A gram of experience is worth a ton of theory.

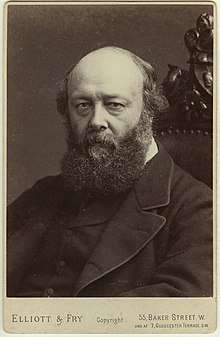

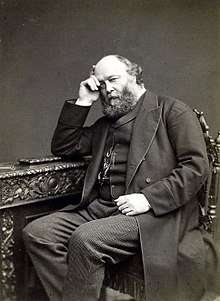

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (3 February 1830 – 22 August 1903) was a British Conservative politician and Prime Minister.

Quotes

No lesson seems to be so deeply inculcated by the experience of life as that you should never trust experts.

1850s

- We are not the same people that we have been, either in our social characteristics, in our patriotic sentiments, or in the tone of our moral and religious feelings.

- Speech at the Oxford Union (February 1850), from H. A. Morrah, The Oxford Union. 1823-1923 (1923), p. 139

- A gram of experience is worth a ton of theory.

- Saturday Review (1859)

- ...the splitting up of mankind into a multitude of infinitesimal governments, in accordance with their actual differences of dialect or their presumed differences of race, would be to undo the work of civilisation and renounce all the benefits which the slow and painful process of consolidation has procured for mankind...It is the agglomeration and not the comminution of states to which civilisation is constantly tending; it is the fusion and not the isolation of races by which the physical and moral excellence of the species is advanced. There are races, as there are trees, which cannot stand erect by themselves, and which, if their growth is not hindered by artificial constraints, are all the healthier for twining round some robuster stem.

- Bentley's Quarterly Review, 1, (1859), p. 22

- ...though it is England's right to enforce the law of Europe [i.e. treaties] as between contending states, she has no claim, so long as her own interests are untouched, to interfere in the national affairs of any country, whatever the extent of its misgovernment or its anarchy.

- Bentley's Quarterly Review, 1, (1859), p. 23

- Not the number of noses, but the magnitude of interests, should furnish the elements by which the proportion of representation should be computed...The classes that represent civilisation, the holders of accumulated capital and accumulated thought have a right to require securities to protect them from being overwhelmed by hordes who have neither knowledge to guide them nor stake in the Commonwealth to control them.

- Bentley's Quarterly Review, 1, (1859), pp. 28-29

- The days and weeks of screwed-up smiles and laboured courtesy, the mock geniality, the hearty shake of the filthy hand, the chuckling reply that must be made to the coarse joke, the loathsome, choking compliment that must be paid to the grimy wife and sluttish daughter, the indispensable flattery of the vilest religious prejudices, the wholesale deglutition of hypocritical pledges.

- On canvassing for election. Bentley's Quarterly Review, 1, (1859), p. 355

1860s

- ...the vista of an age of security and peace – disbanded armaments, forgotten jealousies, immunity not only from the scourge but from the panic of war; pleasant dreams, constantly belied by experience, constantly renewed by theorists, but too closely linked to the hopes of all who believe either in material progress or in the promises of religion ever to be abandoned as chimera.

- Quarterly Review, 107, 1860, p. 516

- Wherever democracy has prevailed, the power of the State has been used in some form or other to plunder the well-to-do classes for the benefit of the poor.

- Quarterly Review, 107, 1860, p. 524

- It was a part of a budget which even three months had proved to be a mass of miscalculation; it was the pet scheme of a cosmopolitan school who love England little, and whom England loves less, whose sympathies are half-American and half-French; and it was the first application of a theory of combined taxation and reform, according to which the poor were exclusively to fix the revenue which the rich were exclusively to pay.

- ‘The Conservative Reaction’, The Quarterly Review, vol. 108 (July & October 1860), p. 276

- First-rate men will not canvass mobs; and if they did, the mobs would not elect the first-rate men.

- Quarterly Review, 110, 1861, p. 281

- In the supreme struggle of social order against anarchy, we cannot deny to the champions of civilised society the moral latitude which is by common consent accorded to armed men fighting for their country against a foreign foe.

- On Lord Castlereagh's use of bribery to pass the Irish Act of Union. Quarterly Review, 111, 1862, p. 204

- ...the gentleness, the concessions, the morbid tenderness of Louis XVI had only tended to precipitate his own and his people's doom, and aggravate the ferocity of those he tried by kindness to disarm.

- Quarterly Review, 111, 1862, pp. 538-539

- The struggle for power in our day lies not between Crown and people, or between a caste of nobles and a bourgeoisie, but between the classes who have property and the classes who have none.

