_(cropped).jpg)

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid revolutionary, politician, and philanthropist, who served as President of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black chief executive, and the first elected in a fully representative democratic election. His government focused on dismantling the legacy of apartheid through tackling institutionalised racism and fostering racial reconciliation. Politically an African nationalist and democratic socialist, he served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) party from 1991 to 1997. He was the co-winner of the Nobel Peace Prize with F.W. de Klerk in 1993.

Quotes

1960s

- There are thousands of people who feel that it is useless and futile for us to continue talking peace and non-violence — against a government whose only reply is savage attacks on an unarmed and defenceless people. And I think the time has come for us to consider, in the light of our experiences at this day at home, whether the methods which we have applied so far are adequate.

- Ethiopia has always held a special place in my own imagination and the prospect of visiting attracted me more strongly than a trip to France, England and America combined. I felt I would be visiting my own genesis, unearthing the roots of what made me an African. Meeting the emperor himself would be like shaking hands with history.

- On a 1961 conference held in Ethiopia, as quoted in Rivonia Unmasked (1965) by Strydom Lautz, p. 108; also in Rolihlahla Dalibhunga Nelson Mandela : An Ecological Study (2002), by J. C. Buthelezi, p. 172

First court statement (1962)

- Statement on charges of inciting persons to strike illegally, and of leaving the country without a valid passport.

- In its proper meaning equality before the law means the right to participate in the making of the laws by which one is governed, a constitution which guarantees democratic rights to all sections of the population, the right to approach the court for protection or relief in the case of the violation of rights guaranteed in the constitution, and the right to take part in the administration of justice as judges, magistrates, attorneys-general, law advisers and similar positions.

In the absence of these safeguards the phrase 'equality before the law', in so far as it is intended to apply to us, is meaningless and misleading. All the rights and privileges to which I have referred are monopolized by whites, and we enjoy none of them. The white man makes all the laws, he drags us before his courts and accuses us, and he sits in judgement over us.

- It is fit and proper to raise the question sharply, what is this rigid color-bar in the administration of justice? Why is it that in this courtroom I face a white magistrate, am confronted by a white prosecutor, and escorted into the dock by a white orderly? Can anyone honestly and seriously suggest that in this type of atmosphere the scales of justice are evenly balanced?

Why is it that no African in the history of this country has ever had the honor of being tried by his own kith and kin, by his own flesh and blood?

I will tell Your Worship why: the real purpose of this rigid color-bar is to ensure that the justice dispensed by the courts should conform to the policy of the country, however much that policy might be in conflict with the norms of justice accepted in judiciaries throughout the civilised world.

- I hate race discrimination most intensely and in all its manifestations. I have fought it all during my life; I fight it now, and will do so until the end of my days. Even although I now happen to be tried by one whose opinion I hold in high esteem, I detest most violently the set-up that surrounds me here. It makes me feel that I am a black man in a white man's court. This should not be.

I am Prepared to Die (1964)

- Statement in the Rivonia Trial, Pretoria Supreme Court (20 April 1964)

- I must deal immediately and at some length with the question of violence. Some of the things so far told to the Court are true and some are untrue. I do not, however, deny that I planned sabotage. I did not plan it in a spirit of recklessness, nor because I have any love of violence. I planned it as a result of a calm and sober assessment of the political situation that had arisen after many years of tyranny, exploitation, and oppression of my people by the Whites.

- I have already mentioned that I was one of the persons who helped to form Umkhonto. I, and the others who started the organization, did so for two reasons. Firstly, we believed that as a result of Government policy, violence by the African people had become inevitable, and that unless responsible leadership was given to canalize and control the feelings of our people, there would be outbreaks of terrorism which would produce an intensity of bitterness and hostility between the various races of this country which is not produced even by war. Secondly, we felt that without violence there would be no way open to the African people to succeed in their struggle against the principle of white supremacy. All lawful modes of expressing opposition to this principle had been closed by legislation, and we were placed in a position in which we had either to accept a permanent state of inferiority, or to defy the Government. We chose to defy the law. We first broke the law in a way which avoided any recourse to violence; when this form was legislated against, and then the Government resorted to a show of force to crush opposition to its policies, only then did we decide to answer violence with violence...

- But the violence which we chose to adopt was not terrorism. We who formed Umkhonto were all members of the African National Congress, and had behind us the ANC tradition of non-violence and negotiation as a means of solving political disputes. We believe that South Africa belongs to all the people who live in it, and not to one group, be it black or white. We did not want an interracial war, and tried to avoid it to the last minute. If the Court is in doubt about this, it will be seen that the whole history of our organization bears out what I have said, and what I will subsequently say, when I describe the tactics which Umkhonto decided to adopt.

- During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for. But, my lord, if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

- The ANC has never at any period of its history advocated a revolutionary change in the economic structure of the country, nor has it, to the best of my recollection, ever condemned capitalist society.

1970s

- Difficulties break some men but make others. No axe is sharp enough to cut the soul of a sinner who keeps on trying, one armed with the hope that he will rise even in the end.

- Nelson Mandela on challenges, Letter to Winnie Mandela (1 February 1975), written on Robben Island. Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- I like friends who have independent minds because they tend to make you see problems from all angles.

- Nelson Mandela on friendship, From his unpublished autobiographical manuscript written in 1975. Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- I have never regarded any man as my superior, either in my life outside or inside prison.

- Nelson Mandela on equaliy, From a letter to General Du Preez, Commissioner of Prisons, Written on Robben Island, Cape Town, South Africa (12 July 1976). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

1980s

- Only free men can negotiate; prisoners cannot enter into contracts. Your freedom and mine cannot be separated.

- Refusing to bargain for freedom after 21 years in prison, as quoted in TIME (25 February 1985)

1990s

- I stand here before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today. I therefore place the remaining years of my life in your hands.

- Speech on the day of his release, Cape Town (11 February 1990)

- Exercise dissipates tension, and tension is the enemy of serenity. I found that I worked better and thought more clearly when I was in good physical condition, and so training became one of the inflexible disciplines of my life.

- Interview with Gavin Evans, Soweto (15 February 1990) recounted in COVID-19 lockdown: Can you do Nelson Mandela's Robben Island prison cell workout?, 7 April 2020

- In Natal, apartheid is a deadly cancer in our midst, setting house against house, and eating away at the precious ties that bound us together. This strife among ourselves wastes our energy and destroys our unity. My message to those of you involved in this battle of brother against brother is this: take your guns, your knives, and your pangas, and throw them into the sea! Close down the death factories. End this war now!

- Speech to a Rally, Durban (25 February 1990); Republished in: J. C. Buthelezi. Rolihlahla Dalibhunga Nelson Mandela: An Ecological Study, (2002), p. 340

- We are deeply concerned, both in our country and here, of the very large number of dropouts by schoolchildren. This is a very disturbing situation, because the youth of today are the leaders of tomorrow... try as much as possible to remain in school, because education is the most powerful weapon which we can use.

