Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author and socialist, most famous for his utopian novel, Looking Backward, a tale set in the distant future of the year 2000. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of at least 165 "Nationalist Clubs" dedicated to the propagation of Bellamy's political ideas and working to make them a practical reality.

Quotes

- As political equality is the remedy for political tyranny, so is economic equality the only way of putting an end to the economic tyranny exercised by the few over the many through superiority of wealth. The industrial system of a nation, like its political system, should be a government of the people, by the people, for the people. Until economic equality shall give a basis to political equality, the latter is but a sham.

- Masthead, from Bellamy's newspaper The New Nation. Quoted in Charles Allan Madison, Critics and Crusaders: Political Economy and the American Quest for Freedom, Transaction Publishers, 1948.

Dr. Heidenhoff's Process (1880)

- Forgiving sins, I should have known, is not blotting them out. The blood of Christ only turns them red instead of black. It leaves them in the record. It leaves them in the memory.

- Ch. 1.

- A sense of utter loneliness—loneliness inevitable, crushing, eternal, the loneliness of existence, encompassed by the infinite void of unconsciousness—enfolded him as a pall. Life lay like an incubus on his bosom. He shuddered at the thought that death might overlook him, and deny him its refuge.

- Ch. 2.

- No girl, however coolly her blood may flow, can be pressed to a man's breast, wildly throbbing with love for her, and not experience some agitation in consequence. Whatever may be the state of her sentiments, there is a magnetism in such a contact which she cannot at once throw off. That kiss had brought her relations with Henry to a crisis. It had precipitated the necessity of some decision. She could no longer hold him off, and play with him. By that bold dash he had gained a vantage-ground, a certain masterful attitude which he had never held before. Yet, after all, I am not sure that she was not just a little afraid of him, and, moreover, that she did not like him all the better for it.

- Ch. 3.

- The most dangerous lovers women have are men of Cordis's feminine temperament. Such men, by the delicacy and sensitiveness of their own organizations, read women as easily and accurately as women read each other. They are alert to detect and interpret those smallest trifles in tone, expression, and bearing, which betray the real mood far more unmistakably than more obvious signs.

- Ch. 4.

- And, in heaven's name, who are the public enemies?...In your day governments were accustomed, on the slightest international misunderstanding, to seize upon the bodies of citizens and deliver them over by hundreds of thousands to death and mutilation, wasting their treasures the while like water; and all this oftenest for no imaginable profit to the victims.

- Ch. 6.

We have no wars now, and our governments no war powers, but in order to protect every citizen against hunger, cold, and nakedness, and provide for all his physical and mental needs, the function is assumed of directing his industry for a term of years. No, Mr. West, I am sure on reflection you will perceive that it was in your age, not in ours, that the extension of the functions of governments was extraordinary. Not even for the best ends would men now allow their governments such powers as were then used for the most maleficent.

- Ch. 6.

- But one thing it opened her eyes to, and made certain from the first instant of her new consciousness, namely, that since she loved him she could not keep her promise to marry him.

- Ch. 8.

- Why, when the world gets to understand about it I expect that two men or two women, or a man and a woman, will come in here, and say to me, 'We have quarrelled and outraged each other, we have injured our friend, our wife, our husband; we regret, we would forgive, but we cannot, because we remember. Put between us the atonement of forgetfulness, that we may love each other as of old.

- Ch. 11.

Presently, too, as I observed the wretched beings about me more closely, I perceived that they were all quite dead. Their bodies were so many living sepulchres. On each brutal brow was plainly written the hic jacet of a soul dead within.

'_(11220630093).jpg)

- The difference between the past and present selves of the same individual is so great as to make them different persons for all moral purposes. That single fact we were just speaking of—the fact that no man would care for vengeance on one who had injured him, provided he knew that all memory of the offence had been blotted utterly from his enemy's mind—proves the entire proposition. It shows that it is not the present self of his enemy that the avenger is angry with at all, but the past self. Even in the blindness of his wrath he intuitively recognizes the distinction between the two.