- Quarterly Review, 112, 1862, p. 542

- Political equality is not merely a folly – it is a chimera. It is idle to discuss whether it ought to exist; for, as a matter of fact, it never does. Whatever may be the written text of a Constitution, the multitude always will have leaders among them, and those leaders not selected by themselves. They may set up the pretence of political equality, if they will, and delude themselves with a belief of its existence. But the only consequences will be, that they will have bad leaders instead of good. Every community has natural leaders, to whom, if they are not misled by the insane passion for equality, they will instinctively defer. Always wealth, in some countries by birth, in all intellectual power and culture, mark out the men whom, in a healthy state of feeling, a community looks to undertake its government. They have the leisure for the task, and can give it the close attention and the preparatory study which it needs. Fortune enables them to do it for the most part gratuitously, so that the struggles of ambition are not defiled by the taint of sordid greed. They occupy a position of sufficient prominence among their neighbours to feel that their course is closely watched, and they belong to a class brought up apart from temptations to the meaner kinds of crime, and therefore it is no praise to them if, in such matters, their moral code stands high. But even if they be at bottom no better than others who have passed though greater vicissitudes of fortune, they have at least this inestimable advantage – that, when higher motives fail, their virtue has all the support which human respect can give. They are the aristocracy of a country in the original and best sense of the word. Whether a few of them are decorated by honorary titles or enjoy hereditary privileges, is a matter of secondary moment. The important point is, that the rulers of the country should be taken from among them, and that with them should be the political preponderance to which they have every right that superior fitness can confer. Unlimited power would be as ill-bestowed upon them as upon any other set of men. They must be checked by constitutional forms and watched by an active public opinion, lest their rightful pre-eminence should degenerate into the domination of a class. But woe to the community that deposes them altogether!

- Quarterly Review, 112, 1862, pp. 547-548

- ...that shapeless, formless, fibreless mass of platitudes which in official cant is called "unsectarian religion".

- Quarterly Review, 113, 1863, p. 266

- Wherever it has had free play in the ancient world or in the modern, in the old hemisphere or the new, a thirst for empire, and a readiness for aggressive war, has always marked it.

- On democracy. Quarterly Review, 115, 1864, p. 239

- In the real business of life no one troubles himself much about 'moral titles'. No one would dream of surrendering any practical security, for the advantages of which he is actually in possession, in deference of the a priori jurisprudence of a whole Academy of philosophers.

- Quarterly Review, 116, 1864, p. 263

- [Property furnishes] almost the only motive power of agitation. A violent political movement (setting aside those where religious controversy is at work) is generally only an indication that a class of those who have little see their way to getting more by means of a political convulsion.

- Quarterly Review, 116, 1864, pp. 265-266

- To give 'the suffrage' to a poor man is to give him as large a part in determining that legislation which is mainly concerned with property as the banker whose name is known on every Exchange in Europe, as the merchant whose ships are in every sea, as the landowner who owns the soil of a whole manufacturing town...two day-labourers shall outvote Baron Rothschild...The bestowal upon any class of a voting power disproportionate to their stake in the country, must infallibly give that class a power pro tanto of using taxation as an instrument of plunder, and expenditure and legislation as a fountain of gain.

- Quarterly Review, 116, 1864, p. 266, pp. 269-270

- ...the common sense of Christendom has always prescribed for national policy principles diametrically opposed to those that are laid down in the Sermon on the Mount.

- Saturday Review, 17, 1864, pp. 129–30

- The perils of change are so great the promise of the most hopeful theories is so often deceptive, that it is frequently the wiser part to uphold the existing state of things, if it can be done, even though, in point of argument, it should be utterly indefensible...Resistance is folly or heroism—a virtue or a vice—in most cases, according to the probabilities there are of its being successful.

- Quarterly Review, 117, 1865, p. 550

- A Government which is strong enough to hold its own will generally command an acquiescence which with all but very speculative minds, is the equivalent of contentment.

- Quarterly Review, 117, 1865, p. 550

- Conflict in free states is the law of life.

- Quarterly Review, 118, 1865, p. 198

- Opinions upon moral questions are more often the expression of strongly felt expediency than of careful ethical reasoning; and the opinions so formed by one generation become the conscientious convictions or the sacred instincts of the next.

- Saturday Review, 29, 1865, p. 532

- We might as well hope for the termination of the struggle for existence by which, some philosophers tell us, the existence or the modification of the various species of organized beings upon our planet are determined. The battle for political power is merely an effort, well or ill-judged, on the part of the classes who wage it to better or to secure their own position. Unless our social activity shall have become paralyzed, and the nation shall have lost its vitality, this battle must continue to rage. In this sense the question of reform, that is to say, the question of relative class power, can never be settled.