- Speech, Madison Park High School, Boston, 23 June 1990; Partly cited in Remembering Nelson Mandela's Visit To Roxbury at wgbhnews.org, December 5, 2013; and partly cited in "Nelson Mandela’s 1990 visit left lasting impression" by Peter Schworm on bostonglobe.com, December 7, 2013

- Coloured communities would like to see coloured representatives. That is not racism, that is how nature works.

- As quoted in The Sunday Star (29 November 1991), South Africa

- I never think of the time I have lost. I just carry out a programme because it’s there. It’s mapped out for me.

- Nelson Madenla on time, From a conversation with Richard Stangel (3 May 1993). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- Death is something inevitable. When a man has done what he considers to be his duty to his people and his country, he can rest in peace. I believe I have made that effort and that is, therefore, why I will sleep for the eternity.

- On death, in an interview for the documentary Mandela (1994). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- I had no specific belief except that our cause was just, was very strong and it was winning more and more support.

- Nelson Mandela on ideology, Robben Island, Cape Town, South Africa (11 February 1994). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- A critical, independent and investigative press is the lifeblood of any democracy. The press must be free from state interference. It must have the economic strength to stand up to the blandishments of government officials. It must have sufficient independence from vested interests to be bold and inquiring without fear or favour. It must enjoy the protection of the constitution, so that it can protect our rights as citizens.

- Nelson Mandela on freedom of expression, At the international press institute congress (14 February 1994). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- It is in the character of growth that we should learn from both pleasant and unpleasant experiences.

- Nelson Mandela on character, Foreign Correspondent's Association's Annual Dinner, Johannesburg, South Africa (21 November 1997). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- When in 1977, the United Nations passed the resolution inaugurating the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian people, it was asserting the recognition that injustice and gross human rights violations were being perpetrated in Palestine. In the same period, the UN took a strong stand against apartheid; and over the years, an international consensus was built, which helped to bring an end to this iniquitous system. But we know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians; without the resolution of conflicts in East Timor, the Sudan and other parts of the world.

- Address at The International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People (4 December 1997)

- Real leaders must be ready to sacrifice all for the freedom of their people.

- Nelson Madenla on leadership, Chief Albert Luthuli Centenary celebrations, Kwadukuza, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa (25 April 1998). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

Our March to Freedom is Irreversible (1990)

- Friends, Comrades and fellow South Africans. I greet you all in the name of peace, democracy and freedom for all. I stand here before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today. I therefore place the remaining years of my life in your hands.

- The majority of South Africans, black and white, recognize that apartheid has no future. It has to be ended by our own decisive mass action in order to build peace and security. The mass campaign of defiance and other actions of our organization and people can only culminate in the establishment of democracy.

- There must be an end to white monopoly on political power, and a fundamental restructuring of our political and economic systems to ensure that the inequalities of apartheid are addressed and our society thoroughly democratized.

- Our march to freedom is irreversible. We must not allow fear to stand in our way. Universal suffrage on a common voters' roll in a united, democratic and non-racial South Africa is the only way to peace and racial harmony.

Speech at a Rally in Cuba (1991)

Speech at a rally in Cuba marking the 32nd anniversary of the Cuban Revolution (26 July 1991)

- We have long wanted to visit your country and express the many feelings that we have about the Cuban revolution, about the role of Cuba in Africa, southern Africa, and the world. The Cuban people hold a special place in the hearts of the people of Africa. The Cuban internationalists have made a contribution to African independence, freedom, and justice, unparalleled for its principled and selfless character.

- We admire the achievements of the Cuban revolution in the sphere of social welfare. We note the transformation from a country of imposed backwardness to universal literacy. We acknowledge your advances in the fields of health, education, and science.

- We too are also inspired by the life and example of Jose Marti, who is not only a Cuban and Latin American hero but justly honoured by all who struggle to be free.

- We also honour the great Che Guevara, whose revolutionary exploits, including on our own continent, were too powerful for any prison censors to hide from us. The life of Che is an inspiration to all human beings who cherish freedom. We will always honour his memory.

- I must say that when we wanted to take up arms we approached numerous Western governments for assistance and we were never able to see any but the most junior ministers. When we visited Cuba we were received by the highest officials and were immediately offered whatever we wanted and needed. That was our earliest experience with Cuban internationalism.

- Long live the Cuban revolution! Long live Comrade Fidel Castro!

Speech at the Zionist Christian Church Easter Conference (1992)

- May Peace be with you! We have joined you this Easter in an act of solidarity, and in an act of worship. We have come, like all the other pilgrims, to join in an act of renewal and rededication. The festival of Easter, which is so closely linked with the festival of the Passover, marks the rebirth of the resurrected Messiah, who without arms, without soldiers, without police and covert special forces, without hit squads or bands of vigilantes, overcame the mightiest state during his time. This great festival of rejoicing marks the victory of the forces of life over death, of hope over despair. We pray with you for the blessings of peace! We pray with you for the blessings of love! We pray with you for the blessings of freedom!”

- At his speech in Moria, on 20 April 1992.

- Yes! We affirm it and we shall proclaim it from the mountaintops, that all people – be they black or white, be they brown or yellow, be they rich or poor, be they wise or fools, are created in the image of the Creator and are his children! Those who dare to cast out from the human family people of a darker hue with their racism! Those who exclude from the sight of God's grace, people who profess another faith with their religious intolerance! Those who wish to keep their fellow countrymen away from God's bounty with forced removals! Those who have driven away from the altar of God people whom He has chosen to make different, commit an ugly sin! The sin called Apartheid.

- Also quoted in Nelson Mandela: from freedom to the future: tributes and speeches' (2003), edited by Kader Asmal & David Chidester. Jonathan Ball, p. 332

Nobel Prize acceptance speech (1993)

- Together, we join two distinguished South Africans, the late Chief Albert Lutuli and His Grace Archbishop Desmond Tutu, to whose seminal contributions to the peaceful struggle against the evil system of apartheid you paid well-deserved tribute by awarding them the Nobel Peace Prize. It will not be presumptuous of us if we also add, among our predecessors, the name of another outstanding Nobel Peace Prize winner, the late Rev Martin Luther King Jr. He, too, grappled with and died in the effort to make a contribution to the just solution of the same great issues of the day which we have had to face as South Africans.We speak here of the challenge of the dichotomies of war and peace, violence and non-violence, racism and human dignity, oppression and repression and liberty and human rights, poverty and freedom from want.

- We stand here today as nothing more than a representative of the millions of our people who dared to rise up against a social system whose very essence is war, violence, racism, oppression, repression and the impoverishment of an entire people.

- I am also here today as a representative of the millions of people across the globe, the anti-apartheid movement, the governments and organisations that joined with us, not to fight against South Africa as a country or any of its peoples, but to oppose an inhuman system and sue for a speedy end to the apartheid crime against humanity.

These countless human beings, both inside and outside our country, had the nobility of spirit to stand in the path of tyranny and injustice, without seeking selfish gain. They recognised that an injury to one is an injury to all and therefore acted together in defense of justice and a common human decency.

- Because of their courage and persistence for many years, we can, today, even set the dates when all humanity will join together to celebrate one of the outstanding human victories of our century.