- Ch. 11.

Looking Backward, 2000-1887 (1888)

- In the first place, it was firmly and sincerely believed that there was no other way in which Society could get along, except the many pulled at the rope and the few rode, and not only this, but that no very radical improvement even was possible, either in the harness, the coach, the roadway, or the distribution of the toil. It had always been as it was, and it always would be so. It was a pity, but it could not be helped, and philosophy forbade wasting compassion on what was beyond remedy.

- Ch. 1.

- Human history, like all great movements, was cyclical, and returned to the point of beginning. the idea of indefinite progress in a right line was a chimera of the imagination, with no analogue in nature. The parabola of a comet was perhaps a better illustration of the career of humanity. Tending upward and sunward from the aphelion of barbarism, the race attained the perihelion of civilization only to plunge downward once more to its nether goal in the regions of chaos.

- Ch. 1.

- What we did see was that industrially the country was in a very queer way. The relation between the workingman and the employer, between labor and capital, appeared in some unaccountable manner to have become dislocated. The working classes had quite suddenly and very generally become infected with a profound discontent with their condition, and an idea that it could be greatly bettered if they only knew how to go about it. On every side, with one accord, they preferred demands for higher pay, shorter hours, better dwellings, better educational advantages, and a share in the refinements and luxuries of life, demands which it was impossible to see the way to granting unless the world were to become a great deal richer than it then was.

- Ch. 1.

- It was no doubt the common opinion of thoughtful men that society was approaching a critical period which might result in great changes. The labor troubles, their causes, course, and cure, took lead of all other topics in the public prints, and in serious conversation.

- Ch. 1.

- The nervous tension of the public mind could not have been more strikingly illustrated than it was by the alarm resulting from the talk of a small band of men who called themselves anarchists, and proposed to terrify the American people into adopting their ideas by threats of violence, as if a mighty nation which had but just put down a rebellion of half its own numbers, in order to maintain its political system, were likely to adopt a new social system out of fear.

- Ch. 1.

- As one of the wealthy, with a large stake in the existing order of things, I naturally shared the apprehensions of my class. The particular grievance I had against the working classes at the time of which I write, on account of the effect of their strikes in postponing my wedded bliss, no doubt lent a special animosity to my feeling toward them.

- Ch. 1.

- The cities of that period were rather shabby affairs. If you had the taste to make them splendid, which I would not be so rude as to question, the general poverty resulting from your extraordinary industrial system would not have given you the means. Moreover, the excessive individualism which then prevailed was inconsistent with much public spirit. What little wealth you had seems almost wholly to have been lavished in private luxury. Nowadays, on the contrary, there is no destination of the surplus wealth so popular as the adornment of the city, which all enjoy in equal degree.

- Ch. 4.

- The industry and commerce of the country, ceasing to be conducted by a set of irresponsible corporations and syndicates of private persons at their caprice and for their profit, were entrusted to a single syndicate representing the people, to be conducted in the common interest for the common profit. The nation, that is to say, organized as the one great business corporation in which all other corporations were absorbed; it became the one capitalist in the place of all other capitalists, the sole employer, the final monopoly in which all previous and lesser monopolies were swallowed up, a monopoly in the profits and economies of which all citizens shared.

- Ch. 5.

- Hold the period of youth sacred to education, and the period of maturity, when the physical forces begin to flag, equally sacred to ease and agreeable relaxation.

- Ch. 6.

- The organization of society with you was such that officials were under a constant temptation to misuse their power for the private profit of themselves or others. Under such circumstances it seems almost strange that you dared entrust them with any of your affairs. Nowadays, on the contrary, society is so constituted that there is absolutely no way in which an official, however ill-disposed, could possibly make any profit for himself or any one else by a misuse of his power. Let him be as bad an official as you please, he cannot be a corrupt one. There is no motive to be. The social system no longer offers a premium on dishonesty.

- Ch. 6.