- Quarterly Review, 120, 1866, p. 273

- It is said,—and men seem to think that condemnation can go no further than such a censure—that they brought us within twenty-four hours of revolution...But is it in truth so great an evil, when the dearest interests and the most sincere convictions are at stake, to go within twenty-four hours of revolution?

- On resistance to the Reform Act 1832. Quarterly Review, 123, 1867, p. 557

- There can be no finality in politics.

- Quarterly Review, 123, 1867, p. 557

- I have for so many years entertained a firm conviction that we were going to the dogs that I have got to be quite accustomed to the expectation.

- Letter to H. W. Acland (4 February 1867), from G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume I, p. 211

- He ventured to enter his most earnest protest against the mode in which several Members of that House were inclined to treat anything that ran out of the common ruck—and introduced them to schemes and ideas which former debates had not reached. The scheme of the hon. Gentleman was not new—he should not have thought that it was new to many Members of that House; the literature of the country had been full of it for three or four years. They all instinctively felt that it was a scheme that had no chance of success. It was not of our atmosphere—it was not in accordance with our habits; it did not belong to us. They all knew that it could not pass. Whether that was creditable to the House or not was a question into which he would not inquire; but every Member of the House the moment he saw the scheme upon the Paper saw that it belonged to the class of impracticable things.

- Speech in the House of Commons (30 May 1867) against John Stuart Mill's proposal for electing MPs by proportional representation

- The Lieutenant Governor of Bengal was to the fullest extent responsible for not having made any preparation against the famine...The doctrines of political economy had been worshipped as a sort of "fetish" by officials who, because they believed that in the long run supply and demand would square themselves, seemed to have utterly forgotten that human life was short, and that men could not subsist without food beyond a few days. They mechanically left the laws of political economy to work themselves out while hundreds of thousands of human beings were perishing from famine.

- Speech in the House of Commons (2 August 1867) on the Orissa famine of 1866

- The great evil, and it was a hard thing to say, was that English officials in India, with many very honourable exceptions, did not regard the lives of the coloured inhabitants with the same feeling of intense sympathy which they would show to those of their own race, colour, and tongue. If that was the case it was not their fault alone. Some blame must be laid upon the society in which they had been brought up, and upon the public opinion in which they had been trained. It became them to remember that from that place, more than from any other in the kingdom, proceeded that influence which formed the public opinion of the age, and more especially that kind of public opinion which governed the action of officials in every part of the Empire. If they would have our officials in distant parts of the Empire, and especially in India, regard the lives of their coloured fellow-subjects with the same sympathy and with the same zealous and quick affection with which they would regard the lives of their fellow-subjects at home, it was the Members of that House who must give the tone and set the example. That sympathy and regard must arise from the zeal and jealousy with which the House watched their conduct and the fate of our Indian fellow-subjects. Until we showed them our thorough earnestness in this matter—until we were careful to correct all abuses and display our own sense that they are as thoroughly our fellow-subjects as those in any other part of the Empire, we could not divest ourselves of all blame if we should find that officials in India did treat with something of coldness and indifference such frightful calamities as that which had so recently happened in that country.

- Speech in the House of Commons (2 August 1867) on the Orissa famine of 1866

- We have heard from the opposite Bench several very animated appeals to this House, and several constitutional lectures as to our duties. The noble Earl the late Foreign Secretary (the Earl of Clarendon) went so far, as I understood him, as to tell us that we must watch public opinion more closely, and pay greater attention to the majorities in the other House of Parliament. My Lords, it occurs to me to ask the noble Earl whether he has considered for what purpose this House exists, and whether he would be willing to go through the humiliation of being a mere echo and supple tool of the other House in order to secure for himself the luxury of mock legislation? I agree with my noble Friend the noble Earl (the Earl of Derby) below me that it were better not to be than submit to such a slavery.

- Speech in the House of Lords (26 June 1868)

- On...rare and great occasions, on which the national mind has fully declared itself, I do not doubt your Lordships would yield to the opinion of the country—otherwise the machinery of Government could not be carried on. But there is an enormous step between that and being the mere echo of the House of Commons...I have no fear of the conduct of the House of Lords in this respect. I am quite sure—whatever judgment may be passed on us, whatever predictions may be made, be your term of existence long or short—you will never consent to act except as a free, independent House of the Legislature, and that you will consider any other more timid or subservient course as at once unworthy of your traditions, unworthy of your honour, and, most of all, unworthy of the nation you serve.

- Speech in the House of Lords (26 June 1868)

- Social stability is ensured, not by the cessation of the demand for change – for the needy and the restless will never cease to cry for it – but by the fact that change in its progress must at last hurt some class of men who are strong enough to arrest it. The army of so-called reform, in every stage of its advance, necessarily converts a detachment of its force into opponents. The more rapid the advance the more formidable will the desertion become, till at last a point will be reached where the balance between the forces of conservation and destruction will be redressed, and the political equilibrium be restored.