When that moment comes, we shall, together, rejoice in a common victory over racism, apartheid and white minority rule.

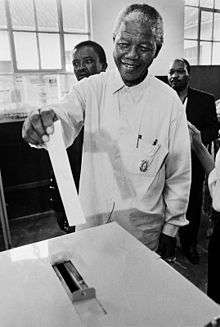

Victory speech (1994)

- Announcing the ANC election victory, Johannesburg (2 May 1994)

- My fellow South Africans — the people of South Africa:

This is indeed a joyous night. Although not yet final, we have received the provisional results of the election, and are delighted by the overwhelming support for the African National Congress.

To all those in the African National Congress and the democratic movement who worked so hard these last few days and through these many decades, I thank you and honour you. To the people of South Africa and the world who are watching: this a joyous night for the human spirit. This is your victory too. You helped end apartheid, you stood with us through the transition.

- I watched, along with all of you, as the tens of thousands of our people stood patiently in long queues for many hours. Some sleeping on the open ground overnight waiting to cast this momentous vote.

- This is one of the most important moments in the life of our country. I stand here before you filled with deep pride and joy: — pride in the ordinary, humble people of this country. You have shown such a calm, patient determination to reclaim this country as your own, - and joy that we can loudly proclaim from the rooftops — free at last!

- Tomorrow, the entire ANC leadership and I will be back at our desks. We are rolling up our sleeves to begin tackling the problems our country faces. We ask you all to join us — go back to your jobs in the morning. Let's get South Africa working.

For we must, together and without delay, begin to build a better life for all South Africans. This means creating jobs building houses, providing education and bringing peace and security for all.

- The calm and tolerant atmosphere that prevailed during the elections depicts the type of South Africa we can build. It set the tone for the future. We might have our differences, but we are one people with a common destiny in our rich variety of culture, race and tradition.

People have voted for the party of their choice and we respect that. This is democracy.

I hold out a hand of friendship to the leaders of all parties and their members, and ask all of them to join us in working together to tackle the problems we face as a nation. An ANC government will serve all the people of South Africa, not just ANC members.

- Now is the time for celebration, for South Africans to join together to celebrate the birth of democracy. I raise a glass to you all for working so hard to achieve what can only be called a small miracle. Let our celebrations be in keeping with the mood set in the elections, peaceful, respectful and disciplined, showing we are a people ready to assume the responsibilities of government.

I promise that I will do my best to be worthy of the faith and confidence you have placed in me and my organisation, the African National Congress. Let us build the future together, and toast a better life for all South Africans.

Inaugural speech (1994)

- Today we are entering a new era for our country and its people. Today we celebrate not the victory of a party, but a victory for all the people of South Africa.

Our country has arrived at a decision. Among all the parties that contested the elections, the overwhelming majority of South Africans have mandated the African National Congress to lead our country into the future. The South Africa we have struggled for, in which all our people, be they African, Coloured, Indian or White, regard themselves as citizens of one nation is at hand.

- The names of those who were incarcerated on Robben Island is a roll call of resistance fighters and democrats spanning over three centuries. If indeed this is a Cape of Good Hope, that hope owes much to the spirit of that legion of fighters and others of their calibre.

- In 1980s the African National Congress was still setting the pace, being the first major political formation in South Africa to commit itself firmly to a Bill of Rights, which we published in November 1990. These milestones give concrete expression to what South Africa can become. They speak of a constitutional, democratic, political order in which, regardless of colour, gender, religion, political opinion or sexual orientation, the law will provide for the equal protection of all citizens.

They project a democracy in which the government, whomever that government may be, will be bound by a higher set of rules, embodied in a constitution, and will not be able govern the country as it pleases.

- The people of South Africa have spoken in these elections. They want change! And change is what they will get. Our plan is to create jobs, promote peace and reconciliation, and to guarantee freedom for all South Africans.

Inaugural celebration address (1994)

- Your Majesties, Your Highnesses, Distinguished Guests, Comrades and Friends. Today, all of us do, by our presence here, and by our celebrations in other parts of our country and the world, confer glory and hope to newborn liberty. Out of the experience of an extraordinary human disaster that lasted too long, must be born a society of which all humanity will be proud.

- Our daily deeds as ordinary South Africans must produce an actual South African reality that will reinforce humanity's belief in justice, strengthen its confidence in the nobility of the human soul and sustain all our hopes for a glorious life for all.

All this we owe both to ourselves and to the peoples of the world who are so well represented here today.

- We thank all our distinguished international guests for having come to take possession with the people of our country of what is, after all, a common victory for justice, for peace, for human dignity. We trust that you will continue to stand by us as we tackle the challenges of building peace, prosperity, non-sexism, non-racialism and democracy.

- The time for the healing of the wounds has come.

The moment to bridge the chasms that divide us has come.

The time to build is upon us.

- We succeeded to take our last steps to freedom in conditions of relative peace. We commit ourselves to the construction of a complete, just and lasting peace.

We have triumphed in the effort to implant hope in the breasts of the millions of our people. We enter into a covenant that we shall build the society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity — a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.

- We dedicate this day to all the heroes and heroines in this country and the rest of the world who sacrificed in many ways and surrendered their lives so that we could be free.

Their dreams have become reality. Freedom is their reward.

- We are both humbled and elevated by the honour and privilege that you, the people of South Africa, have bestowed on us, as the first President of a united, democratic, non-racial and non-sexist government.

We understand it still that there is no easy road to freedom

We know it well that none of us acting alone can achieve success.

We must therefore act together as a united people, for national reconciliation, for nation building, for the birth of a new world.

Let there be justice for all.

Let there be peace for all.

- Never, never and never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another and suffer the indignity of being the skunk of the world.

Let freedom reign!

The sun shall never set on so glorious a human achievement!

God bless Africa!

Speech at the Zionist Christian Church Easter Conference (1994)

- We bow our heads in worship on this day and give thanks to the Almighty for the bounty He has bestowed upon us over the past year. We raise our voices in holy gladness to celebrate the victory of the risen Christ over the terrible forces of death. Easter is a joyful festival! It is a celebration because it is indeed a festival of hope! Easter marks the renewal of life! The triumph of the light of truth over the darkness of falsehood! Easter is a festival of human solidarity, because it celebrates the fulfilment of the Good News! The Good News borne by our risen Messiah who chose not one race, who chose not one country, who chose not one language, who chose not one tribe, who chose all of humankind! Each Easter marks the rebirth of our faith. It marks the victory of our risen Saviour over the torture of the cross and the grave. Our Messiah, who came to us in the form of a mortal man, but who by his suffering and crucifixion attained immortality. Our Messiah, born like an outcast in a stable, and executed like criminal on the cross. Our Messiah, whose life bears testimony to the truth that there is no shame in poverty: Those who should be ashamed are they who impoverish others. Whose life testifies to the truth that there is no shame in being persecuted: Those who should be ashamed are they who persecute others. Whose life proclaims the truth that there is no shame in being conquered: Those who should be ashamed are they who conquer others. Whose life testifies to the truth that there is no shame in being dispossessed: Those who should be ashamed are they who dispossess others. Whose life testifies to the truth that there is no shame in being oppressed: Those who should be ashamed are they who oppress others.”