- We leave the question whether a man shall be a brain or hand worker entirely to him to settle. At the end of the term of three years as a common laborer, which every man must serve, it is for him to choose, in accordance to his natural tastes, whether he will fit himself for an art or profession, or be a farmer or mechanic. If he feels that he can do better work with his brains than his muscles, he finds every facility provided for testing the reality of his supposed bent, of cultivating it, and if fit of pursuing it as his avocation. The schools of technology, of medicine, of art, of music, of histrionics, and of higher liberal learning are always open to aspirants without condition.

- Ch. 7.

- Buying and selling is essentially antisocial.

- Ch. 9.

- The nation guarantees the nurture, education, and comfortable maintenance of every citizen from the cradle to the grave.

- Ch. 9.

- When you come to analyze the love of money which was the general impulse to effort in your day, you find that the dread of want and desire of luxury was but one of several motives which the pursuit of money represented; the others, and with many the more influential, being desire of power, of social position, and reputation for ability and success.

- Ch. 9.

- Badly off as the men... were in your day, they were more fortunate than their mothers and wives.

- Ch. 11.

- [I]f we could have devised an arrangement for providing everybody with music in their homes, perfect in quality, unlimited in quantity, suited to every mood, and beginning and ceasing at will, we should have considered the limit of human felicity already attained, and ceased to strive for further improvements.

- Ch. 11.

- An American credit card... is just as good in Europe as American gold used to be.

- Ch. 13.

- Equal wealth and equal opportunities of culture... have simply made us all members of one class.

- Ch. 14.

- If bread is the first necessity of life, recreation is a close second.

- Ch. 18.

- In your day fully nineteen twentieths of the crime, using the word broadly to include all sorts of misdemeanors, resulted from the inequality in the possessions of individuals; want tempted the poor, lust of greater gains, or the desire to preserve former gains, tempted the well-to-do. Directly or indirectly, the desire for money, which then meant every good thing, was the motive of all this crime, the taproot of a vast poison growth, which the machinery of law, courts, and police could barely prevent from choking your civilization outright.

- Ch. 19

- When we made the nation the sole trustee of the wealth of the people, and guaranteed to all abundant maintenance, on the one hand abolishing want, and on the other checking the accumulation of riches, we cut this root, and the poison tree that overshadowed your society withered, like Jonah's gourd, in a day. As for the comparatively small class of violent crimes against persons, unconnected with any idea of gain, they were almost wholly confined, even in your day, to the ignorant and bestial; and in these days, when education and good manners are not the monopoly of a few, but universal, such atrocities are scarcely ever heard of.

- Ch. 19

- We do without the lawyers, certainly... It would not seem reasonable to us, in a case where the only interest of the nation is to find out the truth, that persons should take part in the proceedings who had an acknowledged motive to color it. But who defends the accused? If he is a criminal he needs no defense, for he pleads guilty in most instances. The plea of the accused is not a mere formality with us, as with you. It is usually the end of the case.

- Ch. 19

- If he denies his guilt, must still be tried. But trials are few, for in most cases the guilty man pleads guilty. When he makes a false plea and is clearly proved guilty, his penalty is doubled. Falsehood is, however, so despised among us that few offenders would lie to save themselves... If lying has gone out of fashion, this is indeed the 'new heavens and the new earth wherein dwelleth righteousness,' which the prophet foretold.

- Ch. 19

- There is neither private property, beyond personal belongings, now, nor buying and selling, and therefore the occasion of nearly all the legislation formerly necessary has passed away. Formerly, society was a pyramid poised on its apex. All the gravitations of human nature were constantly tending to topple it over, and it could be maintained upright, or rather upwrong (if you will pardon the feeble witticism), by an elaborate system of constantly renewed props and buttresses and guy-ropes in the form of laws. A central Congress and forty state legislatures, turning out some twenty thousand laws a year, could not make new props fast enough to take the place of those which were constantly breaking down or becoming ineffectual through some shifting of the strain. Now society rests on its base, and is in as little need of artificial supports as the everlasting hills.