- Quarterly Review, 127, 1869, pp. 551-552

- To act the part of the fulcrum from which the least Radical portion of the party opposed to them can work upon their friends and leaders, is undoubtedly not an attractive future...it may well end in the moderate Liberals enjoying a permanent tenure of office, propped up mainly by their support...Yet it is the only policy by which the Conservatives can now effectively serve their country.

- Quarterly Review, 127, 1869, p. 560

1870s

- The revolution of 1832 was, therefore, in its ultimate results, a democratic revolution, though its earlier form was transitional and incomplete. This form was productive of great advantages for the time: indeed, for some years it might be said, without exaggeration, that the accidental equilibrium of political forces which it had produced presented the highest ideal of internal government the world had hitherto seen. But it was not the less provisional on that account. The forces by which political organisms are destroyed were, for the time, balanced by influences which still lingered, and were, therefore, neutralised. But these were increasing, and the others were decaying, and the balance could not last for any length of time. It has now been finally upset, and we have now fully reached the phase of political transformation to which the revolution of 1832 logically led.

- Quarterly Review, 130, 1871, pp. 279-280

- So long as we have government by party, the very notion of repose must be foreign to English politics. Agitation is, so to speak, endowed in this country. There is a standing machinery for producing it. There are rewards which can only be obtained by men who excite the public mind, and devise means of persuading one set of persons that they are deeply injured by another. The production of cries is encouraged by a heavy bounty. The invention and exasperation of controversies lead those who are successful in such arts to place, and honour, and power. Therefore, politicians will always select the most irritating cries, and will raise the most exasperating controversies the circumstances will permit.

- Quarterly Review, 131, 1873, p. 578

- The two parties represent two opposite moods of the English mind, which may be trusted, unless past experience is wholly useless, to succeed each other from time to time. Neither of them, neither the love of organic changes nor the dislike of it, can be described as normal to a nation. In every nation, they have succeeded each other at varying intervals during the whole of the period which separates its birth from its decay. Each finds in the circumstances and constitution of individuals a regular support which never deserts it. Among men, the old, the phlegmatic, the sober-minded, among classes, those who have more to lose than to gain by change, furnish the natural Conservatives. The young, the envious, the restless, the dreaming, those whose condition cannot easily be made worse, will be rerum novarum cupidi. But the two camps together will not nearly include the nation: for the vast mass of every nation is unpolitical.

- Quarterly Review, 133, 1872, pp. 583-584

- ...the central doctrine of Conservatism, that it is better to endure almost any political evil than to risk a breach of the historic continuity of government.

- Quarterly Review, 135, 1873, p. 544

- One thing at least is clear—that no one believes in our good intentions. We are often told to secure ourselves by their affections, not by force. Our great-grand children may be privileged to do it, but not we.

- Letter to Lord Northbrook (28 May 1874) on British rule in India, quoted in S. Gopal, British Policy in India, 1858-1905 (Cambridge University Press, 1965), p. 65

- [Permitting discussions in the Indian Council seems to me] an unmeaning mimicry of the forms of popular institutions where the reality is impossible. What is called public opinion in India is frequently the opinion of a clique, and presents none of the guarantees for sound judgment possessed by a public opinion which represents the combined views of a large mass of different interests and classes. I have the smallest possible belief in 'Councils' possessing any other than consultative functions.

- Letter to Lord Northbrook (12 June 1874), quoted in S. Gopal, British Policy in India, 1858-1905 (Cambridge University Press, 1965), p. 104.

- Speaking generally, I am desirous to push forward the argument from the interests of the people more than has hitherto been done. As I have said, I consider it to be our true rule and measure of action, and our observance of it is the one justification for our presence in India.

- Letter to Lord Northbrook (25 August 1875), quoted in S. Gopal, British Policy in India, 1858-1905 (Cambridge University Press, 1965), p. 65

- If England is to remain supreme, she must be able to appeal to the coloured against the white, as well to the white against the coloured. It is therefore not merely as a matter of sentiment and of justice, but as a matter of safety, that we ought to try and lay the foundation of some feeling on the part of coloured races towards the crown other than the recollection of defeat and the sensation of subjection.

- Letter to the Viceroy of India Lord Lytton (7 July 1876), quoted in S. Gopal, British Policy in India, 1858-1905 (Cambridge University Press, 1965), p. 115

- It is clear enough that the traditional Palmerstonian policy [of British support for Ottoman territorial integrity] is at an end.

- Salisbury to Disraeli (September 1876), from G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume II, p. 85

- English policy is to float lazily downstream, occasionally putting out a diplomatic boat-hook to avoid collisions.