- At his speech in Moria, on 3 April 1994

- “Why is it that in this day and age, human beings still butcher one another simply because they dared to belong to different religions, to speak different tongues, or belong to different races? Are human beings inherently evil? What infuses individuals with the ego and ambition to so clamour for power that genocide assumes the mantle of means that justify coveted ends? These are difficult questions, which, if wrongly examined can lead one to lose faith in fellow human beings. And there is where we would go wrong. Firstly, because to lose faith in fellow humans is, as the Archbishop would correctly point out, to lose faith in God and in the purpose of life itself. Secondly, it is erroneous to attribute to the human character a universal trait it does not possess – that of being either inherently evil or inherently humane. I would venture to say that there is something inherently good in all human beings, deriving from, among other things, the attribute of social consciousness that we all possess. And, yes, there is also something inherently bad in all of us, flesh and blood as we are, with the attendant desire to perpetuate and pamper the self. From this premise arises the challenge to order our lives and mould our mores in such a way that the good in all of us takes precedence. In other words, we are not passive and hapless souls waiting for manna or the plague from on high. All of us have a role to play in shaping society.”

- At his speech in Moria, on 3 April 1994

- African National Congress (ANC Historical Documents Archive). Johannesburg, South Africa.

Long Walk to Freedom (1995)

- When a man is denied the right to live the life he believes in, he has no choice but to become an outlaw.

- No one is born hating another person because of the colour of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.

- Education is the great engine of personal development. It is through education that the daughter of a peasant can become a doctor, that the son of a mineworker can become the head of the mine, that a child of farmworkers can become the president of a great nation. It is what we make out of what we have, not what we are given, that separates one person from another.

- A good head and a good heart are always a formidable combination.

- I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. The brave man is not he who does not feel afraid, but he who conquers that fear.

- In my country we go to prison first and then become President.

- No one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens but its lowest ones.

- There is nothing like returning to a place that remains unchanged to find the ways in which you yourself have altered.

- The greatest glory in living lies not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.

- You may succeed in delaying, but never in preventing the transition of South Africa to a democracy.

- Any man that tries to rob me of my dignity will lose.

- The victory of democracy in South Africa is the common achievement of all humanity.

- The authorities liked to say that we received a balanced diet; it was indeed balanced — between the unpalatable and the inedible.

- Prison itself is a tremendous education in the need for patience and perseverance. It is above all a test of one's commitment.

- I always knew that someday I would once again feel the grass under my feet and walk in the sunshine as a free man.

- I have always believed that exercise is the key not only to physical health but to peace of mind.

- There is no easy walk to freedom anywhere, and many of us will have to pass through the valley of the shadow of death again and again before we reach the mountaintop of our desires.

- I detest racialism because I regard it as a barbaric thing, whether it comes from a black man or a white man.

- A man does not become a freedom fighter in the hope of winning awards, but when I was notified that I had won the 1993 Nobel peace prize jointly with Mr. F.W. de Klerk, I was deeply moved. The Nobel Peace Prize had a special meaning for me because of its involvement with South Africa... The award was a tribute to all South Africans, and especially to those who fought in the struggle; I would accept it on their behalf.

- I explained to the crowd that my voice was hoarse from a cold and that my physician had advised me not to attend. "I hope that you will not disclose to him that I have violated his instructions," I told them. I congratulated Mr. de Klerk for his strong showing. I thanked all those in the ANC and the democratic movement who had worked so hard for so long. Mrs. Coretta Scott King, the wife of the great freedom fighter Martin Luther King Jr., was on the podium that night, and I looked over to her as I made reference to her husband's immortal words.

"This is one of the most important moments in the life of our country. I stand here before you filled with deep pride and joy--pride in the ordinary, humble people of this country. You have shown such a calm, patient determination to reclaim this country as your own, and now the joy that we can loudly proclaim from the rooftops — Free at last! Free at last! I stand before you humbled by your courage, with a heart full of love for all of you."

- It was during those long and lonely years that my hunger for the freedom of my own people became a hunger for the freedom of all people, white and black. I knew as well as I knew anything that the oppressor must be liberated just as surely as the oppressed. A man who takes away another man's freedom is a prisoner of hatred, he is locked behind the bars of prejudice and narrow-mindedness. I am not truly free if I am taking away someone else's freedom, just as surely as I am not free when my freedom is taken from me. The oppressed and the oppressor alike are robbed of their humanity.

When I walked out of prison, that was my mission, to liberate the oppressed and the oppressor both. Some say that has now been achieved. But I know that that is not the case. The truth is that we are not yet free; we have merely achieved the freedom to be free, the right not to be oppressed. We have not taken the final step of our journey, but the first step on a longer and even more difficult road. For to be free is not merely to cast off one's chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others. The true test of our devotion to freedom is just beginning.

- I have walked that long road to freedom. I have tried not to falter; I have made missteps along the way. But I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb. I have taken a moment here to rest, to steal a view of the glorious vista that surrounds me, to look back on the distance I have come. But I can rest only for a moment, for with freedom comes responsibilities, and I dare not linger, for my long walk is not yet ended.

- If you want to make peace with your enemy, you have to work with your enemy. Then he becomes your partner.

- I am fundamentally an optimist. Whether that comes from nature or nurture, I cannot say. Part of being optimistic is keeping one's head pointed toward the sun, one's feet moving forward. There were many dark moments when my faith in humanity was sorely tested, but I would not and could not give myself up to despair. That way lays defeat and death.

The International Day Of Solidarity With The Palestinian People (1997)

- "The International Day Of Solidarity With The Palestinian People", Pretoria (4 December 1997)

- I have come to join you today to add our own voice to the universal call for Palestinian self-determination and statehood. We would be beneath our own reason for existence as government and as a nation, if the resolution of the problems of the Middle East did not feature prominently on our agenda.

- When in 1977, the United Nations passed the resolution inaugurating the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian people, it was asserting the recognition that injustice and gross human rights violations were being perpetrated in Palestine. In the same period, the UN took a strong stand against apartheid; and over the years, an international consensus was built, which helped to bring an end to this iniquitous system.

- We know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians; without the resolution of conflicts in East Timor, the Sudan and other parts of the world.

- I wish to take this opportunity to pay tribute to these Palestinian and Israeli leaders. In particular, we pay homage to the memory of Yitshak Rabin who paid the supreme sacrifice in pursuit of peace.

2000s

.jpg)

- I was called a terrorist yesterday, but when I came out of jail, many people embraced me, including my enemies, and that is what I normally tell other people who say those who are struggling for liberation in their country are terrorists. I tell them that I was also a terrorist yesterday, but, today, I am admired by the very people who said I was one.

- During his interview at Larry King Live, (16 May 2000). Available Transcript at CNN.com: President Nelson Mandela One-on-One

- Let's hope that Ken Oosterbroek will be the last person to die.