- Ch. 19

- Whatever her sorrow had once been, for nearly a century she had ceased to weep, and, my sudden passion spent, my own tears dried away. I had loved her very dearly in my other life, but it was a hundred years ago! I do not know but some may find in this confession evidence of lack of feeling, but I think, perhaps, that none can have had an experience sufficiently like mine to enable them to judge me.

- Ch. 20

- You will see...many very important differences between our methods of education and yours, but the main difference is that nowadays all persons equally have those opportunities of higher education which in your day only an infinitesimal portion of the population enjoyed. We should think we had gained nothing worth speaking of, in equalizing the physical comfort of men, without this educational equality....

- Ch. 21.

- If it took half the revenue of the nation, nobody would grudge it, nor even if it took it all save a bare pittance. But in truth the expense of educating ten thousand youth is not ten nor five times that of educating one thousand. The principle which makes all operations on a large scale proportionally cheaper than on a small scale holds as to education also.

- Ch. 21.

- The actual expense of your colleges appears to have been very low, and would have been far lower if their patronage had been greater. The higher education nowadays is as cheap as the lower, as all grades of teachers, like all other workers, receive the same support. We have simply added to the common school system of compulsory education, in vogue in Massachusetts a hundred years ago, a half dozen higher grades, carrying the youth to the age of twenty-one and giving him what you used to call the education of a gentleman, instead of turning him loose at fourteen or fifteen with no mental equipment beyond reading, writing, and the multiplication table.

- Ch. 21.

- The greater efficiency which education gives to all sorts of labor, except the rudest, makes up in a short period for the time lost in acquiring it.

- Ch. 21.

- Manual labor meant association with a rude, coarse, and ignorant class of people. There is no such class now.

- Ch. 21.

- No single thing is so important to every man as to have for neighbors intelligent, companionable persons. There is nothing, therefore, which the nation can do for him that will enhance so much his own happiness as to educate his neighbors.

- Ch. 21.

- To educate some to the highest degree, and leave the mass wholly uncultivated, as you did, made the gap between them almost like that between different natural species, which have no means of communication. What could be more inhuman than this consequence of a partial enjoyment of education!

- Ch. 21.

- In your day, riches debauched one class with idleness of mind and body, while poverty sapped the vitality of the masses by overwork, bad food, and pestilent homes. The labor required of children, and the burdens laid on women, enfeebled the very springs of life. Instead of these maleficent circumstances, all now enjoy the most favorable conditions of physical life; the young are carefully nurtured and studiously cared for; the labor which is required of all is limited to the period of greatest bodily vigor, and is never excessive; care for one's self and one's family, anxiety as to livelihood, the strain of a ceaseless battle for life—all these influences, which once did so much to wreck the minds and bodies of men and women, are known no more... Insanity, for instance, which in the nineteenth century was so terribly common a product of your insane mode of life, has almost disappeared, with its alternative, suicide.

- Ch. 21.

- Your system was liable to periodical convulsions...business crises at intervals of five to ten years, which wrecked the industries of the nation.

- Ch. 22.

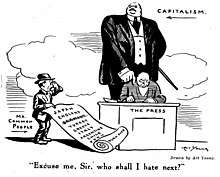

- The next of the great wastes was that from competition. The field of industry was a battlefield as wide as the world, in which the workers wasted, in assailing one another, energies which, if expended in concerted effort, as to-day, would have enriched all. As for mercy or quarter in this warfare, there was absolutely no suggestion of it. To deliberately enter a field of business and destroy the enterprises of those who had occupied it previously, in order to plant one's own enterprise on their ruins, was an achievement which never failed to command popular admiration. Nor is there any stretch of fancy in comparing this sort of struggle with actual warfare, so far as concerns the mental agony and physical suffering which attended the struggle, and the misery which overwhelmed the defeated and those dependent on them. Now nothing about your age is, at first sight, more astounding to a man of modern times than the fact that men engaged in the same industry, instead of fraternizing as comrades and co-laborers to a common end, should have regarded each other as rivals and enemies to be throttled and overthrown. This certainly seems like sheer madness, a scene from bedlam.