- Letter to Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton (9 March 1877), as quoted in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume II, p. 130

- The commonest error in politics is sticking to the carcass of dead policies.

- Letter to Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton (25 May 1877), as quoted in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume II, p. 145

- I would have devoted my whole efforts to securing the waterway to India – by the acquisition of Egypt or of Crete, and would in no way have discouraged the obliteration of Turkey.

- Letter to Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton (15 June 1877), from G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume II, pp. 145-146

- No lesson seems to be so deeply inculcated by the experience of life as that you should never trust experts. If you believe doctors, nothing is wholesome: if you believe the theologians, nothing is innocent: if you believe the soldiers, nothing is safe. They all require their strong wine diluted by a very large admixture of insipid common sense.

- Letter to Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton (15 June 1877), as quoted in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (1999) Elizabeth M. Knowles, p. 642; this has also been published without the word "insipid".

- Salisbury said two things which are more decided than any former utterances of his: that Russia at Constantinople would do us no harm: and that we ought to seize Egypt.

- Salisbury to the Cabinet (16 June 1877), from John Vincent (ed.), The Diaries of Edward Henry Stanley, Fifteenth Earl of Derby (London: The Royal Historical Society, 1994), p. 410

- ...if our ancestors had cared for the rights of other people, the British empire would not have been made.

- Salisbury to the Cabinet (8 March 1878), from John Vincent (ed.), The Diaries of Edward Henry Stanley, Fifteenth Earl of Derby (London: The Royal Historical Society, 1994), p. 523

1880s

- ...as individuals and as nations we live in states of society utterly different from each other. As a collection of individuals, we live under the highest and latest development of civilization, in which the individual is rigidly forbidden to defend himself, because society is always ready and able to defend him. As a collection of nations we live in an age of the merest Faustrecht, in which each one obtains his rights precisely in proportion to his ability, or that of his allies, to fight for them...In practice it is found that International Law is always on the side of strong battalions...It is puerile...to apply to the dealings of a nation with its neighbour's territory the morality which would be applicable to two individuals possessing adjoining property, and protected from mutual wrong by a law superior to both.

- Quarterly Review, 151, 1881, pp. 542-544

- I earnestly hope that the House of Lords will always continue to justify your confidence; that it will conscientiously and firmly fulfil the duties for which I think it is eminently fitted, and which are to represent the permanent and enduring wishes of the nation as opposed to the casual impulses which some passing victory at the polls may in some circumstances have given to the decisions of the other House.

- Speech at Newcastle-upon-Tyne (11 October 1881), from The Times (12 October 1881), p. 7

- Much has been said in the present debate about conciliation and the value of conciliatory measures to Ireland...Conciliatory legislation is infinitely superior; but it depends for its efficacy on the circumstances under which it is used, and on the manner in which it is applied. Deterrent legislation, if vigorous and strong, at least deters, whatever the value of that process may be. But conciliatory legislation only conciliates where there is a full belief on the part of those with whom you are dealing that you are acting on a principle of justice, and not that you are acting on motives of fear. Where there is a suspicion or a strong belief that your conciliatory measures have been extorted from you by the violence which they are meant to put a stop to, all the value of that conciliation is taken away.

- Speech in the House of Lords (5 June 1882)

- It is right to be forward in the defence of the poor; no system that is not just as between rich and poor can hope to survive.

- Speech at Edinburgh (24 November 1882), from in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume III, p. 65

- A party whose mission is to live entirely upon the discovery of grievances are apt to manufacture the element upon which they subsist.

- Speech at Edinburgh (24 November 1882), from in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume III, p. 65

- As I have said, there are two points or two characteristics of the Radical programme which it is your special duty to resist. One concerns the freedom of individuals. After all, the great characteristic of this country is that it is a free country, and by a free country I mean a country where people are allowed, so long as they do not hurt their neighbours, to do as they like. I do not mean a country where six men may make five men do exactly as they like. That is not my notion of freedom.

- Speech to the third annual banquet of the Kingston and District Working Men's Conservative Association (13 June, 1883), quoted in 'The Marquis Of Salisbury At Kingston', The Times (14 June 1883), p. 7

- It is patent on the face of history that the aggregates of men who form communities, like the aggregates of atoms that form living bodies, are subject to laws of progressive change – be it towards growth or towards decay.