- Spoken shortly after Inkatha announced that they would participate in the 1994 elections, as quoted in The Bang-Bang Club : Snapshots from a Hidden War (2000) by Greg Marinovich and Joao Silva, p. 168

- It is never my custom to use words lightly. If twenty-seven years in prison have done anything to us, it was to use the silence of solitude to make us understand how precious words are and how real speech is in its impact on the way people live and die.

- Nelson Mandela on words, Closing address 13th International Aids Conference, Durban, South Africa (14 July 2000). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- What counts in life is not the mere fact that we have lived. It is what difference we have made to the lives of others that will determine the significance of the life we lead.

- Nelson Mandela on life, 90th Birthday celebration of Walter Sisulu, Walter Sisulu Hall, Randburg, Johannesburg, South Africa (18 May 2002). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- We tried in our simple way to lead our life in a manner that may make a difference to those of others.

- Nelson Mandela on freedom fighters, Upon Receiving the Roosevelt Freedom Award (8 June 2002). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- Those who conduct themselves with morality, integrity and consistency need not fear the forces of inhumanity and cruelty.

- Nelson Mandela on integrity, At the British Red Cross Humanity Lecture, Queen Elizabeth Conference Centre, London, England (10 July 2003). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- Education is the most powerful weapon we can use to change the world and Mindset Network is a powerful part of that world changing arsenal.

- "Lighting your way to a better future : Speech delivered by Mr N R Mandela at launch of Mindset Network," July 16, 2003 at db.nelsonmandela.org. ; Cited in: Nelson Mandela, S. K. Hatang, Sahm Venter (2012) Notes to the Future: Words of Wisdom. p. 101.

- I remember we adjourned for lunch and a friendly Afrikaner warder asked me the question, "Mandela, what do you think is going to happen to you in this case?" I said to him, "Agh, they are going to hang us." Now, I was really expecting some word of encouragement from him. And I thought he was going to say, "Agh man, that can never happen." But he became serious and then he said, "I think you are right, they are going to hang you."

- Interview segment on All Things Considered (NPR) broadcast (27 April 2004)

- When the history of our times is written, will we be remembered as the generation that turned our backs in a moment of global crisis or will it be recorded that we did the right thing?

- Nelson Mandela on Aids, 46664 Concert, Tromso, Norway (11 Jun 2005). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- You sharpen your ideas by reducing yourself to the level of the people you are with and a sense of humour and a complete relaxation, even when you’re discussing serious things, does help to mobilise friends around you. And I love that.

- Nelson Mandela on humour, From an interview with Tim Couzens, Verne Harris and Mac Maharay for Mandela: The Authorized Portrait, 2006 (13 August 2005). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- A fundamental concern for others in our individual and community lives would go a long way in making the world the better place we so passionately dreamt of.

- Nelson Mandela on selflessness, Kliptown, Soweto, South Africa (12 July 2008). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- Everyone can rise above their circumstances and achieve success if they are dedicated to and passionate about what they do.

- Nelson Mandela on determination, From a letter to Makhaya Ntini on his 100th Cricket Test (17 December 2009). Source: From Nelson Mandela By Himself: The Authorised Book of Quotations © 2010 by Nelson R. Mandela and The Nelson Mandela Foundation

- I did not enjoy the violence of boxing so much as the science of it. I was intrigued by how one moved one's body to protect oneself, how one used a strategy both to attack and retreat, how one paced oneself over a match.

- Nelson Mandela in his autobiography, as quoted by Keegan Hamilton in the Grantland blog entry "Remembering Mandela, the Boxer" (December 6, 2013)

- Like slavery and apartheid, poverty is not natural. It is man-made and it can be overcome and eradicated by the actions of human beings. And overcoming poverty is not a gesture of charity. It is an act of justice. It is the protection of a fundamental human right, the right to dignity and a decent life. While poverty persists, there is no true freedom.

- Speech for the "Make Poverty History" campaign. Trafalgar Square, London (3 February 2005).

The Sacred Warrior (2000)

- "The Sacred Warrior" — essay on Mohandas Gandhi in TIME magazine (3 January 2000)

- India is Gandhi's country of birth; South Africa his country of adoption. He was both an Indian and a South African citizen. Both countries contributed to his intellectual and moral genius, and he shaped the liberatory movements in both colonial theaters.

He is the archetypal anticolonial revolutionary. His strategy of noncooperation, his assertion that we can be dominated only if we cooperate with our dominators, and his nonviolent resistance inspired anticolonial and antiracist movements internationally in our century.

- The Gandhian influence dominated freedom struggles on the African continent right up to the 1960s because of the power it generated and the unity it forged among the apparently powerless. Nonviolence was the official stance of all major African coalitions, and the South African A.N.C. remained implacably opposed to violence for most of its existence.

- Gandhi remained committed to nonviolence; I followed the Gandhian strategy for as long as I could, but then there came a point in our struggle when the brute force of the oppressor could no longer be countered through passive resistance alone. We founded Umkhonto we Sizwe and added a military dimension to our struggle. Even then, we chose sabotage because it did not involve the loss of life, and it offered the best hope for future race relations. Militant action became part of the African agenda officially supported by the Organization of African Unity (O.A.U.) following my address to the Pan-African Freedom Movement of East and Central Africa (PAFMECA) in 1962, in which I stated, "Force is the only language the imperialists can hear, and no country became free without some sort of violence."

- Gandhi himself never ruled out violence absolutely and unreservedly. He conceded the necessity of arms in certain situations. He said, "Where choice is set between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence... I prefer to use arms in defense of honor rather than remain the vile witness of dishonor ..."

- Gandhi arrived in South Africa in 1893 at the age of 23. Within a week he collided head on with racism. His immediate response was to flee the country that so degraded people of color, but then his inner resilience overpowered him with a sense of mission, and he stayed to redeem the dignity of the racially exploited, to pave the way for the liberation of the colonized the world over and to develop a blueprint for a new social order.

He left 21 years later, a near maha atma (great soul). There is no doubt in my mind that by the time he was violently removed from our world, he had transited into that state.

He was no ordinary leader. There are those who believe he was divinely inspired, and it is difficult not to believe with them. He dared to exhort nonviolence in a time when the violence of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had exploded on us; he exhorted morality when science, technology and the capitalist order had made it redundant; he replaced self-interest with group interest without minimizing the importance of self. In fact, the interdependence of the social and the personal is at the heart of his philosophy. He seeks the simultaneous and interactive development of the moral person and the moral society.

- His philosophy of Satyagraha is both a personal and a social struggle to realize the Truth, which he identifies as God, the Absolute Morality. He seeks this Truth, not in isolation, self-centeredly, but with the people. He said, "I want to find God, and because I want to find God, I have to find God along with other people. I don't believe I can find God alone. If I did, I would be running to the Himalayas to find God in some cave there. But since I believe that nobody can find God alone, I have to work with people. I have to take them with me. Alone I can't come to Him."