- Ch. 22.

- Your contemporaries, with their mutual throat-cutting, knew very well what they were at. The producers of the nineteenth century were not, like ours, working together for the maintenance e of the community, but each solely for his own maintenance at the expense of the community. If, in working to this end, he at the same time increased the aggregate wealth, that was merely incidental. It was just as feasible and as common to increase one's private hoard by practices injurious to the general welfare. One's worst enemies were necessarily those of his own trade, for, under your plan of making private profit the motive of production, a scarcity of the article he produced was what each particular producer desired.

- Ch. 22

- Their system of unorganized and antagonistic industries was as absurd economically as it was morally abominable. Selfishness was their only science, and in industrial production selfishness is suicide. Competition, which is the instinct of selfishness, is another word for dissipation of energy, while combination is the secret of efficient production; and not till the idea of increasing the individual hoard gives place to the idea of increasing the common stock can industrial combination be realized, and the acquisition of wealth really begin. Even if the principle of share and share alike for all men were not the only humane and rational basis for a society, we should still enforce it as economically expedient, seeing that until the disintegrating influence of self-seeking is suppressed no true concert of industry is possible.'

- Ch. 22.

- My friends, if you would see men again the beasts of prey they seemed in the nineteenth century, all you have to do is to restore the old social and industrial system, which taught them to view their natural prey in their fellow-men, and find their gain in the loss of others. No doubt it seems to you that no necessity, however dire, would have tempted you to subsist on what superior skill or strength enabled you to wrest from others equally needy.

- Ch. 26.

- Even the ministers of religion were not exempt from this cruel necessity. While they warned their flocks against the love of money, regard for their families compelled them to keep an outlook for the pecuniary prizes of their calling. Poor fellows, theirs was indeed a trying business, preaching to men a generosity and unselfishness which they and everybody knew would, in the existing state of the world, reduce to poverty those who should practice them, laying down laws of conduct which the law of self-preservation compelled men to break.

- Ch. 26.

- Stores! stores! stores! miles of stores! ten thousand stores to distribute the goods needed by this one city, which in my dream had been supplied with all things from a single warehouse, as they were ordered through one great store in every quarter, where the buyer, without waste of time or labor, found under one roof the world's assortment in whatever line he desired. There the labor of distribution had been so slight as to add but a scarcely perceptible fraction to the cost of commodities to the user. The cost of production was virtually all he paid. But here the mere distribution of the goods, their handling alone, added a fourth, a third, a half and more, to the cost. All these ten thousand plants must be paid for, their rent, their staffs of superintendence, their platoons of salesmen, their ten thousand sets of accountants, jobbers, and business dependents, with all they spent in advertising themselves and fighting one another, and the consumers must do the paying. What a famous process for beggaring a nation!

- Ch. 28.

- Could they be reasoning beings, who did not see the folly which, when the product is made and ready for use, wastes so much of it in getting it to the user? If people eat with a spoon that leaks half its contents between bowl and lip, are they not likely to go hungry?

- Ch. 28.

- Presently, too, as I observed the wretched beings about me more closely, I perceived that they were all quite dead. Their bodies were so many living sepulchres. On each brutal brow was plainly written the hic jacet of a soul dead within.

- Ch. 28.

- As I looked, horror struck, from one death's head to another, I was affected by a singular hallucination. Like a wavering translucent spirit face superimposed upon each of these brutish masks I saw the ideal, the possible face that would have been the actual if mind and soul had lived.

- Ch. 28.

- I was moved with contrition as with a strong agony, for I had been one of those who had endured that these things should be. Therefore now I found upon my garments the blood of this great multitude of strangled souls of my brothers. The voice of their blood cried out against me from the ground. Every stone of the reeking pavements, every brick of the pestilential rookeries, found a tongue and called after me as I fled: What hast thou done with thy brother Abel?