- Quarterly Review, 156, 1883, p. 570

- Half a century ago, the first feeling of all Englishmen was for England. Now, the sympathies of a powerful party are instinctively given to whatever is against England. It may be Boers or Baboos, or Russians or Affghans, or only French speculators – the treatment these all receive in their controversies with England is the same: whatever else my fail them, they can always count on the sympathies of the political a party from whom during the last half century the rulers of England have been mainly chosen...It is striking, though by no means a solitary indication of how low, in the present temper of English politics, our sympathy with our own countrymen has fallen. Of course, we shall be told that a conscience of exalted sensibility, which is the special attribute of the Liberal party, has enabled them to discover, what English statesmen had never discovered before, that the cause to which our countrymen are opposed is generally the just one...For ourselves, we are rather disposed to think that patriotism has become in some breasts so very reasonable an emotion, because it is ceasing to be an emotion at all; and that these superior scruples, to which our fathers were insensible, and which always make the balance of justice lean to the side of abandoning either our territory or our countrymen, indicate that the national impulses which used to make Englishmen cling together in face of every external trouble are beginning to disappear.

- ‘Disintegration’, Quarterly Review, no. 312; October 1883, reprinted in Paul Smith (ed.), Lord Salisbury on Politics. A selection from his articles in the Quaterly Review, 1860-1883 (Cambridge University Press, 1972), pp. 342-343

- ...when I am told that my ploughmen are capable citizens, it seems to me ridiculous to say that educated women are not just as capable. A good deal of the political battle of the future will be a conflict between religion and unbelief: & the women will in that controversy be on the right side.

- Letter to Lady John Manners (14 June 1884), from Paul Smith (ed.), Lord Salisbury on politics: a selection from his articles in the Quarterly Review, 1860–83 (1972), p. 18, footnote

- Mr. Parnell said the other night, that Ireland is a "nation". Well, if a nation only means a certain number of individuals collected between certain latitudes and longitudes, I admit in that sense Ireland is a nation. But if there is anything further necessary—if to make a nation you require a past united history, traditions in which you can all join, achievements of which you all are proud, interests which you share in common, and sympathies which belong to all—then emphatically Ireland is not a nation; Ireland is two nations.

- Speech to the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations in St. James's Hall, London (15 May 1886), quoted in The Times (17 May 1886), p. 6

- Confidence depends upon the people in whom you are to confide. You would not confide free representative institutions to the Hottentots, for instance. Nor, going higher up the scale, would you confide them to the Oriental nations whom you are governing in India—although finer specimens of human character you will hardly find than some of those who belong to these nations, but who are simply not suited to the particular kind of confidence of which I am speaking. Well, I doubt whether you could confide representative institutions to the Russians with any great security. You have done it to the Greeks, but I do not know whether the result has been absolutely what you wish. And when you come to narrow it down you will find that this which is called self-government, but which is really government by the majority, works admirably well when it is confided to people who are of Teutonic race, but that it does not work so well when people of other races are called upon to join in it.

- Speech to the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations in St. James's Hall, London (15 May 1886), quoted in The Times (17 May 1886), p. 6

- If they will abandon the habit of mutilating, murdering, robbing, and of preventing honest persons who are attached to England from earning their livelihood, they may be sure there will be no demand for coercion. Well, you will be told you have no alternative policy. My alternative policy is that Parliament should enable the Government of England to govern Ireland. Apply that recipe honestly, consistently, and resolutely for 20 years, and at the end of that time you will find that Ireland will be fit to accept any gifts in the way of local government or repeal of coercion laws that you may wish to give her. What she wants is government—government that does not flinch, that does not vary—government that she cannot hope to beat down by agitations at Westminster—government that does not alter in its resolutions or its temperature by the party changes which take place at Westminster.

- Speech to the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations in St. James's Hall, London (15 May 1886), quoted in The Times (17 May 1886), p. 6. The Liberal MP John Morley responded by claiming that Salisbury was in favour of "20 years of coercion" for Ireland, which Salisbury contested.

- The business which brings you here to-day is of a peculiar character, due to the very peculiar character of the Empire over which the Queen rules. It yields to none, it is perhaps superior to all in its greatness, in its extent, in the vastness of its population, in the magnificence of its wealth. But it has this peculiarity which separates it from other empires—the want of continuity. The Empire is separated into parts, and distant parts, by large stretches of ocean, and what we are really here to do is to see how far we must acquiesce in the conditions which that separation causes, how far we can obliterate them by agreement and by organization.

- Speech to the Colonial Conference, London (4 April 1887), quoted in The Times (5 April 1887), p. 11

- On general grounds I object to Parliament trying to regulate private morality in matters which only affects the person who commits the offence.

- Letter to Sir Henry Peek (1888)

- ...institutions like the House of Lords must die, like all other organic beings, when their time comes.

- Letter to Alfred Austin (29 April 1888), from Paul Smith (ed.), Lord Salisbury on politics: a selection from his articles in the Quarterly Review, 1860–83 (1972), p. 39, footnote

1890s

- Parliament is a potent engine, and its enactments must always do something, but they very seldom do what the originators of these enactments meant.