- The sight of wounded and whipped Zulus, mercilessly abandoned by their British persecutors, so appalled him that he turned full circle from his admiration for all things British to celebrating the indigenous and ethnic. He resuscitated the culture of the colonized and the fullness of Indian resistance against the British; he revived Indian handicrafts and made these into an economic weapon against the colonizer in his call for swadeshi — the use of one's own and the boycott of the oppressor's products, which deprive the people of their skills and their capital.

- A great measure of world poverty today and African poverty in particular is due to the continuing dependence on foreign markets for manufactured goods, which undermines domestic production and dams up domestic skills, apart from piling up unmanageable foreign debts. Gandhi's insistence on self-sufficiency is a basic economic principle that, if followed today, could contribute significantly to alleviating Third World poverty and stimulating development.

- Gandhi rejects the Adam Smith notion of human nature as motivated by self-interest and brute needs and returns us to our spiritual dimension with its impulses for nonviolence, justice and equality.

He exposes the fallacy of the claim that everyone can be rich and successful provided they work hard. He points to the millions who work themselves to the bone and still remain hungry.

- He stepped down from his comfortable life to join the masses on their level to seek equality with them. "I can't hope to bring about economic equality... I have to reduce myself to the level of the poorest of the poor."

From his understanding of wealth and poverty came his understanding of labor and capital, which led him to the solution of trusteeship based on the belief that there is no private ownership of capital; it is given in trust for redistribution and equalization. Similarly, while recognizing differential aptitudes and talents, he holds that these are gifts from God to be used for the collective good.

He seeks an economic order, alternative to the capitalist and communist, and finds this in sarvodaya based on nonviolence (ahimsa).

He rejects Darwin's survival of the fittest, Adam Smith's laissez-faire and Karl Marx's thesis of a natural antagonism between capital and labor, and focuses on the interdependence between the two.

He believes in the human capacity to change and wages Satyagraha against the oppressor, not to destroy him but to transform him, that he cease his oppression and join the oppressed in the pursuit of Truth.

We in South Africa brought about our new democracy relatively peacefully on the foundations of such thinking, regardless of whether we were directly influenced by Gandhi or not.

- As we find ourselves in jobless economies, societies in which small minorities consume while the masses starve, we find ourselves forced to rethink the rationale of our current globalization and to ponder the Gandhian alternative.

At a time when Freud was liberating sex, Gandhi was reining it in; when Marx was pitting worker against capitalist, Gandhi was reconciling them; when the dominant European thought had dropped God and soul out of the social reckoning, he was centralizing society in God and soul; at a time when the colonized had ceased to think and control, he dared to think and control; and when the ideologies of the colonized had virtually disappeared, he revived them and empowered them with a potency that liberated and redeemed.

Newsweek interview (2002)

- If I am asked, by credible organizations, to mediate, I will consider that very seriously. But a situation of this nature does not need an individual, it needs an organization like the United Nations to mediate.

We must understand the seriousness of this situation. The United States has made serious mistakes in the conduct of its foreign affairs, which have had unfortunate repercussions long after the decisions were taken.

- You will notice that France, Germany, Russia, China are against this decision. It is clearly a decision that is motivated by George W. Bush's desire to please the arms and oil industries in the United States of America. If you look at those factors, you'll see that an individual like myself, a man who has lost power and influence, can never be a suitable mediator.

- Neither Bush nor Tony Blair has provided any evidence that such weapons exist. But what we know is that Israel has weapons of mass destruction. Nobody talks about that. Why should there be one standard for one country, especially because it is black, and another one for another country, Israel, that is white. … Many people say quietly, but they don't have the courage to stand up and say publicly, that when there were white secretary generals you didn't find this question of the United States and Britain going out of the United Nations. But now that you've had black secretary generals like Boutros Boutros Ghali, like Kofi Annan, they do not respect the United Nations. They have contempt for it. This is not my view, but that is what is being said by many people.

- There is one compromise and one only, and that is the United Nations. If the United States and Britain go to the United Nations and the United Nations says we have concrete evidence of the existence of these weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and we feel that we must do something about it, we would all support it. … There is no doubt that the United States now feels that they are the only superpower in the world and they can do what they like. And of course we must consider the men and the women around the president. Gen. Colin Powell commanded the United States army in peacetime and in wartime during the Gulf war. He knows the disastrous effect of international tension and war, when innocent people are going to die, young men are going to die. He knows and he showed this after September 11 last year. He went around briefing the allies of the United States of America and asking for their support for the war in Afghanistan. Dick Cheney, Rumsfeld, they are people who are unfortunately misleading the president. Because my impression of the president is that this is a man with whom you can do business. But it is the men who around him who are dinosaurs, who do not want him to belong to the modern age.

- I really wanted to retire and rest and spend more time with my children, my grandchildren and of course with my wife. But the problems are such that for anybody with a conscience who can use whatever influence he may have to try to bring about peace, it's difficult to say no.

- On why he continues to be active in social and political issues.

Iraq War speech (2003)

- Speech at the International Women's Forum in Johannesburg (29 January 2003), prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

- It's a tragedy what is happening, what Bush is doing. All Bush wants is Iraqi oil. There is no doubt that the U.S. is behaving badly. Why are they not seeking to confiscate weapons of mass destruction from their ally Israel? This is just an excuse to get Iraq’s oil.

- Bush is now undermining the United Nations. He is acting outside it, not withstanding the fact that the United Nations was the idea of President Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. Both Bush, as well as Tony Blair, are undermining an idea which was sponsored by their predecessors. They do not care. Is it because the secretary-general of the United Nations [Ghanaian Kofi Annan] is now a black man? They never did that when secretary-generals were white.

- If there is a country that has committed unspeakable atrocities in the world, it is the United States of America. They don't care for human beings.

- What I am condemning is that one power, with a president [George W. Bush] who has no foresight, who cannot think properly, is now wanting to plunge the world into a holocaust.

Attributed

- Israel should withdraw from all the areas which it won from the Arabs in 1967, and in particular Israel should withdraw completely from the Golan Heights, from south Lebanon and from the West Bank.

- Suzanne Belling, "Mandela bears message of peace in first visit to Israel", jweekly.com, 22 October 1999

- I cannot conceive of Israel withdrawing if the Arab states do not recognize Israel, within secure borders.

- Suzanne Belling, "Mandela bears message of peace in first visit to Israel", jweekly.com, 22 October 1999

- One of the reasons I am so pleased to be in Israel is as a tribute to the enormous contribution of the Jewish community of South Africa [to South Africa]. I am so proud of them.

- Suzanne Belling, "Mandela bears message of peace in first visit to Israel", jweekly.com, 22 October 1999

Disputed

- We consider ourselves to be comrades in arms to the Palestinian Arabs in their struggle for the liberation of Palestine. There is not a single citizen in South Africa who is not ready to stand by his Palestinian brothers in their legitimate fight against the Zionist racists.

- This appears at Mathaba.net

Misattributed

- Our greatest fear is not that we are inadequate, but that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness, that frightens us. We ask ourselves, who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, handsome, talented, and fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small does not serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won't feel insecure around you. We were born to make manifest the glory of God within us. It is not just in some; it is in everyone. And, as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same. As we are liberated from our fear, our presence automatically liberates others.

