inequalitarian,” a confession which Ruskin treated with intense delight, clapping his hands triumphantly.

- John Ruskin's account of a dinner with Gladstone on 14 December 1878, published in Life of William Ewart Gladstone Volume II (1903) by John Morley, p. 582