- Ch. 28.

- Do you not know that close to your doors a great multitude of men and women, flesh of your flesh, live lives that are one agony from birth to death? Listen! their dwellings are so near that if you hush your laughter you will hear their grievous voices, the piteous crying of the little ones that suckle poverty, the hoarse curses of men sodden in misery turned half-way back to brutes, the chaffering of an army of women selling themselves for bread. With what have you stopped your ears that you do not hear these doleful sounds?

- Ch. 28.

- The folly of men, not their hard-heartedness, was the great cause of the world's poverty. It was not the crime of man, nor of any class of men, that made the race so miserable, but a hideous, ghastly mistake, a colossal world-darkening blunder.

- Ch. 28.

- On no other stage are the scenes shifted with a swiftness so like magic as on the great stage of history when once the hour strikes.

- Author's postscript.

- Looking Backward was written in the belief that the Golden Age lies before us and not behind us.

- Author's postscript.

About Bellamy

- "Progress" is for the convinced ochlocrats a consoling Utopia of madly increased comfort and technicism. This charming but dull vision was always the pseudoreligious consolation of millions of ecstatic believers in ochlocracy and in the relative perfection and wisdom of Mr. and Mrs. Averageman. Utopias in general are surrogates for heaven; they give a meager solace to the individual that his sufferings and endeavors may enable future generations to enter the chiliastic paradise. Communism works in a similar way. Its millennium is almost the same as that of ochlocracy. The Millennium of Lenin, the Millennium of Bellamy, the Millennium as represented in H. G. Wells's, "Of Things to Come," the Millennium of Adolf Hitler and Henry Ford — they are all basically the same; they often differ in their means to attain it but they all agree in the point of technical perfection and the classless or at least totally homogeneous society without grudge or envy.

- Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn writing under the pen name Francis Stewart Campbell (1943), Menace of the Herd, or, Procrustes at Large, Milwaukee, WI: The Bruce Publishing Company, pp. 35-36

- It was the genius of Edward Bellamy that he took Utopia out of the region of hazy dreamland and made it a concrete program for the actual modern world. A reviewer of Looking Backward wrote: "Men read the Republic or the Utopia with a sigh of regret. They read Bellamy with a thrill of hope." His picture of a better world, and the hope and expectation of its fulfillment, were transmitted through the years until those who looked to him as the source of their initial inspiration constituted an important part of the army of social progress.

- Arthur Ernest Morgan, Edward Bellamy. Columbia University Press, 1944.

- Mr. Bellamy's ideas of life are curiously limited; he has no idea beyond existence in a great city; his dwelling of man in the future is Boston (U.S.A.) beautified. In one passage, indeed, he mentions villages, but with unconscious simplicity shows that they do not come into his scheme of economical equality, but are mere servants of the great centres of civilisation. This seems strange to some of us, who cannot help thinking that our experience ought to have taught us that such aggregations of population afford the worst possible form of dwelling-place, whatever the second-worst might be. In short, a machine-life is the best which Mr. Bellamy can imagine for us on all sides; it is not to be wondered at then this his only idea of making labour tolerable is to decrease the amount of it by means of fresh and ever fresh developments of machinery.

- William Morris, "Bellamy's Looking Backward", Commonweal, 21st June 1889.

- From boyhood—when I was an ardent admirer of Robert Owen—I have been interested in socialism, but reluctantly came to the conclusion that it was impracticable, and also to some extent repugnant to my ideas of individual liberty and home privacy. But Mr. Bellamy has completely altered my views on this matter. He seems to me to have shown that real, not merely delusive liberty, together with full scope for individualism and complete home privacy, is compatible with the most thorough industrial socialism—and henceforth I am heart and soul with him.

- Alfred Russel Wallace, The Wonderful Century: Its Successes and Its Failures. Toronto : G.N. Morang, 1898.

See also

External links

- Wikipedia page about Looking Backward: 2000–1887