- These statements have been misattributed to Mandela, as being in his inaugural speech of 10 May 1994 but this is not the case. Rather, they originate with author Marianne Williamson.

Quotes about Mandela

- Sorted alphabetically by author or source

.svg.png)

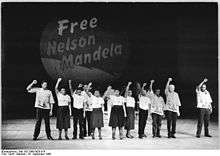

- Free Nelson Mandela!

- Anonymous political slogan, and the title of a song, "Free Nelson Mandela" (1984) by Special AKA supporting Mandela's release from prison.

- I simply don't understand why the Nobel academy gave him a peace prize or why Charlie Dimmock and Alan Titchmarsh gave him a new garden. And I don't see why he should be given a statue in Trafalgar Square, either. If we're after someone who stands up for the oppressed, what about Jesus? I feel fairly sure he never blew up a train.

- Jeremy Clarkson, in The World According to Clarkson (2005), p. 239

- There are countless remembrances in South Africa of his grace and wit, his strength, and the unconstrained speed of his forgiveness. When you take him at his word, though, you can see something else behind the beautiful character. In politics, he described himself as a strategist. He liked to make a friend, or neutralize an adversary; he liked, best of all, to transform his adversaries. For this reason his strategy, if it ever was one, was a form of the golden rule. His shrewdness about people was innocent and particular and apparently down-to-earth, and it was visible early in his life: “There is a fellow I became friendly with at Healdtown [a Methodist school], and that friendship bore fruit when I reached Johannesburg. A chap called Zachariah Molete. He was in charge of sour milk in Healdtown, and if you were friendly to him, he would give you very thick sour milk.” Mandela applied the same lesson to his jailors on Robben Island, and, in the end, to the National Party as a whole. … In truth, just as he had extended the framework of strategy to form a blueprint for humanity, Mandela pushed the idea of usefulness until it no longer resembled exploitation of things and occasions but a determination to find the universe fruitful. He took the country’s deepest and most glaring bad impulses — the constant search for individual advantage and for the chance to exploit another person, body and soul; the destructive politicization of every process; the extermination of principle by understanding that everything is strategic — and turned them inside out. He was the one man who understood South Africa, in his bones, and put its history to the only possible good use that could come of it.

- In the real world there were no freedom fighters like him. Mahatma Gandhi came closest in his insistence on transforming himself in concert with his friends and enemies. It cannot be an accident that the same intractable country produced two such great souls who drew similar conclusions and lived them out. Adversity must have its uses. … Tolstoy is a sign of what they had in common. South Africa never had a reading culture and yet, throughout its history, some books have had great power they found their way into the right hands. Mandela was not an intellectual reader, reading for the sake of reading, but he found books useful. He found novels useful. As President he would stop his driver so that he could buy some novel at the bookshop. “One book that I returned to many times was Tolstoy’s great work, War and Peace,” he wrote. “I was particularly taken with the portrait of General Kutuzov, whom everyone at the Russian court underestimated.” For Mandela, Kutuzov “made his decisions on a visceral understanding of his men and his people.” He was prepared to sacrifice the city of Moscow when it became necessary. Mandela even compared Kutuzov with King Shaka, who was also uninterested in making a stand to defend mere buildings. … On the face of it, Kutuzov is a surprising choice for Mandela’s admiration. Even for Tolstoy, “this simple, modest, and therefore truly majestic figure could not fit into that false form of the European hero, the imaginary ruler of the people, which history has invented.” Thanks to his capacity of acceptance, and in accordance with the biological needs of life within him, Kutuzov irresponsibly dozes through a council of war on the eve of battle. He despises “both knowledge and intelligence. . . . He despised them with his old age, with his experience of life.” Despite the war, he remains embedded in ordinary pursuits which are, nevertheless, incidental: “All the rest was for him only the habitual acting out of life. His conversations with the staff, his letters to Mme de Staël, which he wrote from Tarutino, his reading of novels, distribution of rewards, correspondence with Petersburg, and so on, were the same habitual acting out of and submission to life.”

Key for Mandela was the strategy of retirement and passivity that Tolstoy’s Kutuzov applied so thoroughly as to surrender to the overwhelming force of collective and unplanned life. He saw that “circumstances are sometimes stronger than we are,” resembling Lincoln, who accepted that “events have controlled me.” His principal weapons were not military. “‘Patience and time, these are my mighty warriors!’ thought Kutuzov,” who “used all his powers to keep the Russian army from useless battles.” … Patience and time were his “mighty warriors,” more powerful than the defeated South African Defense Force. Vast spiritual and political power, strategic sense and a sense of what lies beyond strategy, a deep connection and inexplicable harmony with life, were indissolubly combined in his person.

- I knew what he was going to say, because we had all seen the speech. Everybody had made comments about it. And I knew he was going to say, in effect, "Hang me if you dare to, Mr. Judge." But only when he said it... It was terribly moving. Nobody said anything. Even the judge didn't know what to say. I knew it was a moment of history. He emerged then as a great leader. … Nelson Mandela did become the symbol of the struggle for liberation in South Africa. People could identify with Nelson Mandela: Nelson Mandela the lawyer, Nelson Mandela the hero, Nelson Mandela the handsome man. But it was the response to his Rivonia Trial speech, called throughout the world the 'I am prepared to die' speech, which somersaulted him — and the African National Congress, and the need to put an end to apartheid — into the world's consciousness.

- Denis Goldberg, in interview segments on All Things Considered (NPR) broadcast (27 April 2004)

- When he was in prison I admired him for his moral strength...

Of his period in power I can see few results. Apartheid no longer exists, at least to all appearances, but no one understands what the new government in South Africa is doing.- Mengistu Haile Mariam, as quoted in Riccardo Orizio, Talk of the Devil: Encounters with Seven Dictators, (Walker and Company, 2003), pp. 148

- It has been an inspiration to the world, and it continues to be in so many regions that are divided by conflict, sectarian disputes, religious or ethnic wars, to see what happened in South Africa. The power of principle and people standing up for what's right I think continues to shine as a beacon. … The outpouring of love we have seen in recent days shows that the triumph of Nelson Mandela and this nation speaks to something very deep in the human spirit.

The yearning for justice and dignity that transcends boundaries of race and class and faith and country, that's what Nelson Mandela represents, that's what South Africa at its best can represent to the world.- President Barack Obama on a three day visit in Africa, as quoted in "Barack Obama hails Nelson Mandela as an 'inspiration' during a speech in South Africa's capital" in The Independent (29 June 2013)

- All nations have iconic historical figures on whom they draw for inspiration and strength at times of national crisis. We have the icon and we have the crisis but South Africa tragically appears to be still too disparate, divided, and confused to know how to best draw from Mandela’s example to mould a new nation. That is the sadness of Mandela’s closing years.