- Statement to the Associated Chambers of Commerce (March 1891)

- [Most legislation] will have the effect of surrounding the industry which it touches with precautions and investigations, inspections and regulations, in which it will be slowly enveloped and stifled.

- Statement to the Associated Chambers of Commerce (March 1891)

- There is no danger which we have to contend with which is so serious as an exaggeration of the power, the useful power, of the interference of the State. It is not that the State may not or ought not to interfere when it can do so with advantage, but that the occasions on which it can so interfere are so lamentably few and the difficulties that lie in its way are so great. But I think that some of us are in danger of an opposite error. What we have to struggle against is the unnecessary interference of the State, and still more when that interference involves any injustice to any people, especially to any minority. All those who defend freedom are bound as their first duty to be the champions of minorities, and the danger of allowing the majority, which holds the power of the State, to interfere at its will is that the interests of the minority will be disregarded and crushed out under the omnipotent force of a popular vote. But that fear ought not to lead us to carry our doctrine further than is just. I have heard it stated — and I confess with some surprise — as an article of Conservative opinion that paternal Government — that is to say, the use of the machinery of Government for the benefit of the people — is a thing in itself detestable and wicked. I am unable to subscribe to that doctrine, either politically or historically. I do not believe it to have been a doctrine of the Conservative party at any time. On the contrary, if you look back, even to the earlier years of the present century, you will find the opposite state of things; you will find the Conservative party struggling to confer benefits — perhaps ignorantly and unwisely, but still sincerely — through the instrumentality of the State, and resisted by a severe doctrinaire resistance from the professors of Liberal opinions. When I am told that it is an essential part of Conservative opinion to resist any such benevolent action on the part of the State, I should expect Bentham to turn in his grave; it was he who first taught the doctrine that the State should never interfere, and any one less like a Conservative than Bentham it would be impossible to conceive... The Conservative party has always leaned — perhaps unduly leaned — to the use of the State, as far as it can properly be used, for the improvement of the physical, moral, and intellectual condition of our people, and I hope that that mission the Conservative party will never renounce, or allow any extravagance on the other side to frighten them from their just assertion of what has always been its true and inherent principles.

- Speech to the United Club (15 July, 1891), published in "Lord Salisbury On Home Politics" in The Times (16 July 1891), p. 10

- We must learn this rule, which is true alike of rich and poor — that no man and no class of men ever rise to any permanent improvement in their condition of body or of mind except by relying upon their own personal efforts. The wealth with which the rich man is surrounded is constantly tempting him to forget the truth, ad you see in family after family men degenerating from the position of their fathers because they live sluggishly and enjoy what has been placed before them without appealing to their own exertions. The poor man, especially in these days, may have a similar temptation offered to him by legislation, but this same inexorable rule will work. The only true lasting benefit which the statesman can give to the poor man is so to shape matters that the greatest possible opportunity for the exercise of his own moral and intellectual qualities shall be offered to him by the law; and therefore it is that in my opinion nothing that we can do this year, and nothing that we did before, will equal in the benefit that it will confer upon the physical condition, and with the physical will follow the moral too, of the labouring classes in the rural districts, that measure for free education which we passed last year. It will have the effect of bringing education home to many a family which hitherto has not been able to enjoy it, and in that way, by developing the faculties which nature has given to them, it will be a far surer and a far more valuable aid to extricate them from any of the sufferings or hardships to which they may be exposed than the most lavish gifts of mere sustenance that the State could offer.

- Speech to Devonshire Conservatives (January 1892), as quoted in The Marquis of Salisbury (1892), by James J. Ellis, p. 185

- Variant: The only true lasting benefit which the statesman can give to the poor man is so to shape matters that the greatest possible liberty for the exercise of his own moral and intellectual qualities should be offered to him by law.

- As quoted in Salisbury — Victorian Titan (1999) by Andrew Roberts

- I feel it is our duty to sustain the federated action of Europe. I think it has suffered by the somewhat absurd name which has been given to it—the Concert of Europe—and the intense importance of the fact has been buried under the bad jokes to which the word has given rise. But the federated action of Europe—if we can maintain it, if we can maintain this Legislature—is our sole hope of escaping from the constant terror and the calamity of war, the constant pressure of the burdens of an armed peace which weigh down the spirits and darken the prospects of every nation in this part of the world. ["Hear, hear!"] The federation of Europe is the only hope we have; but that federation is only to be maintained by observing the conditions on which every Legislature must depend, on which every judicial system must be based—the engagements into which it enters must be respected.