- Columnist William Saunderson-Meyer in the Jaundiced Eye column in The Witness: "Reality check on Mandela years" (26 July 2008)

- Mandela was a conciliator and reconciliator, not because he thought it was smart politics or would be a welcome change from the krag dadigheid of his Afrikaner predecessors. His actions were the disarmingly simple outcome of an intricate and nuanced set of personal values. Consequently, while Mandela’s opponents, including many within the ANC, might have disagreed with his decisions, they had to accord them some grudging respect. A Mandela standpoint might be unpopular, but one mostly had to admire the palpable moral logic behind it.

That is not to say that Mandela was a naïve idealist. He knew that pragmatism sometimes meant shelving morality, at least temporarily. But the generally consistent values that drove Mandela’s actions crucially helped restore faith in government by a citizenry that had been alienated by decades of government venalit y and turpitude. For example, Mandela did not pause to weigh the benefits of a complicit silence towards a powerful, oil-rich state, when the Nigerian government hanged the activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. He immediately called for the Commonwealth to suspend Nigeria, although this arguably diminished South Africa’s influence on the continent.- Columnist William Saunderson-Meyer, in "Zuma’s dangerous moral diffidence" in The Witness (3 October 2009)

- Huge crowds! The day when Nelson Mandela was duly inaugurated the first democratically elected president of South Africa... And you sat there, and you looked at the benches of the newly elected legislators, and there were all these "terrorists" — as they had been regarded by the former apartheid government. And there they were sitting. Many had been on Robben Island, in exile, many had been tortured. Many of us kept having to pinch ourselves to say, "No, man, I am dreaming."

- Archbishop Desmond Tutu on Mandela's inauguration as President, Mandela: An Audio History (Part 5)

- How can a man who committed adultery and left his wife and children be Christ? The whole world worships Nelson too much. He is only a man.

- Evelyn Mase, Mandela's first wife, as quoted by David James Smith, (2010), in Young Mandela. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 59; as something she said to journalist Fred Bridgland after Mandela's release being compared to the second coming of Christ.

- Nelson Mandela’s speech at the Johannesburg concert [July 2005] was relayed at other concerts across the globe. “While poverty persists, there is no true freedom,” he said and urged the leaders of the world “not to look away” but to “act with courage and vision”. He told the audience: “Sometimes it falls upon a generation to be great. You can be that generation. Let your greatness blossom. Of course the task will not be easy. But not to do this would be a crime against humanity against which I ask all humanity now to rise up.”

- It was no surprise that one of Nelson Mandela’s first trips outside South Africa – after he was freed – was to Havana. There, in July 1991, Mandela referred to Castro as “a source of inspiration to all freedom-loving people”. At the end of his Cuban trip, Mandela responded to American criticism about his loyalty to Castro: “We are now being advised about Cuba by people who have supported the apartheid regime these last 40 years. No honourable man or woman could ever accept advice from people who never cared for us at the most difficult times.”

Eulogy by Barack Obama

- Statements of US President Barack Obama, at First National Bank Stadium in Johannesburg, South Africa, published in "Remarks by President Obama at Memorial Service for Former South African President Nelson Mandela" (10 December 2013)

- It is hard to eulogize any man — to capture in words not just the facts and the dates that make a life, but the essential truth of a person — their private joys and sorrows; the quiet moments and unique qualities that illuminate someone’s soul. How much harder to do so for a giant of history, who moved a nation toward justice, and in the process moved billions around the world.

- Born during World War I, far from the corridors of power, a boy raised herding cattle and tutored by the elders of his Thembu tribe, Madiba would emerge as the last great liberator of the 20th century. Like Gandhi, he would lead a resistance movement — a movement that at its start had little prospect for success. Like Dr. King, he would give potent voice to the claims of the oppressed and the moral necessity of racial justice. He would endure a brutal imprisonment that began in the time of Kennedy and Khrushchev, and reached the final days of the Cold War. Emerging from prison, without the force of arms, he would — like Abraham Lincoln — hold his country together when it threatened to break apart. And like America’s Founding Fathers, he would erect a constitutional order to preserve freedom for future generations — a commitment to democracy and rule of law ratified not only by his election, but by his willingness to step down from power after only one term.

- He was not a bust made of marble; he was a man of flesh and blood — a son and a husband, a father and a friend. And that’s why we learned so much from him, and that’s why we can learn from him still. For nothing he achieved was inevitable. In the arc of his life, we see a man who earned his place in history through struggle and shrewdness, and persistence and faith. He tells us what is possible not just in the pages of history books, but in our own lives as well.

- Mandela taught us the power of action, but he also taught us the power of ideas; the importance of reason and arguments; the need to study not only those who you agree with, but also those who you don’t agree with. He understood that ideas cannot be contained by prison walls, or extinguished by a sniper’s bullet. He turned his trial into an indictment of apartheid because of his eloquence and his passion, but also because of his training as an advocate. He used decades in prison to sharpen his arguments, but also to spread his thirst for knowledge to others in the movement. And he learned the language and the customs of his oppressor so that one day he might better convey to them how their own freedom depend upon his.

- Mandela demonstrated that action and ideas are not enough. No matter how right, they must be chiseled into law and institutions. He was practical, testing his beliefs against the hard surface of circumstance and history. On core principles he was unyielding, which is why he could rebuff offers of unconditional release, reminding the Apartheid regime that “prisoners cannot enter into contracts.” But as he showed in painstaking negotiations to transfer power and draft new laws, he was not afraid to compromise for the sake of a larger goal. And because he was not only a leader of a movement but a skillful politician, the Constitution that emerged was worthy of this multiracial democracy, true to his vision of laws that protect minority as well as majority rights, and the precious freedoms of every South African.

- It took a man like Madiba to free not just the prisoner, but the jailer as well to show that you must trust others so that they may trust you; to teach that reconciliation is not a matter of ignoring a cruel past, but a means of confronting it with inclusion and generosity and truth. He changed laws, but he also changed hearts.

- The questions we face today — how to promote equality and justice; how to uphold freedom and human rights; how to end conflict and sectarian war — these things do not have easy answers. But there were no easy answers in front of that child born in World War I. Nelson Mandela reminds us that it always seems impossible until it is done. South Africa shows that is true. South Africa shows we can change, that we can choose a world defined not by our differences, but by our common hopes. We can choose a world defined not by conflict, but by peace and justice and opportunity.

- We will never see the likes of Nelson Mandela again. But let me say to the young people of Africa and the young people around the world — you, too, can make his life’s work your own. Over 30 years ago, while still a student, I learned of Nelson Mandela and the struggles taking place in this beautiful land, and it stirred something in me. It woke me up to my responsibilities to others and to myself, and it set me on an improbable journey that finds me here today. And while I will always fall short of Madiba’s example, he makes me want to be a better man. He speaks to what’s best inside us.

After this great liberator is laid to rest, and when we have returned to our cities and villages and rejoined our daily routines, let us search for his strength. Let us search for his largeness of spirit somewhere inside of ourselves. And when the night grows dark, when injustice weighs heavy on our hearts, when our best-laid plans seem beyond our reach, let us think of Madiba and the words that brought him comfort within the four walls of his cell: “It matters not how strait the gate, how charged with punishments the scroll, I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.”

What a magnificent soul it was. We will miss him deeply.

.jpg)