- Speech in the House of Lords (19 March 1897)

- You must remember what the concert of Europe is. The concert, or, as I prefer to call it, the inchoate federation of Europe, is a body which acts only when it is unanimous...remember this—that this federation of Europe is the embryo of the only possible structure of Europe which can save civilization from the desolating effects of a disastrous war. (Cheers.) You notice that on all sides the instruments of destruction, the piling up of arms, are becoming larger and larger. The powers of concentration are becoming greater, the instruments of death more active and more numerous, and are improved with every year; and each nation is bound, for its own safety's sake, to take part in this competition. These are the things which are done, so to speak, on the side of war. The one hope that we have to prevent this competition from ending in a terrible effort of mutual destruction which will be fatal to Christian civilization—the one hope we have is that the Powers may gradually be brought together, to act together in a friendly spirit on all questions of difference which may arise, until at last they shall be welded in some international constitution which shall give to the world, as a result of their great strength, a long spell of unfettered and prosperous trade and continued peace.

- Speech at the Guildhall (9 November 1897), quoted in The Times (10 November 1897), p. 6

- I have a strong belief that there is a danger of the public opinion of this country undergoing a reaction from the Cobdenic doctrines of 30 or 40 years ago, and believing that it is our duty to take everything we can, to fight everybody, and to make a quarrel of every dispute. That seems to me a very dangerous doctrine, not merely because it might incite other nations against us—though that is not a consideration to be neglected, for the kind of reputation we are at present enjoying on the Continent of Europe is by no means pleasant, and by no means advantageous; but there is a much more serious danger, and that is lest we should overtax our strength. However strong you may be, whether you are a man or a nation, there is a point beyond which your strength will not go. It is madness; it ends in ruin if you allow yourselves to pass beyond it.

- Speech in the House of Lords (8 February 1898)

- If I were asked to define Conservative policy, I should say that it was the upholding of confidence.

- Quoted in Salisbury — Victorian Titan (1999) by Andrew Roberts

- Mr Mayor and gentlemen - I have great pleasure in associating myself in how ever humble and transitory manner with this great and splendid undertaking. I am glad to be associated with an enterprise which I hope will carry still further the prosperity and power of Liverpool, and which will carry down the name of Liverpool to posterity as the place where a great mechanical undertaking first found its home. Sir William Forwood has alluded to the share which this city took in the original establishment of railways. My memory does not quite carry me back to the melancholy event by which that opening was signalised, but I can remember that which presents to my mind a strange contrast with the present state of things. Almost the earliest thing I can recollect is being brought down here to my mother's house which is close in the neighbourhood, and we took two days on the road, and had to sleep half way. Comparing that with my journey yesterday I feel what an enormous distance has been traversed in the interval, and perhaps a still larger distance and a still more magnificent rate of progress will be achieved before a similar distance of time has elapsed from the present day. I will not detain you in a room where it is perhaps difficult to hear. Of all my oratorical efforts, the one which I find most difficult to achieve is that of competing with a steam engine. Occasionally you are invited to do it at railway stations, and I know distinguished statesmen who do it with effect, but I think I have never ventured to compete in that line. I will therefore, though with some fear and trembling, fulfil the injunctions of Sir William Forwood, and proceed to handle the electric machinery which is to set this line in motion. I only hope the result will be no different from what he anticipates.

- At the opening of the Liverpool Overhead Railway, 4 February 1893. Quoted in the Liverpool Echo of the same day, p. 3

Misattributed

- Solitude shows us what should be; society shows us what we are.

- Richard Cecil, as quoted in Remains of Mr. Cecil (1836) edited by Josiah Pratt, p. 59

- It is one of the misfortunes of our political system that parties are formed more with reference to controversies that are gone by than to the controversies which these parties have actually to decide.

- Statement of an uncredited reviewer in The Quarterly Review [London] (January 1866), p. 277

Quotes about Salisbury

- The most formidable intellectual figure that the Conservative party has ever produced.

- Robert Blake, Disraeli (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1966), p. 499

- The giant of conservative doctrine is Salisbury, with Churchill, Eliot, Disraeli, Waugh and Burke in the 1790s best thought of as trailing in his wake.

- Maurice Cowling, 'The Present Position', Cowling (ed.), Conservative Essays (London: Cassell, 1978), p. 22

- Shortly before he died, I invited Clement Attlee to Chequers ... I asked him, parties and politics apart, whom he regarded the best prime minister qua prime minister since he first took an interest in politics. He had no hesitation – "Salisbury".

- Harold Wilson, The Governance of Britain (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1976), p. 31, n. 2.

External links

- "Lord Salisbury (1830-1903) The Libertarian" by Andrew Roberts

This article is issued from

Wikiquote.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.